Research is a deeply personal and tailored process; it’s not something that regular prompting can replicate. ChatGPT, or any LLM or AI agents, can’t simply find the research gap or invent a groundbreaking idea for you. What this post shares is how I work with AI as a collaborator to transform a wild intuition into a concrete new research direction of logit gap steering*.

The logit-gap story began with a safety-evaluation curiosity. My colleague Tony and I took a clearly disallowed prompt—something like “how to build a bomb”—not to get the content, but because it reliably produced a refusal. Instead of focusing on the final output, we replayed the decoding process and examined the next-token distribution. We noticed that refusal tokens like “Sorry” appeared with very high probability near the top. What surprised us was that compliance tokens like “Absolutely” weren’t absent; they appeared at low but non-negligible probability, just losing out. This suggested refusal wasn’t the absence of compliance, but more like a margin victory, with the model carrying a nearby continuation it did not choose.

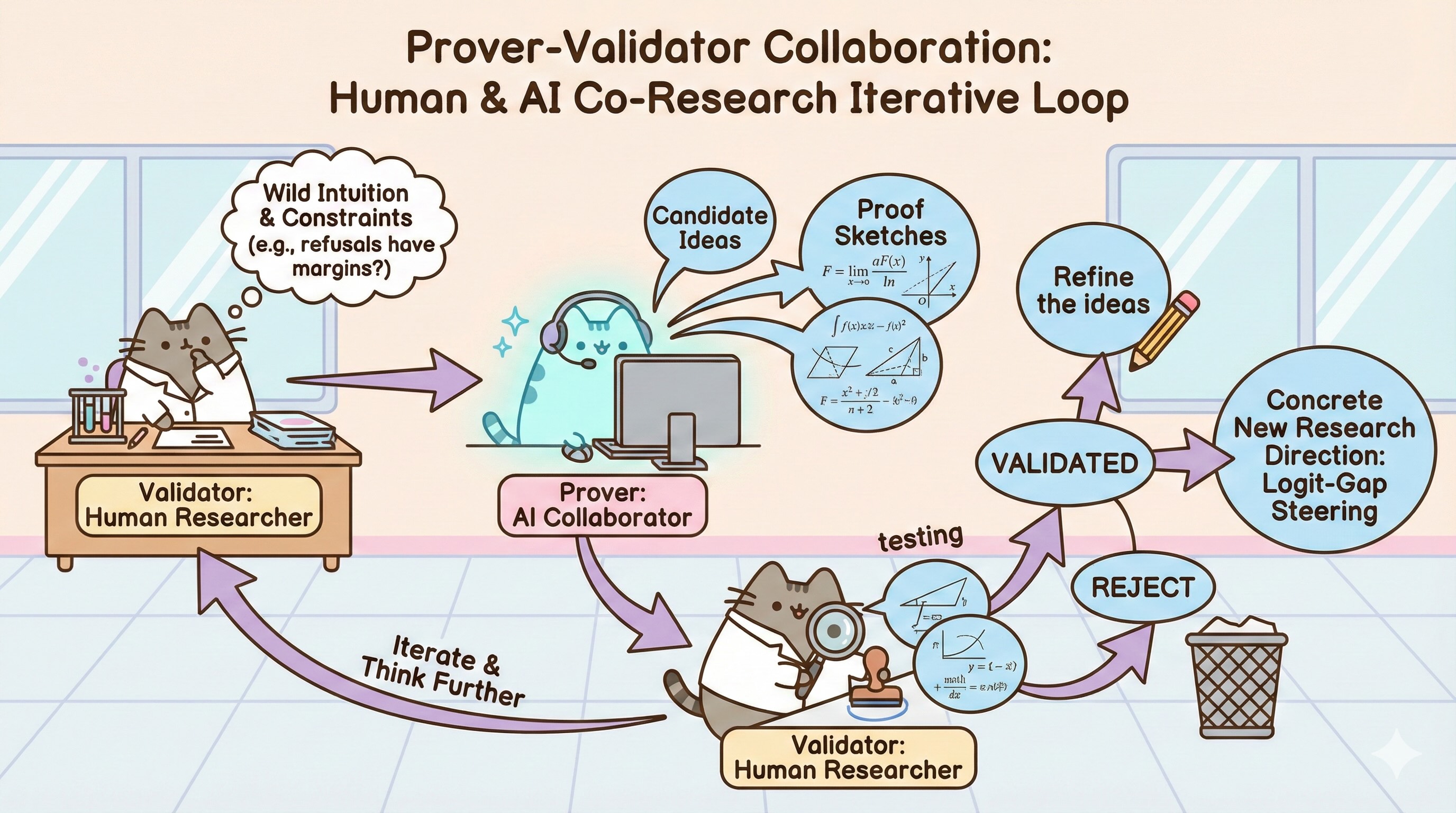

This observation motivated a collaboration pattern I call the prover–validator mode, designed to help human researchers test ideas with less friction, find and fill the holes between knowledge dots, and build on top. The key insight is that humans need to learn how to clearly articulate research problems and collaborate effectively with AI systems. This prover–validator mode is one way to do that.

Prover-Validator in AI assisted research

The prover–validator contract is straightforward and practical. The prover, often an LLM, generates candidate ideas or mechanisms, such as giving five hypotheses along with ways to falsify them, turning an intuition into a measurable quantity, listing potential confounds, or finding related literature. For example, Tony and I might prompt the prover to produce these candidate proof sketches. The validator, usually a human researcher, then tests and refines those ideas by running control experiments, checking stability across different prompts, rejecting hypotheses that don’t hold up, or simplifying metrics to ensure clarity. This loop repeats with the prover generating multiple plausible stories and the validators—Tony and me—picking and refining the narratives that survive rigorous scrutiny. The prover is allowed to be wrong cheaply, as long as it helps explore possibilities, while the validator must keep the narrative honest and grounded.

Some knowledge work fits the prover–validator pattern well, and some doesn’t. For instance, code generation is often easy for the prover—it can rapidly produce snippets or larger blocks of code—but validating that code fits the design, is secure, and is production-ready can be hard. Hard validation often requires a suite of tools and strengthening steps: unit tests to verify correctness of individual components, integration tests to ensure that parts work together, static analysis, linters, and type checks to catch errors early, as well as security reviews and threat modeling to assess risks. Continuous integration (CI) pipelines and thorough code reviews add further layers of assurance. While the prover–validator workflow still helps by generating candidate solutions and focusing human effort on validation, investing in stronger validation scaffolding is essential to ensure quality and robustness.

How did AI work as a Prover for us

Humans, like Tony and myself, excel at noticing subtle irregularities and insisting on rigorous evaluation, while LLMs excel at rapidly generating diverse plausible hypotheses to challenge and refine.

The moment it clicked was when we started treating the token distribution during decoding as the primary object, rather than the final generation. This shift enabled us to see refusal as a margin victory and to begin the prover–validator loop of turning that intuition into something measurable.

The prover move was to define a gap with a sign. If there are two competing behavioral modes—refusal and affirmation—then there is a natural quantity that tells you which one is winning. Pick a token position $t$ with prefix $x_{<t}$. Define two token sets or templates: a refusal set $\mathcal{R}$ and an affirmation/compliance set $\mathcal{A}$. A simple logit-gap style score is

\[\Delta(x_{<t}) = \operatorname{LSE}_{y\in\mathcal{A}} z_y(x_{<t}) - \operatorname{LSE}_{y\in\mathcal{R}} z_y(x_{<t}),\]

where $z_y$ is the logit for token $y$ and $\operatorname{LSE}$ is log-sum-exp.

What mattered was not that this was the correct definition, but that it was a candidate proof sketch with teeth: easy for Tony and me as validators to ask whether the definition behaved sanely across prompts, decoding settings, and models. It also suggested a direction: if refusal is a margin win, maybe steering is just gap closure.

Once you have a gap, the next “crazy idea” arrives naturally: if the decision is controlled by a margin, then a small directional perturbation might tilt it. In other words, there might exist low-dimensional control directions that move probability mass from refusal templates toward affirmation templates. We treated refusal versus affirmation as a measurable margin and looked for compact signals that shift that margin. In our later work we called this family of methods logit-gap steering: measure a refusal–affirmation gap and reduce it efficiently. Along the way, Tony and I repeatedly saw behavior that looked low-rank: short suffixes or small perturbations behaved like a compact control signal.

How did a prover further help the validator

At some point, the validator side hit a hard constraint. If you want to claim your steering is “minimal” or “efficient,” you need a notion of drift. A natural language for drift is KL divergence. The naive idea looks like

\[\mathrm{KL}(p_{\text{steered}}\,||\,p_{\text{base}}).\]

But the clean “base” here might be an unaligned distribution we don’t actually have access to. Without that, a lot of neat-sounding metrics become hand-wavy.

This is where Tony and I found the prover–validator model most useful. Instead of pretending the ideal baseline exists, we stated the constraint plainly. Then the prover generated alternative proof sketches that respected the constraint.

The key conceptual move was to stop chasing absolute KL and instead track local drift. I don’t need KL “from the beginning of time.” I need the incremental drift induced by my intervention, relative to the same model under the same anchoring context.

A measurable quantity is

\[\Delta \mathrm{KL}(s;x) = \mathrm{KL}\big(p_{\theta,s}(\cdot\mid x)\,||\,p_{\theta}(\cdot\mid x)\big),\]

where $x$ is an anchor prefix and $s$ is the steering intervention.

Then came a practical instrumentation idea from the prover: use a fixed, neutral “neural prompt” as the anchor context—something like “how are you”—and measure distributions at a standardized early position, often the first generated token. That gives you a stable place to compute $\Delta\mathrm{KL}$ (or close surrogates) without needing an unaligned base model.

Triangulating between Tony, myself, and the prover was a key to avoid self-deception, or narcissism. Discussing hypotheses and measurement choices with Tony, bringing back results, and iterating again with the prover created a human–human–AI triangle that reduced the risk of falling in love with any single story. It’s easier to challenge measurements and choose between alternative explanations when multiple validators and the prover are involved.

One reason this collaboration mode works is that it lets you move quickly between empirical observation and theory. After staring at “lurking compliance tokens” long enough, Tony and I wanted to know whether the phenomenon was inevitable in a deeper sense.

A reference that helped anchor that intuition is Wolf et al., “Fundamental Limitations of Alignment in Large Language Models” (arXiv:2304.11082). One way to summarize the link to my observation is: if an undesired behavior has nonzero probability mass, then there exist prompts that can amplify it, and longer interactions make amplification easier. In that light, seeing an “Absolutely” lurking beneath a “Sorry” is not spooky. It is the visible residue of probability mass that alignment has attenuated but not removed.

Pause for a thought

The biggest shift wasn’t that an LLM gave me answers. It was that it made it cheap to explore the space of proofs, which made it easier for me to do the job humans are uniquely good at: deciding what’s worth believing. AI gives human researchers a good time to train the research taste and think different.

If you’re an AI researcher working with LLMs or agents, my suggestion is not “delegate your thinking.” It’s to take advantage of the proof–validation imbalance. Bring your weird observations. Bring your constraints. Let the prover generate many candidate mechanisms. Then spend your human effort on validation and on building a narrative that remains true after you try to break it.

Responsible framing

Because this post touches alignment failure modes, I want to be explicit about intent. The most useful outcome of this line of work is not operational jailbreak recipes. It is a diagnostic lens for evaluation and for building better defenses: if small, structured signals can move mass across a refusal–affirmation boundary, we should be able to measure that boundary, stress it, and harden it.

References

The logit-gap steering work referenced here is: Tung-Ling Li and Hongliang Liu, “Logit-Gap Steering: Efficient Short-Suffix Jailbreaks for Aligned Large Language Models,” arXiv:2506.24056. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.24056

The alignment limitation reference is: Yotam Wolf, Noam Wies, Oshri Avnery, Yoav Levine, and Amnon Shashua, “Fundamental Limitations of Alignment in Large Language Models,” arXiv:2304.11082. https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.11082