In the lead up to the 2024 US presidential election on Nov. 5, Democratic candidate 2024-11-5 01:0:54 Author: www.bellingcat.com(查看原文) 阅读量:29 收藏

In the lead up to the 2024 US presidential election on Nov. 5, Democratic candidate Kamala Harris’ campaign mentioned the phrase “Donald Trump” more than they did “Kamala Harris” in advertisements that ran on Facebook and Instagram. Meanwhile, ads sponsored by the official campaign for her Republican rival Trump relied heavily on the slogan “Make America Great Again,” popularised during his 2016 presidential campaign, in their messaging on the same platforms.

This guide outlines how we used Meta’s free-to-use Ad Library to extract and analyse data about both candidates’ political ad spending on Facebook and Instagram to get a sense of how they were approaching digital advertising on these platforms.

These methods could also be useful for other elections and political events, as ad spending data from tech platforms can provide researchers and journalists with insights into trends that often align with a campaign’s offline strategies.

The data we extracted from Meta’s Ad Library showing ads run by Trump and Harris’ campaigns on Facebook and Instagram from July 21 – when Harris succeeded incumbent president Joe Biden as the Democratic Party’s nominee – to Oct. 30, 2024 can be found here. The code we used to analyse the data can be found here.

Getting Started With Meta’s Ad Library

The Meta Ad Library is a resource that provides details of ad spending across Meta’s platforms – including Facebook, Instagram, the Meta Audience Network and Messenger – in a specific time period.

Anyone can view and search the Ad Library, but you need to be logged into a Facebook account to download data from it.

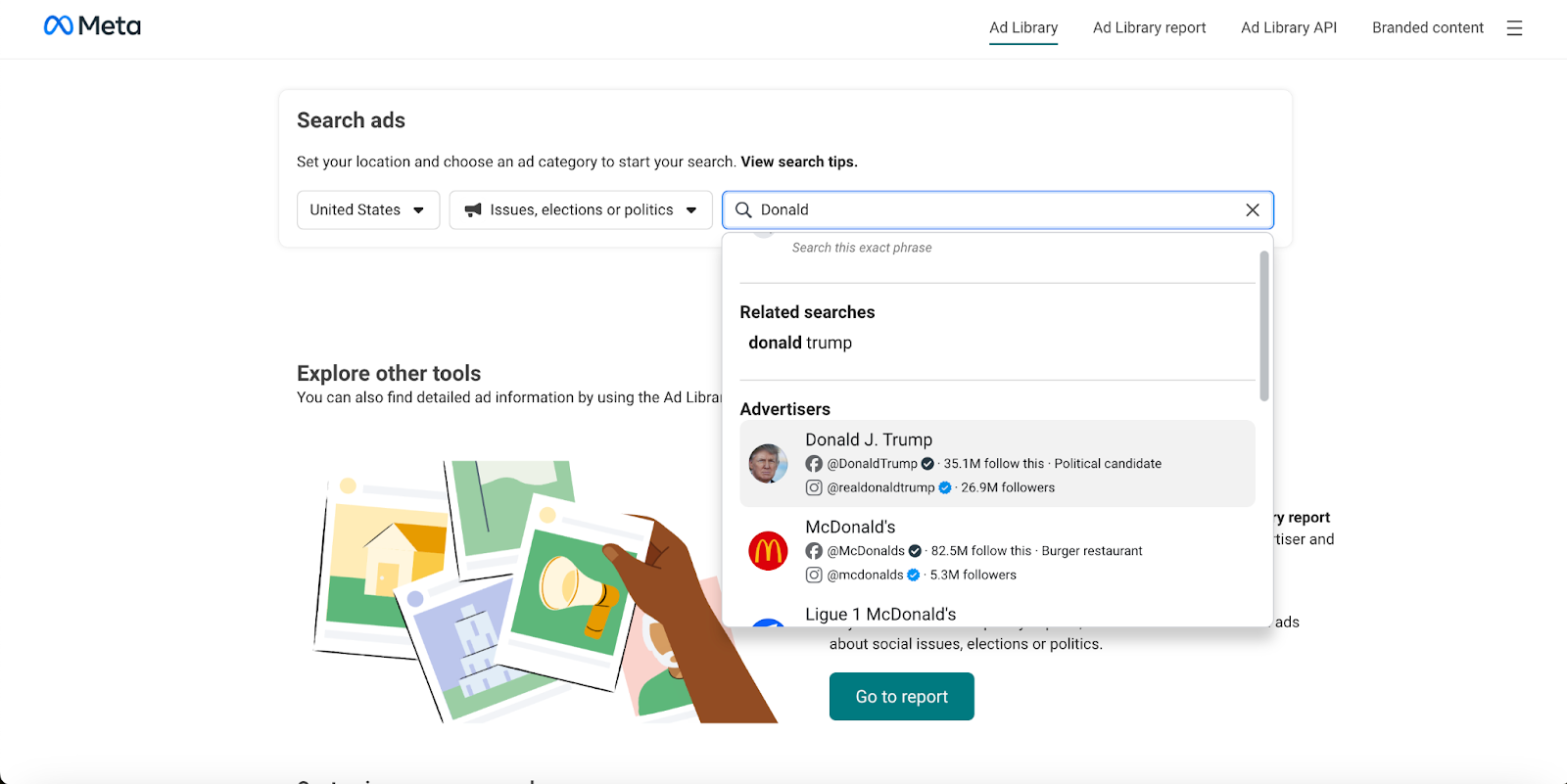

The first step for searching through the Ad Library is to fill in the country targeted, ad category and either keywords that appear in the ad, or the name of the page posting the ad, referred to as “advertisers”.

Note that by default, the results only show ads that people can currently see, or “active ads”. In many cases, you may want to change this to include all ads, including those that ran in the past but are no longer active. You can do this by clicking the “X” on the tab that says “Active status: Active ads”, or click on “Filters” to change the “Active status” to “Active and inactive”.

In the “Filters” view you can also narrow the results by the platform that the ads appear on, the date range that they were shown to audiences and other variables.

For all of the advertisers included in our analysis, we looked at both active and inactive ads with impressions in the US from July 21 to Oct. 30, 2024. We did not filter for language, platform, media type or audience size.

When you have the desired results, you can click on “Export CSV” to download them. However, a limitation of the Meta Ad Library is that each Facebook account can only download three of such files a day.

Expanding the Search

When looking at data for the Democratic and Republican candidates, Harris and Trump’s official accounts were an obvious starting point. However, their campaigns’ spending was not limited to ads running from these accounts. CNN reported last month, for instance, that the Harris campaign had spent US$11 million on an obscure page called “The Daily Scroll”.

Meta policies state that all ads about social issues, elections or politics must be labelled with a disclaimer that reflects the organisation or person paying for the ads.

You can filter the initial results from your search by the names mentioned in these disclaimers (i.e. the ad sponsor). However, if you are looking to find all ads paid for by the same sponsors – which would give a fuller picture of the ads sponsored by each candidate’s campaign across different pages – it becomes more complicated.

In the example above, “Harris For President” – Harris’ official campaign committee – is listed in the disclaimer as the sponsor for an ad posted by Harris’ official account. However, searching for its name as a keyword returns not only ads paid for by the committee, but also those where the phrase “Harris For President” appears in the body of the ad – for instance, a message that says “Vote Kamala Harris for President!” in an ad sponsored by another organisation.

A more reliable way to identify ads sponsored by the candidates’ official sponsors is to go to the “About” section on their official accounts, which provides information about all the sponsors associated with that page, as well as other pages that share those sponsors.

Bellingcat downloaded all ads published by pages that share an ad sponsor with the official pages of Harris and Trump.

We then removed ads with sponsors not listed on the candidates’ pages, to limit the results to those associated with the candidates’ official campaigns.

In total, we found 17 different advertisers with ads sponsored by Harris’ campaign, and six with ads sponsored by Trump’s official campaign.

Making Sense of the Data

The files downloaded from the Meta Ad Library includes details on the ads such as the pages and platforms they appeared on, the dates they were created, which states they targeted, a range for the amount spent and the text and links that appeared with each ad.

They are available in CSV file format, which can be viewed and edited with common spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets. However, we found it more efficient to do further processing of the data with Python, a programming language known for its simplicity.

For instance, the column “delivery_by_region” contains data on where people who saw the ad were located, as a percentage of the total. In the case of the US election data we downloaded, these regions consisted of the 50 US states.

This data would be useful to see where the campaigns might have been targeting their advertisements, but the percentages for each ad appear in a single cell in a spreadsheet, making it hard to compare ad delivery in specific states.

With some Python code, we were able to separate the rows into individual columns by state, which made it easier, for example, to calculate the approximate amount of money each campaign spent on ads shown in each state.

The column with demographic information, showing what percentage of an ad was aimed at a specific gender within different age groups, can be handled in a similar way.

The data from Meta’s Ad Library does not show a specific amount of spending for each ad, but rather gives a range with an “upper limit” and “lower limit” reflecting the maximum and minimum amounts spent on the ad respectively. For the purposes of this analysis, we used the average of these two figures for all of our calculations to give an estimate of the spending by both campaigns.

Total Spending

By summing up the average spending for all ads by each presidential candidate’s campaigns, we found that Harris’ campaign has spent about US$113 million – more than a small country’s GDP – advertising on Facebook and Instagram between July 21 and Oct. 30, while Trump’s campaign spent about US$17 million in total.

Both figures likely represent just the tip of the iceberg for the candidates’ total ad spending across television and digital advertising including on other online platforms such as Google.

Almost all (99.8 percent) of the ads sponsored by Harris’ campaign ran on both Facebook and Instagram, whereas almost 26 percent of those supporting Trump were only shown on Facebook, and 7.5 percent targeted only Instagram.

This is only a fraction of both campaigns’ and their supporters’ spending on ads. An NPR analysis published on November 1, found that over $10 billion has been spent in the 2024 election cycle, beginning January 2023, on races from president, senate to county commissioner. This includes ads on TV, radio, satellite, cable and other digital ads.

Estimating Ad Spend by Region

To estimate how much each campaign spent advertising on Meta’s platforms, we multiplied the average spending for each ad with the the percentage of ad delivery for each region (the data previously extracted from the “delivery_by_region” column), assuming that the amount spent in each region was proportional to where audiences eventually saw the ad.

Based on our calculations, the Harris campaign directed more advertising dollars in swing states with the highest spending in Pennsylvania – reported as the toughest swing state by election strategists – than any other state.

Pennsylvania played a crucial role in the 2020 election with Biden winning by a narrow margin. The state backed Trump in the 2016 election.

The seven swing states – Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – are regarded as holding the key to the White House in the 2024 election. The Trump campaign has also focused on the swing states, but Democrats have outspent Republicans in each of those states.

Calls to Action

Given that these ads were running in the months immediately leading up to the presidential election, there were several clearly identifiable calls to action related to the polls: asking people to vote for the candidate, soliciting donations, fundraising through official merchandise and promoting physical rallies.

We wrote a Python function tagging these calls to action for text-based ads using URLs associated with them – for example, an ad pointing to “vote.donaldjtrump.com” is likely to be meant to encourage people to vote, while “secure.actblue.com” is the Democratic Party’s official fundraising platform, so all ads pointing to that were tagged “donate”. There were similar URLs we identified for official merchandise stores and event websites which were used for rallies.

Additionally, we looked for the keywords “vote” and “donate” in link titles and link descriptions.

This method was able to categorise almost all ads from the data from the Trump campaign’s dataset as “vote”, “donate” or “rally”. Only three ads – all with the same messaging criticising Harris’ position on fracking without an explicit call to action, were unclassified.

The Trump campaign is primarily using these ads to ask people to vote and donate, but about one in five ads we analysed were promoting his rallies.

Harris’ campaign had a less clear focus in their calls to action. Almost half of the ads we analysed could not be easily classified by the categories we defined as many of them promoted news articles covering a wide range of topics. Of those we could label using the method described, most were seeking donations.

The Democrats’ campaign seemed to have much less of an emphasis promoting physical rallies, with ads focusing on this accounting only for 1.5 percent of the total.

Most Frequently Mentioned Word Combinations

To get a rough idea of the key themes in each campaign’s ads on Facebook and Instagram, we used a Python tool that helps break down text into unique word combinations and count them.

We chose to focus on two-word combinations or phrases, which provide more context than individual words but are still relatively easy to analyse. To ensure we only got meaningful phrases, we excluded a known list of common words such as “the” and “a” which appear frequently in any text but do not carry much meaning on their own.

We also removed specific times such as “4:00PM” as they cropped up often in rally promotion ads but did not tell us much about the ad messaging.

Note that there are many possible approaches to processing textual data such as ad copy, and the one we chose may not be the best for all use cases. For instance, it may make more sense to leave in the words we removed if you are looking for word combinations such as “in the news”, where common words such as “in” and “the” play a part in identifying the phrase.

Nonetheless, the approach we chose revealed several interesting trends.

The pair of words that appeared most frequently in the Democratic campaign’s ads was “Donald Trump”, with their own nominee’s name following in second place.

Harris’ campaign also often mentioned Project 2025, a proposal by conservative American think tank Heritage Foundation that aims to “pave the way for an effective conservative administration”. In the run-up to the elections, the Democratic Party has often used this initiative to attack Trump, while the Republican candidate has tried to distance himself from it.

The Harris campaign ads in our dataset that invoked Project 2025 sounded alarms over its alleged consequences on reproductive rights, gun laws, education and taxes, and accused it of giving unchecked power to the president.

Meanwhile, the most common such phrase mentioned by the Republican camp, unsurprisingly, was “President Trump”. Trump’s campaign also often alluded to “MAKE AMERICA” and “AMERICA GREAT”, clearly in the context of “Make America Great Again”, the political slogan popularised by Trump during his successful 2016 campaign.

This analysis also revealed a key difference in the strategies of both campaigns: while none of the Trump team’s top word pairs referred to specific issues or policies – instead including many strong action-based phrases such as “request ballot” and “get tickets” – Harris’ campaign discussed the “middle class” and “reproductive freedom” in many of their ads.

Conclusion

The Meta Ad Library is a good resource to start from for anyone interested in monitoring elections by looking at the ads candidates are posting on Facebook and Instagram.

Our analysis was limited to only ads posted by groups affiliated with Trump and Harris’ official campaigns, but it may also be looking into other ad sponsors supportive of each candidate, such as political action committees (PAC) and groups for both Democrats and Republicans.

The ads on Meta’s platforms present a small window of insight into the massive publicity campaigns for both candidates in the lead up to Election Day on Nov. 5, especially in swing states, where voters have reported being bombarded with robocalls, texts, campaign visits, billboards, flyers and other digital ads. This could be combined with analysis of data from other sources, such as Google’s Ads Transparency Centre, for a fuller picture.

Tristan Lee contributed research to this piece.

Featured image: Reuters/Mike Segar

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh