A group of policemen in body armour and helmets burst into a mosque during prayer, r 2023-12-15 23:33:56 Author: www.bellingcat.com(查看原文) 阅读量:19 收藏

A group of policemen in body armour and helmets burst into a mosque during prayer, released tear gas and shoved men, women and children to the ground. This event in the Moscow suburb of Kotelniki in July was widely reported in the Russian press. The disturbing footage was first shared on a popular xenophobic Telegram channel.

It was one of dozens of raids targeting migrant workers in Russia this year. A large-scale campaign against illegal migrants known as ‘Nelegal-2023’ was carried out by law enforcement in two stages in June and October. Russia’s Interior Ministry told the newspaper Izvestiya last month that over 15,000 migrants have been deported from the country in the course of the campaign.

With the help of our interns, Bellingcat collected and analysed imagery of these raids and detentions shared on social media channels. We found 60 videos and photos depicting 50 raids between May and August, the chief period of focus of our research. This was a particularly active period which included the first stage of Nelegal-2023, 29 of which we were able to geolocate.

We also discovered extensive footage of subsequent events during and after the second stage of Nelegal-2023 in autumn, though this period was not monitored as closely by our researchers. Overall we found 14 videos which depict law enforcement committing violence against migrants between May and November, 13 of which could be geolocated. This is far from an exhaustive survey of the available open source evidence.

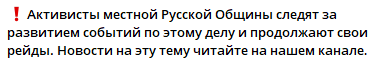

A key source of footage of these raids was a series of xenophobic Telegram channels, such as Многонационал (‘Multinational’), Русская Община (‘Russian Community’). The same footage also surfaced on other xenophobic channels including Северный Человек (‘Northern Man’) and smaller far-right groups. Bellingcat has chosen not to link to these channels to avoid amplification.

As their names suggest, these channels have strongly nationalist positions and have shared videos of police detentions of migrants since at least 2019. Similar examples could occasionally be found on smaller local interest Telegram channels focused on particular districts of large cities.

We also found indications that members of these channels don’t just comment approvingly on police raids against labour migrants in Russia – they are actively involved in instigating these raids. They regularly publicise events or the addresses of places where migrants – or those they perceive to be migrants – gather with a view to alerting law enforcement. When police raids follow, members of these xenophobic groups are on the scene with their smartphones to record detentions of migrants, which they share with their hundreds of thousands of approving followers. Russia’s Ministry of the Interior did not respond to Bellingcat’s requests for comment.

Far-right anti-migration activism has risen drastically since the start of 2023, states Vera Alperovich, an expert with the Moscow-based SOVA Centre, an NGO which monitors nationalism and racism in Russia. “No longer limiting themselves to the role of the critical observer, nationalists have started to create newsworthy events themselves, joining a battle in the name of local residents”, she wrote in a monitoring report for SOVA Centre in June.

Gyms, Mosques and Cafes

Apart from the aforementioned case of the raid on the mosque in Kotelniki, several other videos of detentions of migrants have surfaced on social media since the first stage of Nelegal-2023 began.

Most of the raids analysed by Bellingcat took place in Moscow or cities in the surrounding Moscow Region. Still, there were also a few cases in Krasnodar, Samara, St Petersburg, Yekaterinburg and the Siberian cities of Chelyabinsk, Blagoveshchensk and Irkutsk. These raids have taken place at migrants’ places of work, such as construction sites and markets; their places of residence, such as apartments, hostels and dormitories; and , places for public gatherings, including a Central Asian cafe, gyms, and a football field.

In several cases, the far-right Telegram channels appear to have played a role in inciting the raids.

One such incident on May 28 was recorded extensively from the football field at School No.811 in Moscow’s Mozhaysky District (55.711889 37.400803). That morning, the ‘Russian Community’ Telegram channel shared a video compilation which began with schoolchildren complaining that a group of migrants had forced them off the playground and verbally abused them and their parents. In the same clip the men can later be seen playing football, as a woman can be heard complaining to the camera.

The clip includes close-up footage of men being led away by police, who lay some of the men on the ground and beat them with truncheons. It ends with representatives of the movement on the same football field talking about the successful operation and urging Russians to contact them if they encounter similar problems.

According to the text of the Telegram post, the parents had complained directly to ‘Russian Community’, which filed a complaint with the police with legal assistance. “While our guys on the front are beating the enemy, on the home front, the Russian Community is defending our families” it declares. A few hours later, the channel posted again to claim that 49 migrants had been detained during the event.

These arrests were celebrated by other xenophobic Telegram channels such as ‘Multinational’, which shared two of the same clips of police violence against the migrants at the football field it said was now “free from foreign occupiers”.

A further video shared by the Tajik YouTube channel Bomdod TV on June 1 shows a group of men sitting beside outdoor exercise equipment near the football field as police beat and kick them. The impact of the kicks is audible even though the cameraperson is filming from behind a fence several metres away from the scene.

A survey of the Telegram channel shows that this wasn’t the first time the ‘Russian Community’ had confronted migrants on football fields in Moscow, usually by sending members to ‘have chats’. However, it appears to be the first in which they successfully called on the authorities to help. Two months later, the channel decried ‘persecution’ of the police officers involved after revealing that a complaint had been filed against them.

On July 31, the ‘Russian Community’ turned its attention to two ‘migrant boxing clubs’ in Moscow. In a video shared on its Telegram channel, migrants are made to lie on the floor of the gym with their hands behind their necks. Several of them wear only underwear. They are made to do squat jumps in a line on the tarmac outside. The cameraperson accompanied police on the raid. However, the cameraperson can’t be seen in the video and at no point do they appear in a reflection or move in view of the lens, making it impossible to determine whether they were a civilian or a member of law enforcement.

In contrast to the incident on the football field, ‘Russian Community’ did not claim that any locals had complained about the migrants, simply asserting without evidence that such martial arts clubs attracted ‘criminal elements’. However, this concern about martial arts is only apparent when migrants or those perceived to be migrants are involved. One of the two gyms, in Moscow’s Tagansky District (55.738105,37.666178), is located in the same building as a knife fighting club with a Russian Imperial military coat of arms and the name ‘Patriot’. It did not attract the same scrutiny from the Telegram community.

The same post claimed without evidence that a half and a third of those whose documents were checked by police at the two gyms had violated migration law.

Open source information indicates that riot police raided at least a dozen Central Asian restaurants over June, July and August – during and in the months immediately after the first phase of Nelegal-2023. Most of them were in Kotelniki, 22 kilometres from Moscow. On July 13 the ‘Russian Community’ Telegram channel wrote of raids on four restaurants leading to the detention of 30 people, “one in five of whom was illegal!” A video shows the police forcing the clientele and staff of the Didor Restaurant (55.66047160167306, 37.85544956623931) onto the ground, some of whom they then beat and kick. Didor is a Central Asian restaurant; traditional flat bread can be seen on the tables and the word ‘Didor’ derives from a greeting in Tajik.

Once again, as in the case of the prayer room in the same town and the football field in Moscow, the ‘Russian Community’ claims that the raid took place after complaints by locals. Once again, the cameraman accompanies the police during the raid though they cannot be identified. These clips and others showing the same events were also shared by ‘Multinational’.

Raids also took place at construction sites. On May 21 a post appeared in the ‘Right View’ Telegram channel containing two videos showing what it said were police detentions of migrants in Kotelniki – one showed men fleeing a cafe during a raid, the other an altercation between migrant construction workers and police. This channel is explicitly far-right and proclaims its support for a ‘White Europe’.

The second of these two videos appeared later that day in the Overheard in the Police and National Guard Telegram channel. Geolocation reveals that this second scene in fact took place outside the Lakhta Centre in St Petersburg’s Primorsky District (59.988985, 30.174993).

Two police officers are seen kicking and beating a man as his fellow workers in hard hats and high-visibility jackets stand and watch. They may be construction workers at the nearby Lakhta Centre 2, which will become the tallest skyscraper in Russia upon completion. Soon afterwards the policemen shove him onto a bus packed with other workers as they check passports. The migrant is heard saying that he did not have his documents with him as he had stepped out for lunch, to which a person in civilian clothes replies, “have your lunch at work, not here”.

Two weeks later, the cameraman in a video posted by ‘Multinational’ walks around the same area and complains about a street market where dozens of construction workers are seen buying food. The post garnered over 100,000 views. The very next day, the same channel posted that riot police had raided the area and detained several migrants – a claim backed up in two videos showing the same street. In July, the channel complained about the same area. Raids in September followed; a police officer kicked over boxes of bread, which construction workers scurried to pick up off the ground.

On October 30, Russian police raided an Azerbaijani wedding in the Kurakina Dacha restaurant in St Petersburg and, according to Azerbaijani media, detained five men. CCTV footage from the event uploaded to Telegram shows police beating two of the guests.

More recently, on November 15, police burst into a birthday party at the Fort restaurant in the city of Voronezh and detained a number of Azerbaijani men who were reportedly then requested to attend the military recruitment office. The ‘Multinational’ Telegram channel celebrated both incidents — the post below notes that ‘we need to pay more attention to weddings and birthday parties’. It is not clear whether the channel helped organise the raids. However, there is no evidence that ‘Multinational’ has shown the same scrutiny towards mass events or celebrations by ethnic Russians.

Most of these incidents show some level of coordination between Russian law enforcement and several xenophobic, nationalist online communities that frequently claim to be addressing the concerns of local Russian residents. Bellingcat used reverse image searching of screenshots of these videos and specific keyword searches to establish the origin of these videos. In most cases, we were unable to find these particular pieces of footage shared online earlier than when the aforementioned Telegram channels first posted them.

Bellingcat was also unable to find clear statements from police that they support or monitor these channels. However, the correlation between the xenophobic channels’ reports on ‘migrant activity’ followed by rapid police raids suggests that one exists.

Detentions of migrant workers continue to take place at a large scale across Russia; these channels continue to post about them supportively.

‘Raids at the Request of the Russian Community’

In the first stage of Nelegal-2023 alone, Bellingcat found five instances where police raids immediately followed xenophobic channels posting the location of ‘migrants’.

A large proportion of the videos showing Russian police detentions of migrants were taken from Russian nationalist Telegram channels. The two largest were ‘Russian Community’ and ‘Multinational’, which have 150,000 and 206,000 subscribers respectively. They also openly boast of their ‘coordination with law enforcement’, such as in a July 4 post by the former thanking the police for raids ‘at the request of the Russian community’.

Some closed nationalist Telegram channels also reportedly inform police about gatherings of labour migrants. According to Al Jazeera, the closed group ZOV is one of them and is run by a former staffer at Tsargrad TV, a nationalist media network funded by oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev. The group’s name translates as ‘call’ and refers to three Latin letters that have become symbols of the invasion of Ukraine.

A look at the posts on ‘Russian Community’ and ‘Multinational’ both before the start of Nelegal-2023 and at the time of writing shows that their members are staunch supporters of Russia’s war against Ukraine. For example, they collect donations for the military. ‘Russian Community’s main channel includes the phrase ZOV in its title; the group also runs a channel for occupied Mariupol in Ukraine.

Andrey Tkachuk, the coordinator of Russian Community, set out his vision for Russian migration policy in a video in July. He demanded the institution of a visa regime with Central Asian and South Caucasus states, an end to ‘easy’ acquisition of Russian citizenship after permanent residency and spoke against the existence of informal community organisations for migrants. Tkachuk, who stated that his was not a fascist or far-right movement, said in the same video that ‘there is no such thing as Ukraine’.

Bellingcat found several posts from these groups criticising even small attempts by Russian officials to improve relations with migrant communities.

These groups have also developed conspiracy theories to justify their xenophobia. In an April 23 post on ‘Russian Community’s Telegram account, the movement blamed ‘western security services’ for trying to create a ‘new proletariat’ in Russia to act in their interests: ‘millions of migrants, called by somebody to Russia’. This portrayal of migrants as a ‘fifth column’ can be found in older posts on these Telegram channels.

It is clear from these channels’ posts that they attempt to direct police towards areas where ‘migrants’ congregate – including, as shown above, areas which may be frequented by Russian citizens with origins in Central Asia or the Caucasus, such as mosques and certain restaurants.

For example, on June 21 the Russian Community Telegram channel stated that they were responsible for enforcement discovering two apartments full of ‘migrants’. When some migrants resisted arrest, ‘our guys’ fought them off, claims the channel. However, it is not clear whether ‘our guys’ refers to the police or members of the channel.

The same post called on followers to notify them of the locations of any ‘migrant’ apartments and noted that the Russian Community continues to ‘cooperate with law enforcement bodies’.

And the police appear to be watching. As mentioned earlier, the majority of videos of police raids against migrants occurred in the Moscow suburb of Kotelniki. Here, a Russian Community Telegram post from June 14 claims that ‘according to local activists, the chat is regularly monitored by representatives of the Kotelniki district police’.

The ‘Russian Community’ have also claimed to carry out their own ‘raids’. In some cases they have tried to incite police raids in person, not merely by posting addresses online. One such example can be seen outside the central market of Novosibirsk (55.042847, 82.923846), which was uploaded to the group’s Telegram channel on June 23.

A group of men surround a fruit seller on the street and demand that he show them his documents to prove that he is there legally on the grounds that they are customers. His requests to not be filmed are ignored. They ask him who gave him permission to be there, then accuse him of evading taxes and selling food without a licence.

The leader of the group then takes out his telephone and calls the police on the scene, telling them to come to the spot where he has registered a ‘case of illegal trading’. The accompanying post states that the police did not arrive on the scene at Russian Community’s request – which they cite as evidence that the ‘illegal traders’ have some kind of protection.

The same post containing the video ends with a statement that Russian Community continues to monitor the situation and to carry out ‘our own raids’:

These communities also appear to eager to see their members within the ranks of law enforcement. On September 3, ‘Multinational’ posted a link to two job vacancies in a Moscow police department, promoting it as an opportunity ‘to fight against criminality, including ethnic criminality, and to take part in raids’.

Bellingcat was also unable to find any statements from Russia’s police or Ministry of the Interior about these channels nor whether their employees monitor them.

Russia’s Ministry of the Interior, which is responsible for law enforcement, did not respond to Bellingcat’s requests for comment about whether police used information from the aforementioned Telegram channels or allowed their members to accompany police on raids.

‘Russian Community’ did not respond to Bellingcat’s request for comment. However, an administrator of the ‘Multinational’ Telegram channel called us ‘enemies of Russia’ and said that he refused answer our questions, only to then answer two of them. “We carry out our activities independently from any state structures and there are no employees of any law enforcement agencies among our leadership”, he answered in a Telegram message.

Old Trends, New Alliances

This wave of arrests is far from the first in Russia, which has a history of violent police arrests of labour migrants. However, speculation about the motivation for recent raids abounds, given that they occur against the backdrop of Russia’s war on Ukraine. The Russian journalist Andrei Soldatov writes that ongoing arrests may be a further attempt by the Russian military to replenish its depleted ranks without resorting to a general mobilisation. New decrees in 2022 permit foreign citizens to sign contracts to serve in the Russian military.

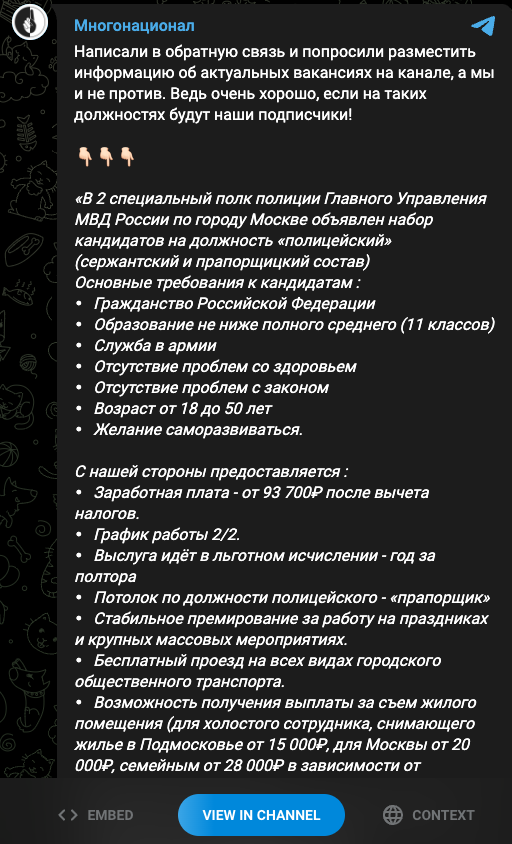

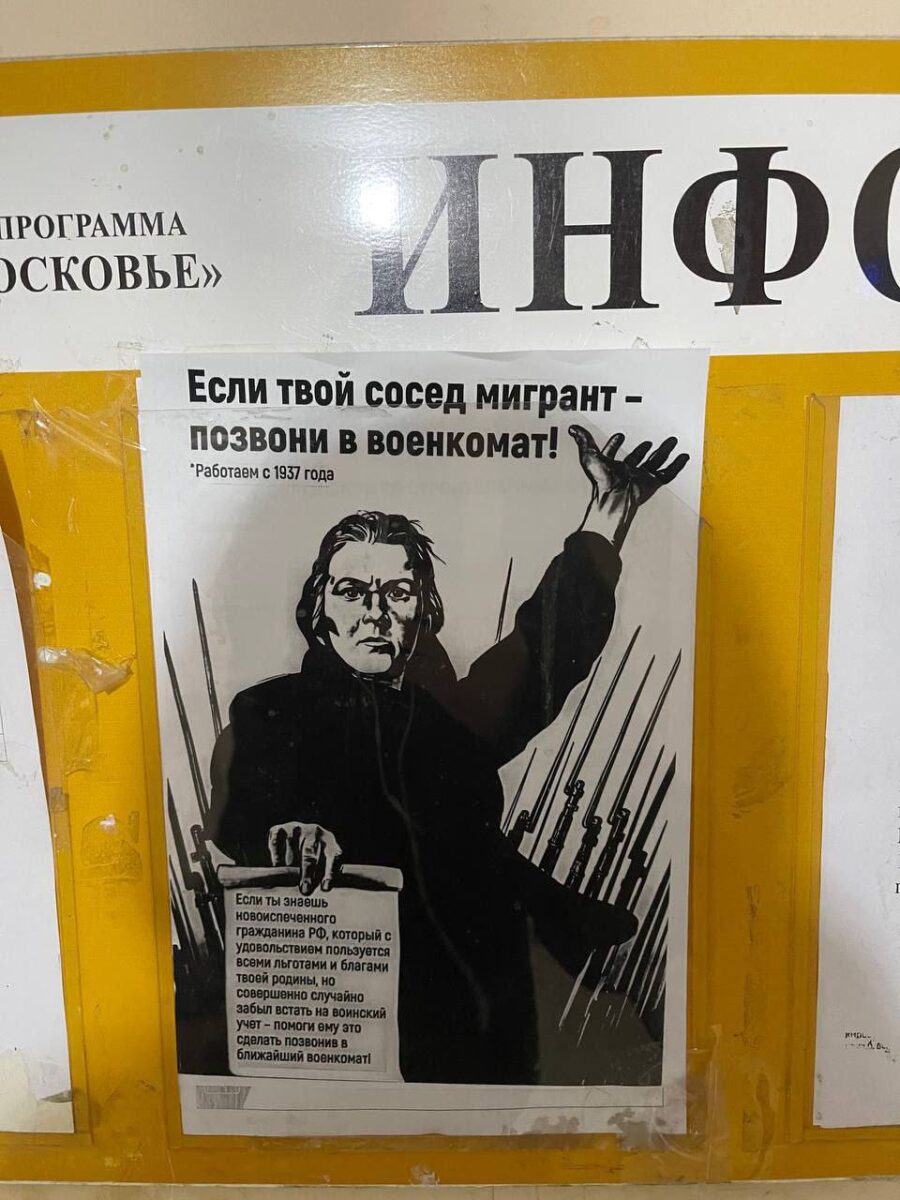

In the case of some channels, the motivation to send ‘migrants’ to fight in Ukraine is more explicit. Below, a flyer circulated by the ‘Northern Man’ Telegram channel repurposes ‘The Motherland Calls’, a famous Soviet propaganda poster from 1941. The poster reads ‘If your neighbour is a migrant, call the military recruitment office!’

Although the text of the Telegram post announces an ‘initiative of the residents of the Moscow region to help the military enlistment office search for illegal migrants‘, the text on the scroll in the poster urges supporters to look for ‘newly-minted citizens of the Russian Federation… who have forgotten to sign up’.

However, Valentina Chupik, an activist and lawyer from Uzbekistan whose NGO defends the rights of labour migrants in Russia, told Bellingcat in an interview that she did not believe conscription was the primary goal for the latest wave of police raids on labour migrants — whatever may motivate such xenophobic channels.

Most labour migrants from Central Asia, she explained, are not Russian citizens. Those men detained during police raids who then receive military summons may be Russian citizens of Central Asian descent or domestic migrants from majority-Muslim areas of Russia, said Chupik. The xenophobic channels’ assumption that those present at Central Asian restaurants or mosques must be ‘illegal immigrants’ suggests that anti-migrant activists do not distinguish between these two groups, she continued.

“What makes this year different is the lower number of migrants in Russia, more violence, and more coordination with the Nazis”, she said. Based on the number of migrants who have appealed to her colleagues for assistance, Chupik says that she knows of around 18,000 detentions of migrants in Russia this year so far — a scale, she says, much lower than the average of 25,000 detentions in the early to mid-2010s. This she attributes in part to the lower number of labour migrants in Russia following the Covid-19 pandemic and the economic disruption following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Yes, there’s coordination”, Chupik remarked. “But the leading role here isn’t played by the Nazi organisations. The police use them to track those places where migrants can be found. The police are lazy; the Nazis are the dependent side here… They are prepared to work with these people for as long as it profits them”, she concluded.

The activities of groups like the ‘Russian Community’ are a good example of the Russian far-right’s adaptation to new political realities, wrote Alperovich, the SOVA Centre expert, in the same report from June. “They position themselves as social, not political movements and declare that they are not interested in fighting for power. They defend conservative morals and Orthodox values but most of their activity is directed at the fight against migrants”.

Maxim Edwards contributed research and reporting. With thanks to Bellingcat’s interns Saliya Khurova, Salima Almazbekova and Darika Taranchieva for their research.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh