2024-4-26 20:1:28 Author: therecord.media(查看原文) 阅读量:19 收藏

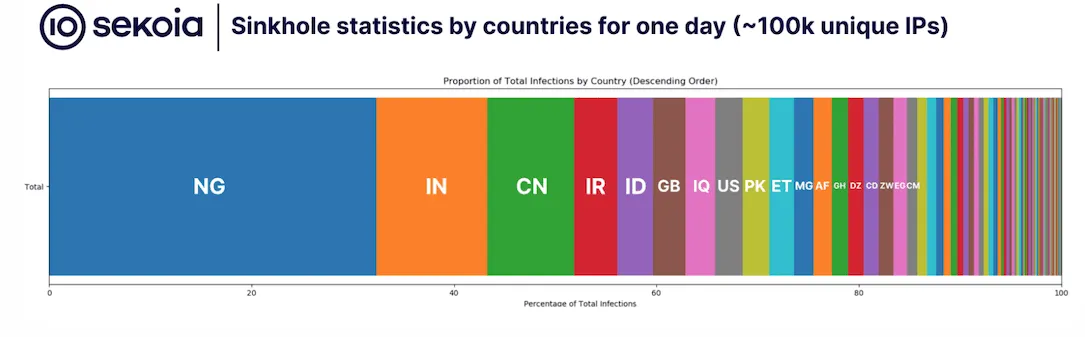

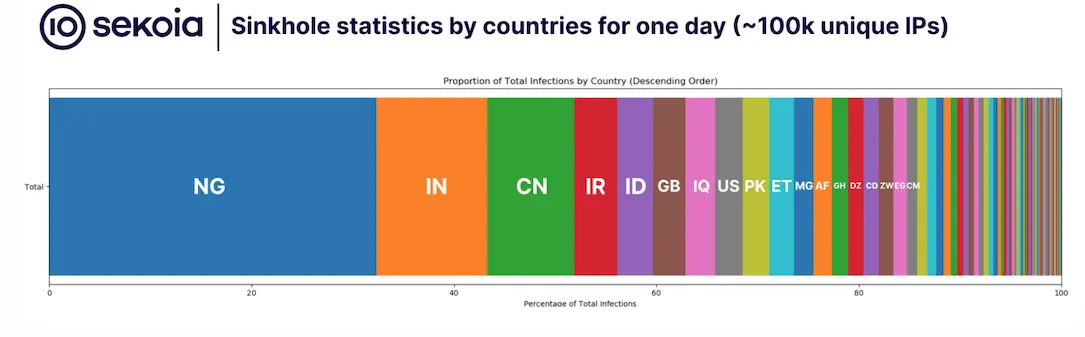

A strain of malware connected to the Chinese Ministry of State Security has been found in more than 170 countries, according to cybersecurity researchers who took control of a command and control server linked to it. Experts at cybersecurity firm Sekoia said they successfully took over the server in September 2023, giving them access to a trove of information about how far the PlugX malware has spread. The malware was initially developed by front companies linked to the Chinese agency in 2008 and has been used widely among the country’s espionage groups. In 2020, hackers within a group labeled Mustang Panda added a capability to the malware that allowed it to spread to connected USB flash drives — with the goal of gaining access to non-connected networks. Cybersecurity researchers at Sophos said last year that they saw “localized outbreaks” of a new variant of PlugX being spread through the USB drives in Mongolia, Zimbabwe and Nigeria after initial campaigns in Papua New Guinea and Ghana in January 2023. Sekoia’s team purchased the unique IP address tied to the variant identified by Sophos for $7 and found “between 90 to 100k unique IP addresses are sending PlugX distinctive requests every day.” “We initially thought that we will have a few thousand victims connected to it, as what we can have on our regular sinkholes. However, by setting up a simple web server we saw a continuous flow of HTTP requests varying through the time of the day,” Sekoia said. “We observed in 6 months of sinkholing more than 2.5 million unique IPs connecting to it.” Palo Alto Networks released a lengthy report on PlugX in 2021 and several companies have found it used in attacks on governments and companies around the world. In a one-day snapshot of PlugX activity, Sekoia found that around 15 countries account for over 80% of the total infections — led by Nigeria, India, Iran, Indonesia, the United States and more: Sekoia noted that the leading infected countries don’t share many similarities — suggesting the possibility that the malware “might have originated from multiple patient zeros in different countries.” “The geographical distribution of the most infected countries, as presented on the previous map, may indicate a possible motivation behind this worm. However, this must be taken with a grain of salt, because after four years of activities, it had time to spread everywhere,” they said. “Many nations, excluding India, are participants in China’s Belt and Road Initiative and have, for most of them, coastlines where Chinese infrastructure investments are significant. Analyzing the geographical distribution of the infections from a security perspective reveals that numerous affected countries are located in regions of strategic importance for the security of the Belt and Road Initiative – like the straits of Malacca, Hormuz, Beb-el-Mandeb or Plak.” The researchers said that while China invests everywhere, it is plausible that the malware was “developed to collect intelligence in various countries about the strategic and security concerns associated with the Belt and Road Initiative, mostly on its maritime and economic aspects.” Mustang Panda is also well-known for targeting the governments of countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiative. Sekoia eventually discovered that it was possible to send commands that would force the malware to destroy itself, disinfecting a system. But the researchers worried about the potential legal challenges that could arise from the kind of widespread disinfection campaign only law enforcement agencies like the FBI have embarked on. In the end, they decided to “defer the decision on whether to disinfect workstations in their respective countries to the discretion of national Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs), and cybersecurity authorities.” Those agencies can decide to remove the implant from the infected host, remotely if they so choose, Sekoia said. “Since some workstations located in one country can connect to the internet through another country (such as via VPNs or satellite internet providers), these authorities provide in return a list of autonomous systems that are OK to be disinfected,” they said. “Once in possession of the disinfection list, we can provide them an access to start the disinfection for a period of three months. During this time, any PlugX request from an Autonomous System marked for disinfection will be responded to with a removal command or a removal payload.” But the researchers noted that the malware can still exist on networks that are not connected to the internet and on infected USB devices.

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

Jonathan Greig

is a Breaking News Reporter at Recorded Future News. Jonathan has worked across the globe as a journalist since 2014. Before moving back to New York City, he worked for news outlets in South Africa, Jordan and Cambodia. He previously covered cybersecurity at ZDNet and TechRepublic.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh