2024-4-8 22:46:13 Author: therecord.media(查看原文) 阅读量:7 收藏

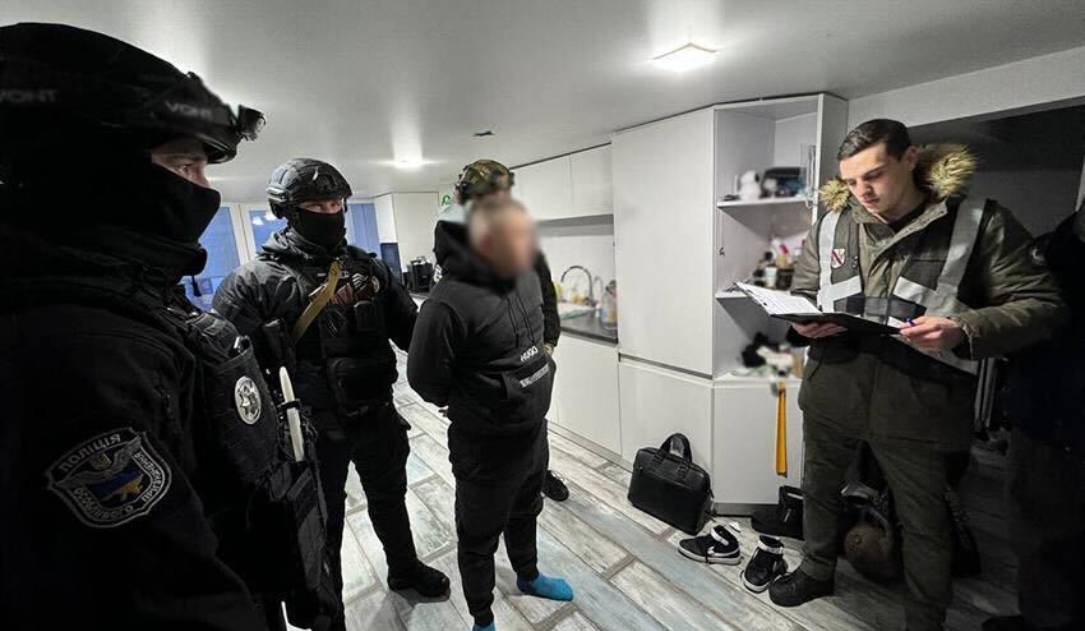

Officials in Westminster are being urged to put more money behind operations to disrupt ransomware gangs in the wake of a growing number of attacks impacting a wide range of services. The British government’s current focus for tackling the ransomware crisis — encouraging organizations to improve their cybersecurity, and to prepare to recover quickly if a compromise does occur — has not prevented incidents in the country from increasing year-on-year over the past five years. Recent victims have included the National Health Service, local government, social enterprises and numerous other organizations. This approach — which the government calls resilience — is the second pillar of the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Strategy. Despite a lack of measurable impact, officials consistently argued in support for more of the same during a recent parliamentary inquiry into the government’s response to ransomware. But concerns are growing that the government is neglecting to fund an alternative approach that has demonstrated better impact. Unlike in the United States, where the second pillar of that country’s National Cyber Strategy commits to disrupting criminal groups — and where the Department of Justice received a funding boost to do so — the British government has provided no new money in support of these disruption campaigns. With the limited funding available, some law enforcement activity has taken place. The National Crime Agency (NCA) earlier this year led an international operation to disrupt the LockBit ransomware-as-a-service gang, estimated to have accounted for 25% of all attacks globally before the operation effectively dismantled the gang’s core infrastructure. At a press event in London, the NCA director-general, Graeme Biggar, acknowledged: “If we had more resources, we’d be able to do more.” Lord Dannatt, the former head of the British Army and a member of the parliamentary committee which held the ransomware inquiry, is among those calling for a more proactive approach. The inquiry reported that because of the government’s failures to tackle ransomware, there is a “high risk” the country faces a “catastrophic ransomware attack at any moment.” Lord Dannatt told Recorded Future News that “campaigning on the forward foot, becoming more offensive and putting more effort into disrupting” would “start to get us out of the problem rather than just absorbing the punches.” During his witness testimony, the NCA’s Biggar acknowledged there had been “long debates” about the balance between the resilience and disrupt approaches. It was not an explicit criticism of where the government has currently set that balance, but the remark remains one of the few public statements from a senior official tasked with responding to the ransomware crisis about how that response is being managed by Westminster. Biggar told the inquiry there had been “a significant increase in cyber funding over the last 10 to 12 years.” To-date, the vast majority of this has gone into resilience. The principal argument for prioritizing resilience comes from a longstanding British approach to risk management. For officials at the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) — who define cyber risk as a combination of Threat, Vulnerability, and Impact — the argument is that it is impossible to reduce the threat to zero because there always have been and always will be people motivated to commit crime, while reducing vulnerability and reducing impact are both resilience tasks. But there is a growing belief that this model undervalues the ability for law enforcement to tackle the threat. Asked explicitly during the ransomware inquiry whether the NCA's National Cyber Crime Unit (NCCU) has the resources it needs, the security minister Tom Tugendhat said: “I am not going to have this debate in public,” and indicated that the allocation of resources to tackle ransomware was being spread throughout various parts of government. Lindy Cameron, then the NCSC’s chief executive, who sat beside Tugendhat during the witness session, added that “as much as we really value our partnership with the NCCU, and with the NCA in general, the real focus for us is driving up resilience.” She explained her preference was “to see more effort on the resilience end to make sure that we can help people to prepare, rather than simply focusing on what to do once we have seen this.” “Particularly in the context of ransomware, we are certainly not going to arrest our way out of this problem,” said Cameron. The ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline in 2021 caused oil and gas disruptions along much of the Southeastern U.S. Image: Colonial Pipeline Arrests are generally not the expected outcome of law enforcement disruptions. The NCA defines disruptions as operations leading to a criminal organization being “unable to operate at usual levels of activity.” Charles Carmakal, the chief technology officer at cybersecurity company Mandiant, is among those who believe the effectiveness of these disruptions at reducing the threat has potentially been underappreciated. Carmakal recalled what he considered to be the worst series of cyberattacks against the United States, beginning in October 2020 with a spate of ransomware incidents against healthcare providers, forcing ambulances to be diverted to neighboring hospitals and patients to be transferred from their beds due to the ongoing obstructions to care. A few months later an attack on Colonial Pipeline caused fuel shortages across the Southeastern United States, and then a supply-chain incident affecting Kaseya ultimately impacted more than 1,500 other downstream organizations. “When you look at that time period, between October 2020 and summer 2021, you’d argue that we were dealing with probably the worst series of cyberattacks,” Carmakal told Recorded Future News, “and it felt like things were only going to get worse.” Law enforcement officials told Recorded Future News that it was during this period they began to realize that treating ransomware like a traditional criminal threat was unsustainable. There were too many individual strains to investigate each as a separate organized crime group — a doctrinal change was needed. This change was rooted in the officials recognizing that the ransomware ecosystem was at its core a method of monetizing software vulnerabilities; that the threat was fundamentally a business model. While business models can’t be arrested, they can be disrupted. Instead of getting worse as Carmakal feared, a number of “really interesting law enforcement actions” took place to go after that business model. “Number one, we saw about half of the money that Colonial Pipeline had paid to the threat actors be essentially reclaimed by law enforcement,” said Carmakal. “Number two, we saw victims of the Kaseya incident end up getting a decryptor for free, enabling them to recover their systems and their data. We started seeing a lot of arrests and indictments of a number of criminal operators, we saw infrastructure that ended up getting seized by global law enforcement agencies.” While “the first half of 2021 felt like it was the worst time, from an overall security perspective because of how significant the threats were, the second half actually felt like we were kind of starting to win from a defensive perspective, because of all the law enforcement actions that had taken place.” And then, said Carmakal, it seemed the number of attacks started to go down. Ukrainian police arresting a cybercriminal in January. Image: National Police of Ukraine Some analysts attributed a drop in ransomware attacks for a period in 2022 to the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on the cybercrime ecosystem. Carmakal suggested that the drop began before then, and that the escalation in law enforcement disruptions in the preceding months may have been the more significant factor. In the second half of 2021, Mandiant observed a number of threat actors begin to recognise the potential costs they faced as a result of the FBI’s response to the Colonial and Kasya incidents. “Many of these folks have families, kids, wives, they don’t want to go to jail, and they don’t want to ruin their lives. There were a number of people that were seriously considering whether this was the path they wanted to continue to go down, because there was a real fear of repercussions,” said Carmakal. “There were certain things that we saw occur, we saw a slowdown in ransomware for some period of time — you could argue what the reason was for that, was it because they were getting arrested, was it because there was more of a focus on the Russia-Ukraine situation, but there were some real risks of repercussions.” But, said Carmakal, that sense of risk diminished. The lack of major ransomware disruptions in 2022 may have helped the criminals rediscover their confidence. During that period, as the war in Ukraine raged on, ransomware attacks surged to record levels. “Fortunately over the past few months, we’ve seen some pretty major actions,” he added, noting operations against the AlphV/BlackCat group and Ragnar Locker. Carmakal particularly praised the LockBit disruption in February as “a very British takedown when you look at the trolling that was done, it was honestly just kind of hilarious.” Following the seizure of the LockBit darknet site, the NCA hijacked that site to display information about the gang and its affiliates instead of about LockBit’s victims. It was a new tactic that emphasized the intelligence captured by the law enforcement operation for the sake of undermining confidence in the ransomware gang. “I think it's true that every time there's been a technical disruption, even if the group has sort of bounced back, they have ultimately disappeared,” said Rafe Pilling, the director of threat research at the Secureworks Counter Threat Unit. “We know that these groups reform and come back with another product and another brand in many cases, but there's always that intervening period where people are not getting ransomed due to those operations, and that's always a win,” Pilling added. And beyond the individual impact on specific groups or brands, “the cumulative impact of multiple disruption operations against these different ransomware brands is beginning to undermine some of the confidence and credibility in and amongst these groups,” said the Secureworks director. Caramel said: “I look forward to more and more of these announcements, because sometimes actions occur, arrests occur, but the indictments don’t get unsealed for many months, and so nobody really knows that law enforcement has all these wins. What will inevitably happen over time is that the threat actors will start to feel like there are actually some real risks or repercussions… When there’s fear by threat actors, it will curb the problem to some extent.” The NCA’s head of cyber intelligence, Will Lyne, told Recorded Future News the agency worked hard to understand the impact of its operations and used those lessons to develop future tactics. “We do note the current turmoil within the ransomware ecosystem, but it is too early to make a formal judgement around the LockBit disruption, and there is more activity to come as the investigation continues,” he said. When the NCSC was founded back in 2016, the government stated its aim was to make the United Kingdom “the safest place to live and work online.” Nobody could argue that aim has been achieved. By some measurements, the United Kingdom has more cybercrime victims per million internet users than anywhere else in the world. Advocates of the resilience approach point out that it reduces the vulnerability and impact of far more types of malicious cyber activity than just ransomware — a single type of threat that is estimated to account for fewer financial losses than incidents of business email compromise, in which criminals hijack a legitimate email thread to send fraudulent invoice account details. But beyond the pecuniary damage from the extortion itself, there are less measurable impacts from ransomware attacks including the distress caused to individuals affected by the publication of stolen data, and the distress for those who suffer incidents at their own organizations. The potential impact of an attack on critical national infrastructure or a surprisingly important part of commercial supply-chains — such as cold storage and refrigerated transport firm Reed Boardall, which is responsible for moving a significant amount of the country’s frozen food — means British officials continue to regard ransomware as a national security threat. One of the most commonly proposed solutions to that threat is to remove the motivation for criminals by banning victims from making payments. Ciaran Martin, the former head of the NCSC, recently complained that governments have not done enough formal analysis on such a ban. But the idea has been repeatedly discussed by officials in the United States and United Kingdom. As previously reported by Recorded Future News, back in 2021 the British government held a cross-Whitehall “sprint” — a project management term — that concluded a ban on ransomware payments would not be workable. Those working in law enforcement and for intelligence agencies say it is a mark of the strength of the ransomware ecosystem that making such a payment is sometimes the least harmful option available to a victim. Law enforcement officials further caution that preventing payments could also be the most expensive response to the problem, arguing that the limited resources available to tackle ransomware would be best deployed against the perpetrators themselves rather than against the victims. In the United Kingdom payments are prohibited against a few sanctioned ransomware actors, but as Recorded Future News has reported, no attempted payments to one of these entities has ever been detected. The key function of the sanctions isn’t really to prevent victims from making an extortion payment, instead they’re used as a disruption tool prized for “sowing discord within certain groups.” A ransomware ban is in some ways the epitome of what Lord Dannatt described as the “absorbing the punches” approach. It assumes that due to a lack of payment, criminals would eventually focus their attention on other territories. However it is not clear how long the intermediate phase would last of organizations in Britain being attacked before the ransomware gangs looked elsewhere. During this period, when victims in the country didn’t have recourse to that “least harmful option” of making an extortion payment, the country would incur additional costs due to businesses being interrupted. The negligible expense of conducting a ransomware attack provides the criminal ecosystem with a significant asymmetric advantage. The point, say officials, is to find a course of action that delivers such an advantage against the ransomware gangs rather than amplify what is already working so well for them. Officials at a London briefing following the takedown of the LockBit ransomware gang. Image: Alexander Martin / Recorded Future News Today law enforcement’s efforts are focusing on the business model’s weak points; hitting the links in the chain that could have cascading effects — from seizures of bulletproof hosting providers such as LolekHosted through to operations targeting the individuals who code effective encryption software. These people are as precious a resource in the ransomware world as they are in legitimate industry. Cryptography is a challenging technical task even for large commercial enterprises and so the individuals who can develop software to encrypt victims’ systems without using so much CPU power as to give the game away — and who can create an effective mechanism for managing the keys — are highly valued in the cybercrime ecosystem, with most of them serving multiple different groups. For the proponents of disruption, the cross-cutting effects are about even more than just the asymmetric battle against ransomware gangs — they’re about meeting some of the aims that the resilience approach wants to address too. One of the major challenges facing policymakers in the ransomware space is the issue of underreporting — of organizations not coming forward after being attacked. A number of initiatives have been proposed to address this, including Britain’s data protection regulator pledging to take into account whether a victim had contacted the NCSC when determining if a fine was appropriate for a breach. This is an incentive to report, but officials say it is not a motivation — unlike knowing that law enforcement has repeatedly secretly acquired decryption keys from ransomware groups and quietly shared them with victims to help them recover. The NCA’s Lyne said his agency “working closely with our national and international partners, initially obtained over 1,000 decryption keys relating to LockBit victims. Subsequent analysis on the data we obtained from LockBit’s systems has enabled us to increase the number of decryption keys to several thousand, and our work continues to offer support and assistance to victims in the UK and overseas. “LockBit is not the first and will not be the last ransomware variant to be disrupted by law enforcement, and those victims that reported and engaged with law enforcement were the ones we were best able to assist,” Lyne added. “We encourage all UK-based victims of ransomware to use the Government’s Cyber Incident Signposting Site as soon as possible for direction on which agencies to report your incident to.” Dame Margaret Beckett MP, the chair of the Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy which held the ransomware inquiry, accused the government of taking the “ostrich strategy” by burying its head in the sand over the “large and imminent” national cyber threat posed by ransomware. The committee has expressed its “ongoing, deep concerns” that the government’s “short-termism and lack of preparation and planning” was risking “a severely damaging ransomware attack - with consequences that vary from ongoing damage to the economy and productivity to the real possibility of a national emergency.” “The UK is and will remain exposed and unprepared if [the government] continues this approach to tackling ransomware,” warned Beckett. Lord Dannatt told Recorded Future News that “disruption, going on the offensive, actually has got a lot to be said for it,” while he described resilience as “rather passive,” and compared the lack of investment in disruption activities to the government’s lack of investment in real-terms in defense — something against the trend among NATO allies which the former Chief of Staff previously criticized given the ongoing war in Europe. “If the first duty of government is to protect the territory of its own country, and its citizens both at home and abroad, there is a case to say that we should be allocating more money on defense in the round and therefore by extension into our cybersecurity.” In response to a full list of statements included in this story, a government spokesperson said: “Tackling ransomware is a key priority for the government, and we stand well prepared to respond to cyber threats. “The world’s most harmful cyber and ransomware group, LockBit, was recently disrupted by our joint international campaign and last year we took down a piece of malware that infected 700,000 computers,” they said, referencing the FBI-led operation to tackle Qakbot. “Through a further £2.6bn investment, our National Cyber Strategy will continue to tackle ransomware and cybercrime firsthand to continue protecting UK businesses and organisations,” they added. The spokesperson’s statement did not indicate how much of this investment would be apportioned to disruption operations. The same, but moreso?

Does disruption work?

Did we give Russia law enforcement’s credit?

Absorbing the punches

Cross-cutting effects

Government short-sightedness

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and is also a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh