Executive SummaryIn July 2024, researchers from Palo Alto Networks discovered a su 2024-10-11 05:0:46 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:158 收藏

Executive Summary

In July 2024, researchers from Palo Alto Networks discovered a successor to INC ransomware named Lynx. Since its emergence, the group behind this ransomware has actively targeted organizations in various sectors such as retail, real estate, architecture, and financial and environmental services in the U.S. and UK.

Lynx ransomware shares a significant portion of its source code with INC ransomware. INC ransomware initially surfaced in August 2023 and had variants compatible with both Windows and Linux. While we haven't confirmed any Linux samples yet for Lynx ransomware, we have noted Windows samples. This ransomware operates using a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) model.

This article delves into the timeline of these more recent attacks and the evolving tactics employed by the threat actor behind this ransomware.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from Lynx ransomware through our Network Security solutions and Cortex line of products.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Ransomware, Double Extortion |

Activity Timeline

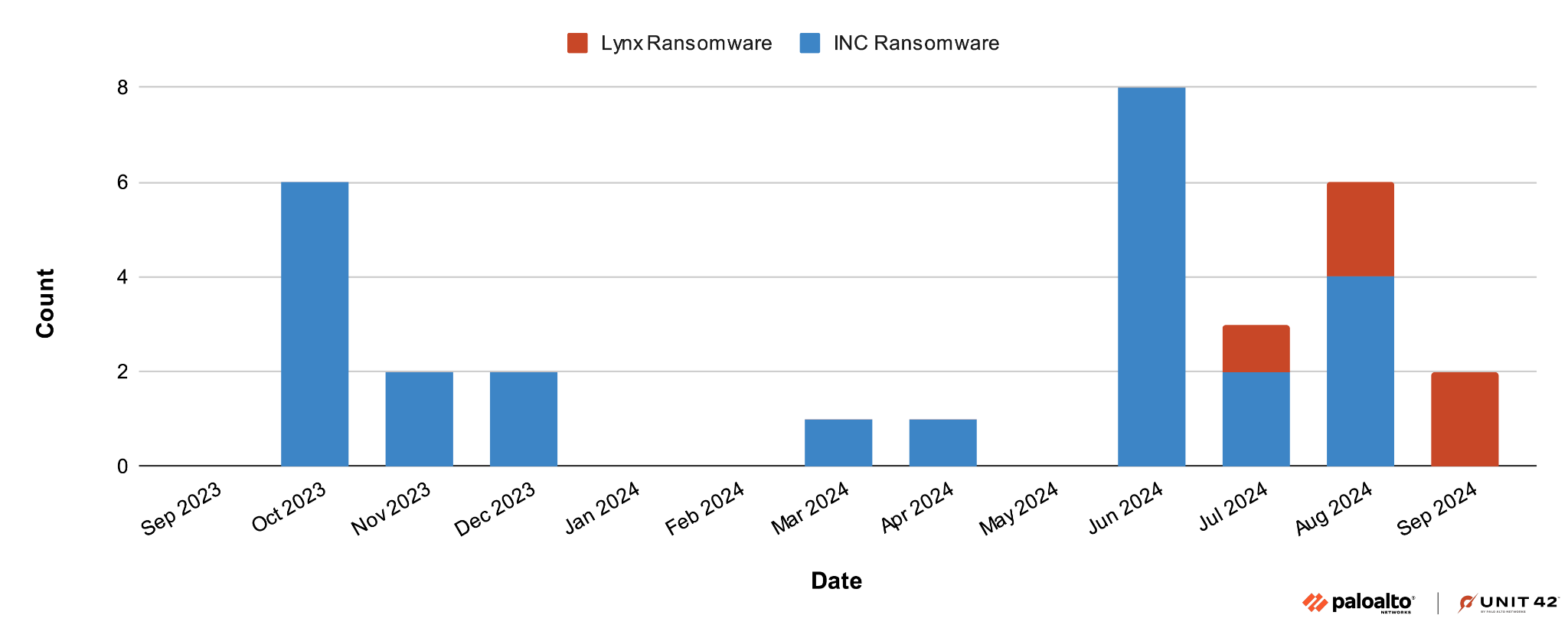

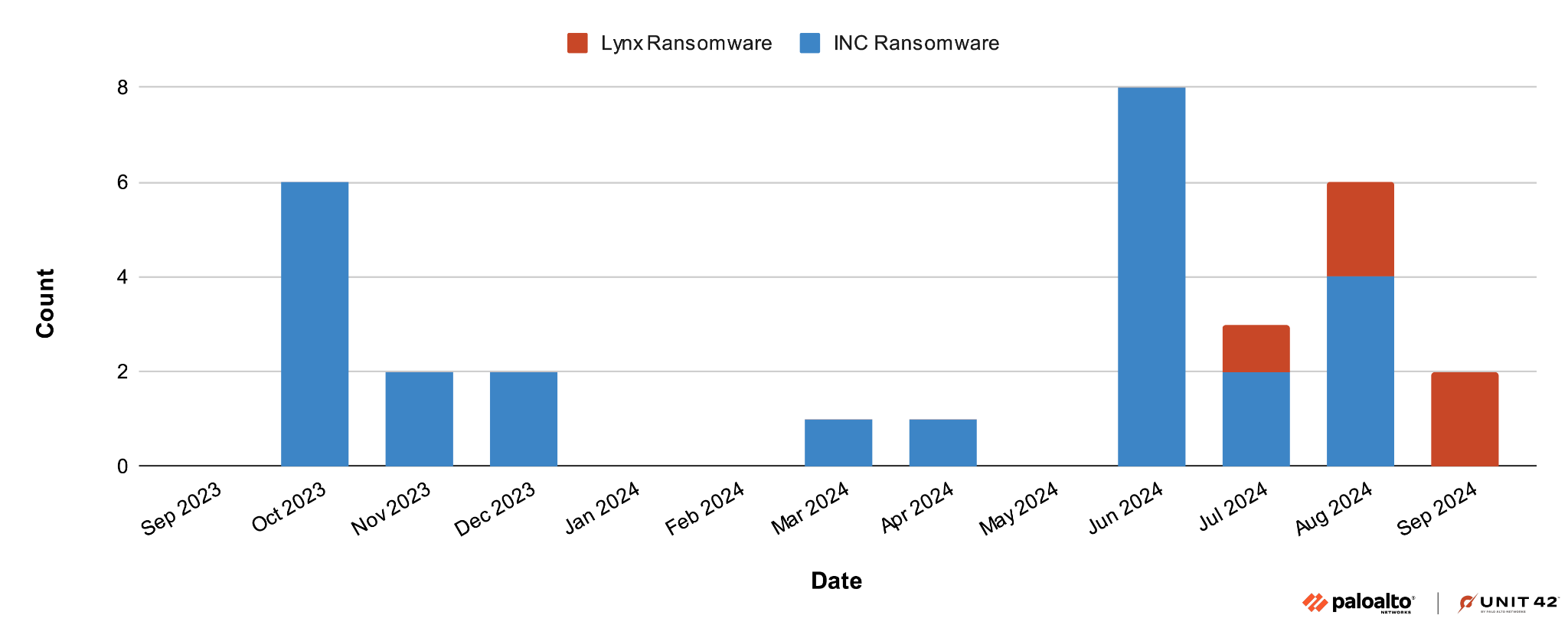

Figure 1 below shows a timeline comparing the number of confirmed samples we have discovered for both INC and Lynx ransomware. This graph presents a comparison of the sample count for both INC and Lynx ransomware on a monthly basis from October 2023 through September 2024.

The source code for INC ransomware was available for sale on the criminal underground market as early as March 2024. Because of this, we expect many malware authors to acquire and repackage this code to develop new ransomware, similar to what the Lynx group did. As a result, we can expect a growing trend in which newer or different ransomware groups reuse this existing code.

Delivery Mechanism

The group behind Lynx ransomware represents an increasingly prevalent and sophisticated double-extortion threat. The threat operators commonly disseminate their ransomware through a variety of cyberattack vectors.

These vectors include:

- Phishing emails that deceive users into revealing sensitive information

- Malicious downloads that surreptitiously install the ransomware onto victims' systems

- Hacking forums where cybercriminals share information and resources

The double extortion aspect of Lynx ransomware means that it exfiltrates a victim's data before encrypting it. This not only encrypts the victim's data, rendering it inaccessible, but also allows the ransomware group to leak or sell this information if the victim does not make a ransom payment.

Like other ransomware groups, this multifaceted approach to cyberextortion has made Lynx ransomware a formidable threat to individuals and organizations alike. This necessitates organizations to develop robust cybersecurity measures to counteract its impact.

Data Leak Site

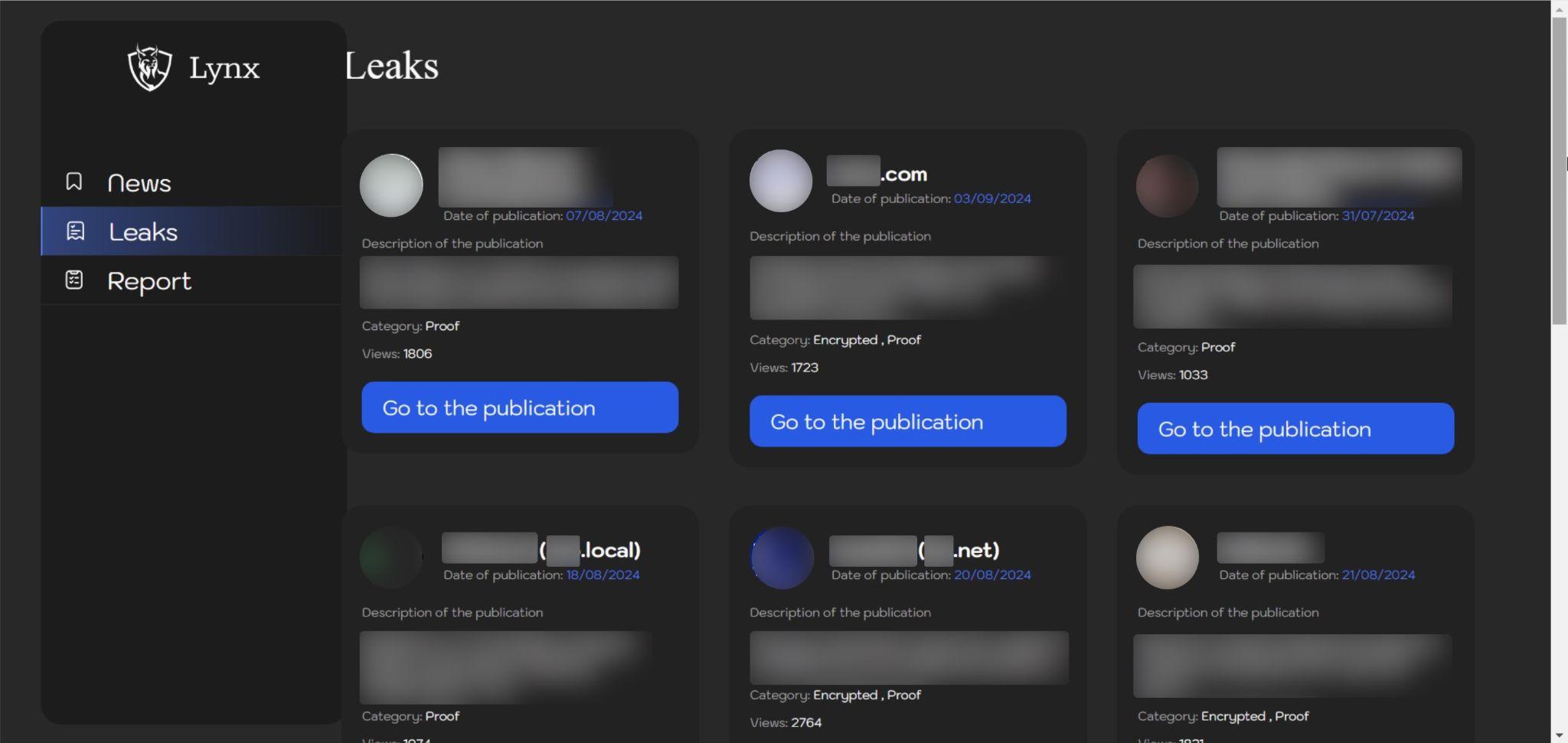

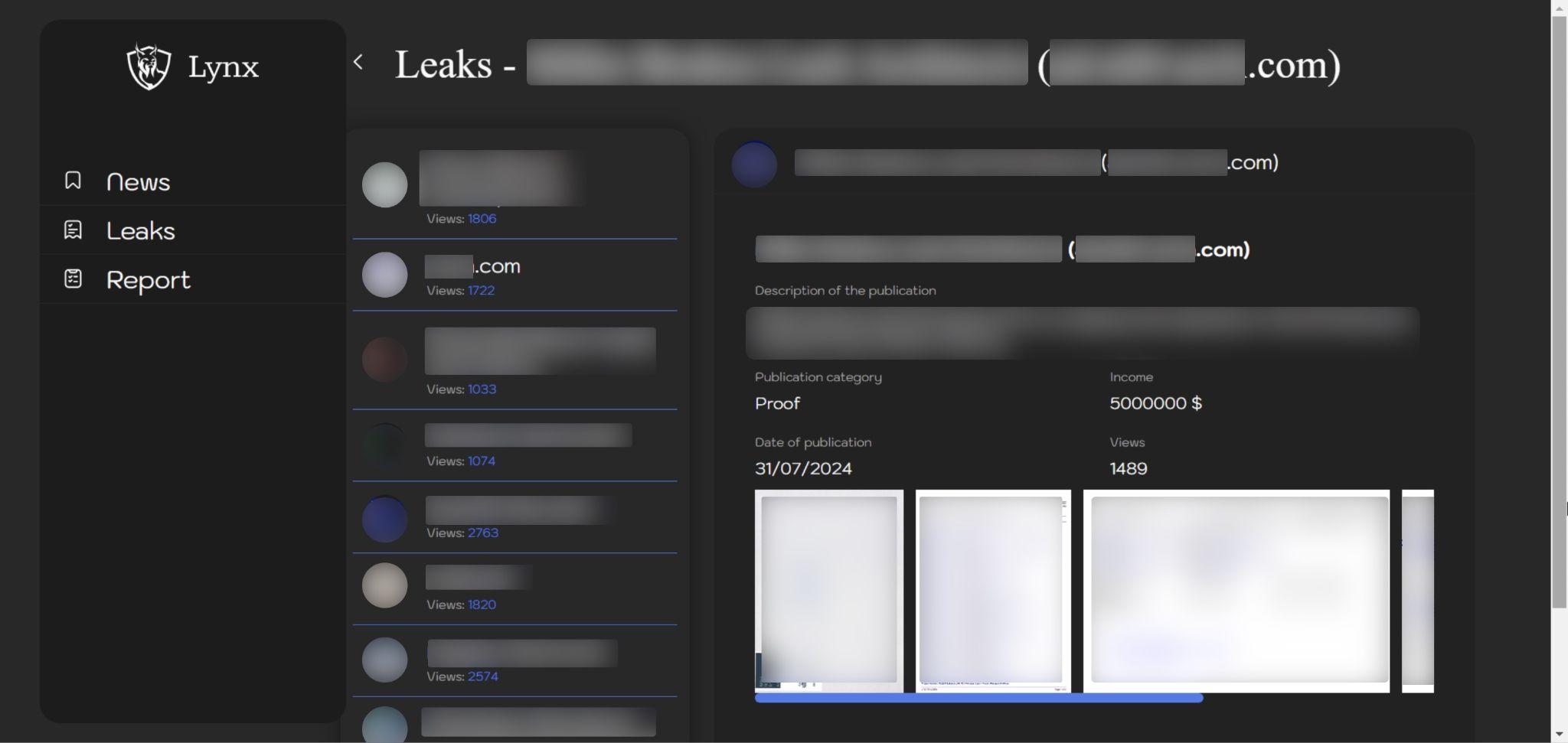

The group asserts that it has breached data from numerous companies and has publicly displayed the pilfered information on its website at http[:]//lynxblog[.]net as demonstrated in Figures 2 and 3.

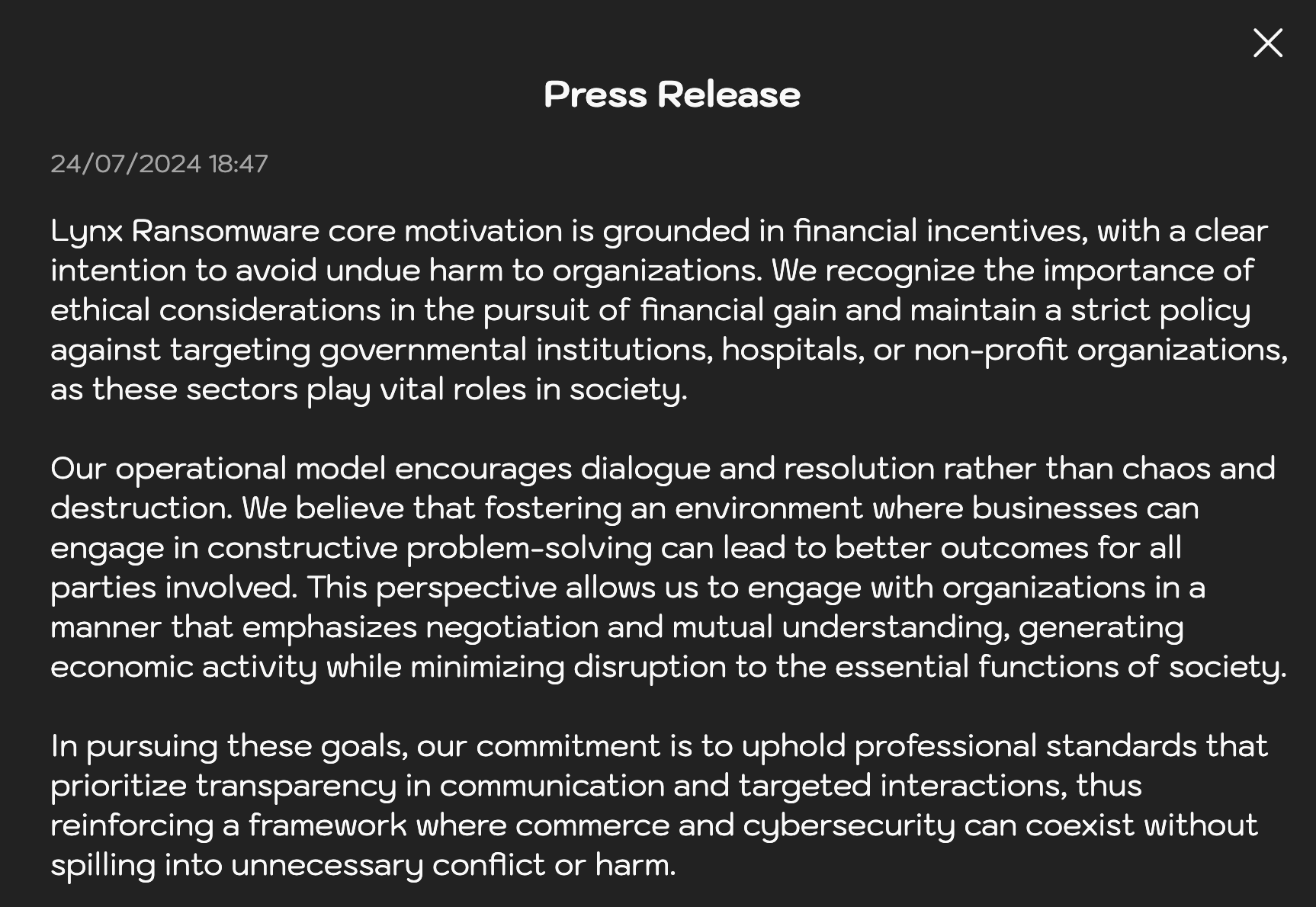

The group has a strict policy and recently released a statement on their activities as shown in Figure 4. This group states it is financially motivated, but it claims it does not target government institutes, hospitals or non-profit organizations.

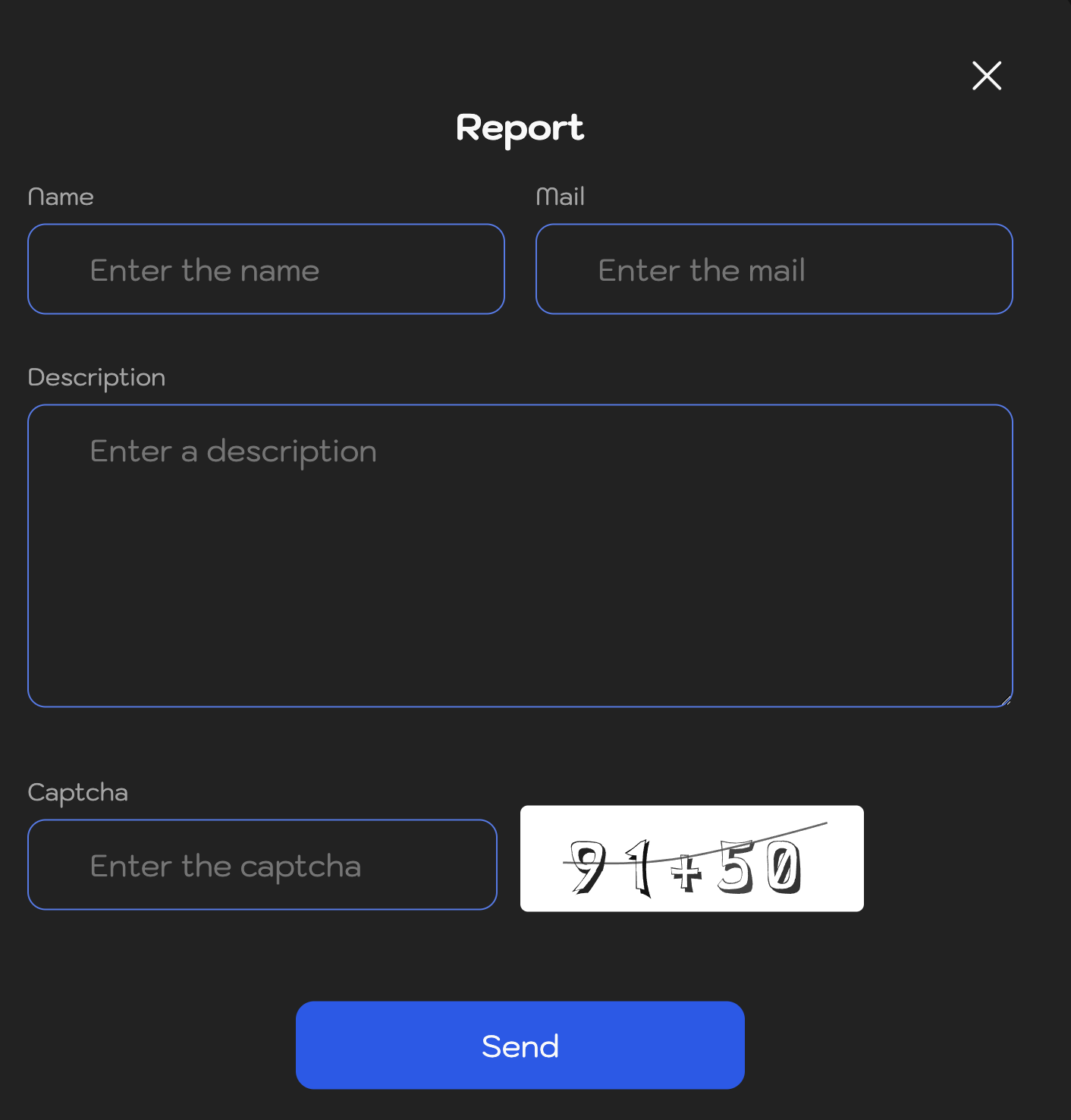

This group has also created a reporting page for its operations as shown in Figure 5.

Below, Figure 6 highlights the logo used for Lynx ransomware as seen on its website.

Technical Analysis of Lynx Ransomware

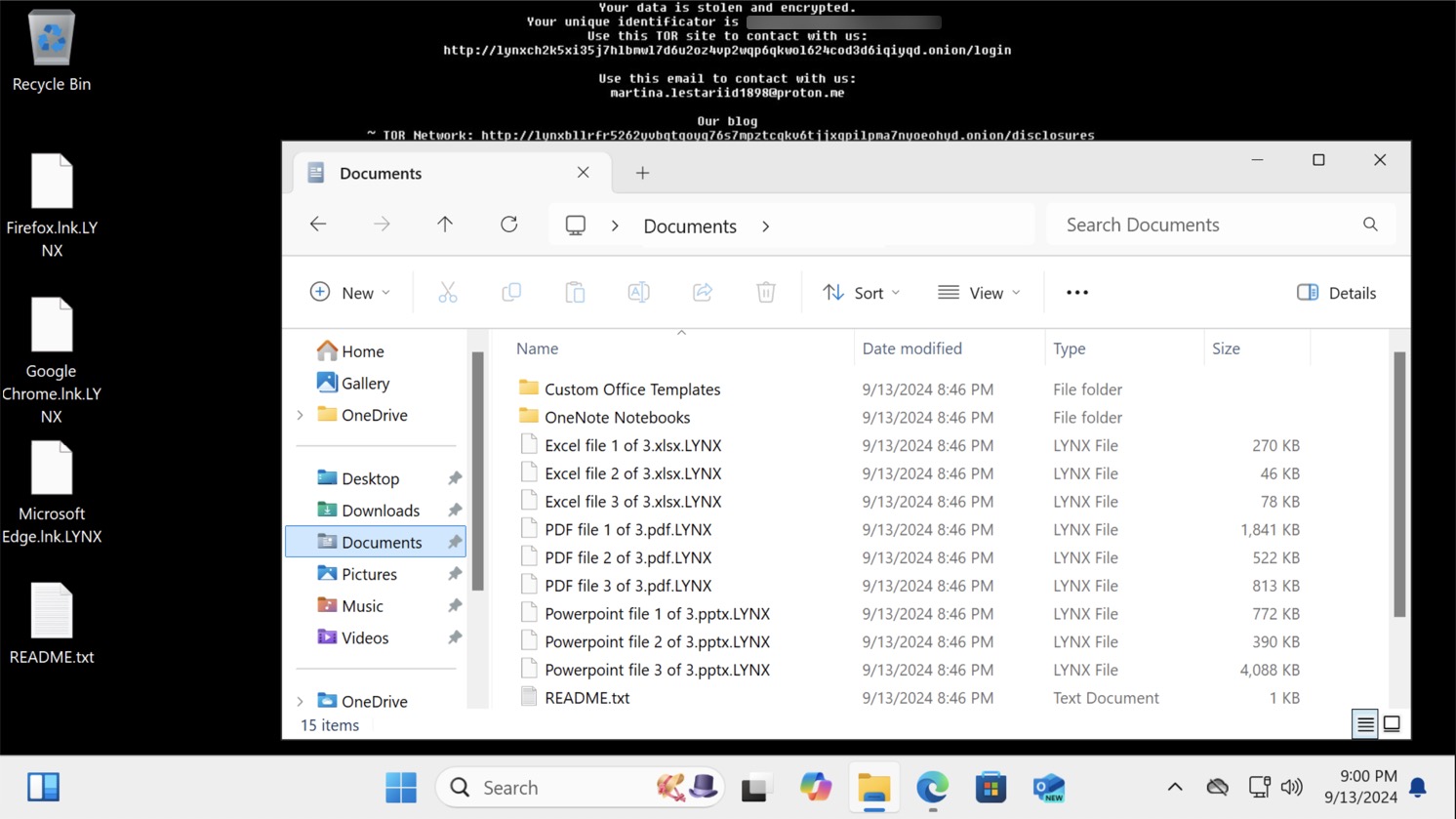

The Lynx ransomware samples we analyzed used AES-128 in CTR mode and Curve25519 Donna encryption algorithms. All files are encrypted and have the .lynx extension appended to them. This malware version is designed for the Windows platform and is written in the C++ programming language.

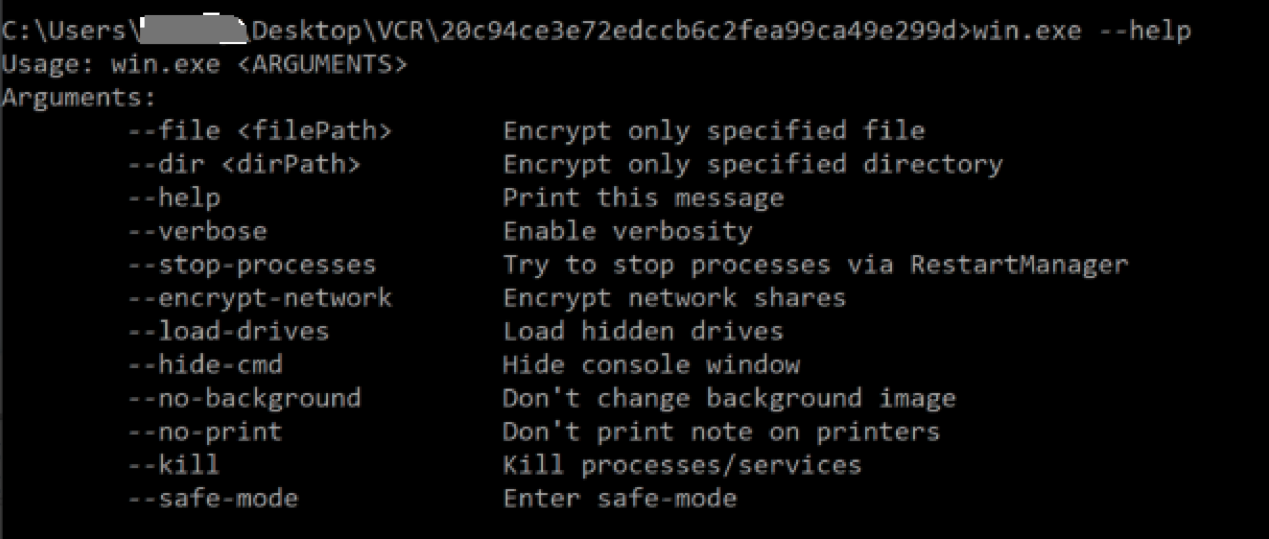

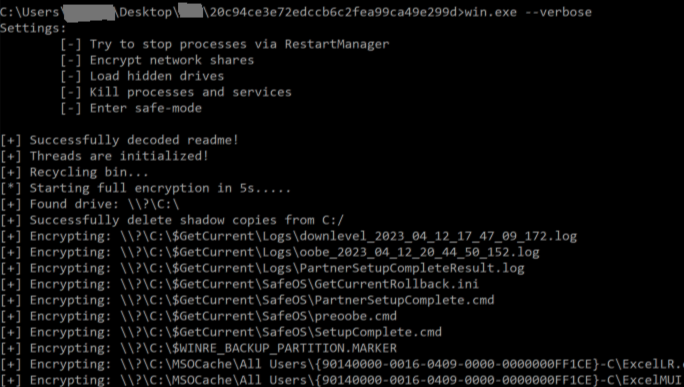

Attackers can tailor their execution of Lynx ransomware by using arguments supplied during runtime as illustrated in Figure 7.

The ransomware’s features include the following:

- Designating specific directories/files for encryption

- Terminating services/processes

- Encrypting network drives

- Mounting concealed disks

- Enabling or disabling background image alterations

- Printing all console logs

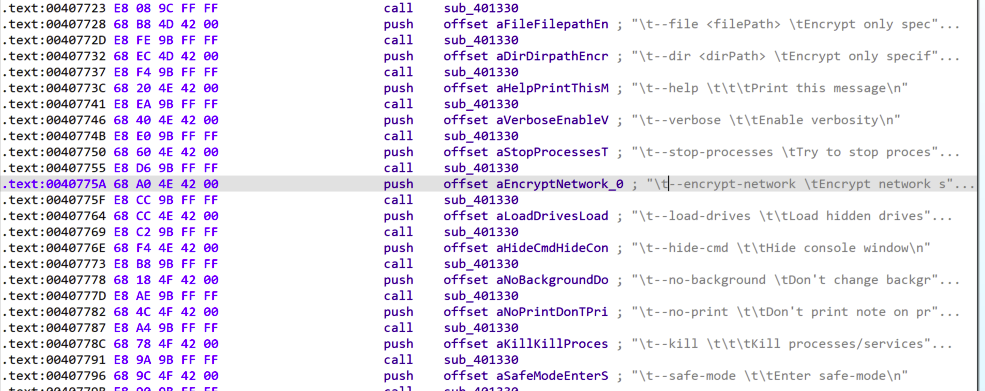

Figure 8 shows code snippets for various arguments available for Lynx ransomware. It can even load hidden drives and encrypt network share drives.

If no arguments are given, the ransomware defaults to encrypting all files and drives on the system. Additionally, it deletes shadow copies and backup partition drives as shown in Figure 9.

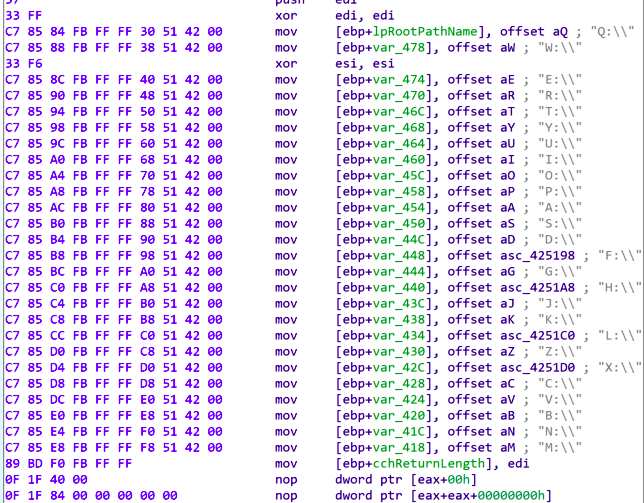

As noted from the debugger results in Figure 10, the ransomware scans all the drives, attempts to mount them, then encrypts the data they contain.

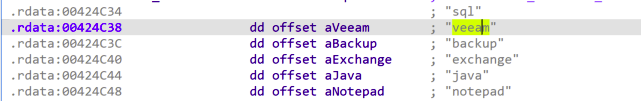

Before starting the encryption process, the sample would kill the processes on the system listed in Figure 11 below.

Figure 12 shows code snippets illustrating this process.

Like many other ransomware strains, Lynx ransomware uses the Restart Manager API RstrtMgr to enhance its encryption capabilities and maximize its impact on the victim's system. By incorporating RstrtMgr into its attack process, Lynx ransomware can target files that are currently in use or locked by other applications.

RstrtMgr helps the ransomware identify which applications are using the desired files. Ransomware such as Conti, Cactus and BiBi Wiper have also been observed employing this technique.

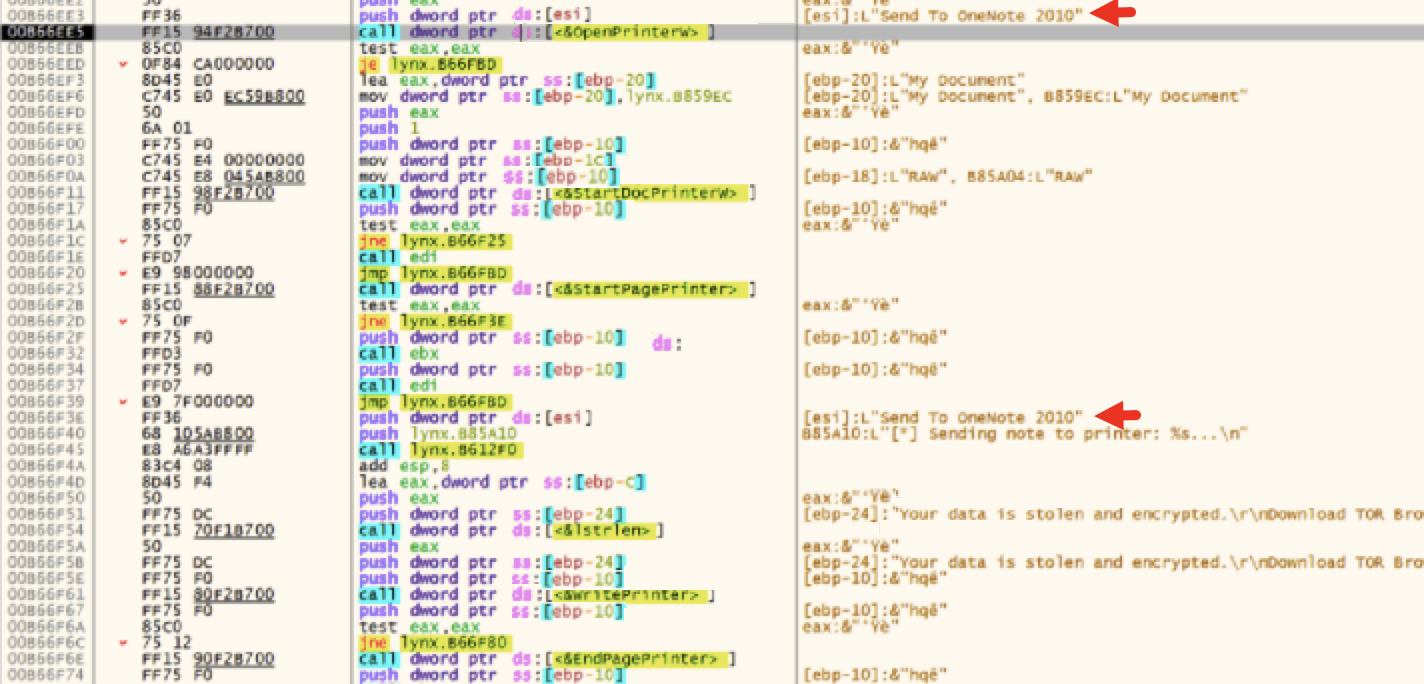

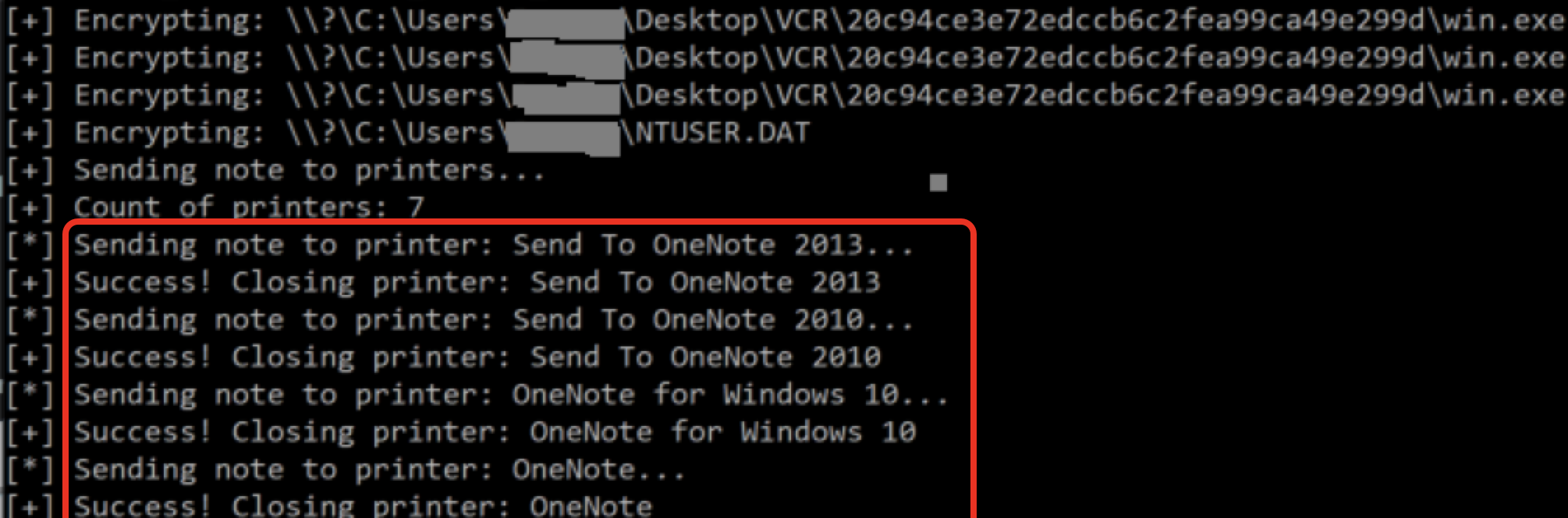

After the ransomware encrypts all files, it attempts to print a report via Microsoft OneNote as shown in the debugger output in Figure 13 and the command-line output in Figure 14.

Figure 15 below shows that the ransomware appends a .lynx extension to all encrypted file names.

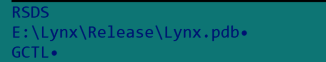

The presence of a program database (PDB) path with Lynx in the name confirms the ransomware as a Lynx variant, as shown in the output of a packed executable (PE) analyzer tool in Figure 16.

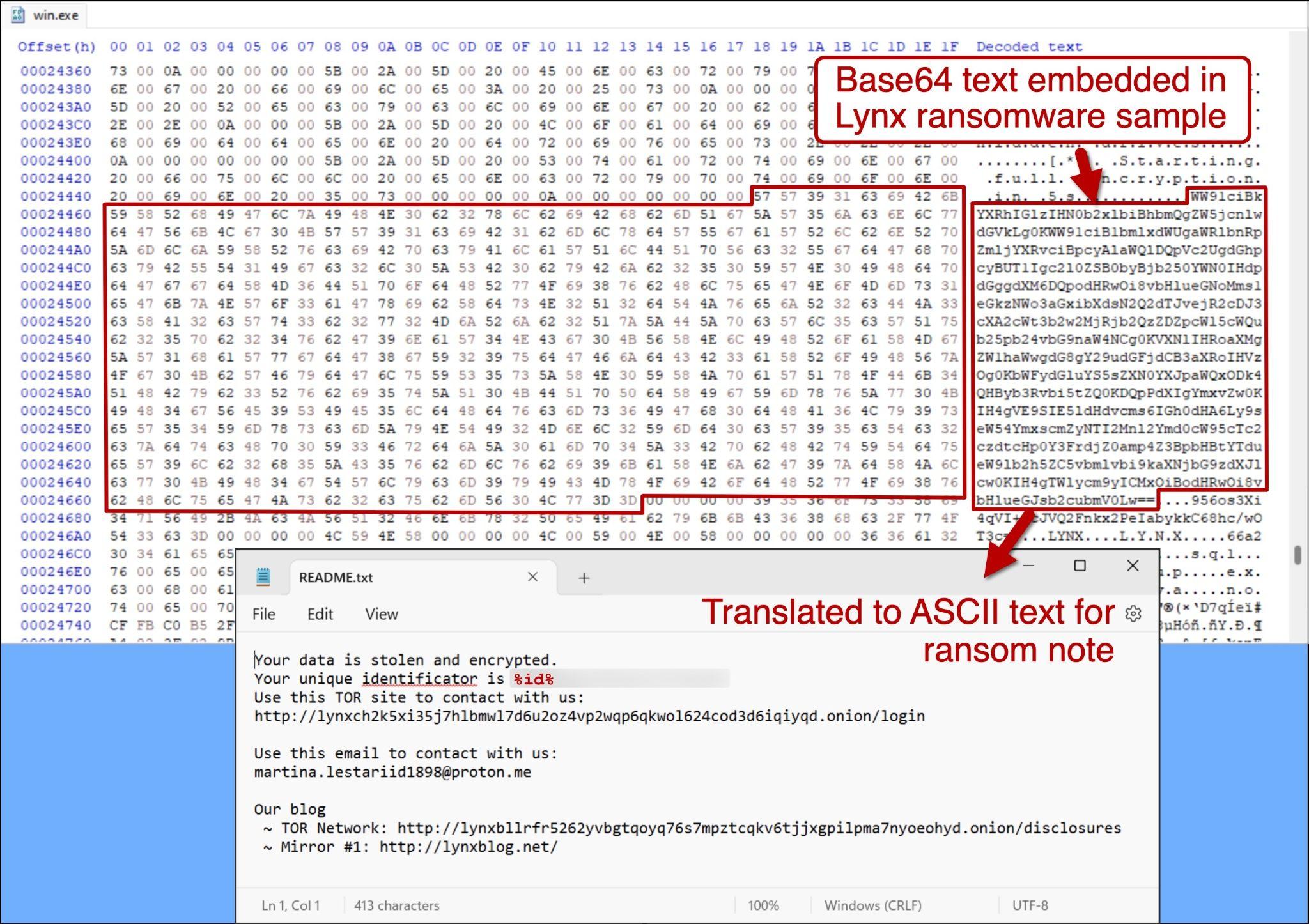

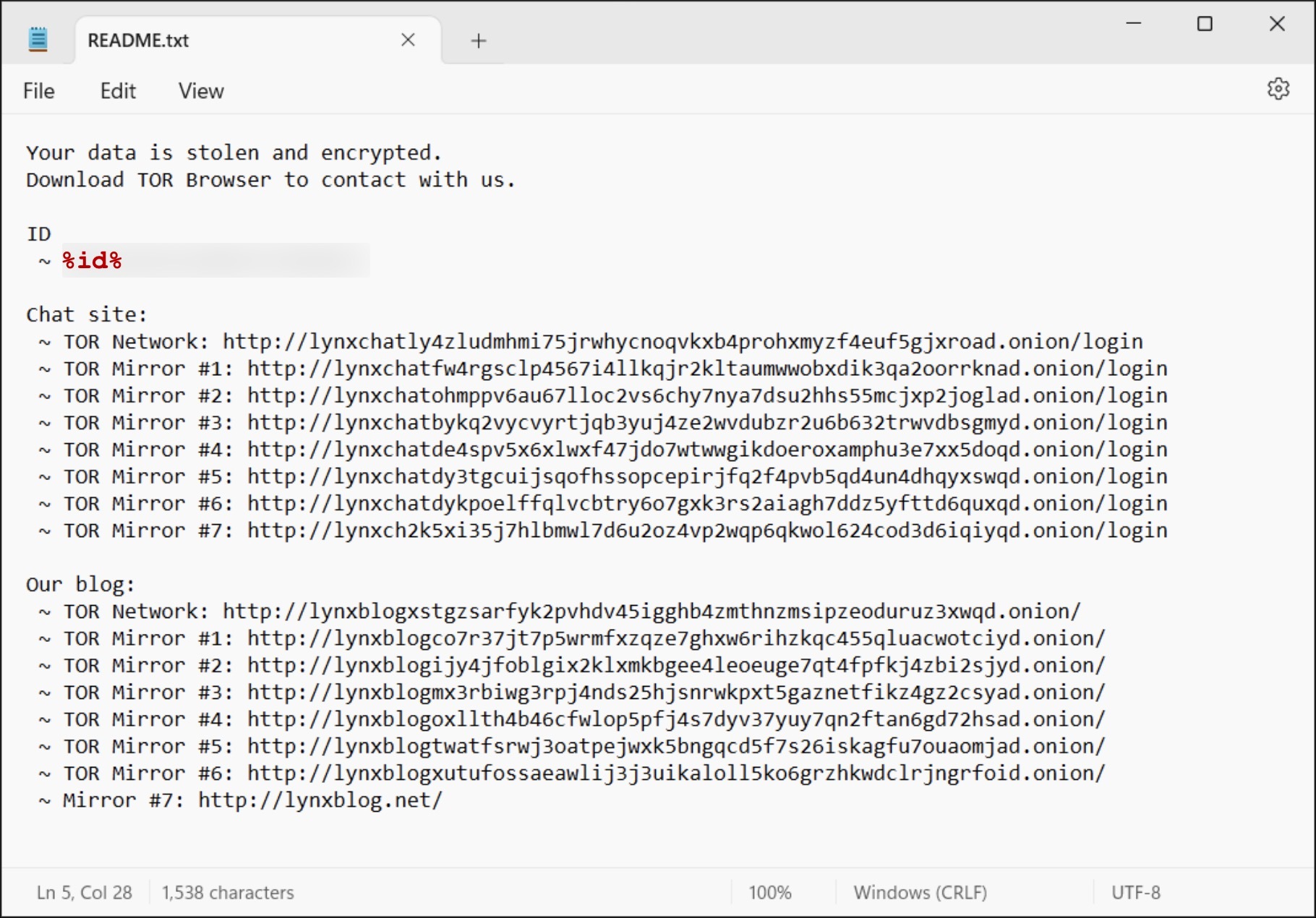

Lynx additionally drops a README.txt file as a ransom note. Figure 17 displays both the Base64-encoded content found in the sample data section of a Lynx ransomware sample and the decoded ransom note.

Figure 18 below shows a different ransom note from another Lynx ransomware sample.

Comparison With INC Ransomware

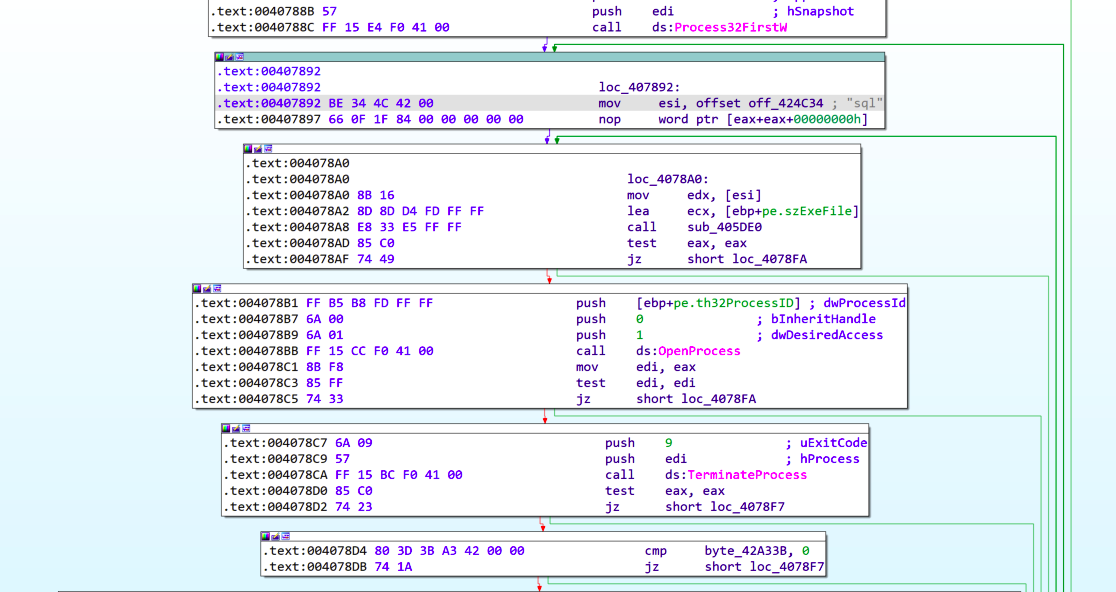

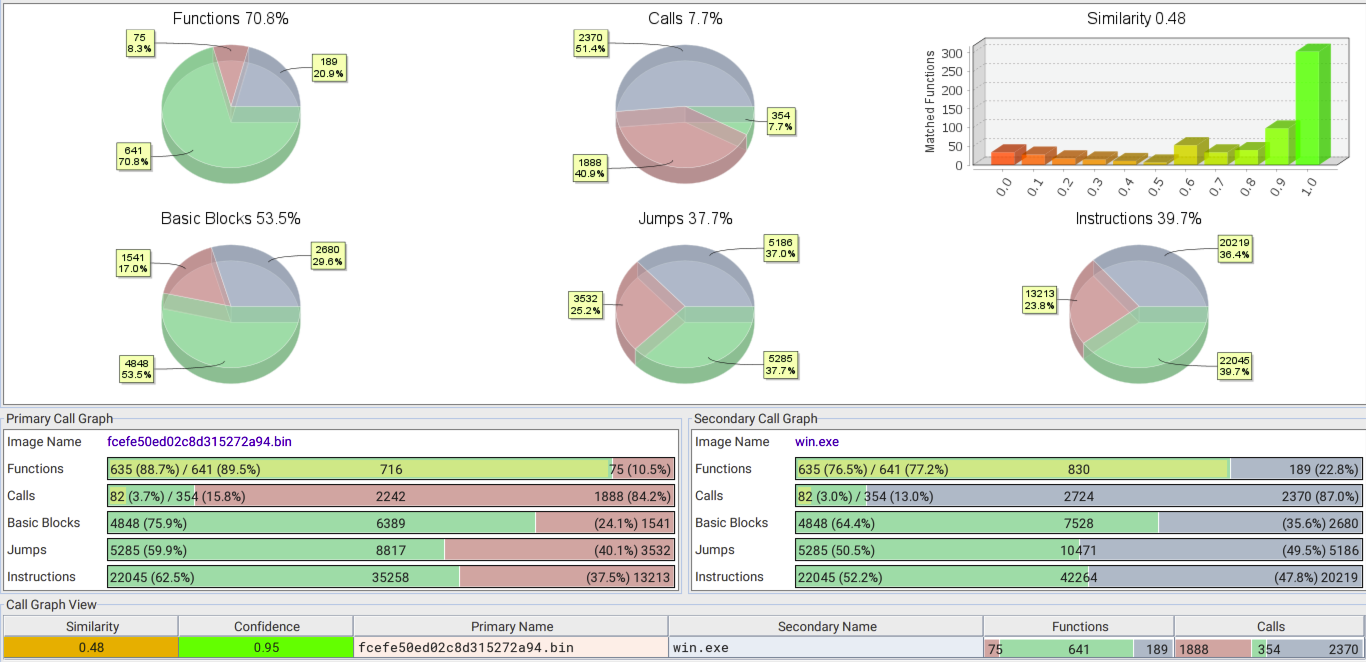

We used the open-source tool BinDiff to compare the code between a sample of Lynx ransomware and a sample of INC ransomware. Figure 19 shows the BinDiff results from the INC sample in the Primary Call Graph (bottom right) and the Lynx sample in the Secondary Call Graph (bottom left). By analyzing and cross-referencing the call graphs of both ransomware samples, we can observe the extent to which their code structures and functionalities overlap and diverge.

Upon close examination, we find that the overall matched functions between both ransomware samples stand at 48%. This indicates that nearly half of the functions present in the INC ransomware sample are also used in the Lynx sample.

The percentage of matched functions rises to an impressive 70.8% when we consider functions that are common to both ransomware families. This significant overlap in shared functions strongly suggests that the developers of Lynx ransomware have borrowed and repurposed a considerable portion of the INC codebase to create their own malicious software.

Reusing code between different ransomware families is common among cybercriminals. By leveraging preexisting code and building upon the foundations laid by other successful ransomware, threat actors can save time and resources in the development of their own attacks. This can ultimately lead to more successful and widespread campaigns.

Conclusion

Lynx ransomware use is active and evolving, yet attackers often employ similar code patterns in newer versions. Palo Alto Networks monitors such campaigns and uses various static and dynamic methods for detecting and blocking them.

Ransomware is a familiar presence in the threat landscape, and there are numerous approaches to protecting customers from these evolving attacks. These methods include dynamic and behavioral detections, as well as more reactive signature or pattern-based solutions.

Palo Alto Networks Protection and Mitigation

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from Lynx ransomware through the following products:

- The Cortex XDR Anti-Ransomware module protects against the threats described in both versions of the malware: Windows and Linux.

- Advanced WildFire: The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of the IoCs shared in this research.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

SHA256 hashes of Windows EXE samples for Lynx ransomware:

- 571f5de9dd0d509ed7e5242b9b7473c2b2cbb36ba64d38b32122a0a337d6cf8b

- 82eb1910488657c78bef6879908526a2a2c6c31ab2f0517fcc5f3f6aa588b513

- eaa0e773eb593b0046452f420b6db8a47178c09e6db0fa68f6a2d42c3f48e3bc

SHA256 hashes of Windows EXE samples for INC ransomware:

- 02472036db9ec498ae565b344f099263f3218ecb785282150e8565d5cac92461

- 05e4f234a0f177949f375a56b1a875c9ca3d2bee97a2cb73fc2708914416c5a9

- 11cfd8e84704194ff9c56780858e9bbb9e82ff1b958149d74c43969d06ea10bd

- 1754c9973bac8260412e5ec34bf5156f5bb157aa797f95ff4fc905439b74357a

- 1a7c754ae1933338c740c807ec3dcf5e18e438356990761fdc2e75a2685ebf4a

- 29a25e971dbb87d3adcee75693782d978a3ca9f64df0a59b015ca519a4026c49

- 3156ee399296d55e56788b487701eb07fd5c49db04f80f5ab3dc5c4e3c071be0

- 36e3c83e50a19ad1048dab7814f3922631990578aab0790401bc67dbcc90a72e

- 508a644d552f237615d1504aa1628566fe0e752a5bc0c882fa72b3155c322cef

- 64b249eb3ab5993e7bcf5c0130e5f31cbd79dabdcad97268042780726e68533f

- 7f104a3dfda3a7fbdd9b910d00b0169328c5d2facc10dc17b4378612ffa82d51

- 869d6ae8c0568e40086fd817766a503bfe130c805748e7880704985890aca947

- 9ac550187c7c27a52c80e1c61def1d3d5e6dbae0e4eaeacf1a493908ffd3ec7d

- ca9d2440850b730ba03b3a4f410760961d15eb87e55ec502908d2546cd6f598c

- d147b202e98ce73802d7501366a036ea8993c4c06cdfc6921899efdd22d159c6

- e17c601551dfded76ab99a233957c5c4acf0229b46cd7fc2175ead7fe1e3d261

- ee1d8ac9fef147f0751000c38ca5d72feceeaae803049a2cd49dcce15223b720

- f96ecd567d9a05a6adb33f07880eebf1d6a8709512302e363377065ca8f98f56

- fcefe50ed02c8d315272a94f860451bfd3d86fa6ffac215e69dfa26a7a5deced

- fef674fce37d5de43a4d36e86b2c0851d738f110a0d48bae4b2dab4c6a2c373e

SHA256 hashes of Linux ELF samples for INC ransomware:

- 63e0d4e861048f581c9e5c64b28a053eb0023d58eebf2b943868d5f68a67a8b7

- a0ceb258924ef004fa4efeef4bc0a86012afdb858e855ed14f1bbd31ca2e42f5

- c41ab33986921c812c51e7a86bd3fd0691f5bba925fae612f1b717afaa2fe0ef

Contact email address from Lynx ransomware note:

- martina.lestariid1898@proton[.]me

Publicly accessible leak site blog for Lynx ransomware:

- lynxblog[.]net

Tor URLs for Lynx ransomware:

- http[:]//lynxbllrfr5262yvbgtqoyq76s7mpztcqkv6tjjxgpilpma7nyoeohyd[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxbllrfr5262yvbgtqoyq76s7mpztcqkv6tjjxgpilpma7nyoeohyd[.]onion/disclosures

- http[:]//lynxblogco7r37jt7p5wrmfxzqze7ghxw6rihzkqc455qluacwotciyd[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxblogijy4jfoblgix2klxmkbgee4leoeuge7qt4fpfkj4zbi2sjyd[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxblogmx3rbiwg3rpj4nds25hjsnrwkpxt5gaznetfikz4gz2csyad[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxblogoxllth4b46cfwlop5pfj4s7dyv37yuy7qn2ftan6gd72hsad[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxblogtwatfsrwj3oatpejwxk5bngqcd5f7s26iskagfu7ouaomjad[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxblogxstgzsarfyk2pvhdv45igghb4zmthnzmsipzeoduruz3xwqd[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxblogxutufossaeawlij3j3uikaloll5ko6grzhkwdclrjngrfoid[.]onion

- http[:]//lynxch2k5xi35j7hlbmwl7d6u2oz4vp2wqp6qkwol624cod3d6iqiyqd[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatbykq2vycvyrtjqb3yuj4ze2wvdubzr2u6b632trwvdbsgmyd[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatde4spv5x6xlwxf47jdo7wtwwgikdoeroxamphu3e7xx5doqd[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatdy3tgcuijsqofhssopcepirjfq2f4pvb5qd4un4dhqyxswqd[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatdykpoelffqlvcbtry6o7gxk3rs2aiagh7ddz5yfttd6quxqd[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatfw4rgsclp4567i4llkqjr2kltaumwwobxdik3qa2oorrknad[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatly4zludmhmi75jrwhycnoqvkxb4prohxmyzf4euf5gjxroad[.]onion/login

- http[:]//lynxchatohmppv6au67lloc2vs6chy7nya7dsu2hhs55mcjxp2joglad[.]onion/login

Additional References

- INC ransomware source code selling on hacking forums for $300,000 – Bleeping Computer

- INC Linux Ransomware - Sandboxing with ELFEN and Analysis – M&M: Malware and Musings by Nikhil "Kaido" Hegde

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh