Israel’s continued offensive has ravaged Gaza. It has polluted the soil, water and a 2024-3-16 05:32:30 Author: www.bellingcat.com(查看原文) 阅读量:17 收藏

Israel’s continued offensive has ravaged Gaza. It has polluted the soil, water and air, compounding a humanitarian crisis which the UN recently characterised as “imminent famine”. Reuters recently reported that starving civilians had resorted to eating the leaves of prickly pear cactuses to stave off hunger.

Such acts mean that, while Gaza’s environment is a cause for concern for ecologists, the territory’s flora can also show a great deal about its desperate humanitarian situation.

On February 29, the Union of Gaza Strip Municipalities issued a statement saying that Gaza Strip communities had not received fuel deliveries since October, a fact that was causing a cascading effect across all sectors of society and leading to “great suffering.” These acute fuel shortages have led civilians to cut down trees in order to start fires for cooking or warmth. In a food security report from December 2023, the World Food Programme stated that 70 percent of internally displaced people (IDPs) in southern Gaza burn firewood for fuel and 13 percent waste products.

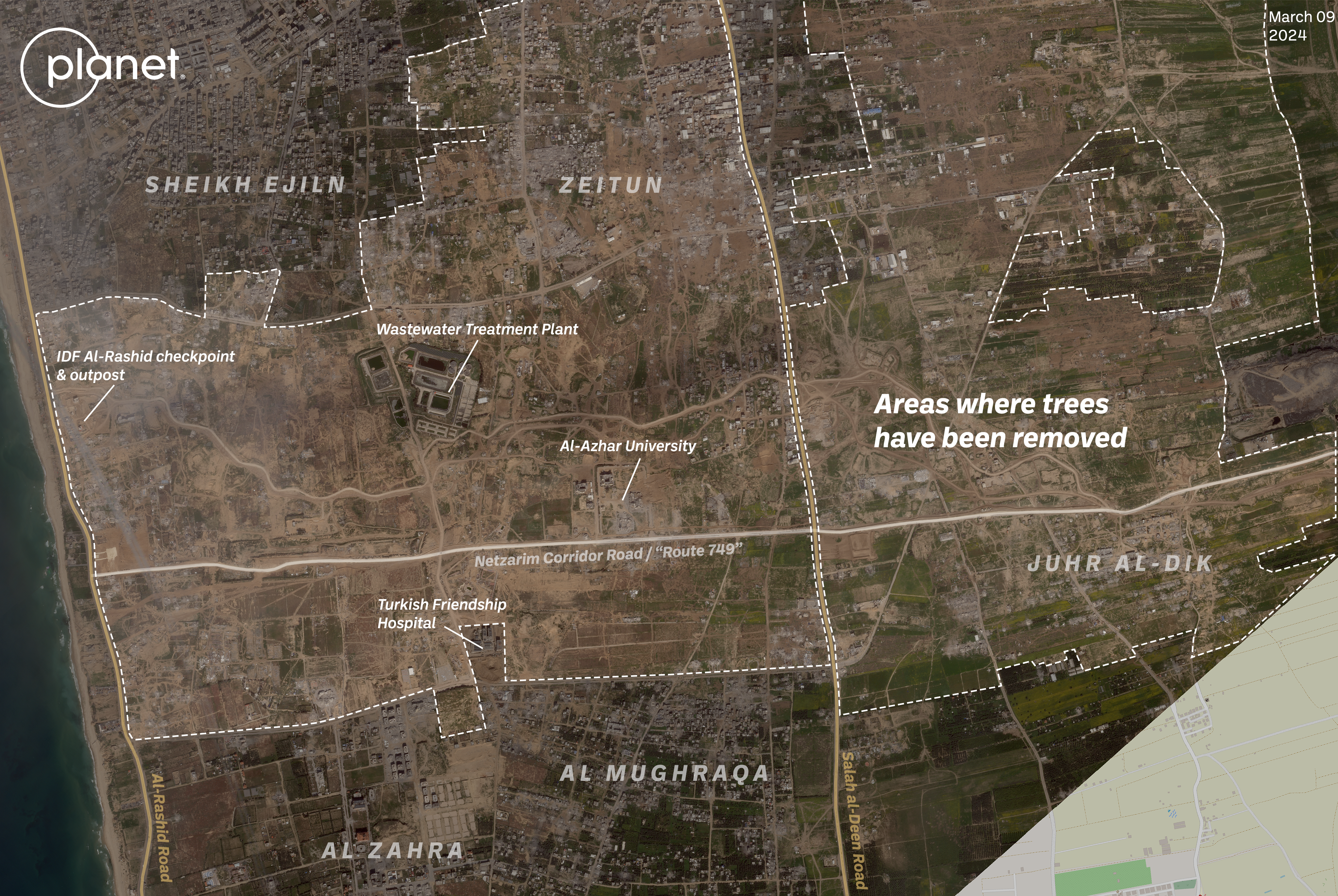

Bellingcat’s analysis of satellite imagery from Gaza, conducted with our partners at Scripps News, shows clear signs of the mass removal of trees which intensified in the winter months. These areas include cemeteries, parks and a university campus.

Importantly, satellite imagery shows that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have removed significant numbers of trees for stated military purposes, though more often in orchards and farmland. These cases can often be distinguished by the presence of vehicle tracks; the relative absence of vehicle tracks when done by Palestinian civilians is a tell-tale sign of the fuel shortages which drives them to such desperate measures.

Acts of Destruction

In contrast to the deforestation of necessity caused by civilian activities like the collection of food and fuel, the Israeli military is deforesting Gaza and destroying agricultural land as part of its ongoing incursion.

Olives are an important crop for Palestinian farmers; orchards can not only be found in the West Bank but also near Khan Younis and elsewhere in the Gaza Strip. The tree is of particular cultural significance to Palestinans.

Since October 2023, Israeli officials have incrementally revealed their plans for Gaza after the end of their military operation there. In January they spoke of the creation of a “buffer zone” on the border between Israel and the Gaza Strip that will be “more than double” its size before October 7, the date of the Hamas attack on Israel.

Israeli media has reported that this new buffer zone “consists mostly of agricultural areas”, and that the IDF was in the process of demolishing buildings in the zone as of late January.

Satellite imagery from Planet Labs shows vast areas of the Gaza Strip where the IDF has operated has been cleared of orchards and farmland. One of these areas is the so-called “Netzarim Corridor” — a strip of land bisecting the Gaza Strip just south of Gaza City. The corridor was detailed in a segment aired by Israel’s Channel 14 in February.

Following what the IDF call “Route 749”, the Netzarim Corridor will reportedly remain under Israeli control for months, if not longer, and allow the IDF to conduct raids or operations into Gaza.

Satellite imagery from March 9, when compared with imagery from October 15, shows that the area within this corridor has been heavily deforested with more than roughly 4,300 acres of land cleared of trees and other plant life. This number was measured using QGIS in-program measuring tool to calculate the areas of cleared locations visible in March 9 visual satellite imagery from Planet Labs along the Netzarim Corridor.

The image below shows the appearance of heavy vehicle tracks in this area in more detail:

This isn’t a unique location. A December investigation from Human Rights Watch found orchards, greenhouses and farmland north of the city of Beit Hanoun was razed by the IDF. This continued during a military pause in fighting in November.

Ahmed Benchemsi, the Communications Director for the Middle East and North Africa Region at Human Rights Watch, told Bellingcat, “The law or the laws of war are clear. Warring parties are strictly prohibited from attacking objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population and objects. … It means food, it means medical supplies, it means drinking water installations. And it means agricultural areas, which have been very widely destroyed by the Israeli army.”

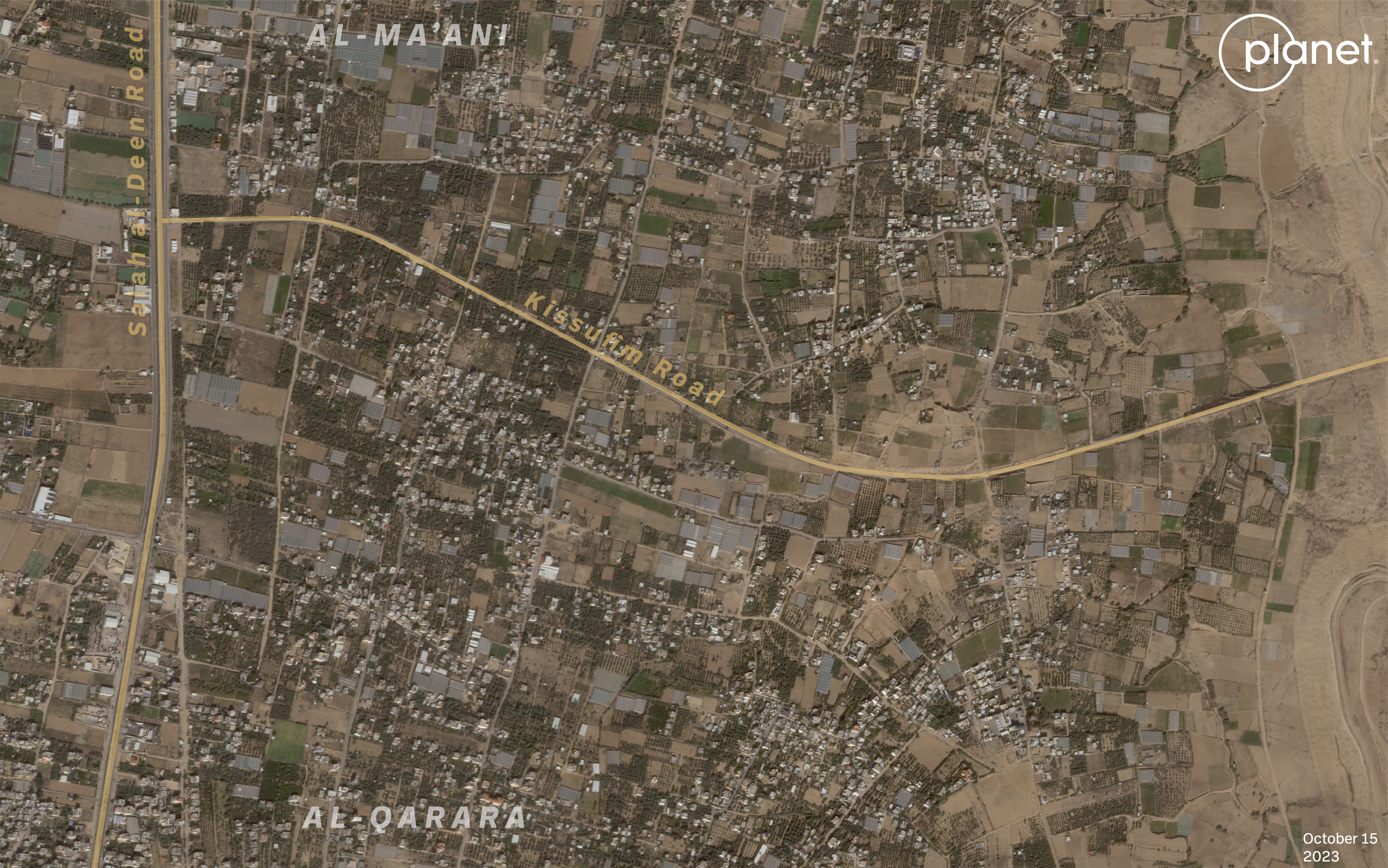

An analysis of January 19 Planet Labs satellite imagery shows a similar level of clearing in southern Gaza along Kissufim Road. An IDF military presence on the ground in this area was reported by Israeli media in late January. Using the measurement tool in QGIS, the total acreage of cleared land for this area comes out to be around 805 acres.

Additionally, March 2 imagery from Planet Labs shows large tracts of orchards and agricultural land have been cleared in Central Gaza, near the fertile Wadi Gaza just east of Al-Maghazi and Al-Bureij. In all, around 1,287 acres were visibly cleared in this area.

In an interview with The New York Times in a January story, the IDF told the reporter that orchards near Al-Bureij were levelled over concerns there could be landmines buried among the trees.

“I don’t come for revenge, I come because it’s necessary,” a general told the Times reporter.

Acts of Desparation

Another cause of deforestation in Gaza is the desperate humanitarian situation caused by Israel’s military operations.

An illustrative example can be seen in Deir Al-Balah, a town in the centre of the Gaza Strip. In June 2023, satellite imagery showed extensive tree cover in a cemetery (31.4168018, 34.3505251) wedged between two large streets and a mosque.

By November 5, we see the first signs of trees disappearing. By November 21, this had accelerated and only a few trees cast shadows over the now mostly bare cemetery, with a small concentration remaining in the south of the cemetery.

By January 7, the latest date for which Planet Satellite imagery is available, this cluster of trees has mostly disappeared. The shadows cast by trees, sometimes more visible in satellite imagery than the tree itself, have vanished.

A video recorded by the Palestinian Wafa News Agency in mid-November last year explains the cause: it shows young men chopping down the remaining trees in the cemetery. Their cause for doing so may explain the accelerated rate in subsequent months. In December 2023 civilian buildings in Deir Al-Balah were attacked in an Israeli airstrike.

A cemetery further north in Deir Al-Balah (31.4216389, 34.3545) shows similar change over time.

Trees appear to be present at the cemetery at least till early November but a satellite image from November 21 shows a majority of them chopped down. Vehicle tracks- usually visible when the IDF clears an area- are absent in these satellite images, possibly indicating that the trees were removed by civilians.

Tent camps are also visible on the right of the cemetery. As the tents expand, more trees seem to disappear along the perimeter of the cemetery. This is visible in a December 31 satellite image.

On December 5, 2023, the Israeli military reportedly advanced south into Khan Yunis, a city overwhelmed by people fleeing the northern areas of the Gaza Strip.

Vehicle tracks are absent in a cemetery in the west of Khan Yunis (31.3427629,34.2866418) that lost its trees by November 26 — a sign that the vegetation was likely removed by displaced Gazans for firewood or supplies. Satellite imagery captured on February 17 later shows the cemetery almost completely bare. Tread marks and craters in and around the cemetery indicate it may have been damaged in an Israeli offensive.

Asda’a City, a sprawling outdoor complex in Khan Yunis featuring a water park (31.3733756,34.2977551), underwent a gradual loss of its trees starting in December. Satellite imagery from January 15 shows the park almost completely bare.

Last month, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced an offensive in the southernmost city of Rafah which sits on the border with Egypt. Netanyahu claimed that it is “Hamas’s last bastion”. The announcement drew criticism from human rights groups as a majority of Palestinians, over one million, are living in tent camps in Rafah after Israel issued repeated directives to find refuge in the city.

One of the largest UNRWA shelters, Khan Younis Training Centre, was located just south of the Asda’a City. According to UNRWA, 43,000 internally displaced people were registered in the “massively overcrowded” shelter by late January.

Trees appear to have been cleared in cemeteries in Rafah — a change visible within just a few days at a cemetery in the west (31.2828852, 34.2589362). Satellite images captured on December 2 depict trees that disappeared by December 6.

A cemetery in eastern Rafah (31.2678574, 34.2591834) also shows the disappearance of trees — vehicle tread marks are not visible in both cases.

Trees are not only felled for firewood but also to clear the land for temporary shelters.

Desperate conditions have forced civilians to live in tents “built with flimsy material” in Rafah, said Human Rights Watch (HRW) on February 9. Some of these encampments are on farmlands. Trees bordering the southern end near Egypt (31.3205375, 34.2190991), close to the village of Al Qarya as Suwaydiya, were removed as shelters have spawned in the vicinity.

An aerial view of the area weeks after the start of the violence and satellite imagery from February show a stark difference in the vegetation.

Similar deforestation was earlier observed north of Rafah – in urban areas of Khan Yunis, the second biggest city in Gaza. Since mid-October, makeshift tents were being built on the grounds of Nasser Hospital in Khan Yunis (31.347592, 34.2915739). As the tents progressively grew with Israel expanding airstrikes, satellite imagery from mid to late December shows palm trees in the hospital complex removed to build tents and create space for those taking shelter.

However, after Israeli forces pushed deeper into Khan Yunis, the tents in the hospital complex gradually disappeared. The complex was later bombed.

“Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis, Gaza, was shelled in the early hours of this morning, despite Israeli forces having told medical staff and patients they could remain in the facility,” read a statement by Médecins Sans Frontières on February 15.

Satellite imagery from Planet shows the progressive change in the hospital complex. Tents began appearing as early as mid-October and progressively grew until the IDF’s further advancement into Khan Yunis in January. A decrease in the number of tents is observed in mid-January, with most of them cleared in the beginning of February.

There appears to be no sign of people or trees in satellite imagery after the hospital was bombed; however, a March 9 broadcast by Al Jazeera shows a few rows of trees still standing. This can also be compared to footage from the ground uploaded by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019.

Al-Aqsa University campus in Khan Yunis (31.3560219, 34.2764004) was also used as a place of refuge. It was lush with trees and lawns which appear to have disappeared as encampments were built.

Satellite imagery captured on November 30 shows the presence of trees which gradually disappear in December. By early January, the campus and its adjacent areas were noticeably devoid of greenery and covered with temporary shelters. The tents were also visible on January 21, a day before the university was attacked.

In the latest satellite images, Al-Aqsa University campus appears destroyed and barren.

A Withering Landscape

Far from being merely examples of environmental destruction during conflict, the satellite images in this article tell the story of that damage from two angles. One is that of the Palestinian civilian victims who do not have the daily fuel or food required and and must create makeshift shelters on any land available.

The other angle is that of the IDF whose attacks against Gaza are targeting not just its civilian population, but also the landscape and vegetation that people need to survive.

Bellingcat contacted the IDF for comment and asked whether it considered the impact deforestation and destruction of agriculture was having on the civilian population. We had not received a response at time of publication.

Giancarlo Fiorella and Maxim Edwards contributed research. All timelapse videos created on Sentinel Hub.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh