On February 7th, 2024, a mystery vessel began leaking oil and ran aground on a reef 2024-2-14 23:48:3 Author: www.bellingcat.com(查看原文) 阅读量:23 收藏

On February 7th, 2024, a mystery vessel began leaking oil and ran aground on a reef off the coast of Tobago, one of the two main islands of the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago.

The resulting spill has coated beaches, wildlife, and over 80 kilometres of the Caribbean Sea, leading the government to proclaim a “national emergency”. Over a week later, the vessel remains unidentified by authorities.

Dive teams and an autonomous submersible have found a name for the vessel — the “Gulfstream” — but have been unable to locate an International Maritime Organization (IMO) registration number that would conclusively identify it.

Research by Bellingcat, including volunteers in our Discord community, suggests an explanation: the mystery vessel is an unpowered barge, part of a so-called articulated tug and barge system that did not have a registration number to begin with.

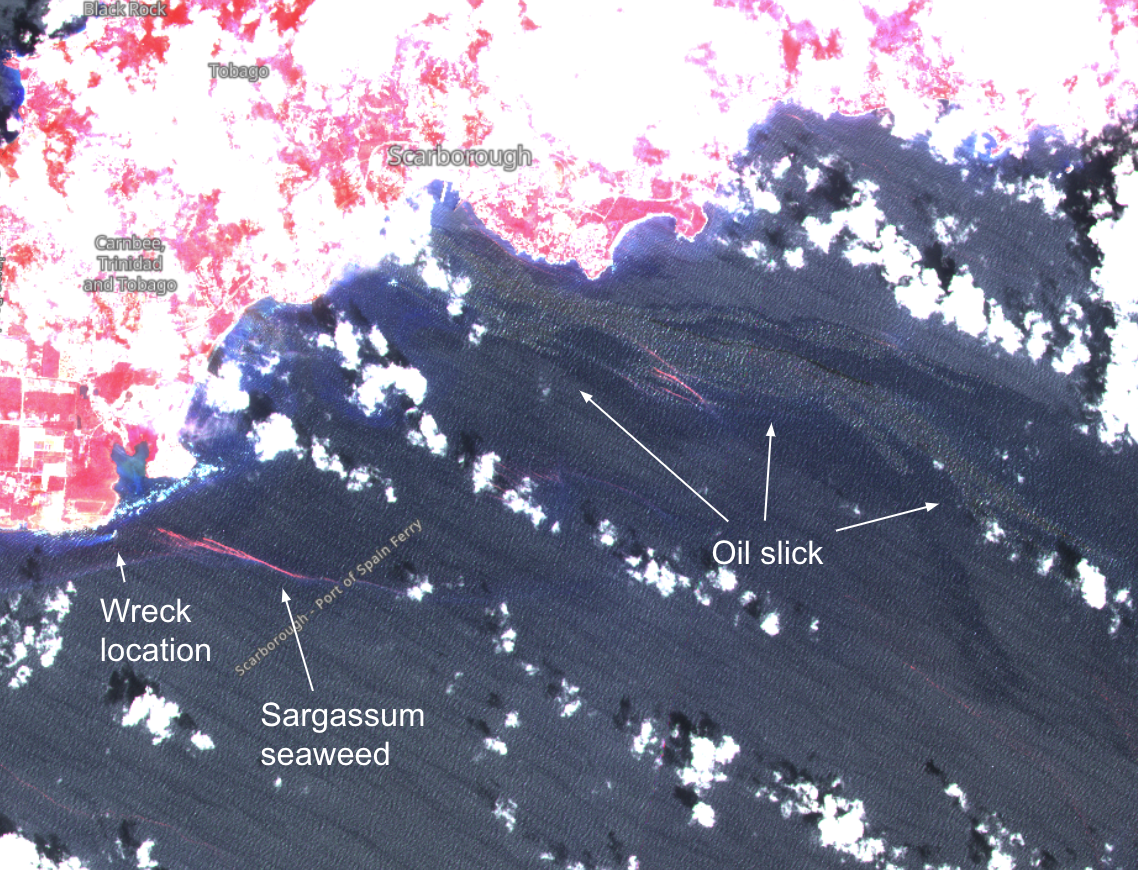

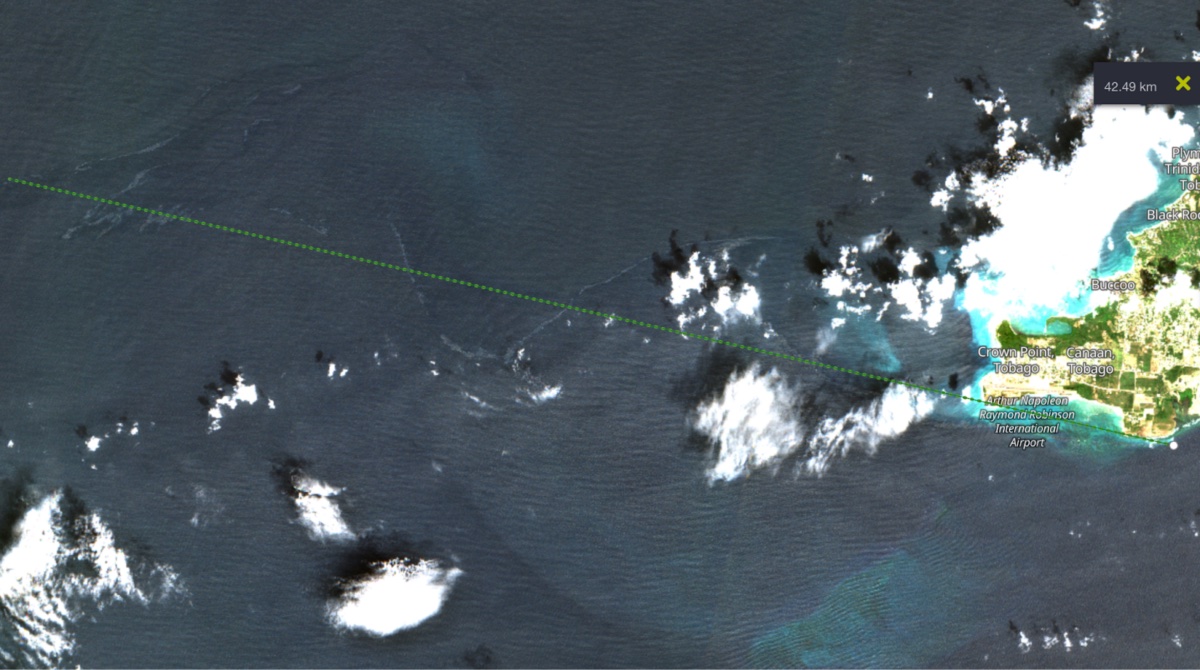

At 7:20am local time on the 7th, a wrecked vessel leaking oil was called into the Tobago Emergency Management Authority. Just a few hours later, an image taken by the Sentinel-2 satellite captured the vessel, as well as an oil slick over 10 kilometres long to the northeast that subsequently ran aground on the shallow coral reef directly off of Tobago.

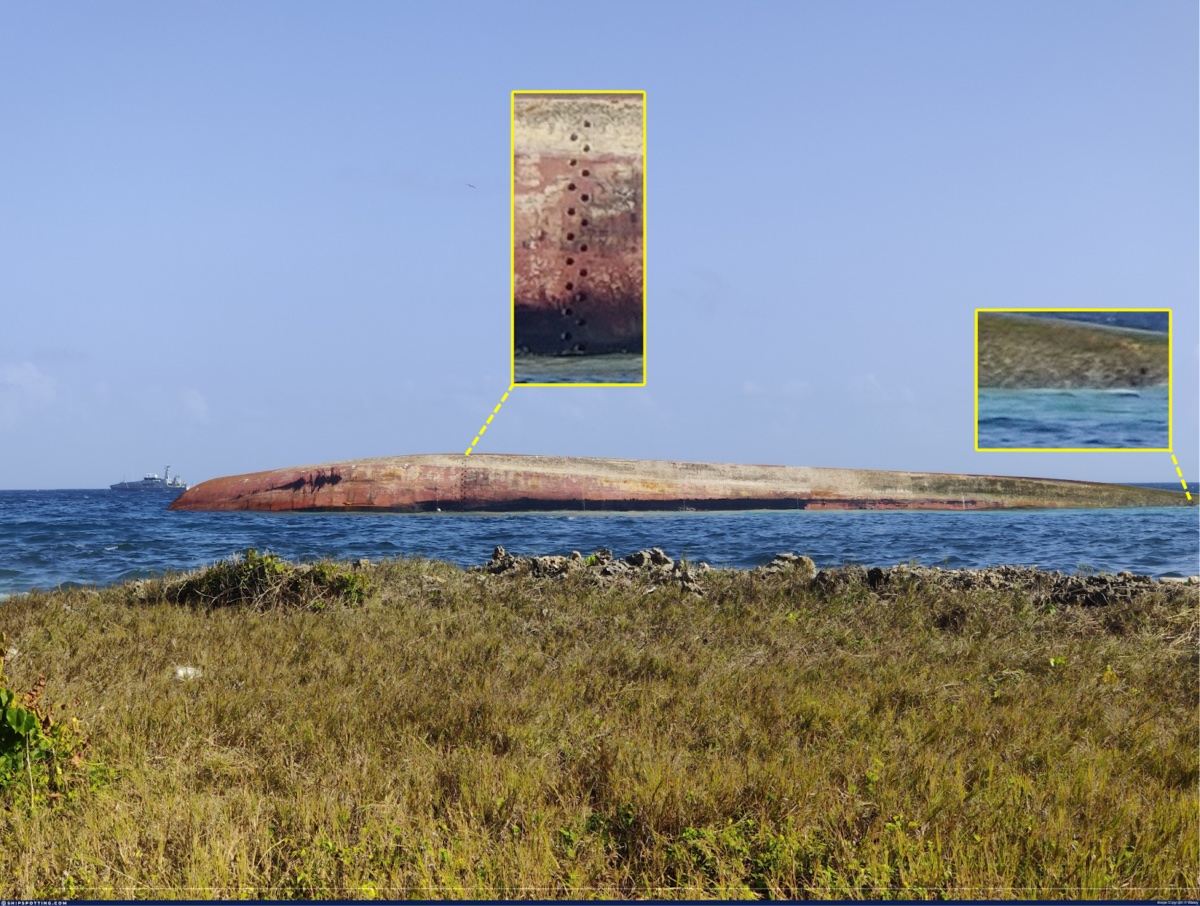

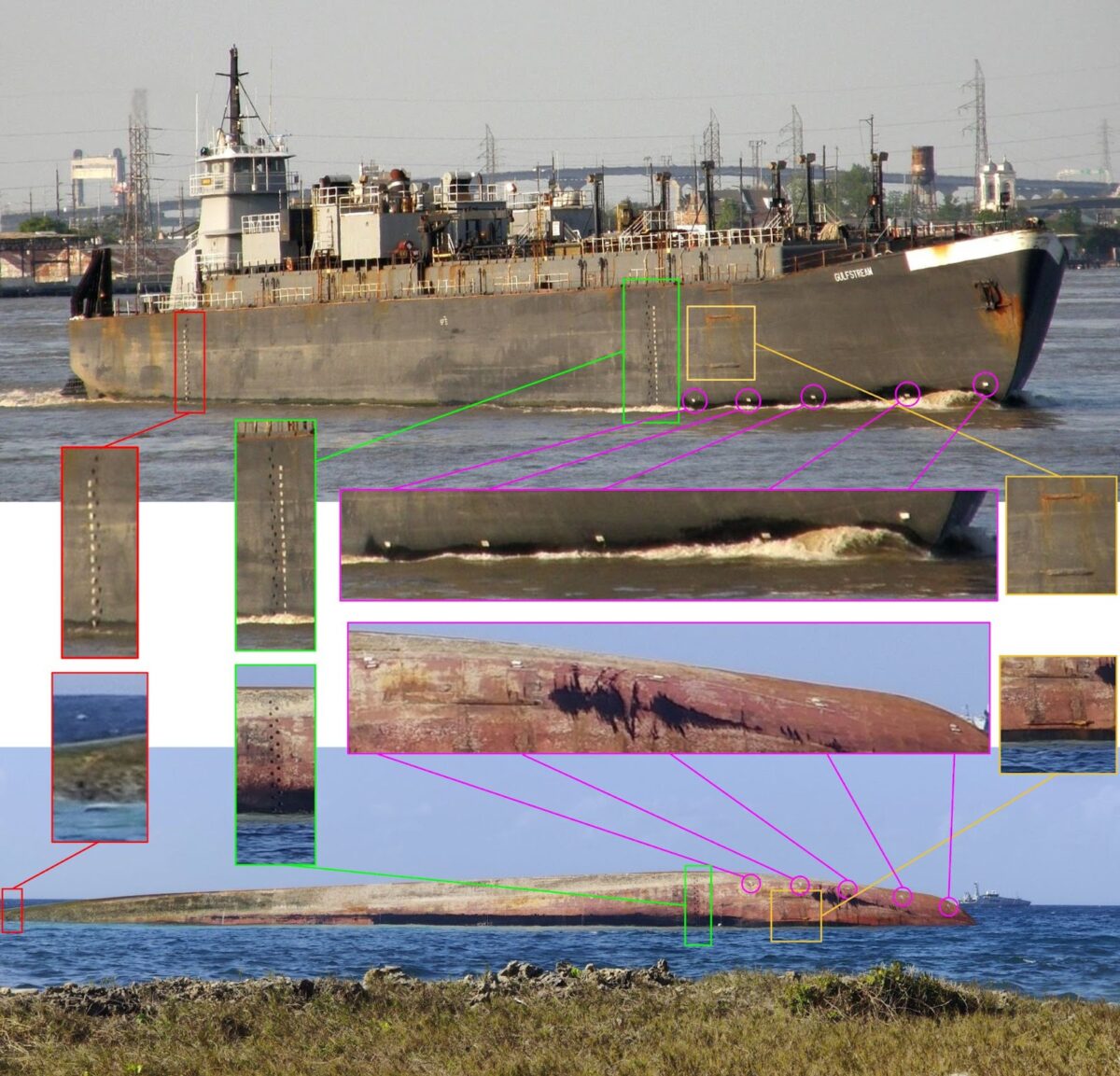

A photo posted by user “Wussy” on ShipSpotting.com reveals something interesting about the submerged vessel: the presence of “pigeonhole” ladders on the side of the hull. These are clearly visible near the left-hand side of the vessel and also barely visible on the right edge of the photo.

These pigeonholes are an unusual feature because they are typically not present on self-powered ships, but instead used on unpowered barges, which may be uncrewed and require exterior access from the water.

Because un-powered barges are regulated differently than self-powered vessels, open source information about them is spottier. However, Bellingcat did identify one barge named the Gulfstream, associated with a tug boat named Marlin, on the website TugboatInformation.com.

According to the site, “[The Marlin] was married to a 449(ft) 60,000 bbl double-hulled barge; the Gulfstream.” The tug and the barge operated as part of an “articulated tug and barge system,” or ATB. The tug is coupled to the rear of the barge in a special notch in the hull. This can be seen in this image by user Hans Rosenkranz from FleetMon.com.

Note also in this image, that while the Marlin tug has been painted with an IMO registration number, the barge itself only carries the name “Gulfstream” and text that reads “Philadelphia.”

Tugboatinformation.com also includes several other images of the vessel. Two were taken in 2009 and show the vessel operating heavily laden and low in the water.

A third image on Tugboat Information, undated and uncredited, shows the vessel’s bow with more of its hull exposed. Bellingcat identified the image as another photograph taken in 2008 by Rosenkranz, and obtained a higher resolution copy. In these images, it is possible to match the position of both sets of pigeonholes (red and green), as well as rubbing strakes (outlined in orange), to the capsized vessel in Tobago. The number of pigeonholes between the two visible strakes on the capsized vessel matches the number between the lower two strakes on the Gulfstream barge.

Additionally, a series of five sacrificial anodes (purple) can be seen along the bow of the Gulfstream. These would have been replaced many times between 2008 and 2024, but are still positioned in very similar locations.

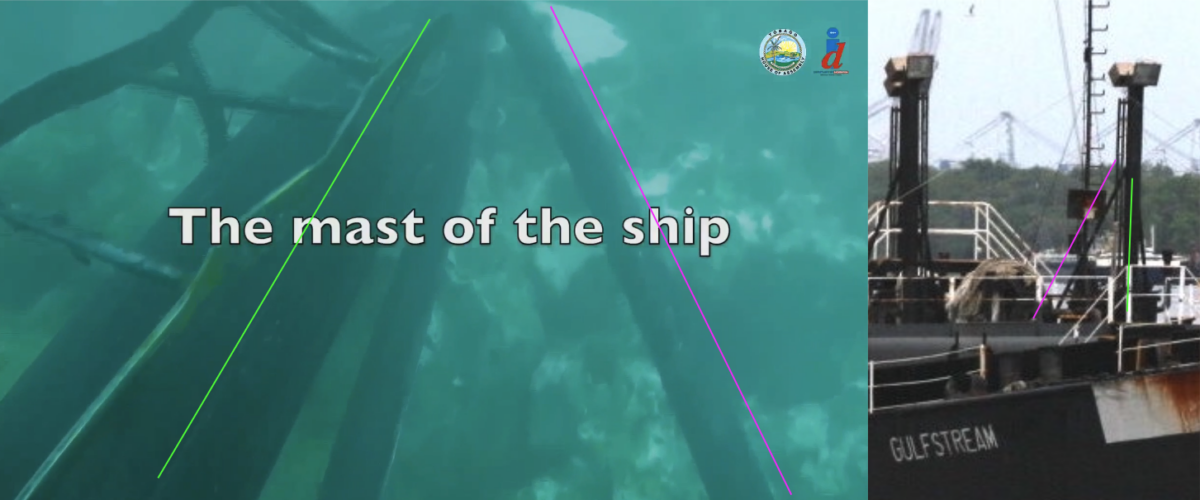

Additionally, clues are available from dive footage screened during a press conference by the Tobago House of Assembly, which shows a structure on the reef bottom (the footage begins 16:07 into the video). This structure, possibly misidentified as “the ship’s mast,” bears a resemblance to the lighting towers on the deck of the Gulfstream barge.

While photos from 2008 and 2009 show the Marlin/Gulfstream ATB system operating in the United States, records on vessel ownership tracking database Equasis show that the Marlin was sold in 2012 and purchased by San Martin Group Ltd, a Panamanian company. In 2014, AIS data shows that the vessel began regularly visiting petroleum ports in Venezuela and the Caribbean.

Equasis records only show the sale of the Marlin, because un-powered barges are not registered in the same way, as mentioned earlier. However, after the sale date, the vessels were also captured by imagery available on Google Earth, which clearly shows that the tug Marlin is still operating with its “married” barge Gulfstream, as in this image from a petroleum port in Maracaibo, Venezuela on March 8th, 2015.

Bellingcat followed the Marlin/Gulfstream using AIS data and satellite imagery until October 17th, 2020, when it transmitted its last AIS position at the ASTINAVE shipyard in Amuay, Venezuela. Satellite imagery shows that the barge remained at ASTINAVE for some time.

On February 18, 2021, ASTINAVE posted an image on Instagram showing the tug Marlin and the stern of the Gulfstream, with the caption “Posicionamiento de embarcacion en acople de trabajo,” or “Positioning of the vessel under coupling mode.”

On March 23, 2021, the owners of the Marlin/Gulfstream, San Martin Group Ltd, sold the vessels to another Panamanian company, Star Goods Petroleum S.A, which was registered in 2014.

For over a year, the vessel remained at the ASTINAVE shipyard, according to imagery from Planet Labs PBC and Google Earth. It was last seen in Planet imagery on February 22, 2022, where it is shown floating just offshore from the drydock. The vessel has not been visible at ASTINAVE after this date. It also has not transmitted an AIS message since.

There are few reasons why a vessel would not transmit AIS signals. One common reason is to obscure the origin and destination of the cargo it is transporting, though there is no conclusive evidence as to why signals from the Marlin/Gulfstream ceased.

Ships in so-called “ghost fleets” are sometimes used to transport sanctioned oil from Iran and Venezuela. In 2022, the Financial Times reported that the number of ships that have gone dark to operate in ghost fleets has tripled since 2019. Operating under the radar, these vessels are frequently poorly maintained — Reuters reported last year that more than half of Venezuela’s state-owned fleet of oil tankers are “so run down that they should be immediately repaired or taken out of service.”

The typical lifespan of a tanker is 30 years. As of 2014, the Marlin and the Gulfstream have been in service for 50 and 48 years, respectively.

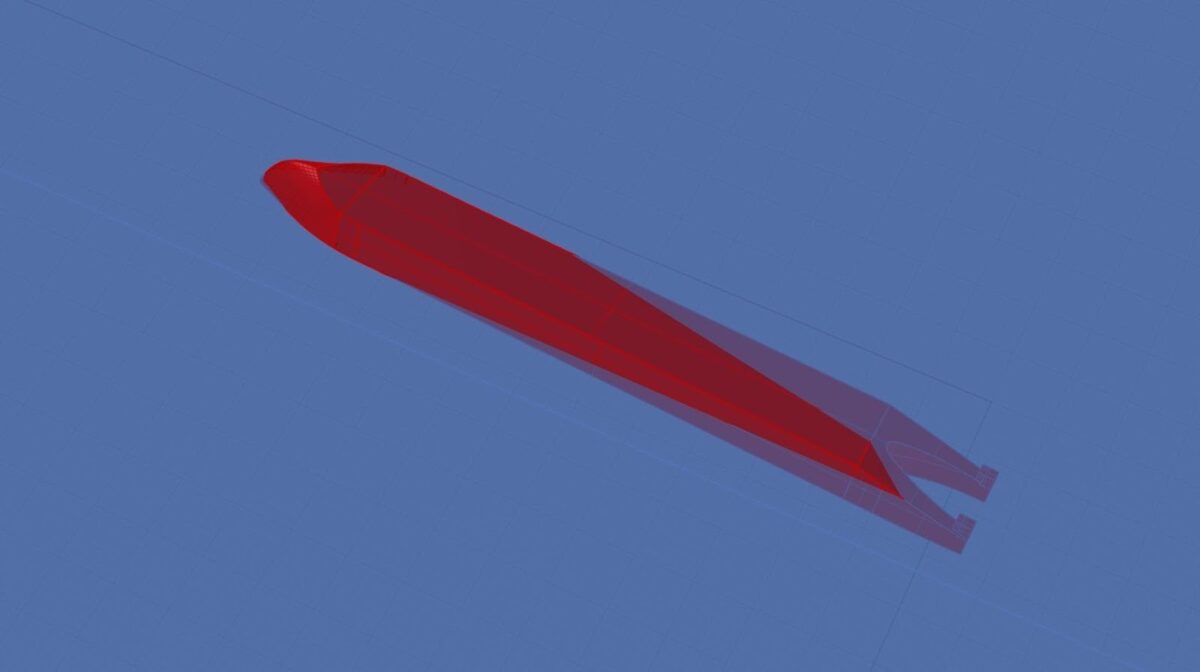

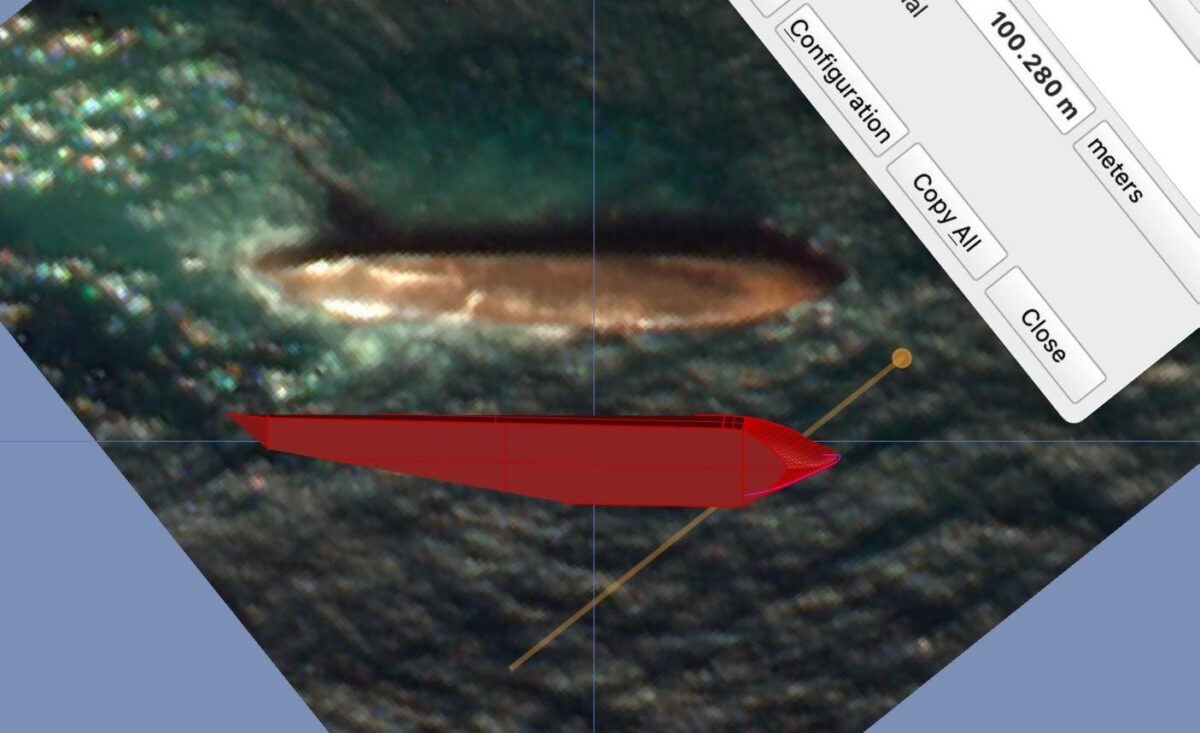

The Gulfstream barge has a unique shape, but it is not visible in images of the Tobago site. To evaluate the plausibility of the Gulfstream being the wrecked vessel, Bellingcat used ship-spotting photos and satellite imagery to build a to-scale 3D model of the Gulfstream barge. As the bottom of the vessel is not visible in available ship-spotting imagery, this model is approximate, using diagrams of other articulated-tug-and-barge systems available online.

Based on how the vessel sits on the reef, with its bow and starboard side sticking farther out of the water than the more deeply submerged stern, it seems plausible that this is the same vessel and that the tug-boat coupling is hidden beneath the water surface.

A to-scale comparison with high-res Planet SkySat imagery shows that the size and shape is an almost exact match.

Star Goods Petroleum S.A. does not have an online presence and its Panamanian registration documents contain no contact information. Bellingcat was able to locate the LinkedIn page of the company’s Executive Vice President. He did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

On Monday, February 12th, a Sentinel-2 image showed an oil slick snaking northwest from the crash site, in which it appeared to be still actively leaking. This oil extends for at least 40 kilometres into the Caribbean Sea, showing the ongoing extent of the spill.

In a Tuesday X post, one Tobagonian shared aerial imagery of a beach in Scarborough, Tobago. Covered in thick black oil a few days previously, clean-up work by local volunteers had removed much of the visible oil, the beginning of an arduous remediation process from this environmental disaster.

Additional research by members of Bellingcat’s Discord community, including Lotte van der Waal, Thomas Bordeaux and Ethan Doyle. 3D modelling by Alison Malouf.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Instagram here, X here and Mastodon here.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh