2023-10-30 22:0:0 Author: securityboulevard.com(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

Cybersecurity has become one of the most pressing threats that an organization can face, where poor cybersecurity can lead to operational disruptions, regulatory enforcement, lost sales, a tarnished corporate reputation, and much other trouble.

Management teams know this, of course, and the CISO’s primary job is to build an effective cybersecurity risk management program that can avoid all those missteps. One proven strategy to build such a program is to use a cybersecurity framework — and the best, most trusted source of such frameworks is NIST, the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

That said, NIST cybersecurity frameworks can be a complicated experience for first-time users. This article will walk IT security professionals through the basics of NIST and NIST compliance, its three most popular cybersecurity frameworks, and how a CISO can get started implementing a framework in their own organization.

What is NIST, anyway?

NIST is the National Institute of Standards and Technology, originally established by Congress in 1901 to adopt standard units of measurement (right down to how much liquid should go into a gallon and how long 12 inches should be) and to develop equipment that would weigh and measure physical goods accurately.

Over the years, NIST has expanded to address all manner of business needs, such as better weather balloons in the 1930s and more accurate sensors to measure electricity passing through superconductive metals in the 1990s. Today, NIST exists as a division within the U.S. Commerce Department, still working to assist businesses with more accurate measurements and standards in a wide range of industries.

NIST has also played an important role developing standards for cybersecurity. The three most important frameworks NIST has established are the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF), NIST 800-53, and NIST 800-171. We will explore each one in further detail below.

Who should use NIST frameworks?

NIST frameworks are freely available to any organization that wants to use one. That said, some frameworks are more appropriate than others for certain types of organizations.

For example, NIST 800-53 is a framework intended to help U.S. government agencies and federal government contractors comply with the privacy standards established in the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA). Any organization could follow NIST 800-53 if it wants, but only federal government contractors need to follow 800-53. On the other hand, NIST CSF is a more generalized framework specifically designed to be used (on a voluntary basis) by any organization at all.

Within an organization, NIST frameworks are best used by the CISO and their IT security team, although privacy, internal audit, and GRC functions can use them as well. The frameworks are largely technical documents, with narrative discussions about the frameworks’ overall objectives followed by lists of “control families” that document the specific security controls each framework includes.

Ultimately, however, the correct answer to “Who should use NIST frameworks?” is any organization that wants to take a disciplined, rigorous approach to managing cybersecurity risk. NIST frameworks bring structure to an otherwise enormously complicated challenge.

What should I know about NIST CSF?

NIST CSF was originally published in 2014, in what is now known as Version 1.0 of the framework. A Version 1.1 was adopted in 2018, and is still the active CSF version used today. NIST did release a draft Version 2.0 to the public in August 2023, although a final Version 2.0 is not expected until sometime in 2024 (if you’re curious about the potential changes to NIST CSF, we’ve outlined them all in this eBook, available for free!). For our purposes here, we will refer to the Version 1.1 framework unless otherwise noted.

The CSF is not a checklist that organizations can use to “solve” cybersecurity risks. Rather, the CSF defines a set of outcomes that your cybersecurity program should be able to achieve. It then provides a list of security practices and controls that your organization can implement, depending upon your specific needs.

The NIST CSF Framework Core

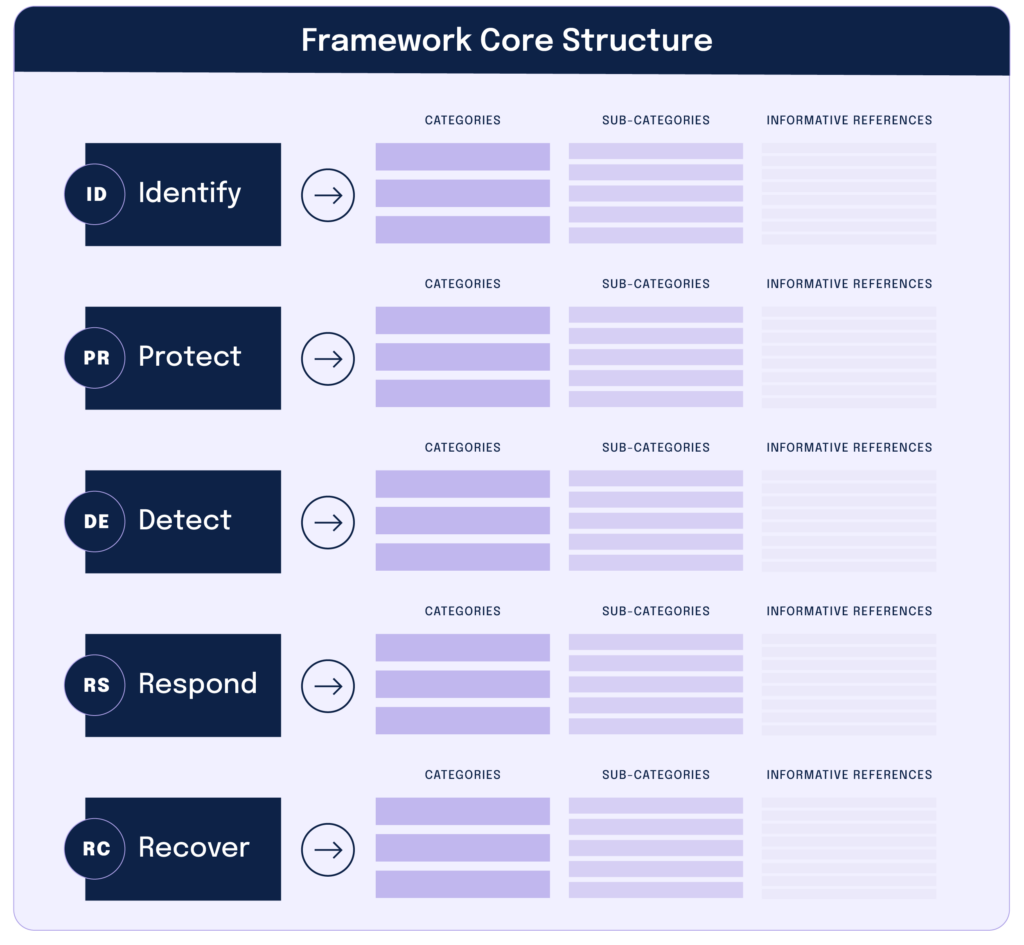

The heart of NIST CSF is the Framework Core: a matrix that identifies the five functions that a cybersecurity program should be able to carry out, with each function then supported by three more specific levels of control known as categories, subcategories, and informative references. Figure 1, below, is the basic structure of the Framework Core.

The elements of the Framework Core work together as follows:

1. Functions

Functions organize basic cybersecurity activities at their highest level. The five functions are identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover.

2. Categories

Categories subdivide each function into groups of cybersecurity outcomes at a more granular level. Examples of categories include “Asset Management,” “Identity Management and Access Control,” and “Detection Processes.”

3. Subcategories

Subcategories subdivide each category into even more precise outcomes, such as “External information systems are cataloged” and “Data at-rest is protected.”

4. Informative references

Informative references are specific sections of standards or guidelines that illustrate a method to achieve the outcomes for each sub-category. The standards cited here include COBIT, ISO, CIS CSC, and even other NIST security standards.

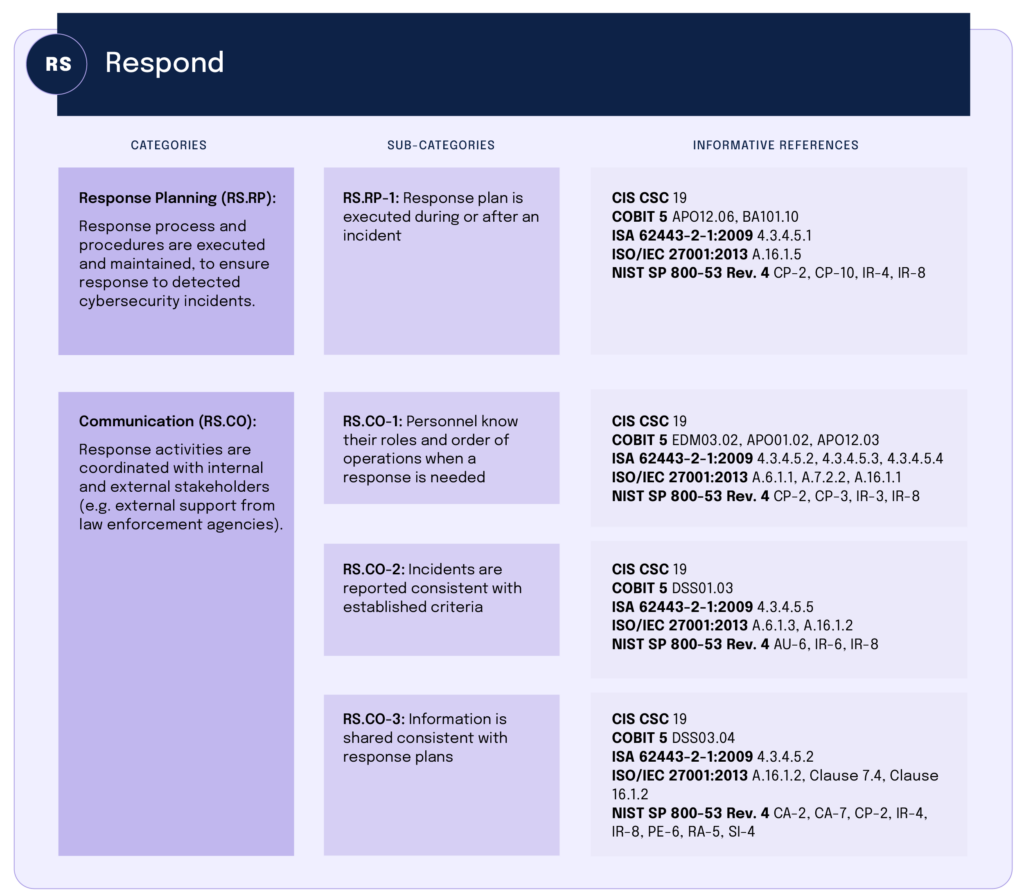

The image below is from Appendix A of the CSF. It shows how one might use the CSF to understand the categories, subcategories, and informative references included in the CSF’s Respond function.

Appendix A lists the categories, subcategories, and informative references for all five of Framework Core’s five functions. Essentially, an IT security team can go through the entire appendix, confirming which categories and subcategories exist within your cybersecurity program, and whether the controls for each of those items match the expectations stated in the informative references.

The NIST CSF Framework Tiers

In addition to the Framework Core, the CSF also has Framework Tiers to help an organization understand the maturity of its cybersecurity program and what might be necessary to push your program to a higher level of performance.

The Framework Tiers are organized on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest):

Tier 1: Partial

Cybersecurity risk management practices are not formalized, and there is only limited awareness of cybersecurity risk at the enterprise level.

Tier 2: Risk Informed

Management approves risk management practices, but those practices might not exist as part of an enterprise-wide policy. Cybersecurity information is shared within the organization only on an informal basis.

Tier 3: Repeatable

Management approves of the organization’s cybersecurity practices , and they exist as a formal, enterprise-wide policy; the organization updates those practices regularly as a result of risk assessments and the evolving business, technology, and threat landscapes.

Tier 4: Adaptable

Organizations understand the relationship between cybersecurity risk and organizational objectives and consider it when making decisions. The organization can adapt to a changing threat and technology landscape and responds swiftly to evolving, sophisticated threats.

What should I know about NIST SP 800-53?

NIST Special Publication 800-53 (more commonly known as “NIST 800-53”) is a more exacting framework that specifically deals with information security and privacy. The current version of NIST 800-53 is Revision 5, adopted in 2020.

NIST 800-53 governs how organizations should protect confidential information. This can include personal data, financial data, terms of a federal government contract, or other information that is sensitive and needs protection. Implementing the controls defined in NIST 800-53 brings an organization into compliance with the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) and the Federal Information Processing Standard Publication 200 (FIPS 200).

Any organization can use NIST 800-53 to improve its cybersecurity program, but federal agencies and their government contractors are required to adhere to the 800-53 framework as part of their compliance with FISMA and FIPS 200.

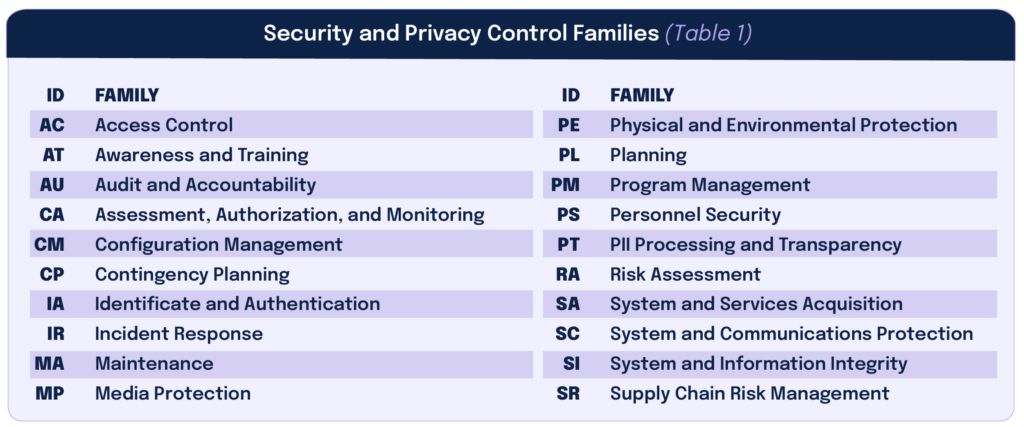

NIST 800-53 contains more than 1,000 individual security controls. Those controls are grouped into 20 control families, as shown in the image below.

Organizations don’t need to assure compliance with every single 800-53 control. Rather, an organization should consider which controls it needs to have based on its federal government contract and the organization’s unique cybersecurity risks, and then implement that smaller subset of controls as necessary.

What should I know about NIST SP 800-171?

NIST Special Publication 800-171 is another cybersecurity framework that applies specifically to organizations working on contracts with the U.S. Department of Defense. The current version of NIST 800-171 is Revision 2, last updated in 2021.

NIST 800-171 spells out how to handle “controlled, unclassified information” (CUI) that exists in defense contracts. Such information would include all the personal and financial data mentioned for NIST 800-53, as well as other sensitive information about defense contracts that falls short of being classified information. Implementing the controls in 800-171 allows an organization to comply with the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), which is the threshold organizations must meet if they want to bid on U.S. defense contracts.

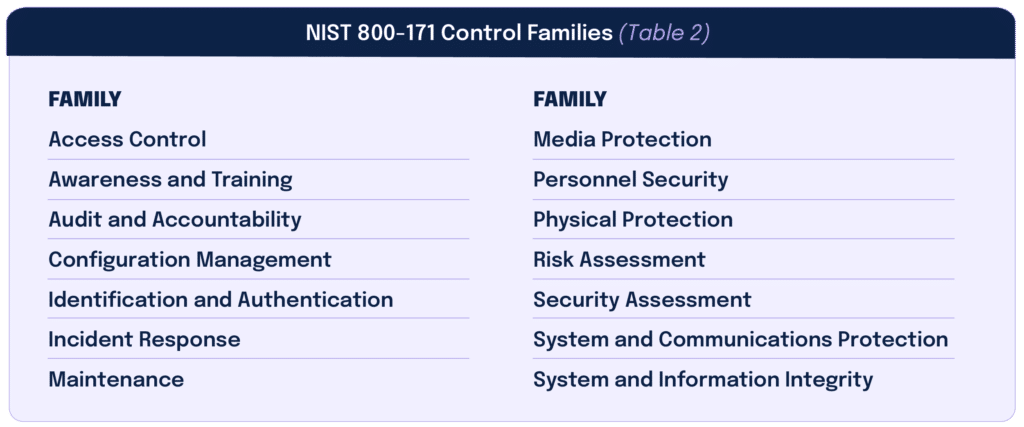

Somewhat surprisingly, NIST 800-171 is actually shorter and simpler than 800-53. It contains only 110 controls, spread across 14 families. See the table below.

Again, organizations won’t necessarily need to assure compliance with every single 800-171 control. They only need to implement those controls that are necessary based on each organization’s own unique risks and the terms of the defense contract the organization is bidding upon.

How do I begin implementing a NIST framework?

Implementing any NIST framework is no easy task. NIST offers many resources to help cybersecurity teams, so it’s always wise to visit the website of the exact framework you want to implement and the review materials posted. GRC software vendors can also assist with templates and other tools to help on your implementation journey.

For the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, NIST has published a Quick Start Guide that walks through all five functions of the Framework Core, with specific suggestions for how to address the primary goals of each function. NIST has also published sample “framework profiles” that demonstrate how the CSF might work in specific organizations, including profiles for manufacturing businesses, electric vehicle charging networks, election infrastructure, a payroll business, and many more.

Newcomers to NIST cybersecurity frameworks can start by reviewing the Quick Start Guide and any framework profiles that fit your own organization. Then, work with your audit or cybersecurity advisers to develop specific policies, procedures, data security controls, and other controls that meet your needs.

Getting started with NIST 800-53 and 800-171 is more complicated. NIST has listed nine steps an organization should undertake to assure compliance with FISMA, which are:

- Categorize the information to be protected

- Select minimum base controls

- Refine controls using a risk-assessment procedures

- Document the controls in the system security plan

- Implement security controls in the appropriate information systems

- Assess the effectiveness of the security controls once they have been implemented

- Determine the agency-level risk to the mission or business case

- Authorize the information system for processing

- Continually monitor the security controls

Since NIST 800-53 is the basis of FISMA compliance, and 800-171 tackles the same sort of information protection issues, the nine steps above are a good, fundamental blueprint for compliance with either framework.

Still, cybersecurity teams should always understand that compliance with NIST frameworks can be enormously complicated. Many large organizations may need to comply with several NIST frameworks or find that their compliance with other frameworks — for example, the PCI DSS framework for credit card data, or the ISO 27001 standard for information systems management — overlaps with their NIST compliance obligations.

To avoid confusion, wasted time, or duplicative controls, companies should use a dedicated tool that maps out the requirements of your various cybersecurity frameworks to understand where those requirements do or don’t overlap. Ideally, the tool can also then map your existing controls to the requirements as well so you can see where one control might fulfill the requirements of several frameworks — or where you are missing a control and need to create one.

One final point for NIST 800-53 and 800-171 is that compliance with both frameworks requires an audit. So as you select and implement cybersecurity controls, you must also consider the documentation and other evidence necessary to support control assessments during that audit. You should then store the documentation in a single data repository to avoid any confusion about which controls have already been implemented or what work remains to be done.

How Hyperproof can help

The NIST frameworks can be an invaluable source of guidance to help any organization navigate today’s complex cybersecurity and regulatory compliance landscapes. CISOs need to think carefully about which frameworks make the most sense for them and then bring together the right people, tools, and processes to assure that you execute your NIST compliance project as smoothly as possible.

On the other side of that journey, however, an organization that has implemented NIST frameworks has better security and stronger compliance and generates more trust with its customers, investors, and other stakeholders. The journey is worth the effort.

Looking for support in implementing a NIST framework? See why AppLovin chose Hyperproof to manage risks and track controls, creating a single source of truth mapped across multiple frameworks like NIST CSF and ISO 27001.

The post A Complete Guide to NIST Compliance: Navigating the Cybersecurity Framework, NIST 800-53, and NIST 800-171 appeared first on Hyperproof.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Hyperproof authored by Matt Kelly. Read the original post at: https://hyperproof.io/resource/a-complete-guide-to-nist-compliance/

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh