2024-6-17 21:0:43 Author: securityboulevard.com(查看原文) 阅读量:6 收藏

By Max Ammann

Fuzzing—a testing technique that tries to find bugs by repeatedly executing test cases and mutating them—has traditionally been used to detect segmentation faults, buffer overflows, and other memory corruption vulnerabilities that are detectable through crashes. But it has additional uses you may not know about: given the right invariants, we can use it to find runtime errors and logical issues.

This blog post explains how Trail of Bits developed a fuzzing harness for Fuel Labs and used it to identify opcodes that charge too little gas in the Fuel VM, the platform on which Fuel smart contracts run. By implementing a similar fuzzing setup with carefully chosen invariants, you can catch crucial bugs in your smart contract platform.

How we developed a fuzzing harness and seed corpus

The Fuel VM had an existing fuzzer that used cargo-fuzz and libFuzzer. However, it had several downsides. First, it did not call internal contracts. Second, it was somewhat slow (~50 exec/s). Third, it used the arbitrary crate to generate random programs consisting of just vectors of Instructions.

We developed a fuzzing harness that allows the fuzzer to execute scripts that call internal contracts. The harness still uses cargo-fuzz to execute. However, we replaced libFuzzer with a shim provided by the LibAFL project. The LibAFL runtime allows executing test cases on multiple cores and increases the fuzzing performance to ~1,000 exec/s on an eight-core machine.

After analyzing the output of the Sway compiler, we noticed that plain data is interleaved with actual instructions in the compiler’s output. Thus, simple vectors of instructions do not accurately represent the output of the Sway compiler. But even worse, Sway compiler output could not be used as a seed corpus.

To address these issues, the fuzzer input had to be redesigned. The input to the fuzzer is now a byte vector that contains the script assembly, script data, and the assembly of a contract to be called. Each of these is separated by an arbitrarily chosen, 64-bit magic value (0x00ADBEEF5566CEAA). Because of this redesign, compiled Sway programs can be used as input to the seed corpus (i.e., as initial test cases). We used the examples from the Sway repository as initial input to speed up the fuzzing campaign.

The LibAFL-based fuzzer is implemented as a Rust binary with subcommands for generating seeds, executing test cases in isolation, collecting gas usage statistics of test cases, and actually executing the fuzzer. Its README includes instructions for running it. The source code for the fuzzer can be found in FuelLabs/fuel-vm#724.

Challenges encountered

During our audit, we had to overcome a number of challenges. These included the following:

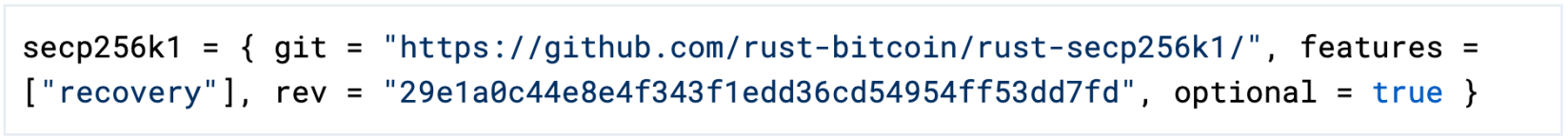

- The secp256k1 0.27.0 dependency is currently incompatible with

cargo-fuzzbecause it enables a special fuzzing mode automatically that breaks secp256k1’s functionality. We applied the following dependency declaration infuel-crypto/Cargo.toml:20:

Figure 1: Updated dependency declaration

- The LibAFL shim is not stable and is not yet part of any release. As a result, bugs are expected, but due to the performance improvements, it is still worthwhile to consider using it over the default fuzzer runtime.

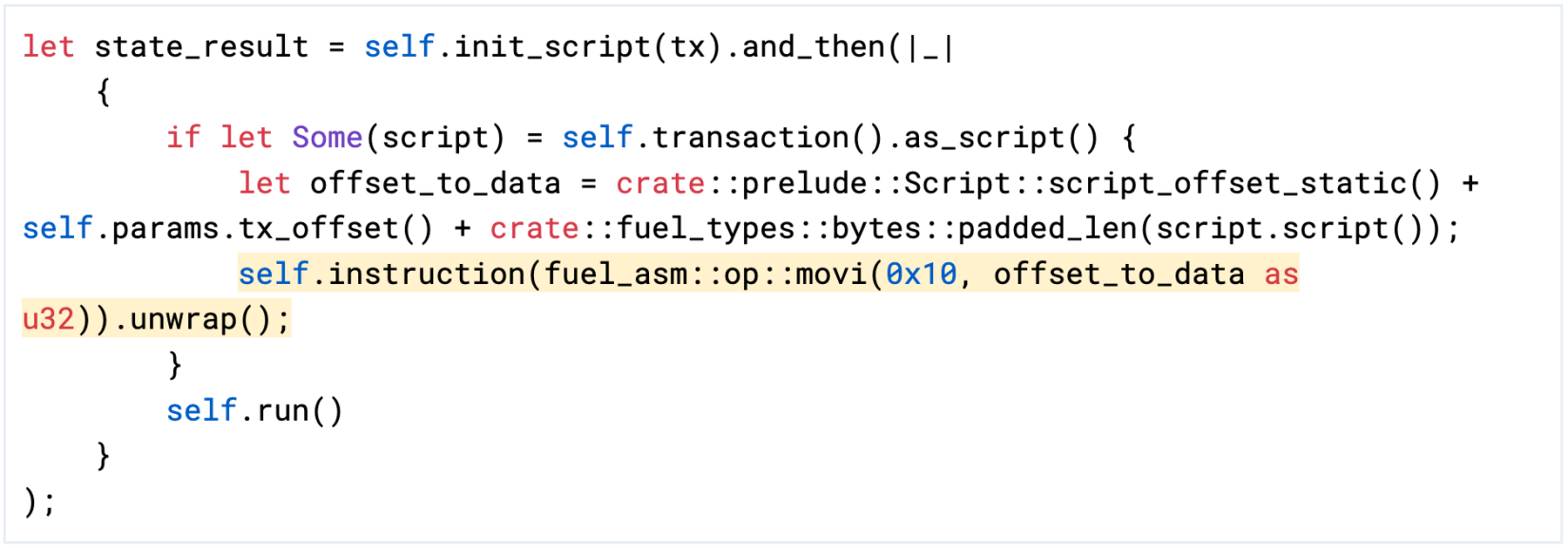

- We were looking for a way to pass in the offset to the script data to the program that is executed in the fuzzer. We decided to do this by patching the fuel-vm. The fuel-vm writes the offset into the register 0x10 before executing the actual program. That way, programs can reliably access the script data offset. Also, seed inputs continue to execute as expected. The following change was necessary in

fuel-vm/src/interpreter/executors/main.rs:523:

Figure 2: Write the script data offset to register 0x10

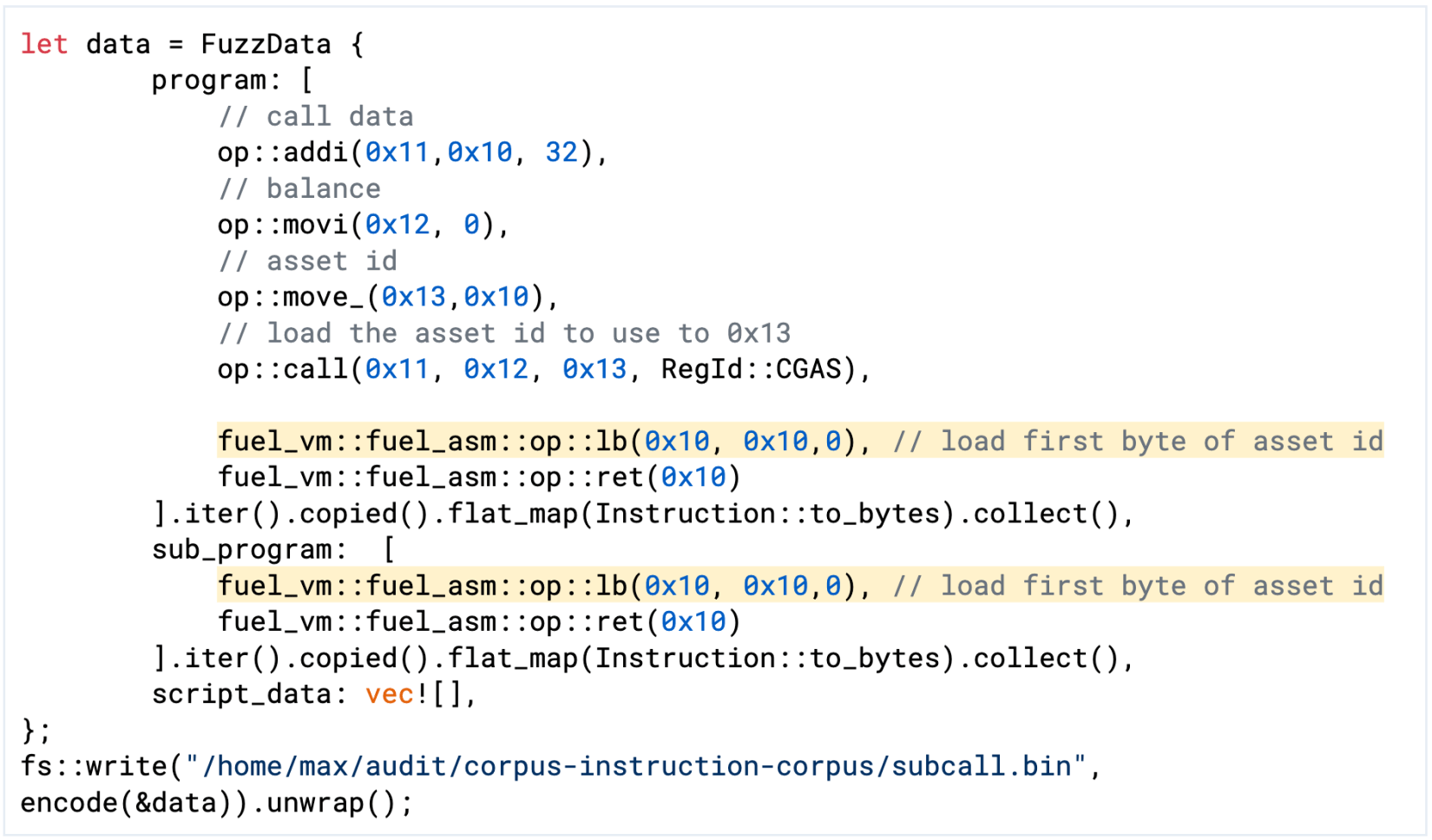

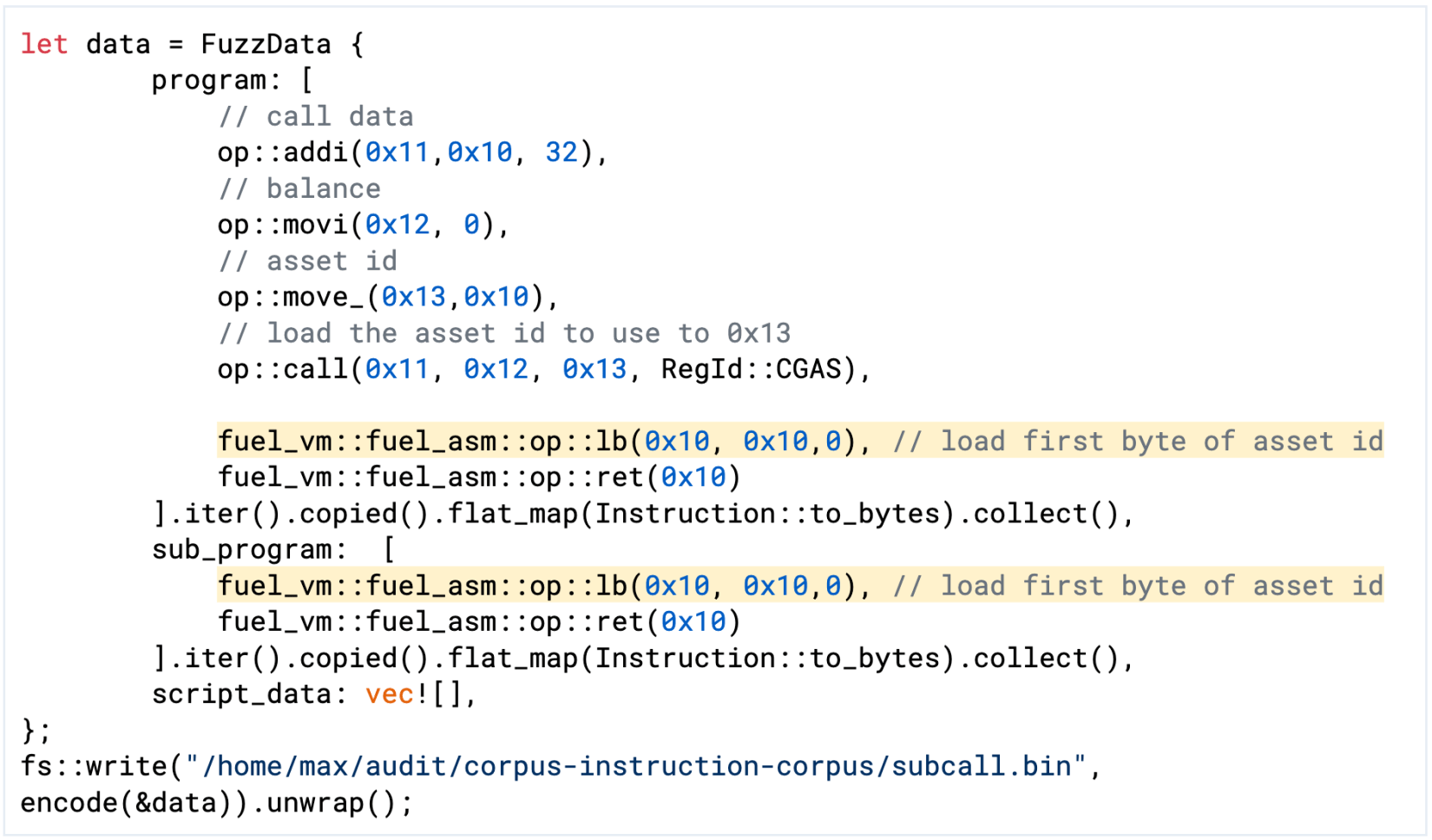

Additionally, we added the following test case to the seed corpus that uses this behavior.

Figure 3: Test case for using the now-available script data offset

Using fuzzing to analyze gas usage

The corpus created by a fuzzing campaign can be used to analyze the gas usage of assembly programs. It is expected that gas usage strongly correlates with execution time (note that execution time is a proxy for the amount of CPU cycles spent).

Our analysis of the Fuel VM’s gas usage consists of three steps:

- Launch a fuzzing campaign.

- Execute

cargo run --bin collect <file/dir>on the corpus, which yields agas_statistics.csvfile.- Examine and plot the result of the gathered data using the Python script from figure 4.

- Identify the outliers and execute the test cases in the corpus. During the execution, gather data about which instructions are executed and for how long.

- Examine the collected data by grouping it by instruction and reducing it to a table which shows which instructions cause high execution times.

This section describes each step in more detail.

Step 1: Fuzz

The cargo-fuzz tool will output the corpus in the directory corpus/grammar_aware. The fuzzer tries to find inputs that increase the coverage. Furthermore, the LibAFL fuzzer prefers short inputs that yield a long execution time. This goal is interesting because it could uncover operations that do not consume very much gas but spend a long time executing.

Step 2: Collect data and evaluate

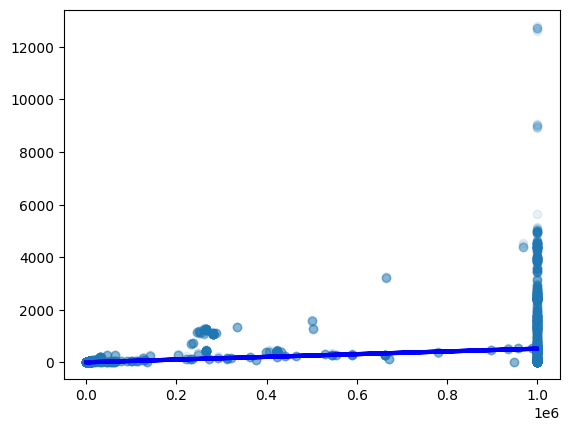

The Python script in figure 4 loads the CSV file created by invoking cargo run --bin collect <file/dir>. It then plots the execution time vs. gas consumption. This already reveals that there are some outliers that take longer to execute than other test cases while using the same amount of gas.

Figure 4: Python script to determine gas usage vs execution time of the discovered test inputs

Figure 5: Results of running the script in figure 4

Step 3: Identify and analyze outliers

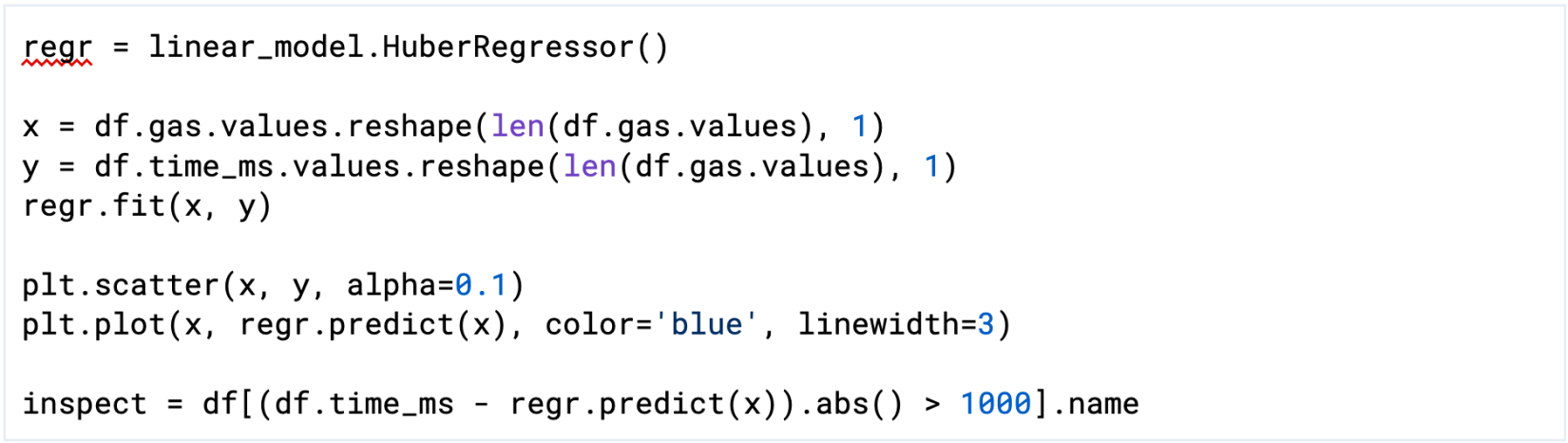

The Python script in figure 6 performs a linear regression through the data. Then, we determine which test cases are more than 1,000ms off from the regression and store them in the inspect variable. The results appear in figure 7.

Figure 6: Python script to perform linear regression over the test data

Figure 7: Results of running the script in figure 6

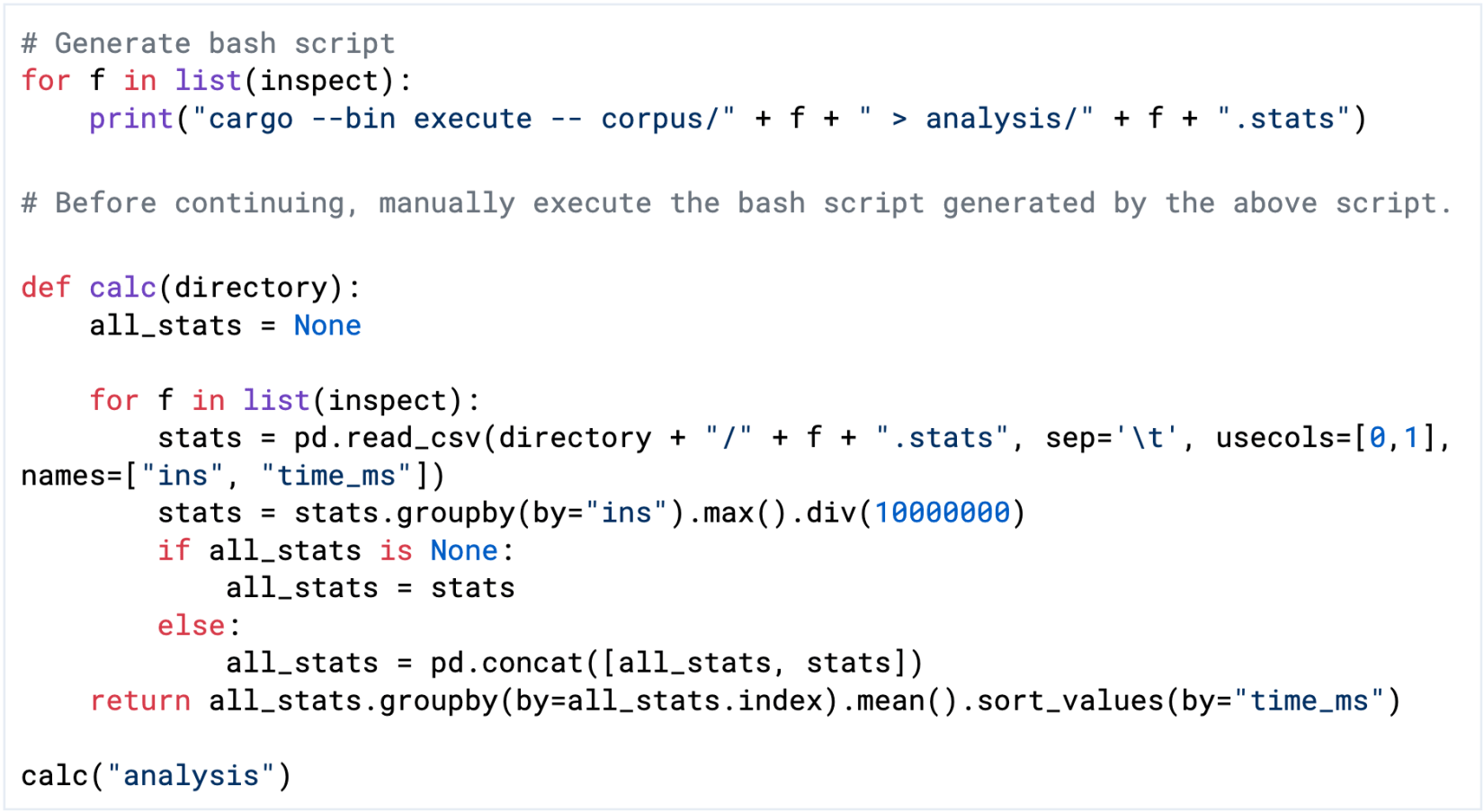

Finally, we re-execute the corpus with specific changes applied to gather data about which executions are responsible for the long execution. The changes are the following:

- Add

let start = Instant::now();at the beginning of functioninstruction_inner. - Add

println!("{:?}\t{:?}", instruction.opcode(), start.elapsed().as_nanos());at the end of the function.

These changes cause the execution of a test case to print out the opcode and the execution time of each instruction.

Figure 8: Investigation of the contribution to execution time for each instruction

The outputs for Fuel’s opcodes are shown below:

Figure 9: Results of running the script in figure 8

The above evaluation shows that the opcodes MCLI, SCWQ, K256, SWWQ, and SRWQ may be mispriced. For SCWQ, SWWQ, and K256, the results were expected because we already discovered problematic behavior through fuzzing. Each of these issues appears to be resolved (see FuelLabs/fuel-vm#537). This analysis also shows that there might be a pricing issue for SRWQ. We are unsure why MCLI shows in our analysis. This may be due to noise in our data, as we could not find an immediate issue with its implementation and pricing.

Lessons learned

As the project evolves, it is essential that the Fuel team continues running a fuzzing campaign on code that introduces new functionality, or on functions that handle untrusted data. We suggested the following to the Fuel team:

- Run the fuzzer for at least 72 hours (or ideally, a week). While there is currently no tooling to determine ideal execution time, the coverage data gives a good estimate about when to stop fuzzing. We saw no more valuable progress of the fuzzer after executing it more than 72 hours.

- Pause the fuzzing campaign whenever new issues are found. Developers should triage them, fix them, and then resume the fuzzing. This will reduce the effort needed during triage and issue deduplication.

- Fuzz test major releases of the Fuel VM, particularly after major changes. Fuzz testing should be integrated as part of the development process, and should not be conducted only once in a while.

Once the fuzzing procedure has been tuned to be fast and efficient, it should be properly integrated in the development cycle to catch bugs. We recommend the following procedure to integrate fuzzing using a CI system, for instance by using ClusterFuzzLite (see FuelLabs/fuel-vm#727):

- After the initial fuzzing campaign, save the corpus generated by every test.

- For every internal milestone, new feature, or public release, re-run the fuzzing campaign for at least 24 hours starting with each test’s current corpus.1

- Update the corpus with the new inputs generated.

Note that, over time, the corpus will come to represent thousands of CPU hours of refinement, and will be very valuable for guiding efficient code coverage during fuzz testing. An attacker could also use a corpus to quickly identify vulnerable code; this additional risk can be avoided by keeping fuzzing corpora in an access-controlled storage location rather than a public repository. Some CI systems allow maintainers to keep a cache to accelerate building and testing. The corpora could be included in such a cache, if they are not very large.

Future work

In the future, we recommended that Fuel expand the assertions used in the fuzzing harness, especially for the execution of blocks. For example, the assertions found in unit tests could serve as an inspiration for implementing additional checks that are evaluated during fuzzing.

Additionally, we encountered an issue with the required alignment of programs. Programs for the Fuel VM must be 32-bit aligned. The current fuzzer does not honor this alignment, and thus easily produces invalid programs, e.g., by inserting only one byte instead of four. This can be solved in the future by either using a grammar-based approach or adding custom mutations that honor the alignment.

Instead of performing the fuzzing in-house, one could use the oss-fuzz project, which performs automatic fuzzing campaigns with Google’s extensive testing infrastructure. oss-fuzz is free for widely used open-source software. We believe they would accept Fuel as another project.

On the plus side, Google provides all their infrastructure for free, and will notify project maintainers any time a change in the source code introduces a new issue. The received reports include essential important information such as minimized test cases and backtraces.

However, there are some downsides: If oss-fuzz discovers critical issues, Google employees will be the first to know, even before the Fuel project’s own developers. Google policy also requires the bug report to be made public after 90 days, which may or may not be in the best interests of Fuel. Weigh these benefits and risks when deciding whether to request Google’s free fuzzing resources.

If Trail of Bits can help you with fuzzing, please reach out!

1 For more on fuzz-driven development, see this CppCon 2017 talk by Kostya Serebryany of Google.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Trail of Bits Blog authored by Trail of Bits. Read the original post at: https://blog.trailofbits.com/2024/06/17/finding-mispriced-opcodes-with-fuzzing/

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh