Executive SummaryGlupteba is 2024-2-12 22:0:28 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:59 收藏

Executive Summary

Glupteba is advanced, modular and multipurpose malware that, for over a decade, has mostly been seen in financially driven cybercrime operations. This article describes the infection chain of a new campaign that took place around November 2023.

Despite being active for over a decade, certain capabilities that Glupteba’s authors have added have remained undiscovered or unreported – until now. We will focus on one intriguing and previously undocumented feature: a Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) bootkit. This bootkit can intervene and control the OS boot process, enabling Glupteba to hide itself and create a stealthy persistence that can be extremely difficult to detect and remove.

While this threat began as a simple backdoor, it transformed into a potent botnet, emerging as a major player in the realm of cyberthreats. Since its discovery in the early 2010s, Glupteba has evolved significantly and undergone a series of stealthy metamorphoses. This threat is particularly known for its elaborate infection chains that showcase its operators’ continuous developments and their attempts to evade traditional security measures.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from malware discussed in this article through products like Cortex XDR, our Next-Generation Firewall with Cloud-Delivered Security Services that include Advanced WildFire, Advanced Threat Prevention and Advanced URL Filtering. Additionally, Prisma Cloud Cortex XDR Cloud Agents or Prisma Cloud Defender Agents monitor for instances of known Glupteba malware. DNS Security can block malicious domains.

Specifically for UEFI bootkits such as Glupteba’s, the UEFI Protection module released as part of Cortex Agent 8.3 provides detection and prevention capabilities.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Malware, Botnet |

A note on acronyms: this article uses multiple acronyms. We’ve listed out terms that are either used together in sequence or may be unfamiliar to analysts of different backgrounds.

| Acronym | Term |

| DSE | Driver signature enforcement |

| ESP | EFI system partition |

| PPI | Pay-per-install |

| SPI | Serial Peripheral Interface |

| UEFI | Unified Extensible Firmware Interface |

| UPGDSED | Universal PatchGuard and Driver Signature Enforcement Disable |

Table of Contents

Glupteba Overview

About Glupteba’s PPI Ecosystem

2023 Campaign

Exploring Glupteba's Undocumented UEFI Bootkit

UEFI Bootkit Introduction

Uncovering Glupteba’s Bootkit Installer

EfiGuard

EfiGuard in Glupteba

Summary of DSE Bypasses in Glupteba

Conclusion

Protections and Mitigations

Indicators of Compromise

Glupteba Binaries From the 2023 Campaign

2023 Campaign ZIP Files

EfiGuard Binaries Used by Glupteba

2023 Campaign Infrastructure

Location of Program Database (PDB) File From Glupteba in 2023

Additional Resources

Glupteba Overview

Glupteba is built to be modular, which allows it to download and execute additional components or payloads. This modular design makes Glupteba adaptable to different attack scenarios and environments, and it also allows its operators to adapt to different security solutions.

Over the years, malware authors have introduced new modules, allowing the threat to perform a variety of tasks including the following:

- Delivering additional payloads

- Stealing credentials from various software

- Stealing sensitive information, including credit card data

- Enrolling the infected system in a cryptomining botnet

- Crypto hijacking and delivering miners

- Performing digital advertising fraud

- Stealing Google account information

- Bypassing UAC and having both rootkit and bootkit components

- Exploiting routers to gain credentials and remote administrative access

In recent campaigns, threat actors mainly distributed Glupteba through pay-per-install (PPI) services, which allowed the operators of this malware to mass-infect machines all over the world.

About Glupteba’s PPI Ecosystem

The PPI ecosystem is a significant and profitable component of the cybercrime landscape. This model, which initially emerged as a means to distribute advertisements, evolved over the years toward a more nefarious purpose: the dissemination of spyware and malware.

This model facilitates widespread distribution of malicious software, as financially incentivized PPI service providers play a crucial role in disseminating malware. This includes threats ranging from advanced downloaders like PrivateLoader and SmokeLoader to versatile threats like Glupteba, RedLine Stealer, coin miners and even ransomware.

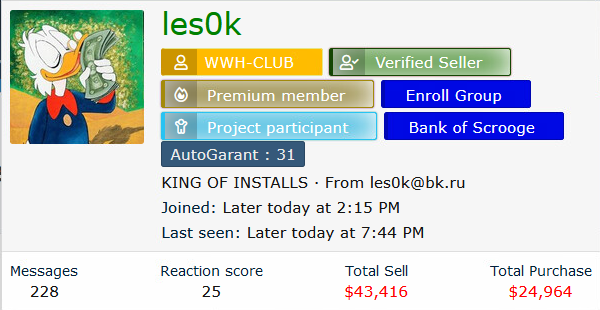

PPI service providers use different platforms to recruit affiliates and sell services. One of the most popular PPI services that spreads PrivateLoader is called Ruzki. Ruzki is operated by the user les0k on Russian hacking forums. Figure 2 shows an account overview of les0k on the Russian hacking forum WWH, also known as WWHClub.

To attract malware operators, PPI services sometimes post promotions and offer discounts. Pricing is based on the number of installations requested, and in most cases pricing is also based on region.

Figure 3 shows an example where a PPI service provider is requesting $70 USD for 1,000 installations worldwide, excluding Europe and the U.S. One thousand installations in Europe costs $500, and the same number of installations in the U.S. will cost the operator $1,200.

2023 Campaign

Since December 2022, Glupteba has sprung back into action, infecting devices worldwide after its operation was disrupted by Google in December 2021. The activity continued into 2023, when the Glupteba botnet reemerged in a new, ongoing and widespread campaign affecting multiple regions and industries. Organizations hit by this campaign were based in countries including Greece, Nepal, Bangladesh, Brazil, Korea, Algeria, Ukraine, Slovakia, Turkey, Italy and Sweden.

Similar to other recent campaigns, threat actors often spread Glupteba through web-based distribution and large-scale phishing attacks using bundled software installation files and cracks, as shown in Figure 4. This strategy has led to multiple malware infections.

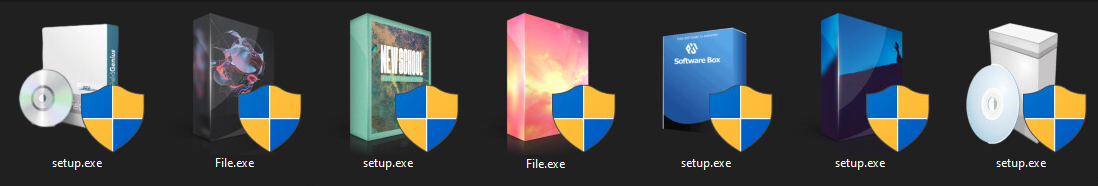

The campaign has multiple stages, as shown in Figure 5. The first stage of an attack lures a user into downloading malicious ZIP files of fake installation files impersonating different software. Once the user downloads the ZIP file and attempts to install the software, the infection chain begins.

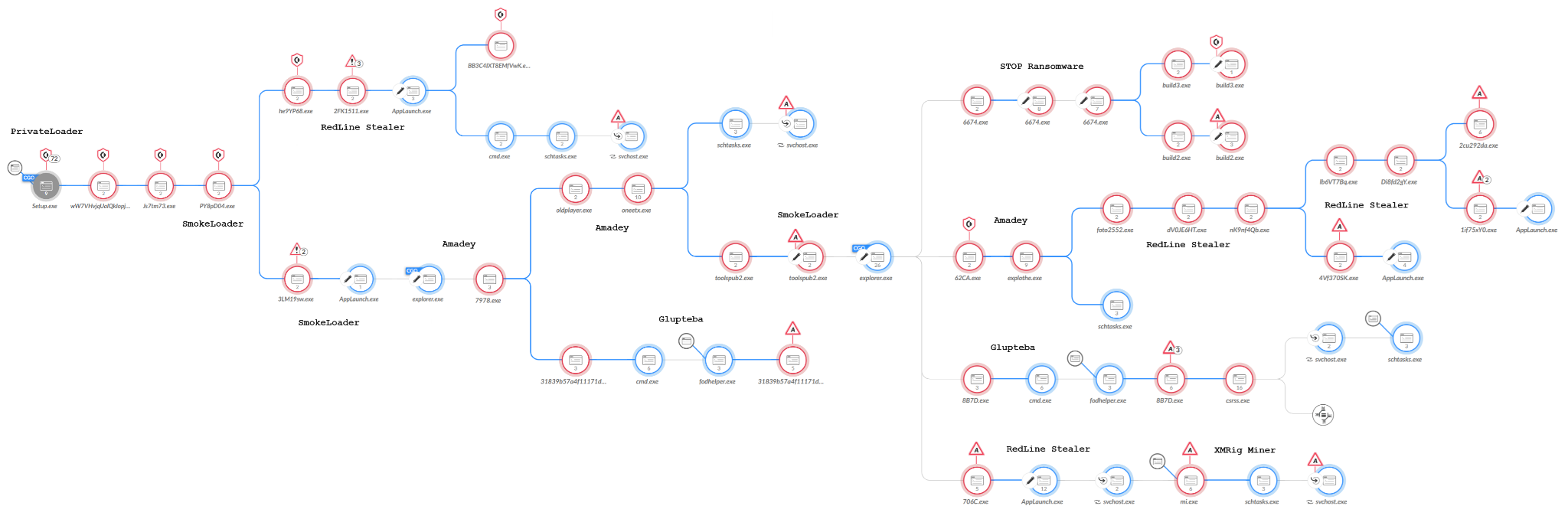

Threat actors often distribute Glupteba as part of a complex infection chain spreading several malware families at the same time. This infection chain often starts with a PrivateLoader or SmokeLoader infection that loads other malware families, then loads Glupteba.

For example, Figure 5 above shows a 2023 infection chain that starts with PrivateLoader, which led to SmokeLoader, which then led to a variety of other malware including two Glupteba samples.

The infection chain shown in Figure 5 is one of many similar chains we discovered in 2023. Our analysis of these recent campaigns revealed Glupteba’s use of an undocumented UEFI bootkit.

Exploring Glupteba's Undocumented UEFI Bootkit

Before discussing Glupteba’s implementation of the UEFI bootkit, first is a short introduction to UEFI bootkits and their complexity.

UEFI Bootkit Introduction

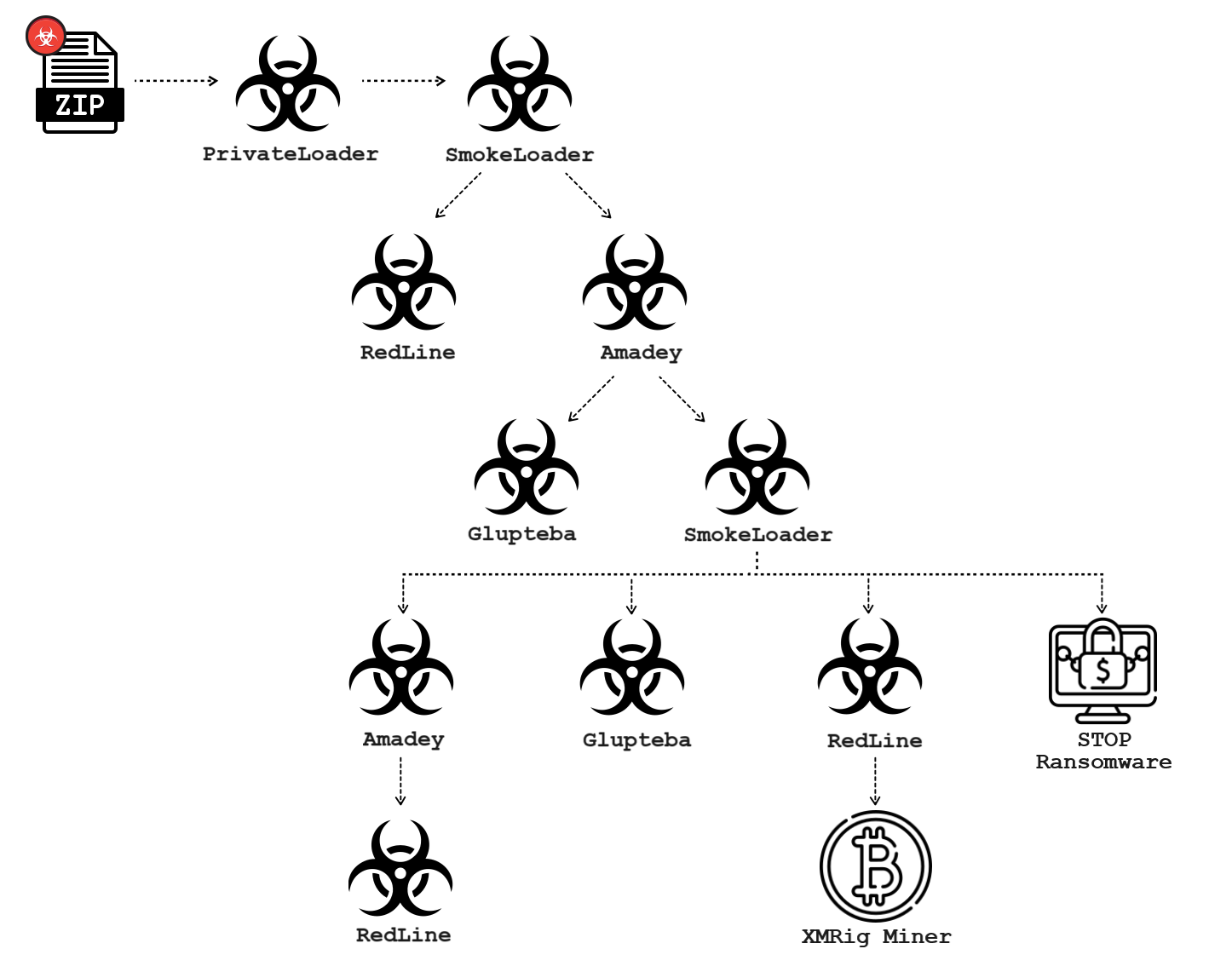

UEFI is a specification that defines the architecture of the platform firmware used for booting the computer hardware and its interface for interaction with the operating system.

Figure 6 reveals the different stages of the boot process in a UEFI system.

In the stages before boot device selection in Figure 6, the system’s firmware is loaded from a Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) flash memory. Then the EFI system partition (ESP), located in the boot device and containing the Windows Boot Manager, is loaded as the host boots into Windows.

A malware implant in the ESP is enough to execute code before Windows starts, where it can easily disrupt various security mechanisms. Another possibility is an implant in the SPI flash memory that executes code at earlier stages of the boot process, enabling even greater power and flexibility. However, malware using a firmware implant in flash memory requires higher privileges than using an ESP implant. This is more complex.

As of 2023, only a handful of UEFI bootkits have been publicly reported in the wild, such as LoJax (a firmware implant) and BlackLotus (an ESP implant).

Uncovering Glupteba’s Bootkit Installer

We start our analysis with a bootkit installer binary disguised as a legitimate Windows binary (csrss.exe). When analyzing this installer, a clear lack of strings and functions indicates the file is packed in some way. This means we have some work to do before we can analyze the actual logic of the installer.

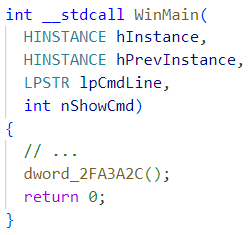

After examining the installer with a dissembler, the main function appears to eventually jump into an address stored in dword_2FA3A2C as shown below in Figure 7.

Another function, dword_2FA3A2C, is assigned newly allocated heap memory and then set with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE permissions (see Figure 8). Finally, this heap memory is filled with some data, which is at least partially executable.

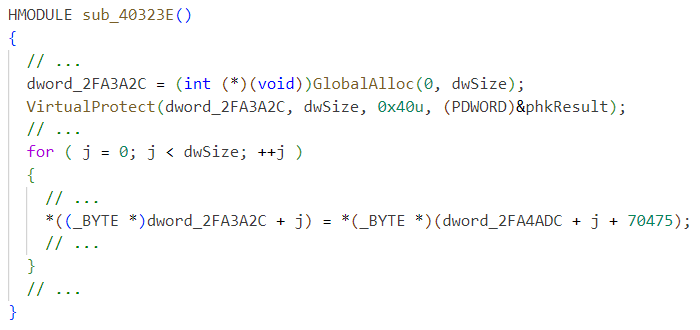

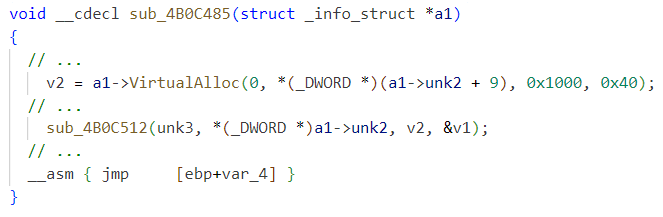

Further unpacking takes place after jumping to this code, eventually allocating another RWX memory and jumping to it, as shown in Figure 9.

This memory area contains unpacked resources, including the PE file with the main installer logic. All other resources that are not related to the UEFI bootkit are out of scope here.

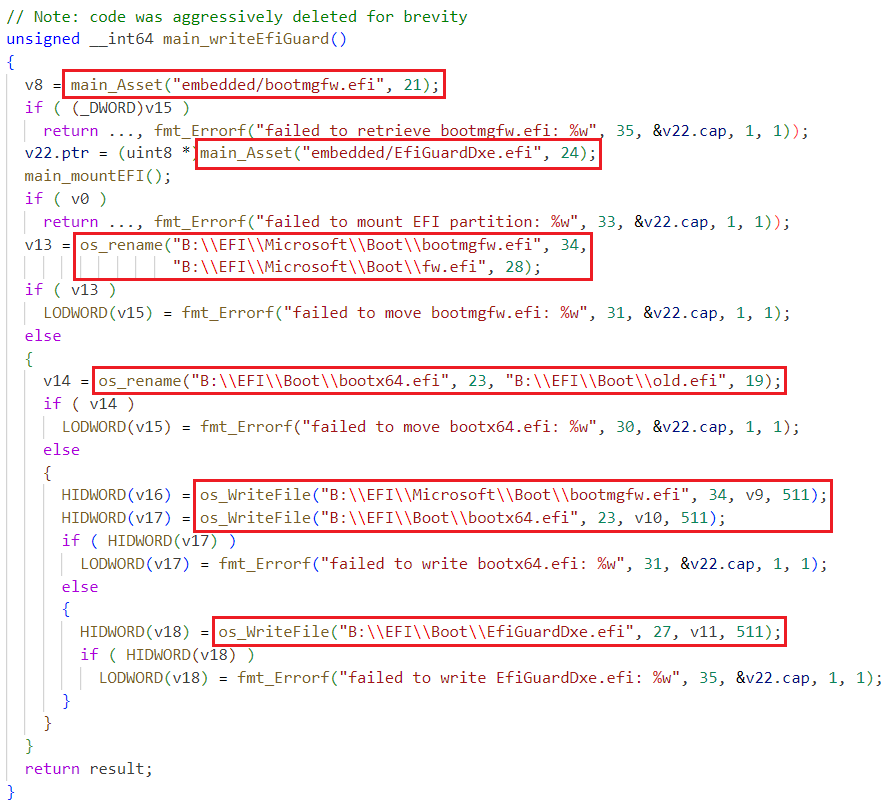

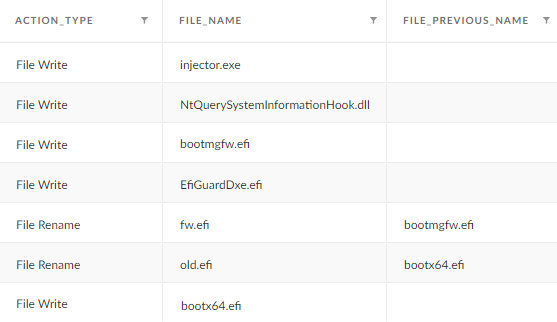

The installer has a function main_writeEfiGuard that writes files in the ESP as seen in Figure 10.

Summary of the operation of this function:

- The main_mountEFI function mounts the ESP into the B: drive

- B:\EFI\Microsoft\Boot\bootmgfw.efi is renamed to B:\EFI\Microsoft\Boot\fw.efi

- B:\EFI\Boot\bootx64.efi is renamed to B:\EFI\Boot\old.efi

- The asset embedded\bootmgfw.efi is written to B:\EFI\Microsoft\Boot\bootmgfw.efi and to B:\EFI\Boot\bootx64.efi

- The asset embedded \EfiGuardDxe.efi is written to B:\EFI\Boot\EfiGuardDxe.efi

These actions can be viewed as Cortex XDR events – see Figure 11.

The name of the function (main_writeEfiGuard) and the name of one of the dropped files (EfiGuardDxe.efi) immediately point us in the direction of EfiGuard.

EfiGuard

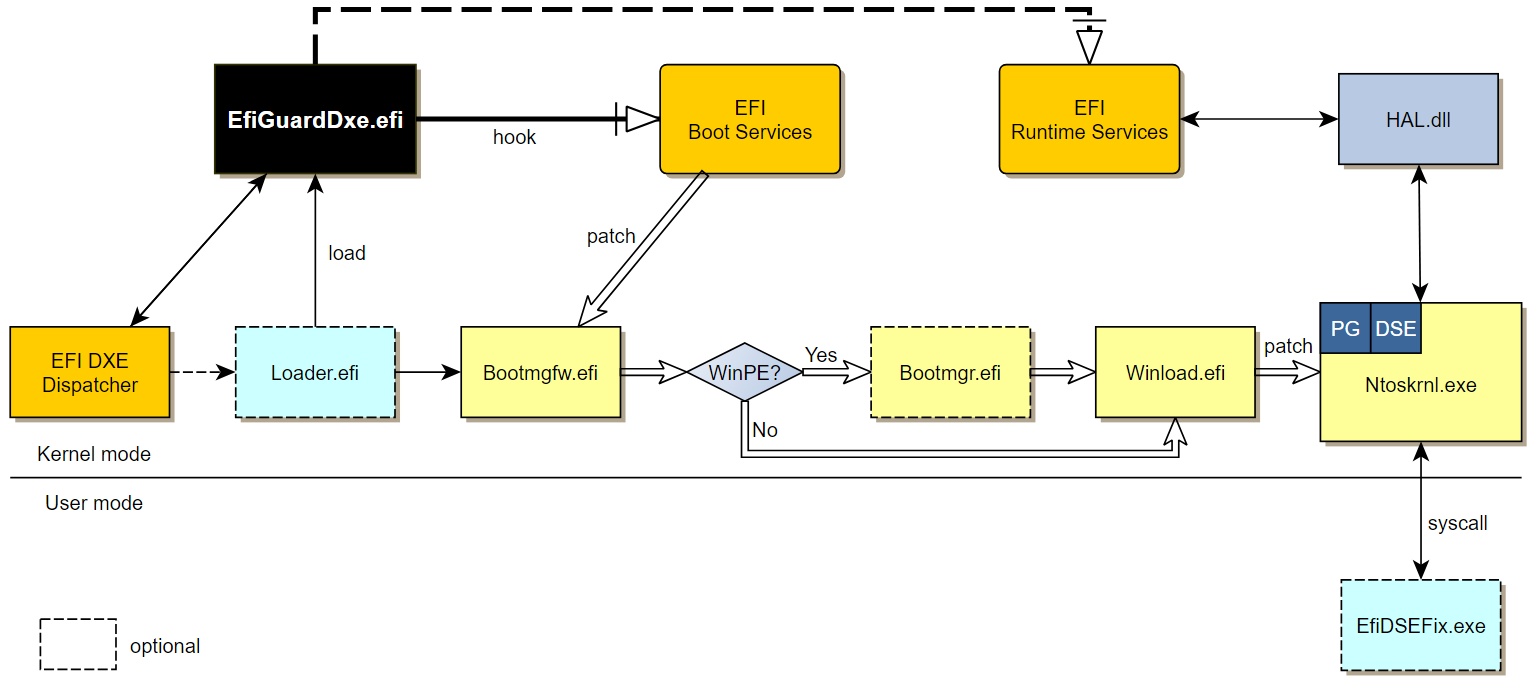

EfiGuard is an open-source and portable UEFI bootkit that patches the Windows kernel by executing a UEFI driver (EfiGuardDxe.efi) to disable PatchGuard and driver signature enforcement (DSE). Figure 12 depicts the architecture of EfiGuard.

As documented in the GitHub project, EfiGuardDxe.efi can be executed either by installing it in a UEFI driver entry or booting a custom loader (Loader.efi) that loads the driver and then continues to load Windows. Glupteba uses the latter method.

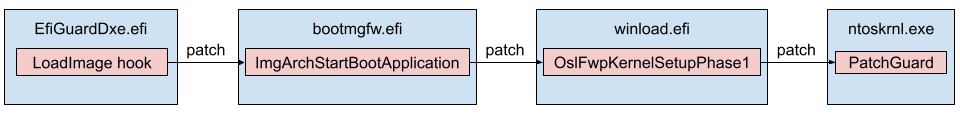

In either case, the driver hooks the EFI Boot Service LoadImage function, which intercepts the loading of the Windows Boot Manager (bootmgfw.efi), starting a chain of patches that eventually patch the kernel (ntoskrnl.exe) as depicted in Figure 13.

The project supports two methods for disabling DSE. The first occurs at boot time, immediately after disabling PatchGuard. The second involves leaving a UEFI backdoor through a hook on the EFI Runtime Service SetVariable that allows user-mode code to read and write arbitrary kernel-space memory. The backdoor is complemented with a user-mode program (EfiDSEFix.exe) that utilizes the kernel read/write backdoor to patch DSE.

EfiGuard in Glupteba

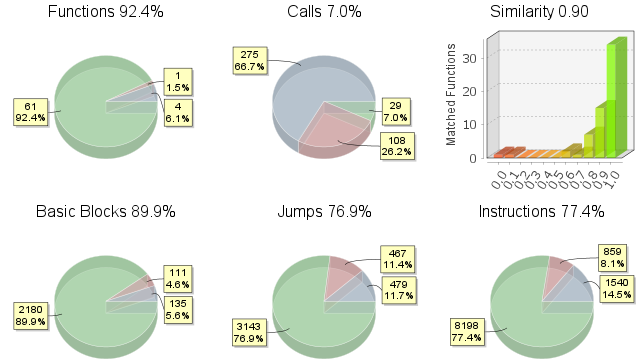

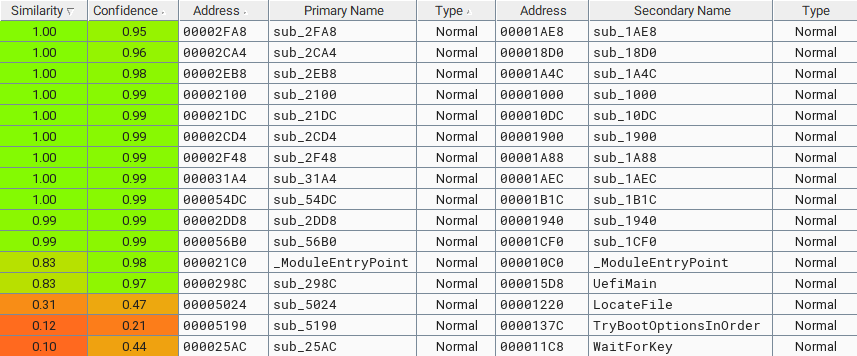

Using Bindiff for a similarity analysis of the two files Glupteba writes in the ESP quickly indicates they are a recompilation of the EfiGuardDxe.efi and Loader.efi components in EfiGuard, as shown below in Figures 14 and 15. Some code, such as logs, was removed from EfiGuard.

Glupteba replaces the Windows Boot Manager (bootmgfw.efi) with Loader.efi. The Loader.efi file loads the EfiGuardDxe.efi driver and then continues to load Windows.

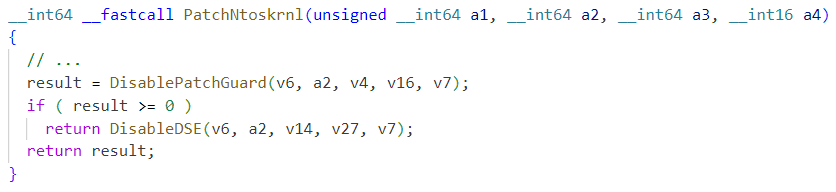

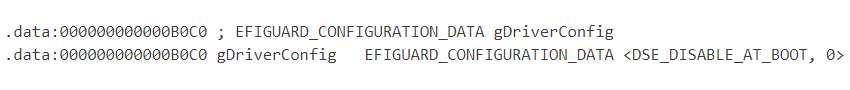

It appears the threat author has manually modified and recompiled the driver code to use the boot time method to disable PatchGuard and DSE, as shown in Figure 16 below. Note that the driver configuration for the bypass method, stored in gDriverConfig, is set to DSE_DISABLE_AT_BOOT – see Figure 17. However, the author actually removed the code paths that check this configuration in our sample.

Summary of DSE Bypasses in Glupteba

As documented in a previous analysis by Sophos, Glupteba formerly used Windows kernel drivers to hide itself. To successfully load these drivers, Glupteba used DSEFix or Universal PatchGuard and Driver Signature Enforcement Disable (UPGDSED).

DSEFix drops a known vulnerable driver and exploits it to disable DSE in kernel memory. UPGDSED runs in user-mode and patches the Windows kernel and Windows Boot Loader binaries for the same purpose.

Our current samples reveal that Glupteba has added EfiGuard to its arsenal of tools that are capable of disabling DSE.

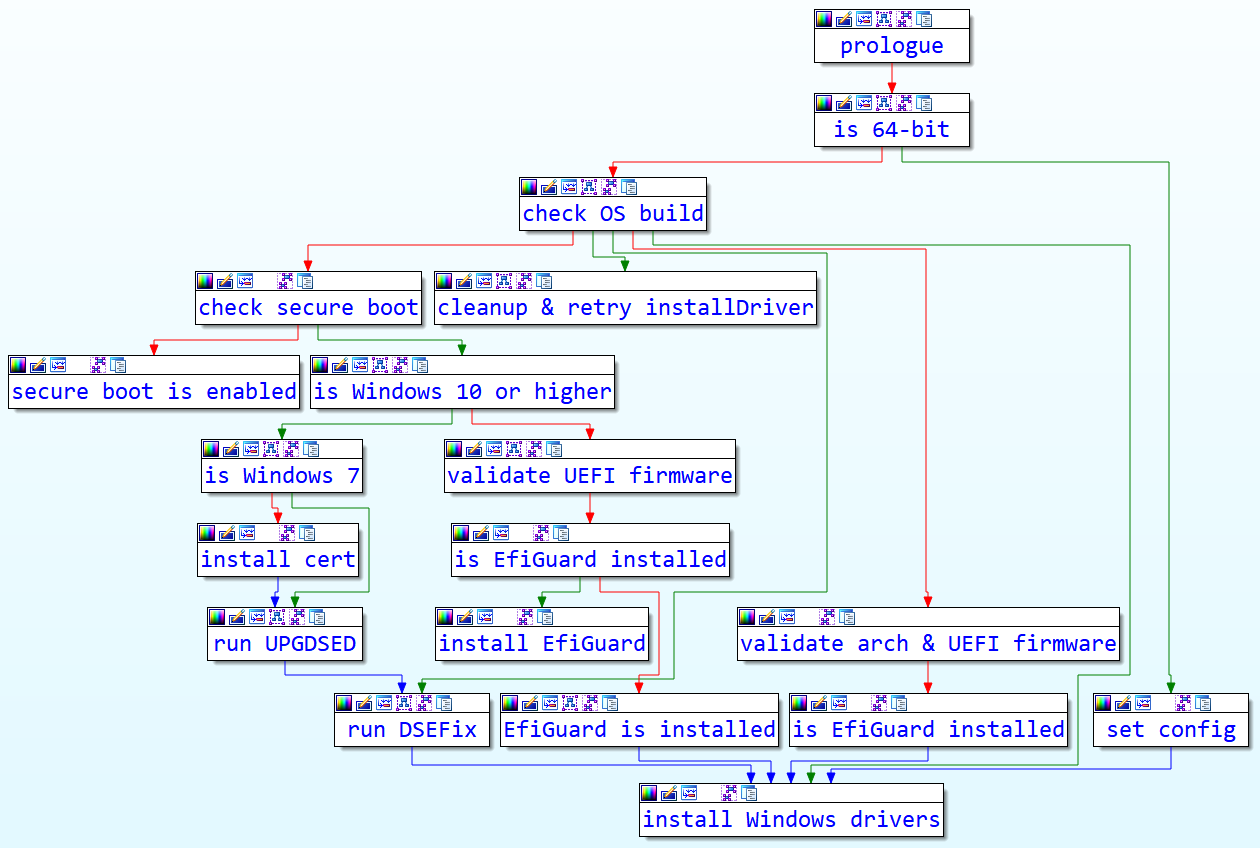

In the installer, the function main_installDriver calls the previous function we analyzed (main_writeEfiGuard), which writes the files in the ESP. We give a high-level overview of the logic in this function in Figure 18 below, by grouping its nodes in IDA.

As revealed in Figure 18, any one of the three DSE bypasses we have mentioned (DSEFix, UPGDSED or EfiGuard) might be used, depending on the architecture, OS version and configuration. Unlike the BlackLotus ESP implant, we have not seen any evidence for Glupteba bypassing Secure Boot.

Conclusion

In the ever-evolving threat landscape, Glupteba malware continues to stand out as a notable example of the complexity and adaptability exhibited by modern cybercriminals.

The identification of an undocumented UEFI bypass technique within Glupteba underscores this malware's capacity for innovation and evasion. This novel method not only poses a significant challenge for detection but also highlights the pressing need for cybersecurity professionals to continually enhance their defenses and stay ahead of emerging threats.

Furthermore, with its role in distributing Glupteba, the PPI ecosystem highlights the collaboration and monetization strategies employed by cybercriminals in their attempts at mass infections. This model indicates that threat actors leverage underground economies to proliferate malware, and it emphasizes the importance of holistic cybersecurity strategies and multilayer security solutions that extend beyond traditional defenses.

Protections and Mitigations

Cortex XDR and XSIAM raised many alerts for the malicious activities observed in the 2023 campaign distributing Glupteba and other malware. Prevention and detection alerts revealed the different stages and different malware involved.

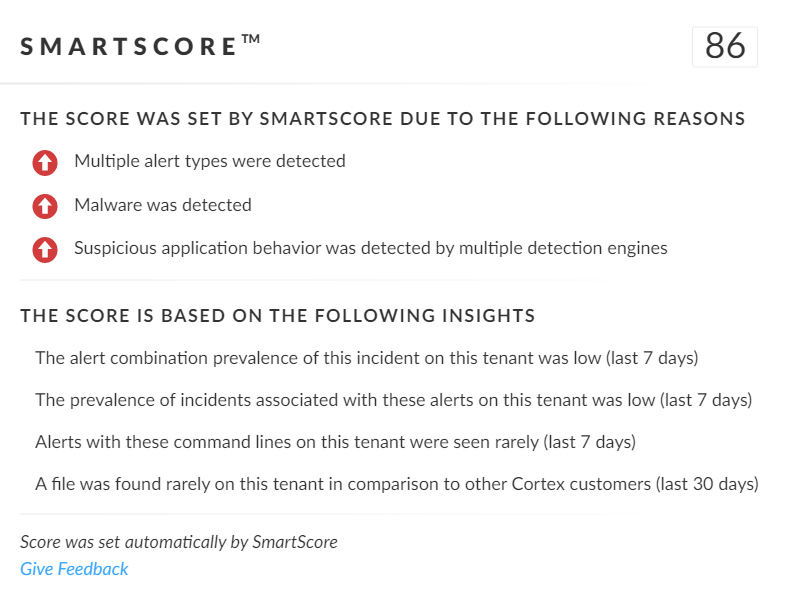

SmartScore, our unique ML-driven scoring engine that translates security investigation methods and their associated data into a hybrid scoring system, scored this incident an 86 out of 100, as shown below in Figure 19. This type of scoring helps analysts determine which incidents are more urgent and provides context about the reason for the assessment, assisting with prioritization.

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with this group:

- The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of the IoCs shared in this research.

- Next-Generation Firewall with Cloud-Delivered Security Services including Advanced URL Filtering, Advanced Threat Prevention and DNS Security identify domains associated with this group as malicious.

- Prisma Cloud: Any cloud infrastructure running Windows virtual machines should monitor their Windows-based VMs using Cortex XDR Cloud Agents or Prisma Cloud Defender Agents. Both agents will monitor the Windows VM instances for known Glupteba malware, using signatures pulled from Palo Alto Networks Wildfire.

- Cortex XDR

- Prevents the execution of known malicious malware, and also prevents the execution of unknown malware using Behavioral Threat Protection and machine learning based on the Local Analysis module.

- Protects against credential gathering tools and techniques using the new Credential Gathering Protection available from Cortex XDR 3.4.

- Protects from threat actors dropping and executing commands from web shells using Anti-Webshell Protection, newly released in Cortex XDR 3.4.

- Protects against exploitation of different vulnerabilities including ProxyShell and ProxyLogon using the Anti-Exploitation modules as well as Behavioral Threat Protection.

- Cortex XDR Pro detects post-exploit activity, including credential-based attacks, with behavioral analytics.

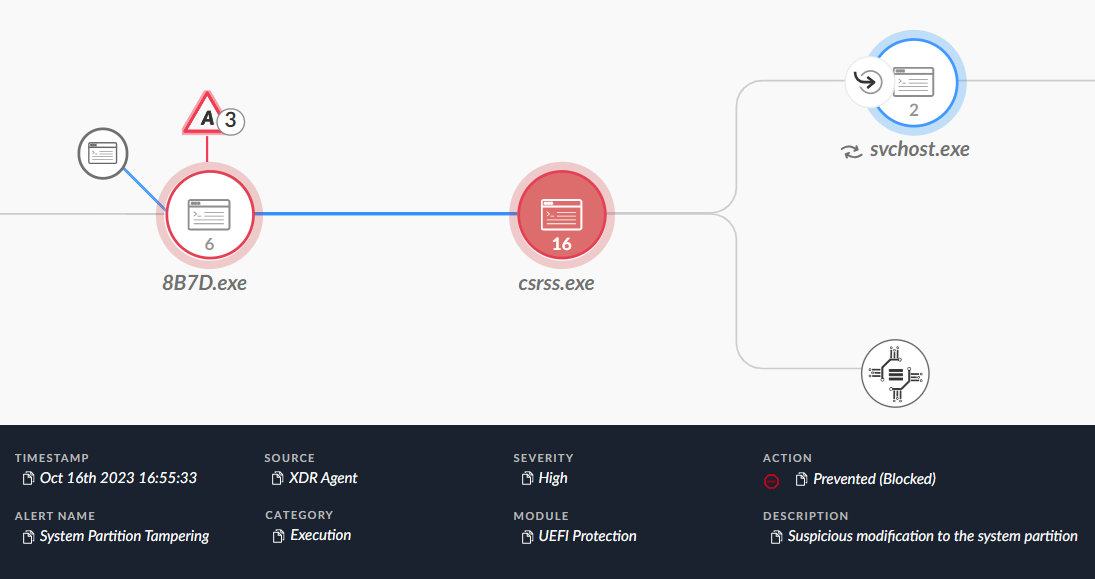

- The UEFI Protection module detects and prevents advanced threats that target UEFI. In the case of Glupteba, Figure 20 shows the module blocking the malicious modifications made to the ESP.

If you think you might have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Glupteba Binaries From the 2023 Campaign

- cfc7111da7b09e7a93b93ce690f2a4d922cc1009fea8368300f06c6fa4f85472

- 17e4590eceb4fec1e08c29b206d424172753d8472395f37d0647249ceff25817

- 61ab0e1ddaae4704999c4781deea56e1df5b05489bf4c0b892c47b36a63de9f4

- b6604ae49298c59e148b1e741ef8821ffd60c775bfb9c3234783452c54cd3069

- 8e380777da39ad7a588f4d9b703adc18b4ba935c21b17f215a3da5792672f205

- e4a2b53965b9d203d13dd4b5962b9f07270bb87e5738f44cf1126ce36019427d

- c353fb081ae8e121c4dcea3ad1bc4061315728a6f0d0ac63885a4f074be5fef3

- df75b62e373e0b91f26384b21aaa8e4dc86c13078cec7e32ad595d0c86d3fedb

- 5851e0b4a79208b995ab5a7e1f5247c159aac31c7c166a4bef77be14af64c1e8

- 6263a6ceb172eed7bae158d8066f70cabc42b352129547e1b5ad0c1096319d30

- 9c44bf6c3538c93c95342f5c365de46b6494a5a5764870048df7478a9d0f8723

- b84adf0716facf50418f5f228cf095e5157b6be3f04a98f26ce833057e804a4f

- a000684c9fcd2d5a528161a3513f726b2307fa6b50788a568fec0930b452d59e

- c867c3bda7b6f6bd228a4d7656c069bd6cf4f67ba4b075cf4113f5b109e7d9ee

- 8a62d01c1f321c4adb8428771af3eae1c83fec8a0e0a047b0bc17a51d19c7c96

2023 Campaign ZIP Files

- cb347e06d97fde4c7f8dd77be59b8f57d47f6e3f998d708d21a5963bc1620835

- 46eb8b98738df13a3a8c923228ca82006c7d403c7a1aac2d6bc752023b432915

- aa3257efb3182a98f73ad413b34f68067f42c3c51b68d15abea5db01173afad8

- 75bb73decf9fd21643b834a0b3e21e8e0d33910e51efbe56a2162f1180d04802

- 18c6e5a916eea979ea52495309e4e643232832bea614688df4cec0e3123b09d0

- fdd2fbe16f96f6d2b027347fd35c2e105a483a55b43f094754c2b3374ffb051a

- 9691b5846e230e0ea87b3f8a7a6dc31daae701ca0bb83e6c7df0f683bdea01e6

- 9c6af24c519d02203bfbdf568f7beb144996af9676b290a96a728ba9314b1c66

- bb809863b3145ceef7fc12ae5bca3940f18c4a24f5b4652e7b4cea6847762887

- 3a1cffaaa68dc4b5f0f94a1ec14b008444074a3faefa4beba20c857a21539bc1

- d0d58229650ff9bf3bbf8edb55c7058a2f243e900473e0ff8849c517c2f165bd

- c4f45bdfecb3d8cb4dcfdc8f323cf5d15321d161ac92802aa1e77dfa94fd91ed

- 84575070117b8896bafbd6f5dc364db09bea8e742f4af84884d15cab5e811060

EfiGuard Binaries Used by Glupteba

- 9fdb7c1359f3f2f7279f1df4bde648c080231ed21a22906e908ef3f91f0d00ee

- 01e86a4dfe6e0de7857b3cf2fafd041c8b3a3241e00844cb6bfbd3bfae2d36bc

2023 Campaign Infrastructure

- weareelight[.]com

- onualituyrs[.]org

- snukerukeutit[.]org

- stualialuyastrelia[.]net

- sumagulituyo[.]org

- criogetikfenbut[.]org

- dpav[.]cc

- humydrole[.]com

- kggcp[.]com

- kumbuyartyty[.]net

- lightseinsteniki[.]org

- liuliuoumumy[.]org

Location of Program Database (PDB) File From Glupteba in 2023

- C:\juro\yologakib\rihahoy71\waxotobub.pdb

Additional Resources

- Glupteba malware is back in action after Google disruption – Bleeping Computer

- Disrupting the Glupteba operation – Updates from Threat Analysis Group (TAG), Google

- Glupteba Expands Operation and Toolkit with LOLBins And Cryptominer – Malicious Life, Cybereason

- December 2022’s Most Wanted Malware: Glupteba Entering Top Ten and Qbot in First Place - Check Point Blog – Check Point Blog

- First UEFI rootkit found in the wild, courtesy of the Sednit group – ESET, LoJax white paper

- BlackLotus UEFI bootkit: Myth confirmed – We Live Security, ESET

- Glupteba malware hides in plain sight – Sophos News

- DSEFix: Windows x64 Driver Signature Enforcement Overrider – hfiref0x on GitHub

- UPGDSED: Universal PatchGuard and Driver Signature Enforcement Disable – hfiref0x on GitHub

- EfiGuard: Disable PatchGuard and Driver Signature Enforcement at boot time – Mattiwatti on GitHub

- PrivateLoader: the loader of the prevalent ruzki PPI service – Sekoia Blog

- PrivateLoader: The first step in many malware scheme – Intel 471

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh