Last week, PinnacleOne highlighted the flashpoint risk emerging at the near-term prospect of a full 2024-7-1 22:0:29 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:15 收藏

Last week, PinnacleOne highlighted the flashpoint risk emerging at the near-term prospect of a full-scale conflict between Israel and Hezbollah.

This week, we focus executive attention on the escalation dynamics in the South China Sea between China, Philippines, and the US, centered at the moment on the Second Thomas Shoal.

Please subscribe to read future issues — and forward this newsletter to interested colleagues.

Contact us directly with any comments or questions: [email protected]

Insight Focus | Flashpoint in Focus: South China Sea

China introduced its 9-dash line claiming most of the South China Sea in 1952. The 9-dash line traces the outline of the entirety of the sea, bordering Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines, and Taiwan. According to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) historians, the line is justified by the apparent (contested and invalid) control over the sea since early recorded history.

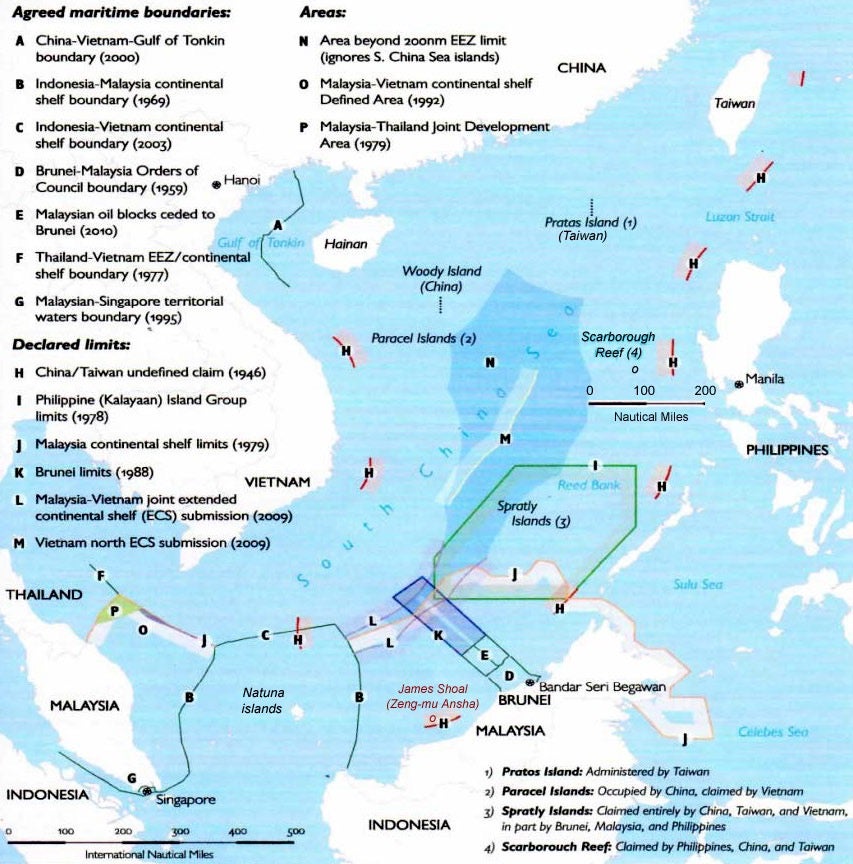

China’s claims fly in the face of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which is the current international framework defining sovereign claims over territory in the ocean adjacent to land. Under UNCLOS, there are many competing claims to territory in the South China Sea by all of its surrounding countries. The image below denotes just how many overlapping claims there are to the islands of the South China Sea, and just how far China’s 9-dash line trods over existing legal frameworks.

Islands (above water at all tides) can extend a country’s 200-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Rocks and reefs, which are partially submerged as the tides rise and fall, can extend the EEZ even further if they are within a short distance of islands, thus causing the EEZ to expand even further. China’s island-building efforts in the South China Sea are partially an effort to extend legality to their claims, although they also provide military bases, too.

In 1999, the Philippines ran aground the Sierra Madre on the Second Thomas Shoal. The vessel has since been home to a deployment of marines whose sole job is to maintain Filipino sovereignty over the landmass.

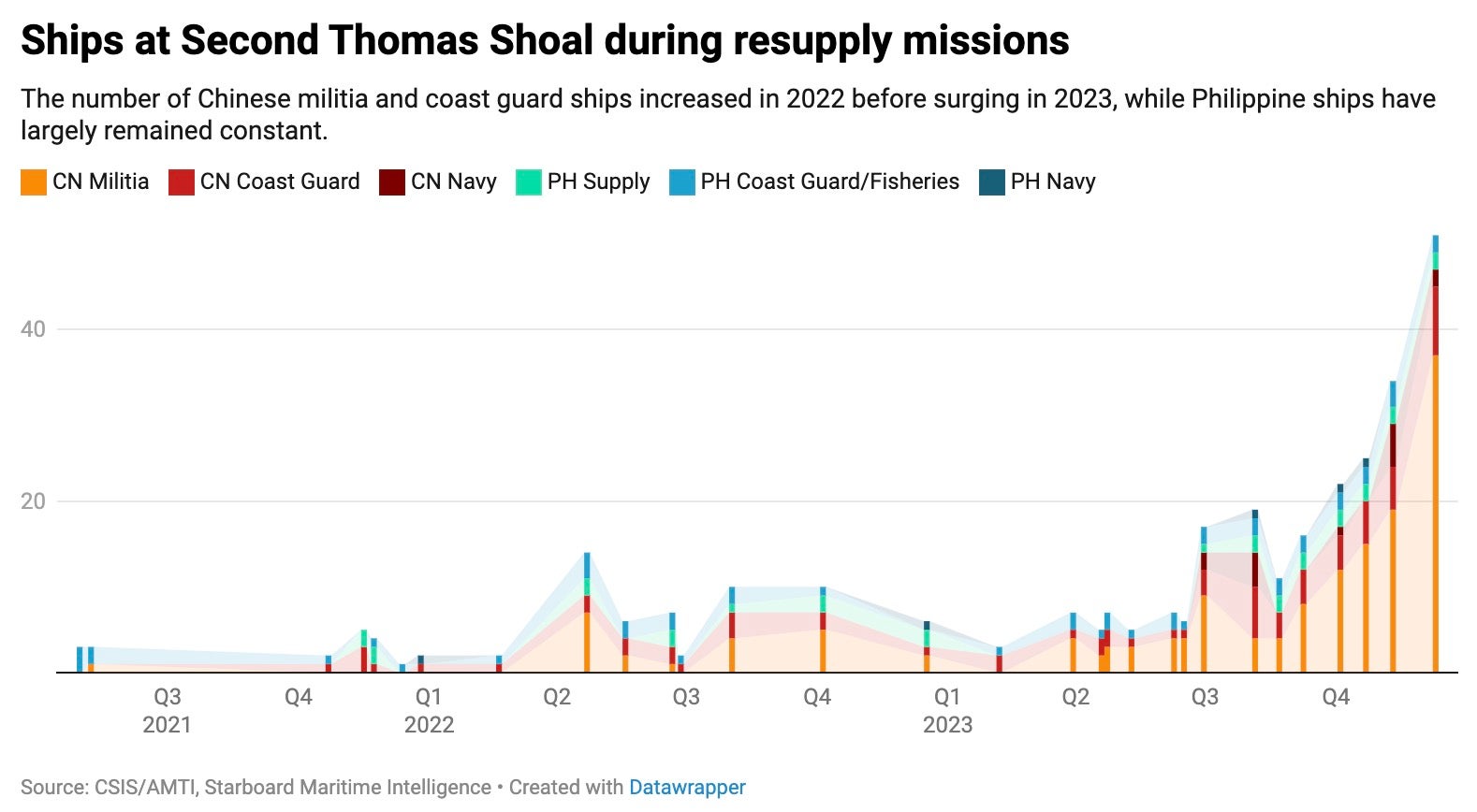

In recent months, tension over the Second Thomas Shoal has been at a fever pitch. Boats collide regularly. Chinese “fisherman” ram Filipino vessels or tangle nets in propellers. China’s Coast Guard stabs inflatable boats or blockades the Philippines from delivery food and supplies to the Sierra Madre. Two weeks ago, someone had a finger cut off between two colliding boats. This chart shows the number of ships present each time the Philippines tries to take items to its marines.

The tension is pushing governments to caution one another against further escalation.

“It’s the most dangerous time . . . weapons of mass destruction are very real. You have several countries, major powers that have large arsenals of nuclear power. If anything happens, the entire Asian region will be completely included.” – Jose Manuel Romualdez, Philippine Ambassador to Washington in a Financial Times interview.

The Financial Times asked Roumualdez “how a dispute over a reef could spark a major conflict” and he “used the example of the first world war, which was triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria.”

Further, US deputy secretary of state Kurt Campbell said the crisis could “spark conflicts that would devastate the global economy”.

Escalation Scenarios

Until last week, no one was quite sure why things had come to a head. At least, that was the case until the Financial Times reported that the Philippines had conducted a secret operation last year to reinforce the Sierra Madre as they feared its imminent collapse. The German Marshall Fund’s Bonnie Glaser noted that increasing tension around the vessel stems from China’s 25-year wait for the boat to collapse so that China could claim the Second Thomas Shoal as its own.

The United States and Philippines are subject to a mutual defense treaty, obliging each other to defend their partner in the event of war. The U.S. is putting immense pressure on the Filipino government to not use the mutual defense clause to force the US Navy to help resupply the Sierra Madre. When the PRC blockaded the ship in 2014, the Philippines daringly flew a helicopter over China’s boats. Now neither side seems averse to boat ramming, boarding, or potential fist fights between crew members.

If the boat is believed to soon collapse, both China and the Philippines are set on their objectives. China is on the cusp of winning a 25-year waiting game to claim an island near to the Philippines that would allow the PLA to station key military assets within striking distance of the island nation. The Philippines is holding onto an island in an attempt to stop it from becoming that military base. The U.S. is apparently just trying to avoid conflict.

Failure for either side is hard to stomach and that’s precisely why the risk of a crisis is so high.

Questions that no one can answer will decide the path of escalation or de-escalation for the Second Thomas Shoal: Will the Philippines ask for U.S. assistance? What happens if a sailor from either side dies? What if the boat suddenly collapses in an autumn typhoon? What if a ship is boarded by the Chinese and the Filipino sailors shoot them for doing so?

Implications for Businesses

Many mainstream media outlets are not appreciating the significant risk of the South China Sea at present. As a result, board rooms and CEOs are mulling over their Taiwan-risk scenarios with no thought to their operations in the Philippines, Malaysia, or Vietnam. All actors are incentivized to avoid armed conflict, so sub-kinetic attacks, like cyberattacks against critical infrastructure, ransomware operations against key businesses, and sabotage are all on the table. Companies with significant operations in the area should begin determining how to tighten their regional network security and operational posture.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh