嗯,用户让我用中文总结一篇文章,控制在100字以内,而且不需要用“文章内容总结”之类的开头。好的,我先看看这篇文章讲的是什么。 文章主要讨论了Azure的Private Endpoint架构中存在一个漏洞,可能导致资源被拒绝服务攻击(DoS)。这个问题可能由内部人员误操作、第三方供应商部署不当或恶意攻击者故意设置引起。研究发现超过5%的Azure存储账户配置容易受到这种攻击的影响。 接下来,文章提到了受影响的服务包括Key Vault、CosmosDB、Azure Container Registry、Function Apps和OpenAI账户。攻击可能导致这些服务无法访问,进而影响依赖它们的应用程序。 微软提供了一些缓解措施,比如启用回退到互联网的选项,但这些措施并不完美。文章还建议进行环境扫描以识别易受攻击的资源,并推荐了一些工具和方法。 最后,Palo Alto Networks提供了相关的安全产品和服务来帮助客户应对这些威胁。 好的,现在我需要把这些信息浓缩到100字以内。重点包括:Azure Private Endpoint漏洞导致DoS风险,三种情况(内部、第三方、恶意),影响的服务类型,微软的缓解措施以及建议的扫描方法。 总结的时候要简洁明了,直接描述内容即可。 </think> 文章揭示了Azure Private Endpoint架构中的潜在漏洞,可能导致资源暴露于拒绝服务(DoS)攻击。该问题可能由内部误操作、第三方部署或恶意攻击引发。研究发现超5%的Azure存储账户易受此风险影响,并涉及Key Vault、CosmosDB等服务。微软提供部分缓解方案如启用互联网回退,并建议通过扫描和配置优化来降低风险。 2026-1-20 17:23:33 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

Executive Summary

We discovered an aspect of Azure’s Private Endpoint architecture that could expose Azure resources to denial of service (DoS) attacks. In this article, we explore how both intentional and inadvertent acts could result in limited access to Azure resources through the Azure Private Link mechanism. We uncovered this issue while investigating irregular behavior in Azure test environments.

The risk is present in three scenarios:

- Accidental - internal: A network administrator deploys Private Endpoints to improve network security within an Azure environment.

- Accidental - vendor: A third-party vendor deploys Private Endpoints as part of its solution, for example to enable resource scanning by a security product.

- Malicious - attacker: A threat actor who gained access to an Azure environment intentionally deploys Private Endpoints as part of a DoS attack.

Our research indicates that over 5% of Azure storage accounts currently operate with configurations that are subject to this DoS issue. In most environments, at least one resource in each of the following services is susceptible:

- Key Vault

- CosmosDB

- Azure Container Registry (ACR)

- Function Apps

- OpenAI accounts

This issue has the potential to affect organizations in multiple ways. For example, denying service to storage accounts could cause Azure Functions within FunctionApps and subsequent updates to these apps to fail. In another scenario, the risk could lead to DoS to Key Vaults, resulting in a ripple effect on processes that depend on secrets within the vault.

Microsoft provides fallback to internet advice that partially addresses this and other known issues associated with Private Endpoints.

We discuss these issues, provide potential solutions and suggest ways that defenders can scan environments for resources that are susceptible to DoS attacks.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed in this article through the following products:

Unit 42 Cloud Security Assessment is a strategic evaluation service that reviews your organization's cloud infrastructure to identify misconfigurations and security gaps, enabling teams to strengthen their posture against cloud-based threats.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Containers, cloud |

Azure Private Link Key Components, Concepts and Flows

As part of Azure’s networking offering, Microsoft created Azure Private Link. This mechanism offers a private, secure way to connect to supported Azure resources and Azure-hosted custom services using Azure’s backbone network.

Definitions

To understand the solution and the secure connection process of resources using it, let’s first define the key components and concepts.

- Service: Destination to which a connection is made

- Private Link: Azure implementation that allows and handles the connections

- Private Endpoint: A network interface within a customer’s virtual network that allows connectivity to the service

- Private DNS zone: The default Domain Name System (DNS) service that is used with Private Endpoints

- Virtual network link: The link created by default between a Private DNS zone and a virtual network

- DNS A record: A DNS record that maps a domain or hostname to an IP address

- Network ACL: Network access control lists (ACLs) define rules that allow or restrict traffic to a service, separate from the Private Link solution

Azure resources expose public endpoints by default. These endpoints resolve through standard DNS infrastructure — either public Azure DNS, or customer-managed DNS resolvers. When a client queries a service name such as mystorageaccount.blob.core.windows[.]net, the DNS resolver returns a public IP address owned by Microsoft. The IP address allows connectivity over the public internet or Azure service endpoints, depending on the network access controls that are applied.

When Azure Private Link is introduced, DNS resolution behavior changes. A Private DNS zone — for example, privatelink.blob.core.windows[.]net — can be linked to one or more virtual networks. If a virtual network has a link to a Private DNS zone for a given service type, Azure’s DNS resolution logic prioritizes that zone when resolving matching service names. If a matching record exists, the name resolves to the private IP address of the Private Endpoint, instead of the public endpoint.

Organizations commonly deploy one of the following architectures:

- Public-only architecture: Resources are accessed using their public endpoints and standard DNS resolution. Network ACLs, firewalls or service endpoints restrict access.

- Private-only architecture: All access to the resource occurs through Private Endpoints. Public network access is disabled, and DNS resolution is fully controlled through Private DNS zones.

- Hybrid architecture (public and private): Some virtual networks or workloads access the resource through Private Endpoints, while others continue using the public endpoint. This model is frequently used during migrations, phased rollouts, third-party integrations, or shared service environments.

We use the example of storage accounts to demonstrate how Private Endpoints are used in Azure networking. However, the same concepts apply to any Private Link-supported service. By default, when a network administrator or a user with appropriate Azure Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) permissions creates a Private Endpoint linked to a resource, a Private DNS zone is created with a virtual network link to the same virtual network as the Private Endpoint.

The DNS zone’s name has a predetermined structure that is based on the Private Endpoint’s destination service (e.g., privatelink.blob.core.windows[.]net for blob storage). Additionally, an A record is created in the DNS zone, linking the name of the destination resource and the IP address of the Private Endpoint.

There are two ways to connect between a virtual machine VM and a storage account with a Network ACL:

- Without a Private Endpoint (using public or service endpoints)

- With a Private Endpoint

Connection Flows

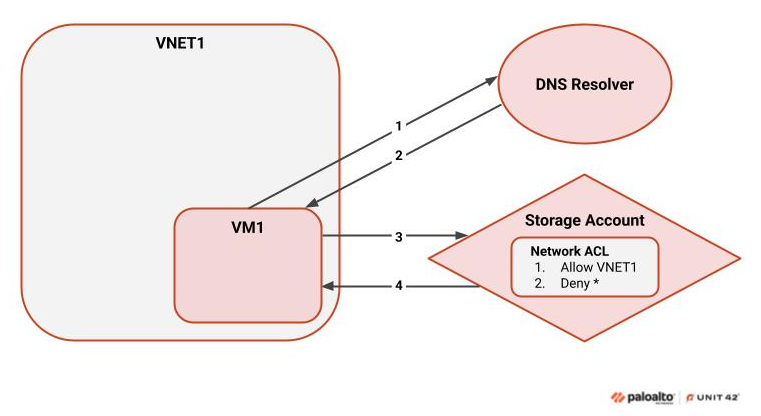

Figure 1 shows how a connection is made to a resource that does not use the Private Link solution.

The flow in this case is as follows:

- When trying to access the storage account, the VM attempts to resolve the account’s name to an IP address. This usually occurs through an external DNS resolver, and the traffic traverses the public internet.

- If the resolver has a record for the storage account, it returns the corresponding IP address.

- Once the address is obtained, the VM tries to connect to the storage account.

- The storage account then evaluates the virtual machine’s IP address against its Network ACL. If the connection is allowed, the storage account responds with the requested information.

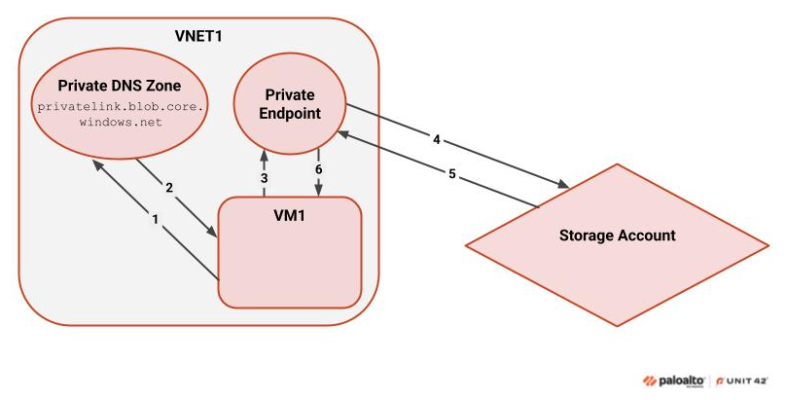

Figure 2 shows how the same connection is made when a Private Endpoint is used.

- Initially, the VM attempts to resolve the account’s name to an IP address. If a virtual network link exists in the virtual network (VNET) to a Private DNS zone that points to a Private Link service, Azure’s Private Link mechanism forces resolution using the Private DNS zone. This occurs when the connection is to a Private Link service of the same type (e.g., blob storage).

- When the DNS resolver identifies a matching A record, it provides the VM with the corresponding IP address.

- The VM then connects to the IP address, which belongs to the Private Endpoint.

- The Private Endpoint acts as a network interface for the storage account, evaluating the traffic and then forwarding it to the storage account.

- The storage account evaluates the request and supplies a response through the Private Link solution.

- The response is presented to the VM, which essentially accesses the storage account using Azure’s backbone network.

Potential Private Link DNS Dangers

As outlined above, interactions with a Private Link service from a virtual network configured with a Private DNS zone for that service type are forced to resolve through the Private DNS zone.

Consider an environment where VM1 in VNET1 successfully accesses a storage account using its public endpoint. DNS resolution occurs through the default public DNS infrastructure, and access is permitted by the storage account’s Network ACLs. At this stage, the workload is operating normally.

Later, a Private Endpoint is created for the storage account in VNET2 — either intentionally, accidentally, or by a third-party deployment. As part of this process, a Private DNS zone for blob storage (privatelink.blob.core.windows[.]net) is linked to VNET1 or shared across virtual networks.

Once this DNS zone is linked, Azure’s DNS resolution logic forces all blob storage name resolution in VNET1 through the Private DNS zone. However, because no “A” record exists in the zone for the storage account within the context of VNET1, DNS resolution fails. VM1 can no longer resolve the storage account hostname and is unable to connect — even though the public endpoint remains accessible and unchanged.

This configuration change effectively creates a denial-of-service condition for workloads in VNET1 that previously functioned correctly. The outage is triggered solely by a DNS resolution side effect introduced by the Private Link configuration, without any change to the target resource itself.

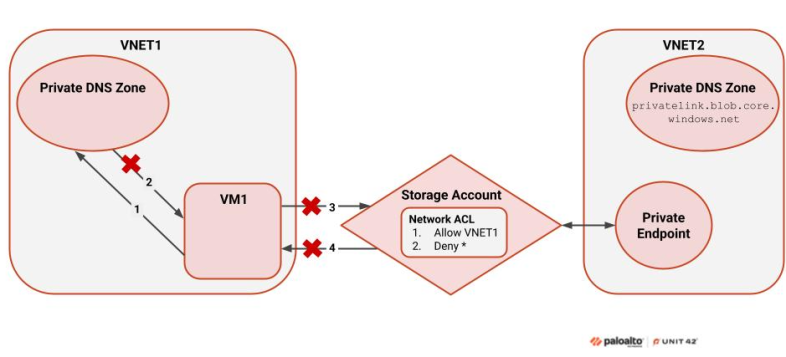

Figure 3 demonstrates this example.

The figure above shows that VM1 attempts to connect to the storage account. This storage account has a Private Endpoint in VNET2 and does not have a Private Endpoint in VNET1. Hypothetically, VM1 could try to connect using the storage account’s public endpoint. This would work if the VM’s virtual network did not have a Private DNS zone resolving to the same resource type. In this case, however, the Private DNS zone and the service are Private Link registered, so Private Link forces resolution through the Private DNS zone.

The process shown in Figure 3 occurs as follows:

- Private Link recognizes the blob storage Private DNS zone in VNET1 and identifies that the storage account is Private Link registered. Private Link forces DNS resolution through the Private DNS zone.

- The configuration in Figure 3 shows that no record was created for the storage account in the Private DNS zone linked to VNET1. As such, the virtual machine cannot resolve the service.

- Due to the DNS resolution issue in step 2, the subsequent steps – in which VM1 sends a request to the storage account and receives a response from it – do not occur.

This scenario causes a partial denial of service: any resource in VNET1 that tries to access the storage account will not be able to.

This risk can also be present when using local DNS resolvers, depending on the configurations and the records added. Additionally, although our example relates specifically to blob storage, any service that supports Azure Private Link is potentially at risk.

Mitigations and Recommendations

Azure Private Link was originally intended as a binary solution, to be either fully enabled, or disabled. When the service is implemented as intended, users can only access resources that use Private Link through those resources' Private Endpoints. This approach eliminates the need to use a combination of private, public and service endpoints. However, as over 5% of Azure storage accounts are configured in a way that is subject to this issue, we recognize the need to provide solutions that address the risks introduced by these implementations.

Mitigations

Microsoft acknowledges that the binary nature of the solution is a known issue and mentions it in their documentation. Microsoft also provides a partial solution: enabling a fallback to internet option when creating a virtual network link. Using this fallback solution, when the DNS Resolver cannot find a record that matches the requested service, it falls back to the public internet. While this solution solves the issue, it does not necessarily match the main concept of Azure Private Link, which is to traverse Azure’s backbone network rather than the public internet.

A second, partial solution is to manually add a record for the affected resource in the necessary Private DNS zone. This option is less appropriate for large production environments, as it creates additional operational overhead.

Although neither fallback nor manually adding a record is a definitive solution, combining the above approaches with comprehensive discovery will help with mapping, finding and remediating affected configurations.

Comprehensive Discovery and Scanning

There are two ways to scan and identify resources that are potentially at risk:

- Scanning for resources with each service individually

- Using Azure Resource Graph Explorer

The second scanning method is more efficient and can easily be modified to match most resource types. We created a graph query that retrieves a list of all the virtual networks in the environment that are linked to a blob storage Private DNS zone (privatelink.blob.core.windows[.]net). These virtual networks are forced to resolve blob storage resources through their Private Endpoints when communicating with Private Link registered resources.

resources | where type == "microsoft.network/privatednszones/virtualnetworklinks" | extend zone = tostring(split(id, "/virtualNetworkLinks")[0]), vnetId = tostring(properties.virtualNetwork.id) | join kind=inner ( resources | where type == "microsoft.network/privatednszones" | where name == "privatelink.blob.core.windows.net" | project zoneId = id ) on $left.zone == $right.zoneId | project vnetId |

In addition, it is important to identify which virtual networks interact with blob storage resources that do not have Private Endpoint connections. We created the following query for this purpose. This query retrieves storage accounts that allow access to their public endpoint and do not have a Private Endpoint connection.

Resources | where type == "microsoft.storage/storageaccounts" | extend publicNetworkAccess = properties.publicNetworkAccess | extend defaultAction = properties.networkAcls.defaultAction | extend vnetRules = properties.networkAcls.virtualNetworkRules | extend ipRules = properties.networkAcls.ipRules | extend privateEndpoints = properties.privateEndpointConnections | where publicNetworkAccess == "Enabled" | where defaultAction == "Deny" | where (isnull(privateEndpoints) or array_length(privateEndpoints) == 0) | extend allowedVnets = iif(isnull(vnetRules), 0, array_length(vnetRules)) | extend allowedIps = iif(isnull(ipRules), 0, array_length(ipRules)) | where allowedVnets > 0 or allowedIps > 0 | project id, name, vnetRules, ipRules |

This query identifies allowed virtual networks and also retrieves resources that allow specific IP addresses. This is useful when there is limited visibility into the DNS configurations for virtual networks, making it difficult to determine whether or not the configurations are affected.

Defenders should be aware that even resources that do not have Network ACLs could still be at risk. However, there is no way to use the configurations to determine which virtual networks, if any, attempt to communicate with such resources. To address this risk, use network logs to identify connections made from Azure network ranges to susceptible resources.

Defenders can change and match the resource and the Private DNS zone details in the above Resources query to detect Private Link-supported resources that are at risk.

Conclusion

Fully understanding the limitations of Azure Private Link is vital to securing networks that rely on it. With certain configurations of components and architecture, the binary nature of Azure Private Link can lead to connectivity loss and in some cases, could enable DoS attacks.

Two of the possible solutions to secure Private Endpoints against this risk include:

- Enabling fallback to public DNS resolution

- Manually adding DNS records for affected resources

Defenders can increase the effectiveness of these solutions by querying resources, conducting comprehensive network scanning to identify resources at risk, and implementing the necessary protections.

Palo Alto Networks Protection and Mitigation

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed in this article through the following products:

- Cortex Cloud customers are better protected from the misuse of the Azure Private Endpoints discussed within this article through the proper placement of Cortex Cloud XDR endpoint agent and serverless agents within a cloud environment. Cortex Cloud is designed to protect a cloud’s posture and runtime operations against these types of threats. It helps detect and prevent the malicious operations or configuration alterations or exploitation discussed within this article.

Unit 42 Cloud Security Assessment is a strategic evaluation service that reviews your organization's cloud infrastructure to identify misconfigurations and security gaps, enabling teams to strengthen their posture against cloud-based threats.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America: Toll Free: +1 (866) 486-4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- UK: +44.20.3743.3660

- Europe and Middle East: +31.20.299.3130

- Asia: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

- Australia: +61.2.4062.7950

- India: 000 800 050 45107

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Additional Resources

- Azure Private Endpoint private DNS zone values – Microsoft documentation

- Azure Private Link availability – Microsoft documentation

- Azure Resource Graph Explorer – Microsoft documentation

- Storage access constraints for clients in virtual networks with private endpoints – Microsoft documentation

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh