文章探讨了渗透测试中常被忽视的访问控制不足、IDOR(不安全直接对象引用)和业务逻辑缺陷等漏洞,强调通过理解应用流程和权限,并创建“滥用案例场景”来识别这些漏洞。通过真实案例展示了IDOR的发现过程,并提供了修复建议。 2025-12-18 09:1:30 Author: blog.nviso.eu(查看原文) 阅读量:9 收藏

Introduction

In many penetration testing assessments, it is common to encounter applications that support multiple user roles, such as admin, normal user, approver, and others.

Consequently, testers are often provided with accounts and credentials for various roles during a grey-box assessment.

During a penetration test, the focus is often on identifying technical vulnerabilities such as Cross-Site Scripting, SQL Injections, and other issues by adhering to testing methodologies or security standards like the OWASP ASVS [1]. However, vulnerabilities such as Broken Access Control, IDORs (Insecure Direct Object Reference), and Business Logic Flaws tend to be overlooked due to their complexity, which requires manual effort and a thorough understanding of the application’s purpose and design.

This article aims to enhance your understanding and testing of these overlooked vulnerabilities. We will define these vulnerabilities and provide insights into distinguishing and assessing them more effectively.

Furthermore, the article will explore the significance and methodology of “Abuse Case Scenarios”, a strategic approach used to identify and validate vulnerabilities through scenarios that are custom-made and specific to each application.

A real-world example related to an IDOR flaw will be presented to demonstrate the effectiveness of this methodology, along with practical approaches and tips.

Finally, we will highlight recommendations and remediation strategies for these vulnerabilities, offering guidance on strengthening the security posture of applications.

Identifying an Application’s Flow and Purpose

Prior to defining and testing Abuse Case Scenarios, the first and most important step is to get a good idea of the purpose of the application. This could contain the following actions:

- Identifying the different user roles within the application

In an application that manages employee leave requests, an employee should be able to submit leave requests. Additionally, appropriate roles such as a manager should have the authority to approve these requests.

- Understanding the permissions and access levels assigned to each role

Should an employee be able to approve their own leave? Is there a specific procedure that is taking place?

- Observing the functionalities and data accessible to each role

Should an employee be able to view or modify their own or other users’ leave?

Understanding the Authorization Mechanism in Place

After starting to get a good idea of the users’ roles and the application’s purpose, the next step is to determine how users and their actions are distinguished. Some examples could be:

- Session Cookies

- JWT Tokens

- API Keys

- OAuth Tokens

- CSRF Tokens

- Identifiers

Creating Abuse Cases Scenarios

After establishing a solid understanding of the application’s purpose, flows, and authorization mechanisms, it is the ideal time to begin defining Abuse Case Scenarios.

Abuse Cases are a list of scenarios that outline actions a user or user role should not be able to perform, given their rights within the application.

These scenarios help outline the structure of the application, such as the flow behind the completion of an action, the differences between user roles, and important functionalities that may be uncovered.

The following is a list of vulnerabilities that these scenarios can discover:

- Incorrect user behavior flow implementation

- Lack of server-side controls

- Authorization issues

- IDORs

- Broken Access Control

- Business Logic Flaws

Due to the uniqueness of user roles and other related features of each application, it is important to note that Abuse Cases differ from application to application, as they are closely related to the application’s functionalities and purpose.

Some examples of Abuse Cases Scenarios are the following:

- As an authenticated user, I should not be able to modify another user’s bank account information

- As an authenticated employee, I should not be able to approve a requested leave

- As an authenticated customer, I should not be able to complete a transaction without making a payment

- As an authenticated customer, I should not be able to alter the price of an item during the purchase process

Invalid Abuse Cases

It is worth to note that technical controls are not Abuse Cases. The following are some examples of invalid Abuse Cases:

- As an authenticated user, I should not be able to perform an SSRF attack via the PDF generation feature

- As an authenticated user, I should not be able to perform a stored XSS attack via the comments section

Additionally, each scenario should be specific and tied to a particular action or feature. For instance the following are some poor examples:

- As an authenticated employee, I should not be able to perform an administrative action

- As a authenticated approver, I should not be able to perform any actions that are restricted for my role

Instead, a better way would be to list each administrative or restricted action. Some examples would be:

- As an authenticated employee, I should not be able to delete a user account

- As an authenticated approver, I should not be able to assign the “manager” role to a user

Finalization and Sharing with the Client

At NVISO, our priority is to provide the highest quality of work while staying closely aligned with the client’s needs. Therefore, once a comprehensive list of Abuse Cases covering the most important and critical functionalities of the application has been created and validated, it is essential to share this with the client. This will allow the client to make any modifications, comments, or add new scenarios if needed.

Note: It is possible that some scenarios may have been overlooked. This is common, as certain testing scenarios require a deeper understanding of user roles or specific functionalities that may not have been initially apparent.

During the testing of Abuse Cases, it is an excellent opportunity to identify additional exploitation scenarios. This iterative process allows for a more comprehensive discovery of potential vulnerabilities.

IDOR vs Broken Access Control vs Business Logic Issues

At this phase, we have developed our Abuse Case scenarios and gained a comprehensive understanding of the application’s user roles and permissions. With this foundation established, we are prepared for the testing process. However, before we dive into this, let’s take a moment to review the definition of the different vulnerabilities. As noted in the previous section, Abuse Cases Scenarios uncover several issues including IDORs, Broken Access Control and Business Logic Issues.

However, these terms are often misunderstood, and their differences are not easily distinguished. Thus, this section will outline the differences between each of the above-mentioned vulnerabilities and provide a methodology to distinguish them.

Broken Access Control (BAC) Vulnerabilities

Broken Access Control represent a broad category of vulnerabilities that occur when an application fails to enforce proper restrictions on the actions that authenticated users or user roles can perform [2].

Note that Broken Access Control encompasses various types of access control failures, including both horizontal and vertical privilege escalations.

Broken Access Control Identification Examples

In the scenario of an application that allows employees to request leave, there may be resources or functionalities that should be restricted based on user roles, such as manager, employee, or admin.

The following are some examples that would help identifying issues of this category:

- Understand user roles and permissions: Start by thoroughly understanding the different user roles within the application and the specific permissions assigned to each role.

In the above-mentioned scenario, only managers should have the ability to approve or reject leave requests submitted by employees.

A vertical privilege escalation vulnerability would occur if a regular employee could somehow access the manager’s interface or interact with the endpoint that is used to approve or reject leave requests.

Additionally, each employee should only be able to view or modify their own leave requests. A horizontal privilege escalation vulnerability would occur if an employee could view or edit another employee’s leave request.

Given the above, employees do not have the ability to approve leave requests by security design, since this action is tied to a privileged role such as the manager role. Thus, Broken Access Control arises if, in some way, this action can be exploited and performed, even though it was never intended to be available for that specific user role.

- Identify application functionalities: Create a diagram or list of critical functionalities.

This will also outline which user roles have access to which parts of the application and what actions they can perform.

- Distinguish client-side or server-side controls: Examine the implementation of access control mechanisms in the application.

In some cases, a web application may impose client-side restrictions when performing an action. However, these restrictions can often be easily bypassed using proxy tools such as Burp Suite or Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP). The following scenarios could be taken into account:

- Unrestricted File Downloads: Some applications do not restrict access to uploaded files based on the user’s permissions or role. This could potentially allow users to access this data by simply accessing the correct endpoint.

- Fuzzing Content discovery: Content discovery may enable unauthorized users to access files or directories. For example, a user could uncover administrative interfaces or configuration files by exploring various URLs.

IDOR Vulnerabilities

Unlike typical Broken Access Control issues, where attackers lack the necessary rights to perform actions, IDOR vulnerabilities occur when an application exposes a reference to an internal object, allowing attackers to manipulate identifiers in requests (such as URLs or API calls) to access resources unauthorized. IDOR exploits often arise from attackers having legitimate access to a specific action but leveraging exposed references to perform unauthorized actions on specific data items or entries that they should not have the permissions to [3].

IDOR Identification Examples

The following are some identification examples of an IDOR vulnerability scenario:

- POST Data: Change the object references in POST data. If a form submission includes a hidden field with a user ID, modify the value to another user’s ID.

- API Requests: Alter parameters in API requests to reference different objects. For example, if an API endpoint /api/orders/456 retrieves order details, change 456 to another order ID.

- Parameter Pollution: Test for parameter pollution by adding multiple instances of the same parameter with different values and notice whether the application processes them incorrectly. As an example, a duplicate GET parameter could look as follows:

https://www.nviso.eu/search?profile_id=user1&profile_id=user2In this case, it is worth paying attention to identifiers that could distinguish data or actions. For this purpose, it is important to gain a thorough understanding of the application’s purpose and structure.

Business Logic Vulnerabilities

Compared to IDOR and Broken Access Control vulnerabilities, Business Logic Flaws arise when an application fails to validate actions correctly according to Business Logic Rules [4, 5].

These rules dictate how the application should behave in specific scenarios and respond to certain actions. By manipulating the Business Logic, attackers can bypass intended workflows or create outcomes that disrupt the application’s intended functionality. Such failures can lead to scenarios where attackers exploit weaknesses in the application’s logic to perform actions not intended by the designers.

Business Logic issues Identification Examples

In the scenario of an application that allows employees to request leave, each employee has a designated leave balance for the year. A Business Logic Flaw in this system could occur if there is a way for an employee to alter their leave balance.

For example, the request flow could be designed in a way, such that the amount of remaining days is only updated once a requested leave has been approved. It could be possible for an employee with 5 days of leave remaining to request multiple blocks of 5 days simultaneously and after approval of them end up with a negative amount of remaining days.

Additionally, here are some examples of Business Logic Issues in different scenarios:

- Using an invalid or already used voucher for a product

- Receiving a product before the transaction is verified

- Exploiting race conditions to purchase multiple products for the price of one

Nevertheless, the following approach would be beneficial during this test:

- Submit invalid data to see if the application properly validates it

- Perform actions out of order to notice whether the application properly handles the workflow

- Analyze server responses by observing how the server behaves when performing specific actions, and document any returned errors or status codes.

The examples above illustrate that Business Logic Flaws are challenging to identify because each application and its functionalities are unique.

Therefore, to thoroughly identify Business Logic Flaws, it is crucial to understand the key business processes and workflows within the application, considering both technical and business perspectives.

IDOR Real-World Example

The previous sections have outlined the differences between these vulnerabilities. This section will provide a real-world example that highlights the importance of creating Abuse Case Scenarios and its effectiveness in revealing and distinguishing IDOR from Broken Access Control issues.

In this example, we encountered a web application that provides two user roles:

- Normal user

- Manager user

Also, there are two teams. The users and managers involved in this example are:

- Luis (normal user, team A)

- Max (normal user, team B)

- Alexandros (manager of Luis, team A)

- Theodoros (manager of Max, team B)

Normal users are able to submit requests, such as leave requests, which need to be validated by their responsible manager. Only the responsible manager should validate the request of the users belonging to the same group.

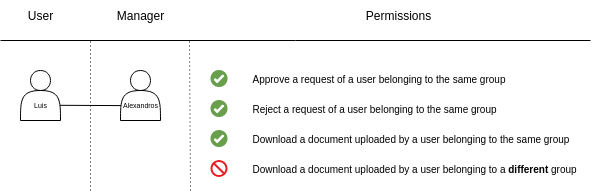

With that being said, the following diagram visualizes the permissions available for the manager user role.

Figure 1: Available permissions for the manager user role

As highlighted, the manager user role should not have the ability to retrieve documents uploaded by users belonging to different groups.

One of the Abuse Cases created to identify whether proper access controls had been implemented by the application was as follows:

- As a manager, I should not be able to download file attachments uploaded by users belonging to another group

In the following example, the normal user named “Luis” has uploaded a file attachment to a request they created. Below, the manager named “Alexandros” reviews the requests created by users belonging to team A. Note that a request containing a file attachment has been created by “Luis”.

Figure 2: Available attachments in the management portal for the manager user “Alexandros”. Luis has uploaded an attachment

The following request/response pair shows the manager “Alexandros” downloading the attachment uploaded by Luis. Note that the GET request contains a parameter named “id”, which consists of a UUIDv4, as seen below:

GET /app/getdocument.axd?id=0203CFD3-223A-4E4E-BCF2-1080E72DF039 HTTP/2

Host: <SNIP>

Cookie: <SNIP>

<SNIP>

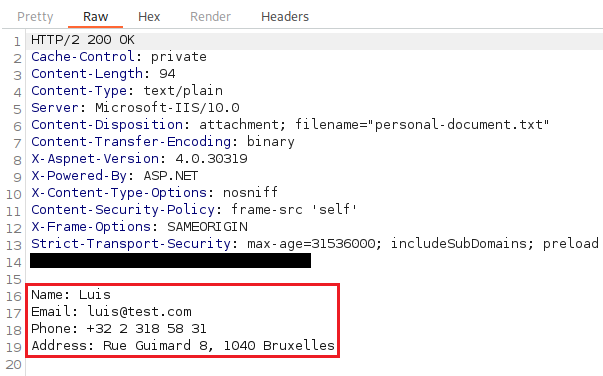

The following screenshot shows the HTTP response of the aforementioned GET request.

Figure 3: HTTP response when the manager user “Alexandros” downloads the attachment uploaded by Luis

So far, this is the intended flow of the web application. However, let’s check whether a manager is able to retrieve files uploaded by users belonging to another group.

Below, the manager named “Theodoros” reviews the requests created by users belonging to team B. Note that a request containing a file attachment has been created by “Max”.

Figure 4: Available attachments in the management portal for the manager user “Theodoros”. Max has uploaded an attachment

Below, the following request/response pair shows the manager “Theodoros” downloading the attachment uploaded by “Luis”.

Figure 5: HTTP response when the manager user “Theodoros” downloads the attachment uploaded by Luis

The last screenshot demonstrates that the application is not correctly implementing access control, as a manager can retrieve files uploaded by users in a group managed by a different manager. This flaw is caused due to the presence of Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR). Specifically, the “id” parameter used in the GET request to retrieve a file can be manipulated by users, allowing them to access files that should not be accessible.

Example conclusion

Abuse Cases are effective in identifying vulnerabilities, such as those resulting from Insecure Direct Object References (IDORs). In this example, an IDOR vulnerability allowed managers to access files from other teams, leading to authorization issues.

It’s important to note that this example highlights an IDOR vulnerability, not a Broken Access Control issue. The manager role inherently has the ability to download attachments uploaded by users within their group. However, the direct reference to the document identifier can be exploited to retrieve documents from users in different groups, leading to an IDOR vulnerability.

As a result, IDOR vulnerabilities arise when an application exposes direct references to internal objects without proper authorization checks, allowing users to manipulate these references and gain unauthorized access.

Recommendations & Remediation Techniques

Recommendations for Broken Access Control

To prevent Broken Access Control vulnerabilities, it is crucial to take the following measures into consideration:

- Access controls should validate access to a resource continuously, with access control based on the authenticated user’s session. It is important to ensure that access is validated server-side for every request, rather than relying solely on client-side checks.

- Implement Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) by clearly defining roles and associated permissions. Ensure that RBAC is enforced consistently across all application layers and endpoints.

- Deny by Default: Follow the principle of least privilege. Users should only be granted the minimum access necessary to perform their tasks.

- Secure coding practices may contribute to avoid exposing internal implementation details.

- Comprehensive Logging and Monitoring: Log access control failures and alert on suspicious access attempts to enable prompt detection and response.

- Regular Access Reviews: Periodically review user roles and their permissions, particularly following major product releases or changes.

Recommendations for IDOR (Insecure Direct Object Reference)

It is important to note that direct object identifiers should never be exposed to users. Instead, an additional layer of abstraction should be implemented, where a relative identifier is mapped to an absolute identifier on the back end [6].

- Indirect References: Avoid exposing database keys or predictable IDs in URLs or request parameters. Use indirect references such as UUIDs or opaque identifiers.

- Ownership Validation: Always verify that the authenticated user has ownership or the necessary permission to access or modify the referenced object.

Recommendations for Business Logic Issues

Since Business Logic Issues require a better understanding of the business requirements and needs, it is crucial to define and document business rules. This involves a clear documentation of Business Logic requirements and expected workflows. These should be well understood by both development and QA teams. The following techniques can also be considered:

- Abuse Case Testing: Develop test cases that specifically target potential abuse scenarios, such as privilege escalation, workflow manipulation, or bypassing process steps.

- Separation of Duties: Where applicable, separate critical functions and require multiple conditions or approvals for sensitive operations.

- Continuous Review: Regularly review and update Business Logic as requirements evolve, and ensure that changes are reflected in both code and documentation.

Observations and Tips

The previous sections have outlined the importance of using Abuse Case scenarios and their effectiveness in revealing vulnerabilities such as IDOR or Business Logic flaws, as highlighted through real-world examples. This section will provide some observations and tips that can be used to strengthen a penetration testing methodology and approach.

Note 1: While testing Abuse Cases Scenarios, improper error handling may occur, providing an opportunity to observe the server’s response. Often, sensitive information or user permissions and roles may be revealed, which could be exploited to expand attack vectors.

In other cases, applications might fully handle errors and refrain from disclosing any information in HTTP responses. However, by analyzing the application’s behavior and examining the HTTP responses, it may be possible to gain a better understanding of the underlying system or framework in use. This could potentially open up additional attack vectors.

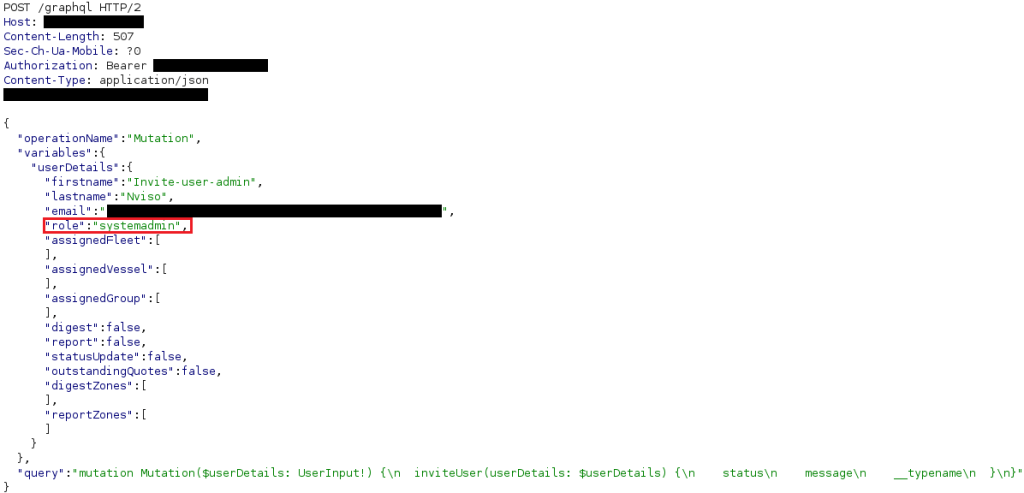

In a real-world scenario, an application included a feature that allowed users to invite others by specifying their email addresses. During this process, the HTTP request contained a parameter used to identify the role of the user for whom the invitation would be created. As illustrated in the screenshot below, the role “systemadmin” was specified in the request.

Figure 6: “systemadmin” user role specified in the HTTP request

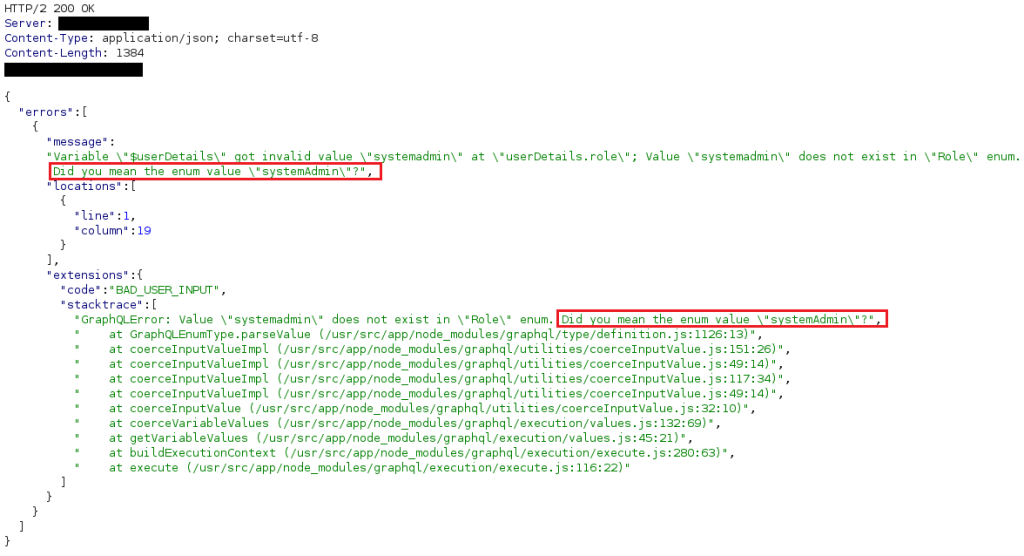

However, during the creation of an invitation, the application discloses information about the existence of specific user roles. In this case, “superAdmin” appears to be the correct role to use.

Figure 7: “systemAdmin” user role revealed in the HTTP response

Although this specific application implemented custom error messages, it was possible to retrieve important information about a user role by examining the HTTP responses. In this case, the issue was not related to improper error handling but to GraphQL suggestions being enabled [7].

Even though the application initially appeared to have no access control issues, the fact that GraphQL suggestions were enabled allowed further enumeration of its behavior, revealing a valid user role named “superAdmin”. This discovery could potentially be leveraged to explore additional attack vectors.

Note 2: Although the defined Abuse Cases Scenarios include scenarios involving authenticated users or roles, it is important to check whether actions can be performed from an unauthenticated perspective, particularly those initiated by users with higher privileges.

Note 3 : Consistently utilize the HTTP response manipulation technique, as it can sometimes be useful for bypassing sequential steps.

Note 4: Automating processes where possible is beneficial for efficiently and accurately testing Abuse Cases Scenarios. The Auth Analyzer [8] extension is a valuable tool for this purpose, offering effective ways to utilize Burp Suite for testing authorization-related scenarios. Further details on this Burp Suite extension can be found in the references section.

References

[1] OWASP Top 10 team. “OWASP Application Security Verification Standard (ASVS)”, https://owasp.org/www-project-application-security-verification-standard/. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[2] OWASP Top 10 team. “A01 Broken Access Control”, https://owasp.org/Top10/A01_2021-Broken_Access_Control/. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[3] OWASP Top 10 team. “Testing for Insecure Direct Object References”, https://owasp.org/www-project-web-security-testing-guide/latest/4-Web_Application_Security_Testing/05-Authorization_Testing/04-Testing_for_Insecure_Direct_Object_References. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[4] OWASP Top 10 team. “Business Logic Vulnerability”, https://owasp.org/www-community/vulnerabilities/Business_logic_vulnerability. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[5] PortSwigger. “Business Logic Vulnerabilities”, https://portswigger.net/web-security/logic-flaws. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[6] OWASP Top 10 team. “Insecure Direct Object Reference Prevention Cheat Sheet”, https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Insecure_Direct_Object_Reference_Prevention_Cheat_Sheet.html. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[7] PortSwigger. “GraphQL suggestions enabled”, https://portswigger.net/kb/issues/00200513_graphql-suggestions-enabled. Accessed 10 December 2025.

[8] PortSwigger. “Auth Analyzer”, https://portswigger.net/bappstore/7db49799266c4f85866f54d9eab82c89. Accessed 10 December 2025.

Alexandros Georgopoulos

Alexandros is a Cybersecurity Consultant and Penetration Tester on NVISO’s Software and Security Assessments team. Holding a Master of Engineering (M.Eng) in Electrical and Computer Engineering from NTUA, Athens, he has a deep passion for cybersecurity and continually strives to enhance his skills and knowledge. His strong time-management, organizational, and communication skills have enabled him to succeed in complex projects.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh