2023-10-30 23:21:48 Author: securityboulevard.com(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

Table of Contents

In Q3 of 2023, several high profile attacks against the gaming industry and other large enterprises were carried out by “Scattered Spider”, aka UNC3944, aka Scatter Swine aka, Muddled Libra, aka Roasted 0ktapus aka possibly sometimes BlackCatALPHV or Rhysida, aka a group of globally distributed teenagers…

Attribution is hard in this industry.

While we are using a smidge of humor to draw attention to the dilemma, the reality is trying to fit these types of attacks into a perfect box for the sake of applying the correct label has diminishing returns and can actually lead defenders in the wrong direction. Too much emphasis ends up being applied to the WHO versus the HOW & WHAT (i.e. how they did it, and what TTPs and IOCs do we see). What are the odds that ALL of the attacks carried out by the aforementioned group were worked on by the exact same group of cyber criminal individuals? Our Price is Right answer would be closer to 1% versus 100%.

Readers of this blog will recognize our continued drumbeat on how fluidly cyber extortionists are able to brand shop between known Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) operations or work as unbranded lone wolves (which precipitates the attribution product market label SEO fight). We prefer to avoid the labels, and train our clients and readers on the HOW and WHAT so they can defend themselves. In Q2 2022, when we first started seeing the ‘scattered tactics’ of this group, we focused on one unique TTP that was unique, impactful, and preventable with procedural change (i.e. no technical changes or new security software needed). One of the most common overlapping tactics observed was the skillful social engineering of the IT support desk to subvert, reset or overcome multi-factor authentication. Not only did we consistently see this tactic, but voice recordings from impacted enterprises confirmed that this group was consistently using the same two or three individuals to perform the social engineering. Below are some observed tactics and suggested mitigation strategies that are effective at addressing a major point of ingress:

Reconnaissance [TA0043]

Gather Victim Identity Information [T1589, T1591]: These threat actors gather extensive information about specific employees and the company’s IT support desk functions. This information may include an employee’s role, managers, team members, working hours and frequently used applications. The depth of understanding demonstrated may appear to denote insider collaboration, but to date, no insider collaboration with the threat actors has been proven. A key part of the reconnaissance is to map out how an employee may interact with an internal IT support desk agent. The goal is then to replicate this interaction using social engineering, as a means to bypass multi-factor authentication.

Phishing for Information [T1598]: This threat actor will perform reconnaissance on employees that are candidates for further targeting to determine their technical sophistication and likelihood of being successfully socially engineered.

Initial Access [TA0001]

Phishing [T1566]: The threat actor will target specific employees that have access to common applications that contain sensitive data such as CRM applications, cloud based file servers, HR applications, or customer support ticketing applications. The targeted employees may be first contacted by either spoofed email or a spoofed phone call, even to personal devices due to mobile numbers being readily accessible through various social media platforms, professional or otherwise. They are subsequently socially engineered into installing remote access software onto their work machines. Please note the phishing emails are NOT the single click kind. They are email threads that appear to be legitimate work business, and the target is tricked into replying and engaging.

Remote Access [T1219]: Once remote access is installed on the employee’s machine, the attackers will seek to login to business applications that require multi-factor authentication. This usually requires a second wave of social engineering in order to overcome the second factor of authentication.

Defense Evasion [TA0005]

Valid Account [T1078]: In order to successfully login to business applications (with the intent to download sensitive data for exfiltration), the attackers must bypass multi-factor authentication. In the cases we have observed, the threat actor has achieved this in two ways. The employee whose machine was compromised may be socially engineered via a live spoofed phone call into entering multi-factor authentication codes directly during a live session, and thus unwittingly provided access to applications while the attacker was remoted into the employee’s machine. The attackers may also make repeated login attempts in order to create a wave of ‘push notifications’ to the target’s mobile device, in the hope that the target just accepts one, without checking the validity of the login attempt, a tactic known as MFA fatigue. Since the attacker is using the employee’s machine and the employee’s credentials, there are no flags or security alerts triggered. The attacker may also spoof an employee’s phone number and call the target company’s IT support desk to request a password reset or temporary removal of multi-factor authentication from certain applications. The justification may be that the employee has lost their phone and thus could not use their multi-factor authentication application, or receive push notifications. The attackers will have done their reconnaissance and know the names of multiple employees of the help desk in order to head off any suspicion. The end goal is to convince the support team to temporarily deprecate the security controls of authentication of the employee whose machine is under the control of the attacker. When successful, multi-factor authentication is overcome, and access to critical business applications / data is achieved by the attacker.

Exfiltration [TA0010]

Exfiltration over Web Service [T1567]: In both cases, CRM applications, support ticketing applications, HR applications, and file server applications were searched and parsed, often with reporting functions utilized to create mass outputs from the applications. The velocity and specificity of the report generation demonstrates high level subject matter expertise with multiple common enterprise SaaS applications. The downloads are first saved locally, and then uploaded to common cloud storage services under the control of the threat actor.

Mitigation

User Training [M1017]: While security awareness training is important for all employees, it is especially important for the IT support helpdesk. Any inbound phone call or ticket that requests a password reset / deprecation / bypass should go through extra validation for legitimacy. IT support team’s should ALWAYS drop the initial inbound call (which was spoofed in multiple cases to appear legitimate), and call the employee back on the phone number listed on an internal directory. Additionally any employee soliciting a password reset or changes to multi-factor authentication should be required to submit a selfie photo of them holding both their government issued ID and a piece of paper stating the request to temporarily suspend multi-factor authentication.

While the above mitigation may seem easy, we recognize the challenges that large enterprises may have in implementing such a procedural change, especially if IT support is offshored. In several of the cases we studied, it was clear that the IT support team’s incentives (speed to resolution) abetted the social engineering. This is not an easy problem to solve, but we commend the enterprises that have mitigated the risks. These fixes meant increased costs and a mild deprecation to the employee stakeholder experience, for the sake of security.

The ‘scattered’ threat actor groups’ rare use of encryption for impact led them to test a new extortion tactic as well. The tactic involves persistence that is extremely deep and time consuming to cleanse. Once achieved, the threat actor then dangles the offer of “pay us and we will leave… Don’t pay us and we will continue to root around causing chaos.” If you read the prior scenario and scratched your head, you are not alone. Paying the criminal for security is not considered a sound strategy. For executives under immense pressure to staunch business interruption costs, the offer of a quick pain killer can unfortunately be appealing (at least in the absence of competent counsel). This of course violates a first principle of incident response:

What feels slow IS actually the fastest route to recovery.

No impacted company can jump out of these situations quickly. Containment takes time. Restoration takes time. Trying to move too fast often results in making matters worse. This is why companies that routinely practice live incident response tabletops fare substantially better during this critical period of time. It turns out that when you practice your IR response, communications and decision making you get better at it! Practice should also include the process of resetting of administrative/privileged accounts, including service accounts and the Golden Ticket for Active Directory. If you are reading this and think practicing a Golden Ticket reset is too expensive and disruptive, well, just wait till you are forced to do it on NO practice during an active ransomware attack.

The offer from the ‘scattered’ threat actor to peacefully leave the environment in exchange for a ransom can be tempting to a hurried, poorly trained decision maker that is under immense pressure. This temptation must be resisted. In the medium and long term (which can be hard to fathom in the middle of an incident) a victim will be substantially better off taking the necessary time to rid their environment of the threat rather than pay the threat actor to leave. Paying a threat actor to leave an environment sends the following signal:

Not only do we lack the ability to secure ourselves, we are willing to pay threat actors to leave us alone.

When cyber extortion actors receive these signals they are substantially more likely to re-attack and re-extort these victims in the future as they are officially the cheapest possible target. One group we track has re-attacked or re-extorted its victims in 25% of observed cases and we expect this percentage to increase with time. Victims who make these payments may think they are solving a problem, in reality they are opening up a dark sequence of events that range from public communications challenges to re-extortion by the same actor for the same data. The risk is hard to visualize early on, but in our experience the long term liabilities eclipse whatever savings were forecasted as justification for the initial ransom.

Ransom Payment Rates in Q3 2023

The proportion of ransomware victims that opted to pay in Q3 2023 jumped up slightly, from 34% in Q2 to 41% in Q3. We do not believe this is the start of a new upward trend, rather normal swings that will occur in the current range of outcomes we observe.

The proportion of victims that opted to pay when ONLY dealing with data exfiltration (DXF) also jumped up in Q3. Again, we do not see this as the beginning of a new trend even though the rate jumped materially. While out of direct purview, we also expect to see a material increase in class actions lawsuits brought against enterprises that experience data breaches, including data exfiltration and extortion events. As previously noted, we have not seen any precedent that paying a ransom mitigates the risk of a class action lawsuit or the ultimate outcome of the lawsuit. In fact, we anticipate that paying a ransom to attempt suppression of a threat actor’s publication of a data breach will INCREASE the potential liability experienced by defendants (more on this in subsequent blog posts).

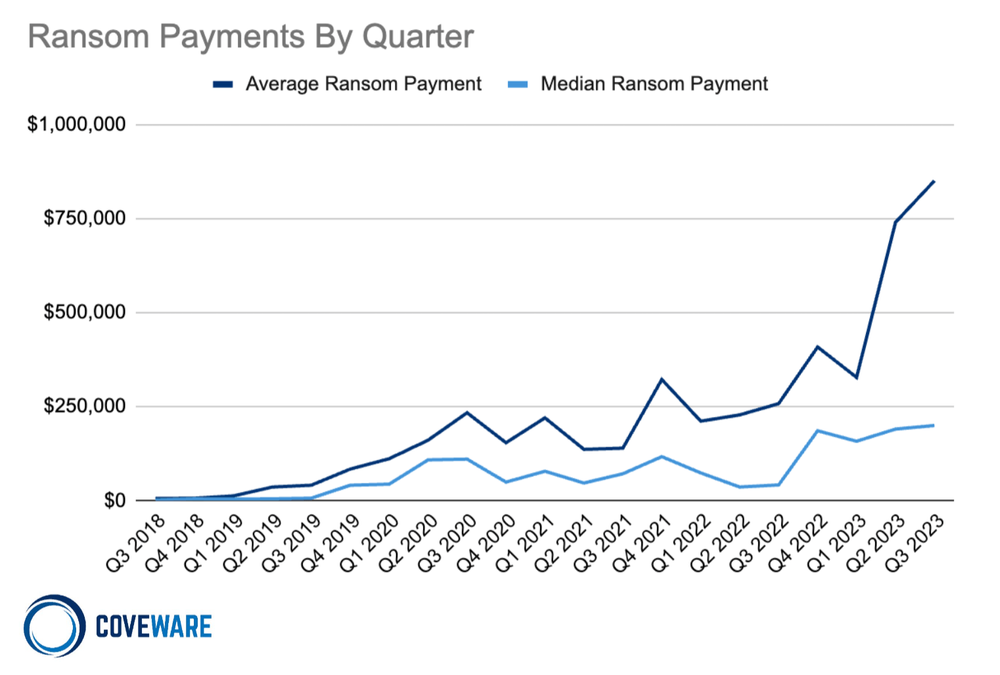

Ransom Payment Amounts in Q3 2023

Average Ransom Payment

$850,700

+15% from Q2 2023

Median Ransom Payment

$200,000

+5% from Q2 2023

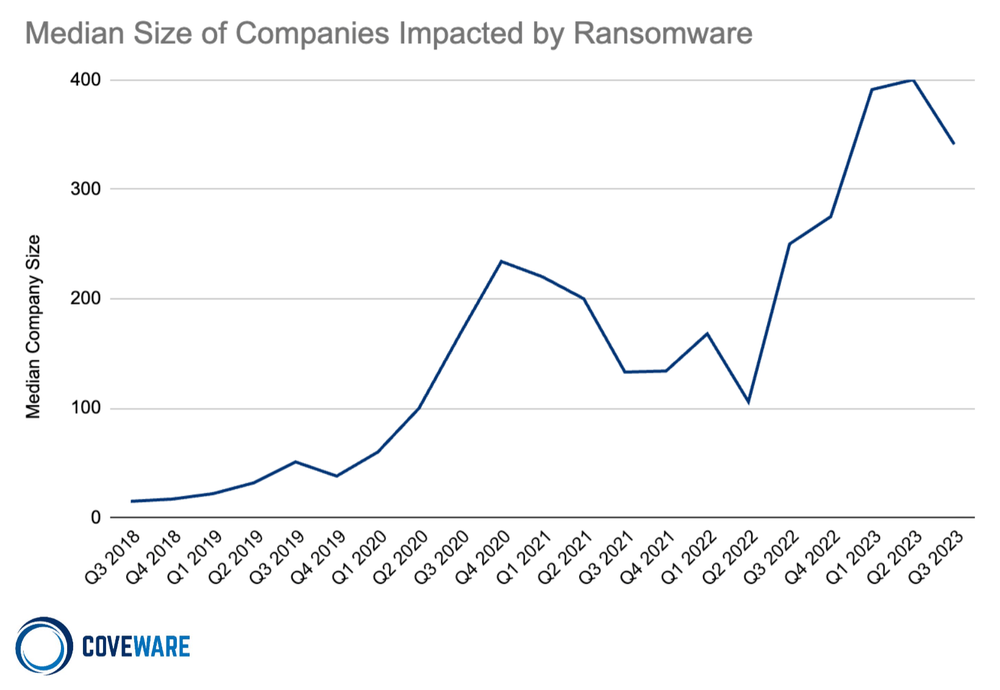

In Q2 2023 the average ransom payment increased to $850,700 (+15% from Q2 2023), while the median ransom payment also ticked up slightly to $200,000 (+5% from Q2 2023). We don’t ascribe any noteworthy observation to this increase beyond a normal rotation of common variants towards ones that tend to impact larger organizations with larger initial demands (even though the median victim size dipped a bit to 341 employees, -15% from Q2 2023).

Most Common Ransomware Variants in Q3 2023

| Rank | Ransomware Type | Market Share % | Change in Ranking from Q2 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akira | 20.1% | +3 |

| 2 | BlackCat | 16.3% | -1 |

| 3 | Rhysida | 7.8% | New in Top Variants |

| 4 | Lockbit 3.0 | 3.9% | -1 |

| 4 | Clop | 3.9% | New in Top Variants |

| 4 | Play Ransomware | 3.9% | New in Top Variants |

Market Share of the Ransomware attacks

Akira ransomware jumped into the top spot of the market share board in Q3 2023 despite the fact that an anti-virus company decided to responsibly disclose the existence of a flaw in the Akira encryption schema. Why did Akira gain more traction attacking companies in Q3 vs. Q2 when a flaw was publicly disclosed and a decryptor published for the public? Ransomware groups actually advertise their encryptors security in order to attract affiliates. With the help of the disclosure, the Akira group was able to patch the vulnerability in a matter of days. This allowed them to harden up their crypto schema and continue impacting victims and attracting new affiliates to carry out an increasing volume of attacks. When vulnerabilities are publicly disclosed to ransomware groups for free, the only winners are the ransomware developers. Once the vulnerability was disclosed, future victims lost that opportunity. We urge all security companies that are tempted by the whims of their product marketing team to publish decryptors and blog posts to first assess the cost / benefit of such an action to the entire community. There are certainly circumstances where publicly releasing a free decryption tool makes sense. An easy example would be a dormant variant that is no longer active, but which impacted a large volume of victims that are still without their data. On the other end of the spectrum, handing active ransomware variants information on their vulnerabilities for free imposes costs on the good guys.

Common Ransomware Attack Vectors and Tactics in Q3 2023

While the most common conclusion to an investigation in Q3 was unknown/undetermined entry vector, the subtext behind this trendline is as follows:

(1) a greater incidence of software vulnerability exploitation that leaves little-to-no forensic footprints that can be used to conclusively identify it as such, AND

(2) a continued reliance of ransomware actors on access brokers who may establish a foothold weeks or months ahead of the actual incident, whose access points cannot be confidently proven due to the expiration of critical forensic artifacts from the time of initial access.

Stolen/leaked VPN credentials continue to be a valuable resource for big game hunters who leverage these persistent, legitimate access points without triggering the same alarms that leveraging a malicious foothold might set off. It is worth noting that a high percentage of VPN credential exploits were against single-factor authentication only VPN appliances.

Phishing remains prevalent despite the disruption of the Qbot botnet. Recent examinations of our data suggest phishing is more likely to be the predecessor to a data-theft-only extortion attack than it is for encryption-focused attacks. We’ve observed that encryption based attacks are more associated with exploited/misconfigured remote access points and software vulnerability exploitation – entry points that can be scraped/stolen/auctioned in bulk. Phishing skews towards attacks that are decidedly more targeted, particularly for large enterprises who are less likely to be plagued by the low hanging fruit of an unpatched VPN appliance or open RDP port. It is not a coincidence that the majority of large enterprises we assist suffer from data-theft-only incidents.

Exfiltration [TA0010]: Exfiltration consists of techniques that threat actors may use to steal data from a network. Once data is internally staged, threat actors often package it to avoid detection while exfiltrating it from the bounds of a network. This can include compression and encryption. Techniques for getting data out of a target network typically include transferring stolen data over threat actor command and control channels. Common exfiltration tools used by threat actors include: Megasync, Rclone, Filezilla, Windows Secure Copy (WinSCP), Cloud User Agents (DropBox, OneDrive). Some actors have favored tools. For instance, Akira prefers WinSCP while BlackCat and the Scattered Spider groups prefer Filezilla.

-

Exfiltration over Web Service [T1567] is the most common sub-tactic, which covers use of a variety of third party tools such as megasync, rclone, Filezilla or Windows Secure Copy.

Impact [TA0040]: Impact consists of techniques used by adversaries to disrupt the availability or compromise the integrity of the business and operational processes. Techniques used for impact can include destroying or tampering with data. In some cases, business processes can look fine, but may have been altered to benefit the adversaries’ goals. These techniques might be used by adversaries to follow through on their end goal or to provide cover for a confidentiality breach. This TTP also includes tampering with credentials to deny access to virtual environments like ESXi. This is a very common tactic used by ransomware groups Akira, NoEscape and Rhysida.

-

Data Encrypted for Impact [T1486]: Encryption of files is the most common form of impact observed. This may include forensics logs and artifacts as well that may inhibit an investigation.

-

Data Destruction [T1485]: Most of the time, data destruction is aimed at the destruction of forensic artifacts via the use of SDelete or CCleaner. Unfortunately, sometimes ransomware actors destroy production data stores (sometimes malicious, sometimes by accident).

Lateral Movement [TA0008]: Lateral Movement by threat actors consists of techniques used to enter and control remote systems on a network. Successful ransomware attacks require exploring the network to find key assets such as domain controllers, file share servers, databases, and continuity assets that are not properly segmented. Reaching these assets often involves pivoting through multiple systems and accounts to gain access. Adversaries might install their own remote access tools to accomplish Lateral Movement or use legitimate credentials with native network and operating system tools, which may be stealthier and harder to track. Favored tactics involve the exploitation of SMB/Windows Admin Shares, internal RDP, and RMM tools such as AnyDesk and ScreenConnect, though these remote access tools are not as popular for Lateral Movement as other purposes.The two most observed forms of lateral movement are:

-

Remote Services [T1021 and T1210], which is primarily the use of VNC (like TightVNC) to allow remote access or SMB/Windows Admin Shares. Admin Shares are an easy way to share/access tools and malware. These are hidden from users and are only accessible to Administrators. Threat actors using Cobalt Strike almost always place it in an Admin share. Usage of internal RDP remains one of the fastest and most efficient methods for lateral movement if a threat actor has the proper credentials.

-

Lateral Tool transfer [T1570]: Primarily correlates to the use of PSexec, which is a legitimate windows administrative tool. Threat actors leverage this tool to move laterally or to mass deploy malware across multiple machines.

Command and Control [TA0011]: Command and Control consists of techniques that adversaries may use to communicate with systems under their control within a victim network. Threat Actors (TAs) commonly attempt to mimic normal, expected traffic to avoid detection. TA’s will use legitimate software, leveraging trusted domains and signed executables, to maintain an interactive session on victim systems. When compared to post-exploitation channels that heavily rely on terminals, such as Cobalt Strike or Metasploit, the graphical user interface provided by RMMs are more user friendly. With the popularity of SaaS (Software as a Service) models, many RMMs are further offered as cloud-based services and by having command & control channels rely on legitimate cloud services, adversaries make attribution and disruption more complex.

Common tools they use are AnyDesk, TeamViewer, LogMeIn and TightVNC. ScreenConnect has been used heavily in Q3, more so than any other RMM. ScreenConnect has a ‘backstage mode’ feature, which allows for complete access to the Windows terminal and PowerShell without the logged-on user being aware which makes it a particularly effective tool. There are many ways an adversary can establish command and control with various levels of stealth depending on the victim’s network structure and defenses:

-

Remote Access Software [T1219]: Ransomware threat actors will use legitimate software to maintain an interactive session on victim systems. Common tools observed in Q3 were ScreenConnect, AnyDesk, TeamViewer, LogMeIn and TightVNC.

-

Proxy: Multi-hop [T1090] tactics are used to direct network traffic to an intermediary server to avoid direct connections to threat actor command and control infrastructure. A common tool observed for this purpose is SystemBC.

Defense Evasion [TA0005]: Defense Evasion consists of techniques that adversaries use to avoid detection throughout their compromise. Techniques used for defense evasion include uninstalling/disabling security software or obfuscating/encrypting data and scripts. Adversaries also leverage and abuse trusted processes to hide and masquerade their malware. Other tactics’ techniques are cross-listed here when those techniques include the added benefit of subverting defenses.

-

Indicator Removal on Host – Clear Windows Event Logs [T1070]: Threat actors regularly clear Windows event logs to avoid possible detection. The two most common event logs cleared by threat actors are the Windows Security and System logs.

-

Impair Defenses [T1562]: Threat actors will leverage Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD) attacks, where the attacker drops known, legitimate drivers signed with valid certificates and capable of running with kernel privileges. However, these drivers have vulnerabilities that grant attackers the ability to execute attacker-provided code in kernel context. This puts the attackers in a privileged position, enabling them to circumvent the limitations imposed by the operating system on user processes to disable security solutions and take over the system. We observed this exploited by Akira using the Terminator.sys BYOVD attack.

-

Process Injection [T1055]: Threat actors may inject code into existing processes, such as rundll32.exe or svchost.exe, in order to evade process-based defenses as well as possibly elevate privileges. Execution via process injection may also evade detection from security products since the execution is masked under a legitimate process.

-

Modify Registry [T1112]: Adversaries may modify the Registry on a machine to stop services and processes, deactivate security configurations, and hide scheduled tasks and other mechanisms used to establish persistence.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Blog | Latest Ransomware News and Trends | Coveware authored by Bill Siegel. Read the original post at: https://www.coveware.com/blog/2023/10/27/scattered-ransomware-attribution-blurs-focus-on-ir-fundamentals

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh