I’ve plowed through the first wave of AVP (Apple Vision Pro) reviews, and it seems pretty obvious t 2024-2-3 04:0:0 Author: www.tbray.org(查看原文) 阅读量:18 收藏

I’ve plowed through the first wave of AVP (Apple Vision Pro) reviews, and it seems pretty obvious that, at the current price and form factor, it’s not gonna be a best-seller. But I remain a strong believer in Augmented Reality (the AVP is VR not AR, for the moment). As I was diving into the reviews, a little voice in the back of my head kept saying “I once read about what this is trying to be.”

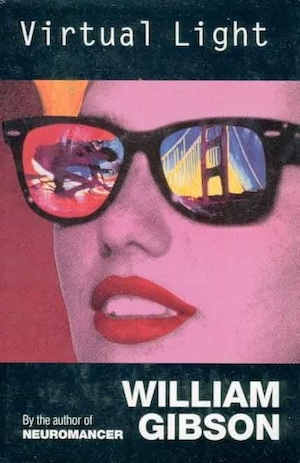

What I was remembering was Virtual Light, a 1993 novel by William Gibson, allegedly set in 2006. It paints a clear picture of a future that includes AVP’s descendants. So I re-read it. Maybe looking back is the way to look forward.

But first… · I wanted to say: It’s a terrific book! If you haven’t read you might really like it. I hadn’t in years and I sure enjoyed the re-read. The people in it are charming, and it’s built around a fabulous physical artifact that drives the plot. No, I don’t mean AR goggles, I mean San Francisco’s Bay Bridge, which in Virtual Light and two subsequent novels, has been wrecked by an earthquake and become a huge countercultural shantytown, one of the coolest venues Gibson has ever invented, and that’s a strong statement. Also, protagonists Chevette and Rydell are two of his best characters; another strong statement.

Anyhow, I don’t think it’s much of a spoiler to say that the AR devices I’m writing about, despite being what the title refers to, are peripheral to the plot. It turns out that one such device contains information that’s secret enough to attract hired killers, skip tracers, and crooked Homicide cops to recover it when it gets stolen; plenty of plot fuel right there.

Quoting · Here are a few out-takes from the book describing the titular technology.

Quote:

Nothing in it but a pair of sunglasses, expensive-looking but so dark she hadn’t even been able to see through them last night.

Quote:

…she took that case out.

You couldn’t tell what it was made of, and that meant expensive. Something dark gray, like the lead in a pencil, thin as the shell of one of those eggs, but you could probably drive a truck over it… She’d figured out how you opened it the night before: finger here, thumb there. It opened. No catch or anything, no spring… Inside was like black suede, but it gave like foam under your finger.

Those glasses, nested there. Big and black. Like that Orbison in the poster… She pulled them from the black suede… They bothered her … they weighed too much. Way too heavy for what they were, even with the big earpieces. The frames looked as though they’d been carved from slabs of graphite.

She put them on. Black. Solid black.

“Katharine Hepburn.” Skinner said.

Quote:

Warbaby wore a black Stetson set dead level on his head, the brim turned up all the way around, and glasses with heavy black frames. Clear lenses, windowpane plain.

Quote:

“You date you some architects, some brain-surgeons, you’d know what those are… Those VL glasses. Virtual light.”

“They expensive, Sammy Sal?”

“Shit, yes. ’Bout as much as a Japanese car… Got these little EMP-drivers around the lenses, work your optic nerves direct. Friend of mine, he’d bring a pair home from the office where he worked. Landscape architects. Put ’em on, you go out walking, everything looks normal, but every plant you see, every tree, there’s this little label hanging there, what its name is. Latin under that…”

Quote (at a crime scene with Warbaby and Freddie):

Rydell noticed the weight as he slid them on. Pitch black. Then there was a stutter of soft fuzzy ball-lightning, like what you saw when you rubbed your eyes in the dark, and he was looking at Warbaby. Just behind Warbaby, hung on some invisible wall, were words, numbers, bright yellow. They came into focus as he looked at them, somehow losing Warbaby, and he saw that they were forensic stats.

“Or,” Freddie said, “you can just be here now —”

And the bed was back, sodden with blood, the man’s soft, heavy corpse splayed out like a frog. That thing beneath his chin, blue-black, bulbous.

Rydell’s stomach heaved, bile rose in his throat, and then a naked woman rolled up from another bed, in a different room, her hair like silver in some impossible moonlight—

Rydell yanked the glasses off…

Quote:

“Here. Check it out.” He put them on her.

She was facing the city when he did it. Financial district… “Fuck a duck,” she said, those towers blooming there, buildings bigger than anything, a stone regular grid of them, marching in from the hills. Each one maybe four blocks at the base, rising straight and featureless to spreading screens likke the colander she used to steam vegetables. Then Chinese writing filled the sky.

Hmmm… · What does Gibson’s 30-year-old vision teach us?

The devices are still heavier than you’d like, but light enough to wear all the time out in the real world.

Still expensive.

They look super-cool.

They are transparent while in use.

You can use them to show pictures or share information the way you would today by handing over a phone or tablet.

How you get information into them was as un-solved in 1993 as it is today.

But the real core value is the “A” in “AR” — augmenting an aspect of the real world that you’re looking at. Even if only by hanging text labels on it.

For me, that last point is at the center of everything. I want to be in a park at night and see fiery snakes climbing all the trees. I want to walk into a big-box store and have a huge glowing balloon appear over the Baking Supplies. I want floating labels to attach to all the different parts of the machine I’m trying to fix.

Watching TV, by yourself, on a huge screen, is not the future. Augmenting reality is.

The AVP? Some of its tech constitutes necessary but far from sufficient steps on the way from here to that 1993 vision.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh