read file error: read notes: is a directory 2023-12-16 07:0:28 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:22 收藏

Executive Summary

Malicious actors often acquire a large number of domain names (called stockpiled domains) at the same time or set up their infrastructure in an automated fashion. They do so, for example, by creating DNS settings and certificates for these domains using scripts.

Automation employed by attackers can leave traces of information about their campaigns in various data sources. Security defenders can find these traces in locations such as certificate transparency logs (e.g., certificate field reputation or timing information) and passive DNS (pDNS) data (e.g., infrastructure reuse or characteristics).

Leveraging these crumbs of information, we built a detector to identify stockpiled domains. The two main advantages of detecting stockpiled domains are expanding coverage of malicious domains and providing patient-zero detections as attackers stock up on domains for future use.

To detect stockpiled domains, we engineered over 300 features to process many terabytes of data and billions of pDNS and certificate records. We used a knowledge base of millions of malicious and benign domains to calculate certificate and pDNS reputation and to train and test a Random Forest machine learning algorithm.

As of July 2023, our detection pipeline has found 1,114,499 unique stockpiled root domain names and identifies tens of thousands of malicious domains weekly. Our model, on average, found stockpiled domains 34.4 days earlier compared to vendors on VirusTotal. The success of our approach emphasizes the need to combine multiple large datasets, such as passive DNS and certificate logs, to detect malicious campaigns.

The stockpiled detector continuously picks up a wide variety of scam, phishing, malware distribution, C2 and other campaigns. Some of these phishing campaigns target the largest software companies, online retail shops, banks, streaming services and more. In this article, we share both large campaigns leveraging thousands of domains and small campaigns involving just a few domains.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection against stockpiled domains by leveraging our automated classifier in multiple Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall cloud-delivered security services, including DNS Security and Advanced URL Filtering.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | DNS, Malicious Domains, Cybercrime |

Table of Contents

Overview of the Domain Wars

The Misadventures of Lisa and the Puppy Scam Site

Scam Sites in the Real World

Early Detection of Malicious/Phishing Domains

Detecting Stockpiled Domain Names

Certificate-Specific Features

Domain-Specific Certificate Features

Certificate Reputation and Aggregation Features for Various Certificate Fields

Lexical Features for Domains

pDNS Reputation and Aggregation Features

Aggregate Features for Certificates and pDNS

A Malicious Redirection Campaign

A European Postal Phishing Campaign

A USPS Phishing Campaign

A High-Yield Investment Scam Campaign

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Indicators of Compromise

Additional Resources

Overview of the Domain Wars

In our previous article on fast fluxing, we described how, over time, techniques used by cybercriminals evolved into the domain wars. This ongoing struggle involves criminals registering many domain names to make it harder for law enforcement to take down their botnets.

The domain wars have spread across all types of online crime, including:

- Phishing

- Scams

- Malware and Potentially Unwanted Program (PUP) distribution

- Adversarial Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

- Distribution of illicit content (e.g., adult pages, gambling and pirated movies)

In this article, we return to our fictional scenario of an interaction between cybercriminals and law enforcement, namely Chief Emilia and Lisa (who is the sister of Bart from our previous episode).

We’ll also discuss multiple campaigns that we’ve detected with our model, as a way of illustrating how we can use various features to improve protection.

The Misadventures of Lisa and the Puppy Scam Site

In our fictional scenario, Chief Emilia saw that even though stricter registration policy changes that researchers had proposed could be useful, these changes would take a long time. These changes also wouldn’t be enough by themselves to solve the domain wars. Thus, she created a research team to collect data about malicious domain names and to develop detectors to identify them.

In the meantime, our budding cybercriminal Lisa had an evil plan. Lisa hasn’t always been evil. In fact, she was a very good-hearted person. But her parents never let her have a puppy, and slowly, she turned sour.

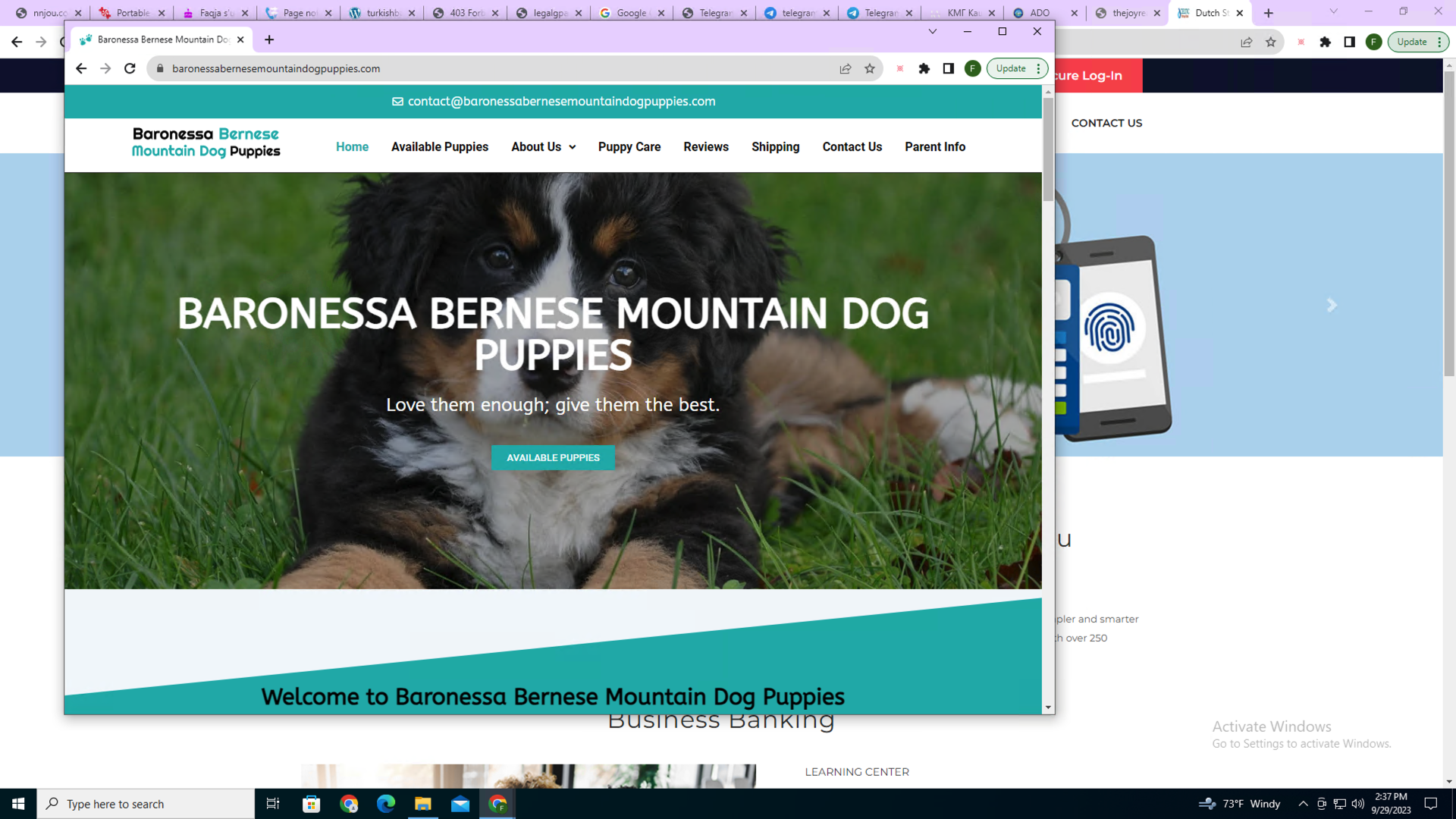

One day, Lisa decided that if she couldn’t have a puppy as a kid, then no other kids could. She began her descent into evil by launching puppy scam websites. Figure 1 shows a real-life example of a puppy scam site.

She started this endeavor by stockpiling a bunch of domain names and cutting together content from real puppy web shops but with fraudulent email addresses, phone numbers and payment sites. (We call these domains registered by the same actor for use in malicious campaigns stockpiled domains.)

Unfortunately for Lisa, Emilia’s team has long been monitoring newly registered domains (NRDs), and they have applied extra scrutiny to these domains. Emilia’s team scraped the sites’ content, analyzed registration behavior and discovered the underlying infrastructure. (This is just as we at Palo Alto Networks pay special attention to NRDs, finding many malicious ones). As a result, Lisa’s scam websites were swiftly found and taken down.

Lisa was determined to succeed. So, before launching the puppy scam campaigns, she started aging domain names used for the websites. As Emilia monitored various scam campaigns, she quickly caught on to the tactic of strategically aging domains (see our research on aged domains) and set her team to watch for when dormant domains get activated.

To evade having her sites scraped by Chief Emilia’s team, Lisa employed a variety of tactics. These included cloaking (showing benign content to suspected crawling bots) and user targeting (showing malicious content only to specific users).

Researchers have shown that cybercriminals use various cloaking and user-targeting techniques, which pose a significant challenge to detect malicious domains. Palo Alto Networks inspects web traffic inline, ensuring we block malicious websites even if they leverage cloaking or user-targeting practices.

Inline detection has its limitations, so Emilia’s team set out to combine a variety of large datasets (including certificate logs and pDNS) to train a machine learning model. This model can find malicious domains leveraging similar automation or infrastructure, or that the same criminal group owns.

Ultimately, it became tough for Lisa to maintain her scam campaigns without getting caught.

One day, while looking at a real web shop that sold puppies, she saw one that looked exactly like the one she wanted as a little girl. She suddenly realized all the evil she had done and decided to give up her life of crime. She adopted the puppy as an adult and joined Emilia’s team to fight cybercrime to undo some of her wrongdoing.

Scam Sites in the Real World

Unfortunately, not all cybercriminals have turned their life around, so we have plenty of similar examples to examine in the real world. Figure 1 shows a real-life puppy scam website (baronessabernesemountaindogpuppies[.]com) and how our detection model gives an advantage in detecting this scam.

Threat actors registered this site on April 21, 2023. Our stockpiled detector first flagged it on April 24, 2023. Two days later, one vendor on VirusTotal marked it as malicious. Then on Aug. 22, 2023, volunteers on a scam-hunting website Artists Against 419 marked it as a scam site.

Early Detection of Malicious/Phishing Domains

Fighting the domain wars is a global community effort where we lean on previous work by academic researchers, law enforcement, cybersecurity professionals, policymakers and volunteers. Researchers in the past have shown that WHOIS and pDNS data are useful for finding malicious domain names registered in bulk.

More recently, researchers looking into certificate datasets discovered they can use these datasets to find stockpiled domains (potentially independent of registration time) where certificates were set up similarly because the criminals likely used automated scripts. Closest to our work is research by AlSabah et al., where the authors looked at both certificate transparency logs and pDNS to identify phishing domains.

Detecting Stockpiled Domain Names

Recognizing that automation can leave us crumbs of information in different datasets, we extracted features from certificate transparency logs, pDNS data and domain name strings that our detector can use to find malicious domain names. Browsers enforce certificate transparency to monitor and audit certificates to make it harder for cybercriminals to use malicious certificates (e.g., when a certificate authority is compromised).

We collect millions of certificates and domains every day from multiple transparency log servers that maintain immutable records of certificates. Similarly, pDNS is a database of DNS request-response pairs passively collected from all over the world (e.g., when users access various web resources or send emails). Our pDNS database consists of billions of DNS records daily.

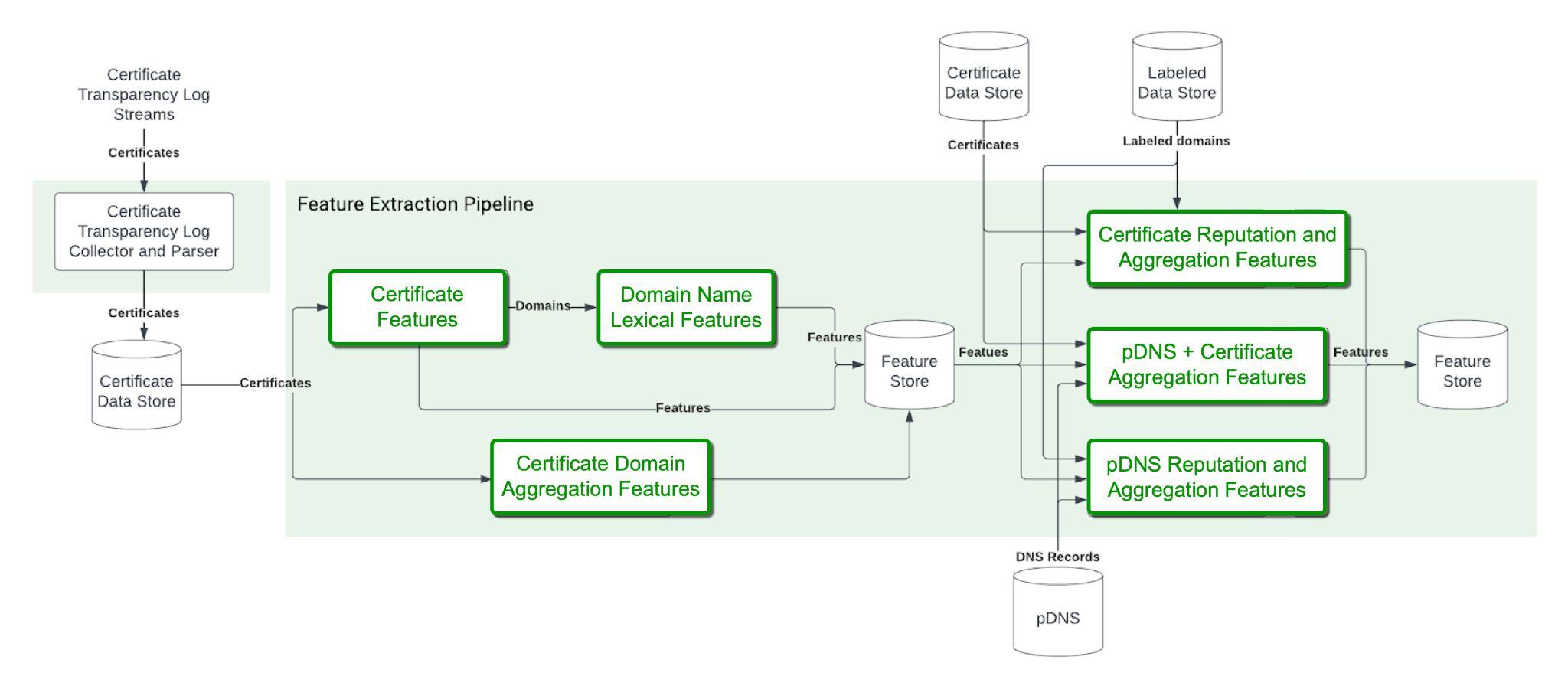

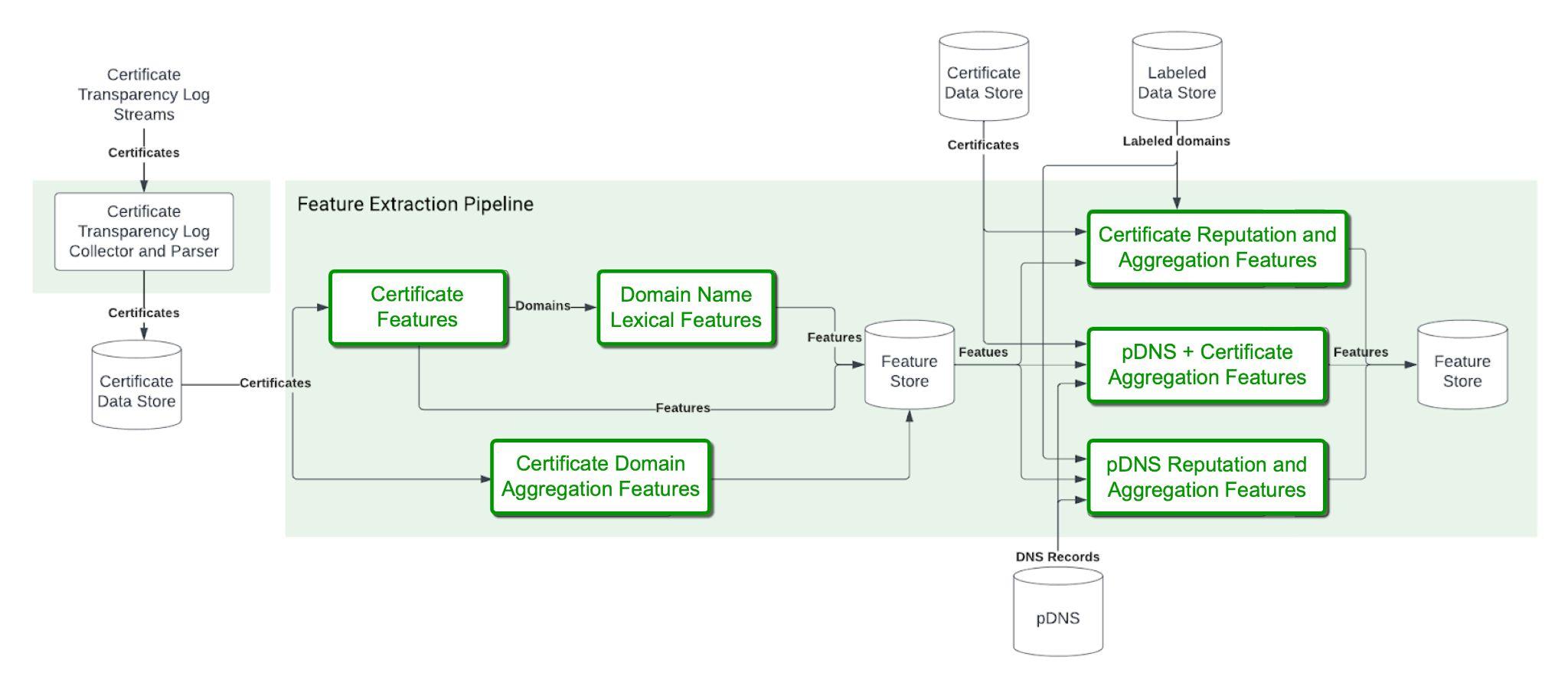

From these datasets, we collect the following six categories of features as shown in Figure 2.

- Certificate Features

- Domain Name Lexical Features

- Certificate Domain Aggregation Features

- Certificate Reputation and Aggregation Features

- pDNS and Certificate Aggregation Features

- pDNS Reputation and Aggregation Features

Then we follow a series of steps to gather further information.

These features include, for example, the validity length of the certificate or the number of root domain names in the certificate. When cybercrooks automate their processes, they might not think to change these details.

Domain-Specific Certificate Features

These features include, for example, the number of certificates and issuers we see for a domain name, which would signal that their owners treat them similarly.

Certificate Reputation and Aggregation Features for Various Certificate Fields

For example, this category includes the proportion of malicious domain names or the distribution of words for specific fields of certificates. We compute reputation scores for certificate fields (e.g., validity length, seen time, not before field and fingerprint). Certificate reputation features help our classifier understand certain field values commonly set by malicious operations.

From the domain name itself, we calculate features like the randomness of the name, the number of words, encoding of the top-level domain (TLD), and whether there is a brand name in the domain name. These features help us capture whether a malicious campaign is targeting a specific set of brands, or if the same algorithm generated the domain names.

pDNS Reputation and Aggregation Features

From pDNS we calculate features like the known malicious and benign proportions of domains and the average domain age or the number of certificates for an IP (or a /24 subnet). PDNS reputation helps us understand more about the shared infrastructure of stockpiled domain names.

Aggregate Features for Certificates and pDNS

These features include, for example, the number of IPs of all the domains in a certificate. Aggregating across multiple data sources (e.g., certificates and pDNS) is essential to understanding the deeper connection between certificate setup and the infrastructure of stockpiled domain names.

After generating features from domain names, certificate logs and pDNS, we train a Random Forest machine learning classifier to predict stockpiled domain names. We leverage our extensive knowledge of millions of malicious and benign domain names as labeled data for training and fine-tuning the classifier for high precision.

Our classifier can achieve 99% precision with 48% recall, even though many of the malicious domains might not be stockpiled or cybercriminals might not leave traces of information in certificate logs and passive DNS data.

Our detection pipeline has found 1,114,499 unique stockpiled root domain names since July 2023, identifying tens of thousands of malicious domains weekly. Other content and behavior analysis-based detectors later identified 45,862 malware, 8,989 phishing and 844 C2 domains among the stockpiled domains.

Our model caught stockpiled domains on average 34.4 days earlier than vendors on VirusTotal. We expect the average delay to grow as other detectors find already identified stockpiled domains.

Our stockpiled detector picked up a variety of campaigns including scams, phishing, malware distribution and C2. Below, we share a few interesting campaigns that our stockpiled detector was able to detect early.

A Malicious Redirection Campaign

Our detector captured more than 9,000 registered domains that were part of a malicious redirection campaign, for example:

- Whdytdof[.]tk

- Pbyiyyht[.]gq

- Rthgjwci[.]cf

- Cgptvfjz[.]ml

VirusTotal vendors were only able to mark 31.7% of these domains as malicious. Even when they found a domain to be malicious, our detector was capable of finding them 32.3 days earlier on average.

Perpetrators rarely set up such a large campaign without leaving some valuable information for our machine learning model. Even though these domains use Cloudflare, which makes pDNS-based identification challenging, we can follow other trails.

In a recent example, perpetrators randomly generated domains using low-quality TLDs. Also, all the domains had the same validity length for their certificates. And while their activation dates are different, perpetrators activated them all fairly recently.

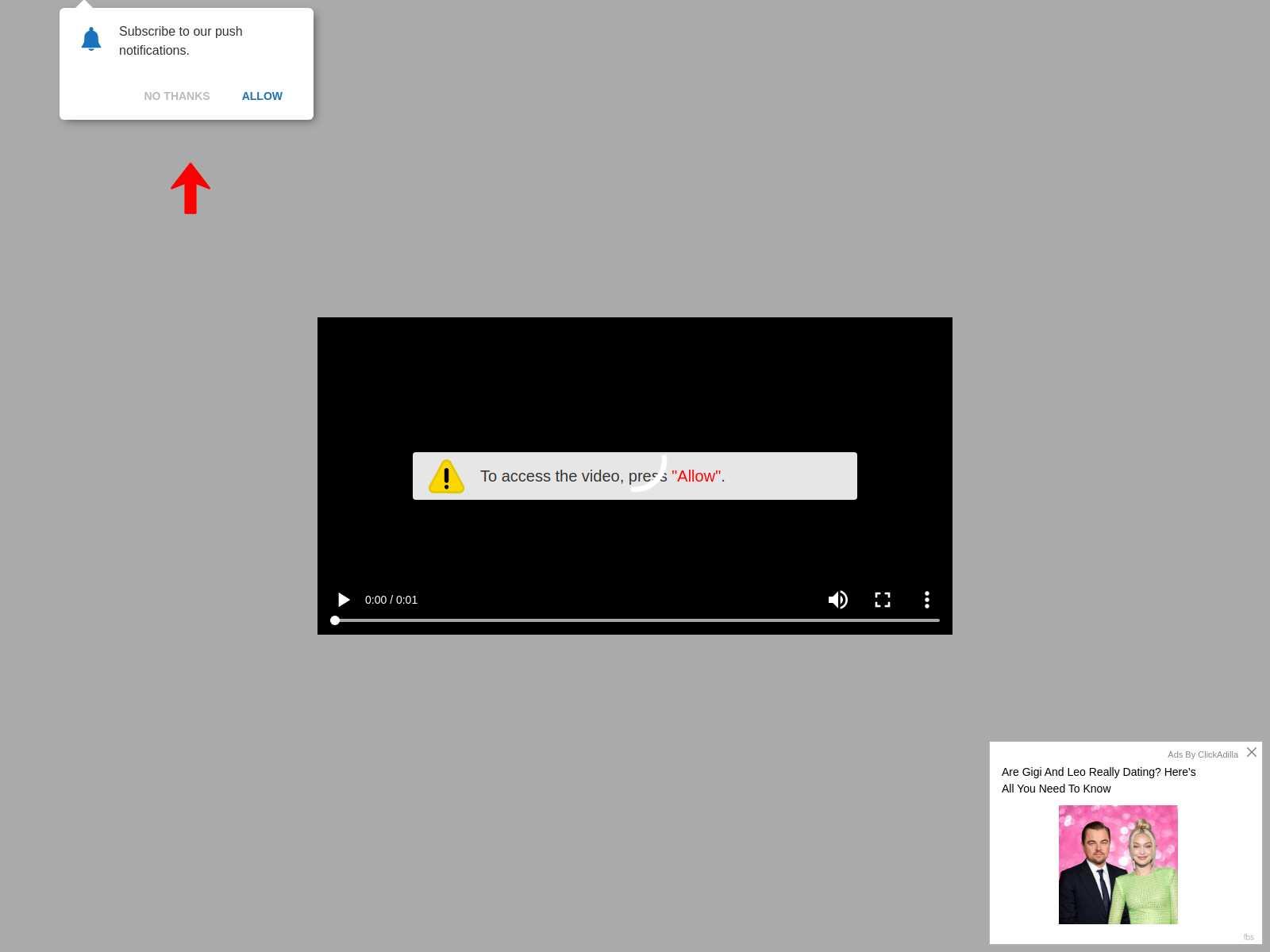

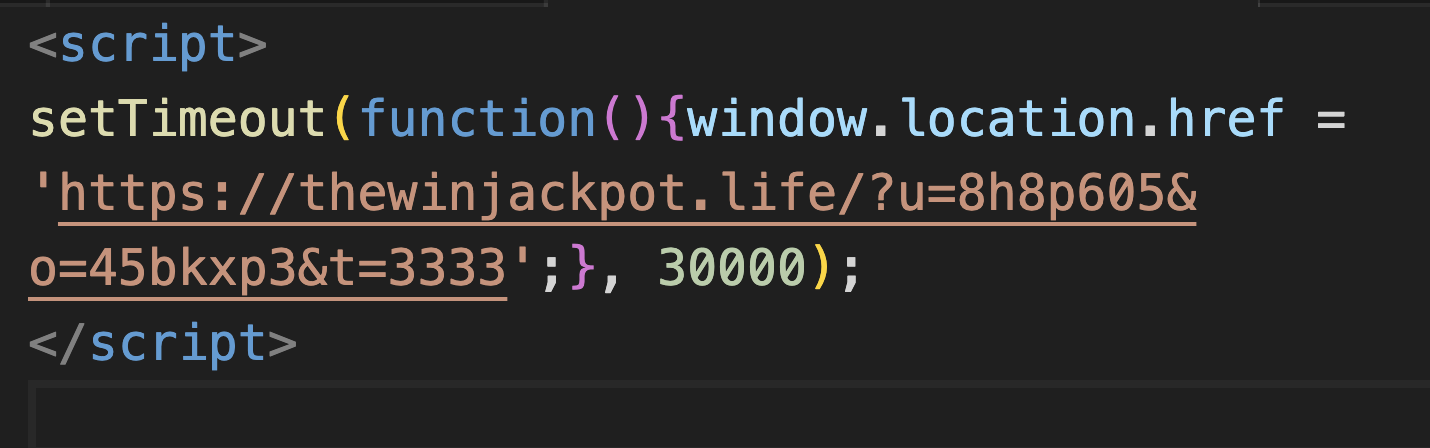

In this campaign, victims are redirected to different websites before reaching a landing page, which is usually an adware or a scam page. For example, Figure 3 shows a screenshot of the final payload received by our crawler after redirections.

In both cases, our crawler was redirected to a fake notification scam with clickbait. A fake warning message was displayed to trick people into allowing an attacker-controlled website to send browser notifications. Additionally, both pages have a clickbait advertisement at the bottom of the website.

Further analysis shows that all these hostnames redirected users to one of two hostnames (i.e., thewinjackpot[.]life and winjackpot[.]life). From the visual analysis of the content of a few detected hostnames, we found that a URL of these two hostnames was assigned to windows.location.href with a timeout (shown in Figure 4). We surmise the campaign owner likely owns both these hostnames, and they later redirect victims to other websites.

A European Postal Phishing Campaign

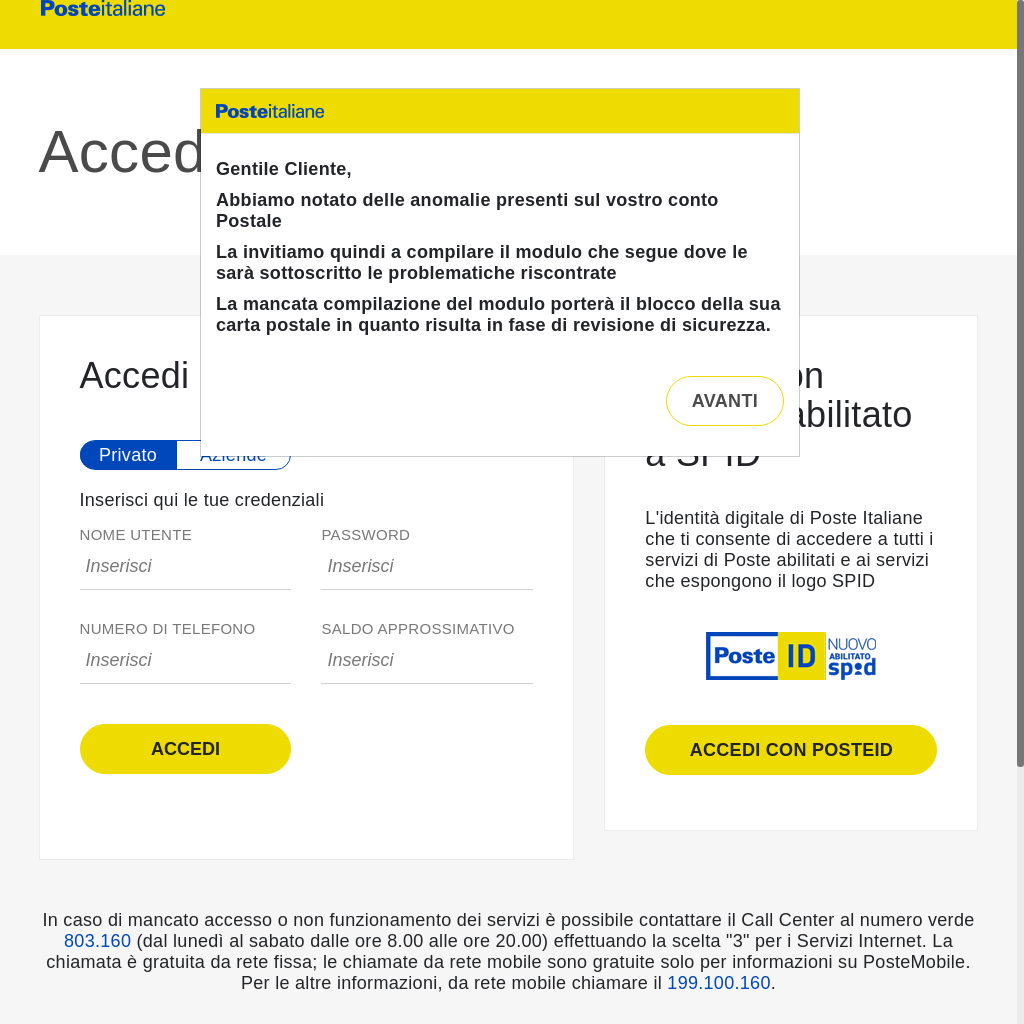

In a postal phishing campaign targeting Italian- and German-speaking users, the phishing page harvested victims’ login credentials. Our detector found a group of related domains.

Vendors on VirusTotal marked only two out of our four example domains as malicious:

- Abschlussschritte-info[.]com

- Aksunnatechnologies[.]com

- 222camo[.]com

- Rothost[.]best

Abschlussschritte-info[.]com was registered on June 2, 2023, and our detector found it to be malicious ten days later, on June 12, 2023. We only saw VirusTotal vendors detecting it two months later, on Aug. 11, 2023.

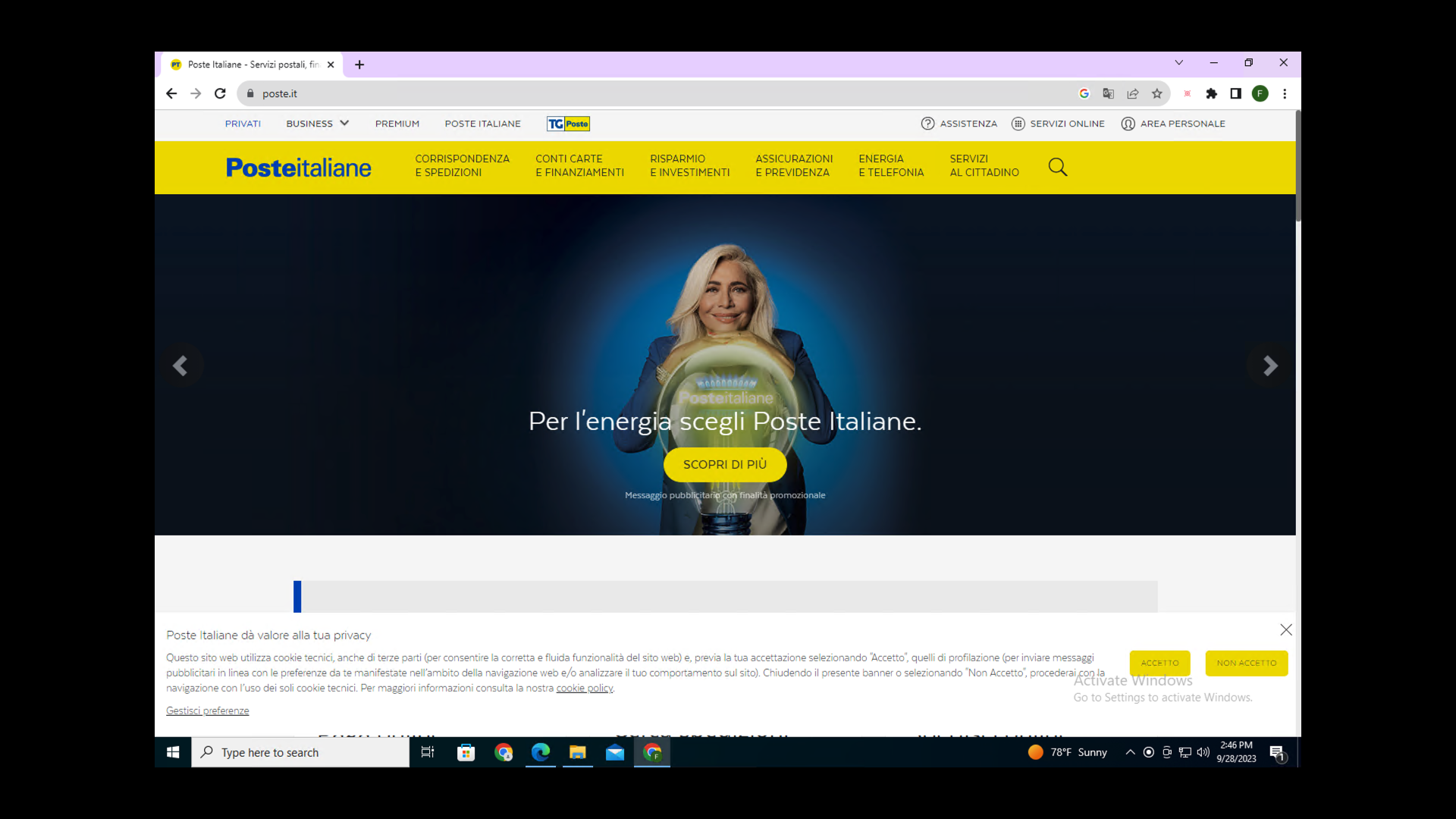

Figure 5 shows what the original webpage poste[.]it looks like.

Figure 6 is a screenshot of the phishing domain 222camo[.]com that is impersonating the original website.

These four domains clearly had the same content and were part of the same campaign. However, there were a few signals related to automation for our detector to use.

Although these domains had the same validity length, they were registered on vastly different dates and used different IP addresses. Thus, our model mainly relied on certificate field-based and pDNS-based reputation features to identify the domains in this campaign.

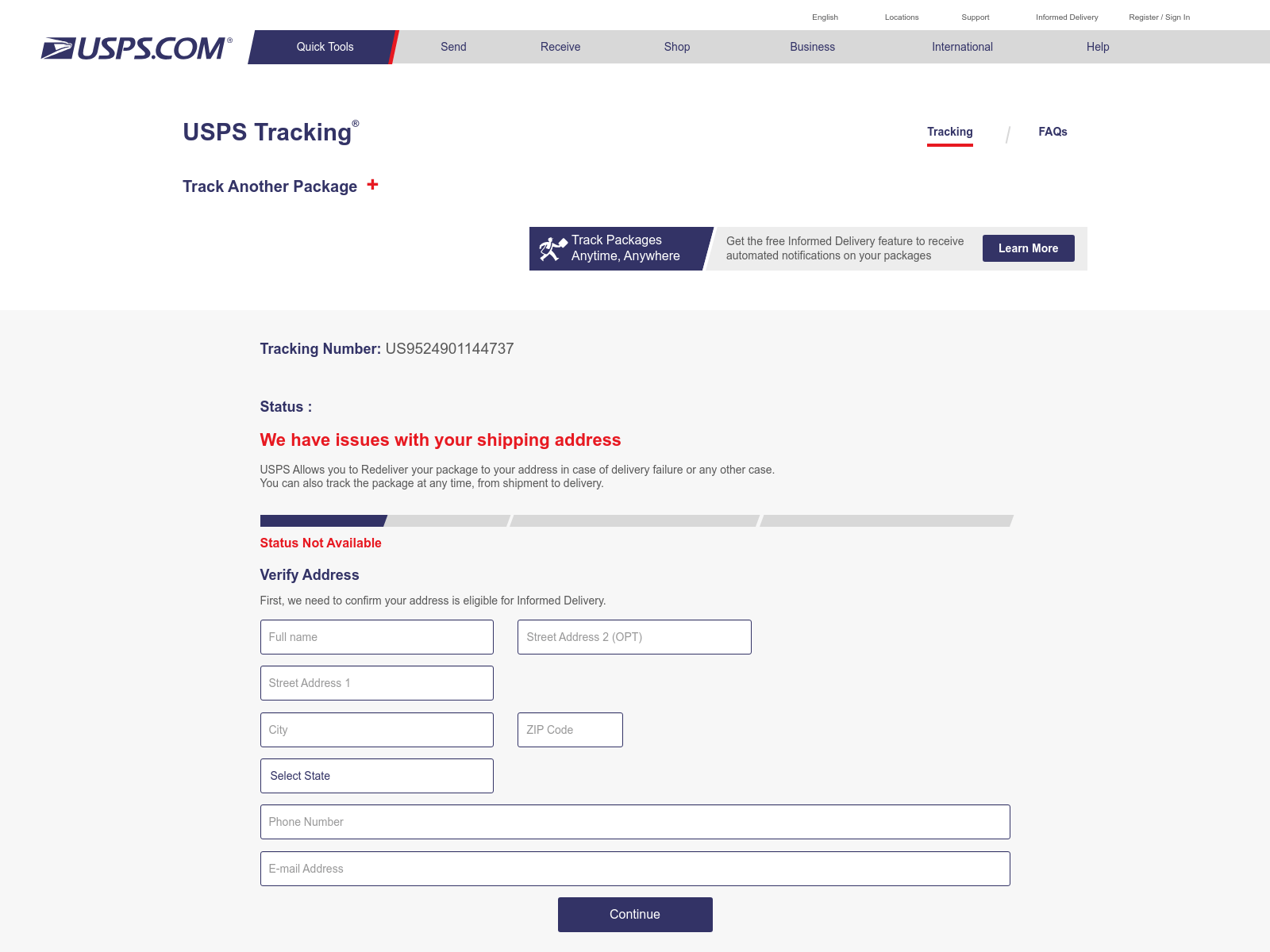

A USPS Phishing Campaign

Our detector caught a campaign impersonating the United States Postal Service (USPS) where more than 30 domains (including the following examples) are used to host the same website shown in Figure 7:

- Delivery-usps[.]vip

- Delivery-usps[.]wiki

- Delivery-usps[.]ren

These domains are registered under only four certificates. Our stockpiled domain detector caught all these domains before VirusTotal first detected them. We detected some of these domains days (e.g., usps-redelivery[.]art – 3 days) or weeks (e.g., usps-redelivery[.]live – 2 weeks) ahead of other vendors.

These domains were registered in the time span between June 17, 2023, and Aug. 28, 2023, and the domain certificates were obtained on the same day of registration. The aggregation of domains into a few certificates and the correlation to domain creation time suggests that threat actors created these domains with some level of automation. This automation allowed us to connect the dots and detect all of these malicious stockpiled domains.

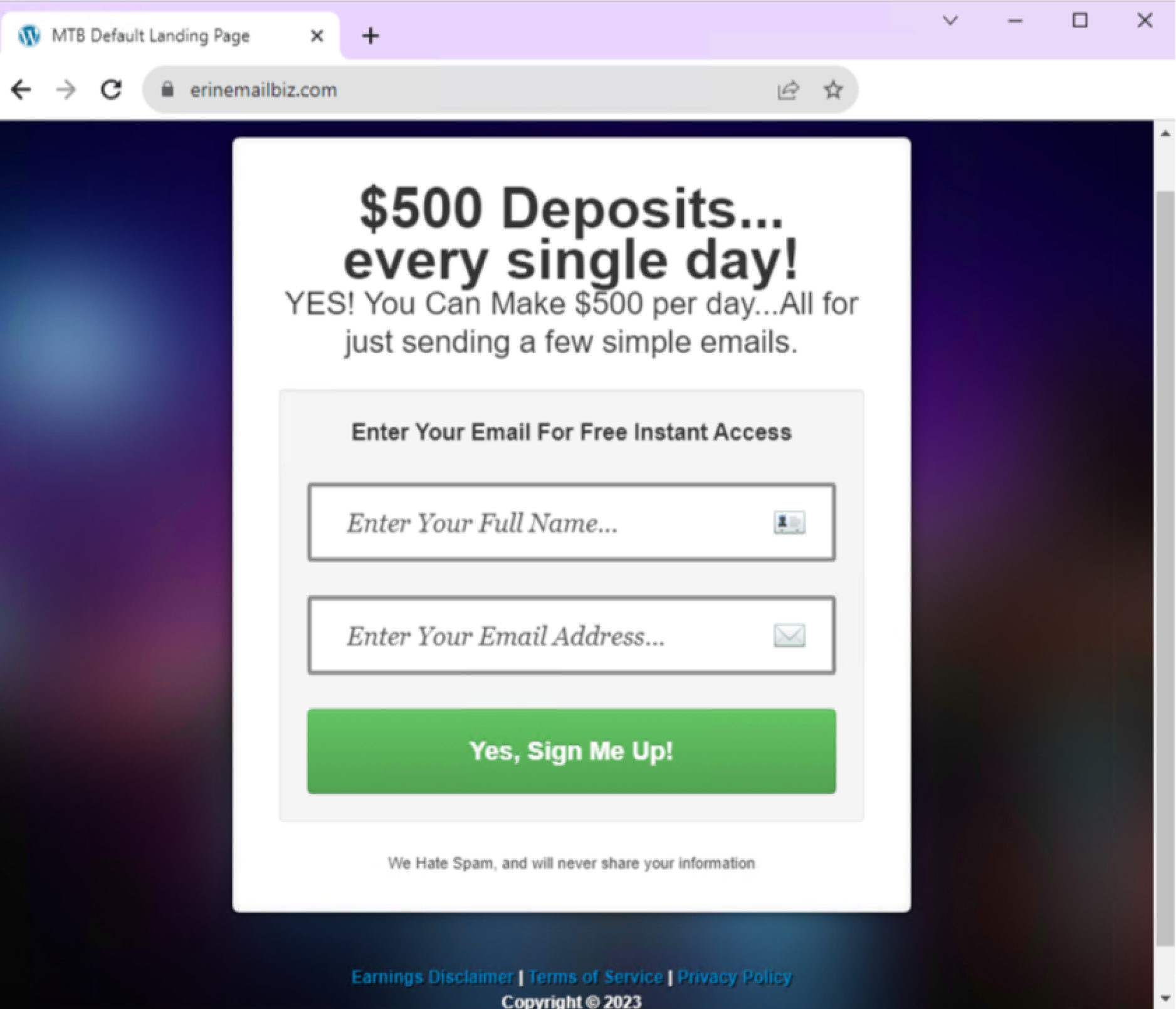

A High-Yield Investment Scam Campaign

One of these campaigns consisted of more than 17 domains focusing on high-yield investment scams. In these campaigns, scammers try to convince users that in return for a small initial investment, they would earn a lot of money.

The following are a few example domains in this campaign:

- Erinemailbiz[.]com

- Natashafitts[.]com

- Makemoneygeorge[.]com

- Julieyeoman[.]com

While VirusTotal vendors found 12 out of 17 of these domains, on average they found them 34.7 days later than our detector.

When criminals set these domains up for their malicious campaigns, they left crumbs of information. For example, all the domains had the same validity length for their certificates, and they used the same IP address. While their registration dates are different, and they had more than one registrar, they were all newly registered domains.

At first, customers will be presented with a page (shown in Figure 8) that asks for very little. Give us your name and email address in return for earning $500 deposits. What is there to lose, right?

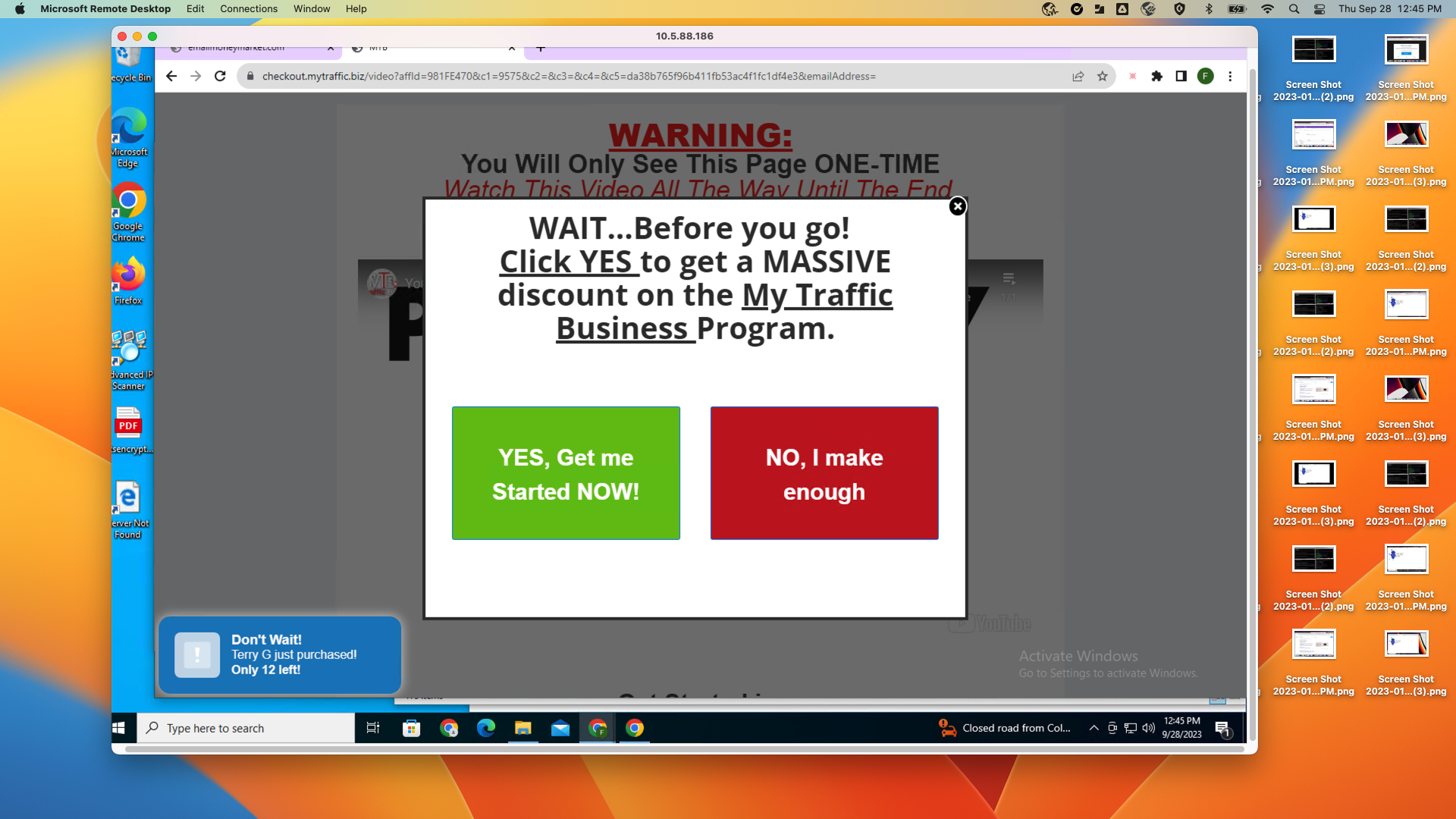

After filling out the information, victims will be redirected to another page to double-check if they’re ready to be tricked.

People who fill out the information and click the submission button will be redirected to checkout.mytraffic[.]biz, as shown in Figure 9. On this page, victims are asked if they want a massive discount. But when they click “Yes,” they’re redirected to the final landing page.

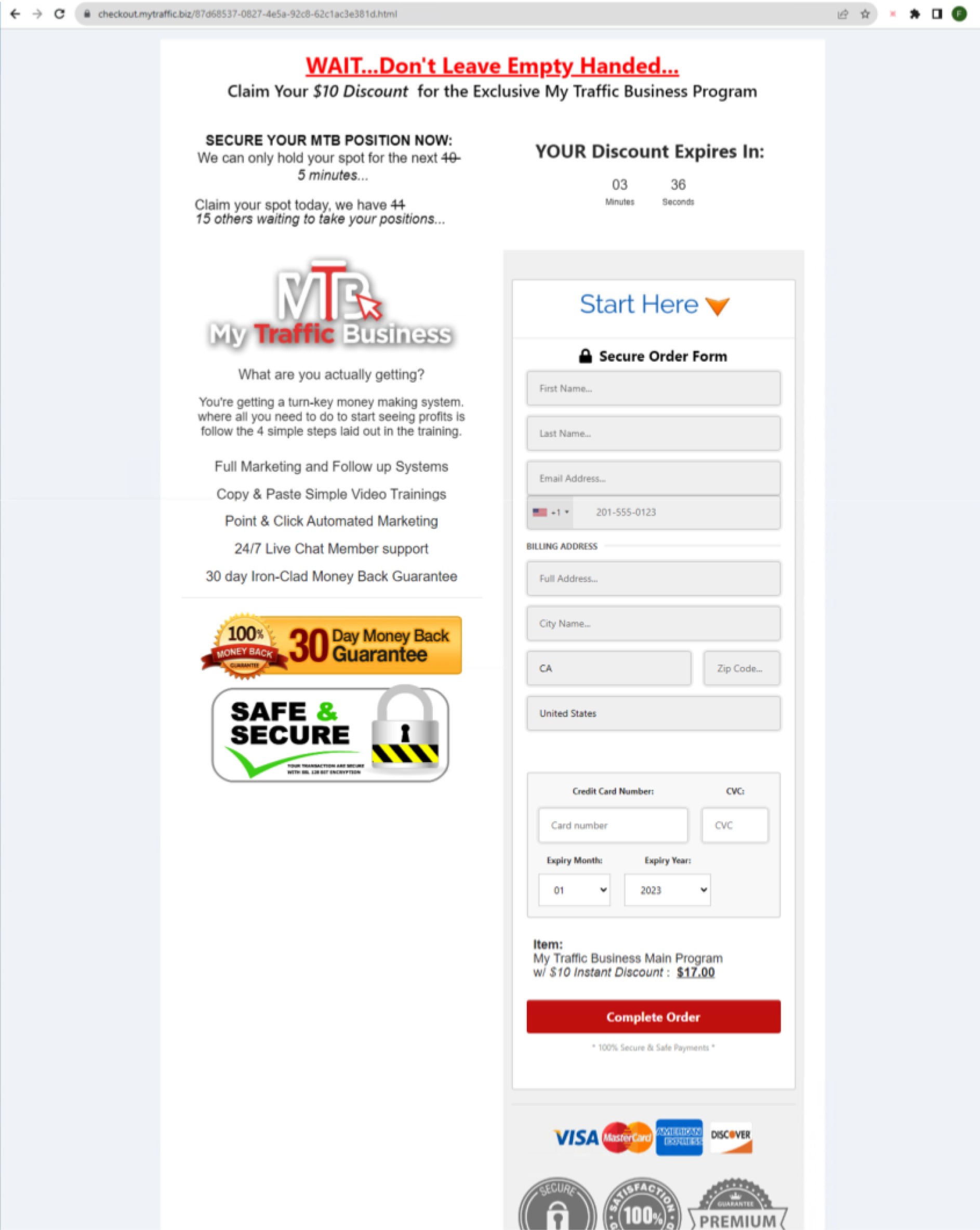

Finally, the victims are redirected to the landing page on checkout.mytraffic[.]biz (shown in Figure 10). The page checks every checkbox for a phishing page:

- The offer is too good to be true.

- There’s a count to hasten people into filling out their information.

- The page also indicates that other people are waiting to take the offer.

- The page is packed with big logos signaling that the page is secure and that there’s a 30-day money-back guarantee.

We hope not many people filled in their credit card information at the bottom.

Conclusion

As the domain wars unfolded, cybercriminals started to automate their infrastructure setup. However, bulk domain registration and infrastructure automation can leave crumbs of information that allow us to detect stockpiled domains. The success of our approach emphasizes the need for security defenders looking to improve their detection to combine multiple large datasets, such as pDNS and certificate logs, to uncover malicious campaigns.

Our high-precision, machine learning-based detector processes terabytes of certificate and DNS logs to discover thousands of stockpiled domains weekly. Our detection pipeline has uncovered a wide variety of different types of campaigns earlier than VirusTotal vendors, and we also found domains that were not detected by others.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection against stockpiled domains by leveraging our automated classifier in multiple Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall cloud-delivered security services, including DNS Security and Advanced URL Filtering.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank George Jones, Arun Kumar, Alex Starov, Lysa Myers, Bradley Duncan, Erica Naone and Jun Javier Wang for their invaluable input on this post.

Indicators of Compromise

Puppy Scam Example Domain

- Baronessabernesemountaindogpuppies[.]com

Malicious Redirection Campaign Domains

- Whdytdof[.]tk

- Pbyiyyht[.]gq

- Rthgjwci[.]cf

- Cgptvfjz[.]ml

- Thewinjackpot[.]life

Postal Phishing Campaign Domains

- Abschlussschritte-info[.]com

- Aksunnatechnologies[.]com

- 222camo[.]com

- Rothost[.]best

A Sample of USPS Phishing Campaign Domains

- Delivery-usps[.]vip

- Delivery-usps[.]wiki

- Delivery-usps[.]ren

- Usps-redelivery[.]art

- Usps-redelivery[.]live

USPS Phishing Campaign Certificate SHA-1 Fingerprints

- 18:FF:07:F3:05:A7:6A:C2:7A:38:89:C5:06:FD:D7:B8:D9:06:88:AB

- 89:29:97:5E:E9:F7:14:D9:95:16:9B:B3:74:33:0C:7B:D0:8F:98:30

- B6:74:45:84:0C:FF:81:05:C2:28:0F:EF:91:23:D8:A0:E8:ED:3A:2E

- 6A:21:31:8B:F4:0A:04:40:FA:37:46:15:A3:CE:1F:0A:C5:0A:93:C3

High Yield Investment Scam Campaign Domains

- Erinemailbiz[.]com

- Makemoneygeorge[.]com

- Natashafitts[.]com

- Julieyeoman[.]com

- Checkout.mytraffic[.]biz

Additional Resources

- Fast Flux 101: How Cybercriminals Improve the Resilience of Their Infrastructure to Evade Detection and Law Enforcement Takedowns — Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh