read file error: read notes: is a directory 2023-9-29 19:0:42 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:20 收藏

Executive Summary

The CL0P ransomware group recently began using torrents to distribute victim data after a successful campaign stealing data from thousands of companies. We’ll cover the reason for this shift in methodology and what this means for visibility to the outside world.

CL0P has been one of the ransomware groups most actively posting data about their victims on leak sites tracked by Unit 42 (second only to LockBit in 2023). Unit 42 consultants have recently observed CL0P in about 10 incident response cases.

CL0P’s torrent seed infrastructure provides a unique opportunity for us to peer into the direct workings of a notorious ransomware group and provide insights into their trade craft. By analyzing the existing torrent seed infrastructure that hosts the stolen data, we can get a better view into what the implications of this change are.

To protect the victims of this attack, and to have a little fun with one of our favorite fandoms, we’ve swapped the organizations’ names for those of Pokémon.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection from CL0P ransomware and other malware through Cortex XDR. Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from and mitigations for the recent MOVEit vulnerabilities in the following ways:

- Cortex XDR and XSIAM agents help protect against post-exploitation activities associated with the MOVEit vulnerabilities using Behavioral Threat Protection, Anti-Webshell Protection and multiple additional security modules.

- Cortex Xpanse customers can identify external facing instances of the application through the “MOVEit Transfer” attack surface rule.

- Organizations can engage the Unit 42 Incident Response team for specific assistance with this threat and others.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Ransomware, CL0P, Linux |

Table of Contents

History of CL0P and the MOVEit Transfer Vulnerability

The Torrents

The Plan

The Approach

Mapping Peers and Pokémon

Gotta Catch Em All!

Seed Group 1

Seed Group 2

Seed Group 3

Conclusion

Protections and Mitigations

Cortex XDR and XSIAM

Cortex Xpanse

History of CL0P and the MOVEit Transfer Vulnerability

At the end of May 2023, a software product by Progress called MOVEit was the target of a zero-day vulnerability leveraged by the CL0P ransomware group.

CL0P has taken credit for exploiting the MOVEit transfer vulnerability. The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA) has estimated this group has more than 3,000 U.S.-based organizations and 8,000 global organizations victims.

This is old news, but what happened next was quite interesting. To give a little background, CL0P emerged in early 2019 and quickly became notorious for employing extortion tactics against victims to increase the pressure to pay the ransom. They steal the data and release snippets of it. The idea here is that the victim would rather pay than risk having their data exposed globally, which could be more damaging than any traditional ransomware activity.

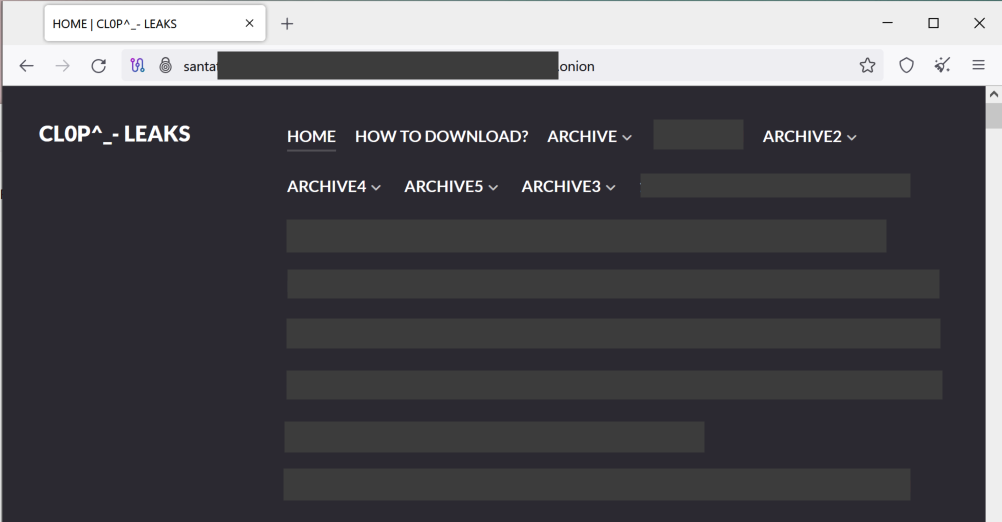

This data is then posted on a “leak site,” as shown in Figure 1, which is served via the Onion router (Tor) network. Doing so allows CL0P to remain relatively anonymous behind this service. (Note that not all the suspected victims of mass exploitation are listed on the leak site.)

If you’ve ever done anything with the Tor browser in the past, you likely noticed almost immediately just how slow everything was. You’re effectively sacrificing latency and throughput for anonymity. While this has improved significantly in recent years, attempting to download data from the leak sites can still prove to be a challenge simply because of the transfer speeds.

But what happens to download speeds when you’ve stolen data from literally thousands of companies? All of a sudden you go from trying to offer up comparatively smaller amounts of data to offering an amount of data that probably forced the individuals behind CL0P to run out and load up on hard drives like they were going out of style.

Threat actors have stolen and leaked terabytes upon terabytes of data already, and a dizzying amount of data is expected to continue to drop. It’s an amount of data that hasn’t been seen before with this type of activity. Unexpectedly, this almost benefits the victims, because it can be impractical to acquire some of the leaks over the Onion network. Why pay a ransom when no one will even be able to download the stolen data?

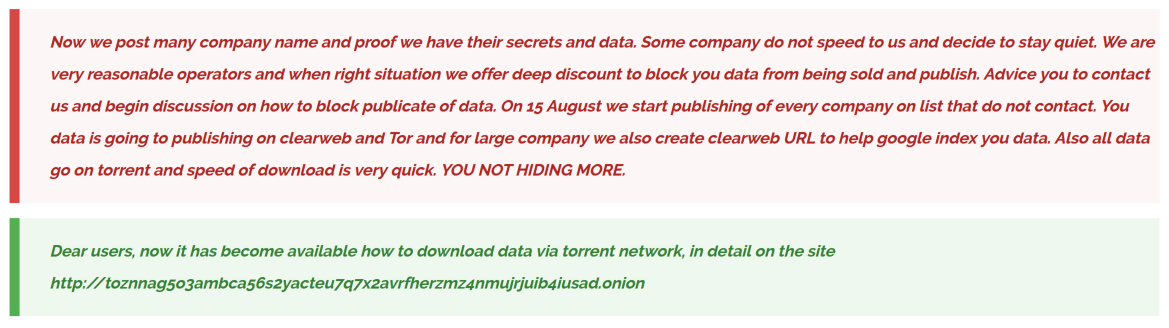

Thus, CL0P changed their tactics to address this new data access problem. They posted on their leak site (as shown in Figure 2) that as of Aug. 15, 2023, they will begin publishing the stolen data through a number of new methods, including torrents. This method leverages peer-to-peer file exchange, significantly speeding up the download process.

To that end, the threat actors made good on their claim and created a new leak site (shown in Figure 3) that had magnet links, which are hyperlinks that include a hash of the file. Most torrent clients could use these links to download the data.

Each day threat actors have steadily released a new set of victims’ data via this method when the victims have refused to pay their extortion amount.

![Image 3 is a screenshot of the CL0P leak site. Some information has been redacted. It gives instructions on how to download leak data via torrenting. Step 1: download and install free utorrent client (if you don't already have it) [link to utorrent download page] or any other torrent client that you prefer. Step two : run utorrent and select file > add a torrent from URL. Utorrent file menu is displayed. Highlighted in red is add torrent from URL. Paste magnet URI to the Add torrent from URL dialog box and click OK button. Screenshot of add torrent from URL popup from utorrent. Please enter the location of the .torrent you want to open. OK button. Cancel button.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/word-image-130278-3-1.png)

Instead of trying to download a 128 GB ZIP file over the Onion network that could take days or even weeks to obtain, people can now download them at much more reasonable speeds. Thus the pressure is back on the victims to pay.

There is a problem with torrents though, which is that the data has to be seeded initially, so that you can bootstrap the download speeds for everyone else. This gives us a unique opportunity to get some insight into CL0P operations by identifying and analyzing the initial seeds for these torrents. This identification process will be the primary focus of this blog.

The Torrents

Before diving into the analysis aspect, it would be helpful to review some concepts of torrenting and how it functions.

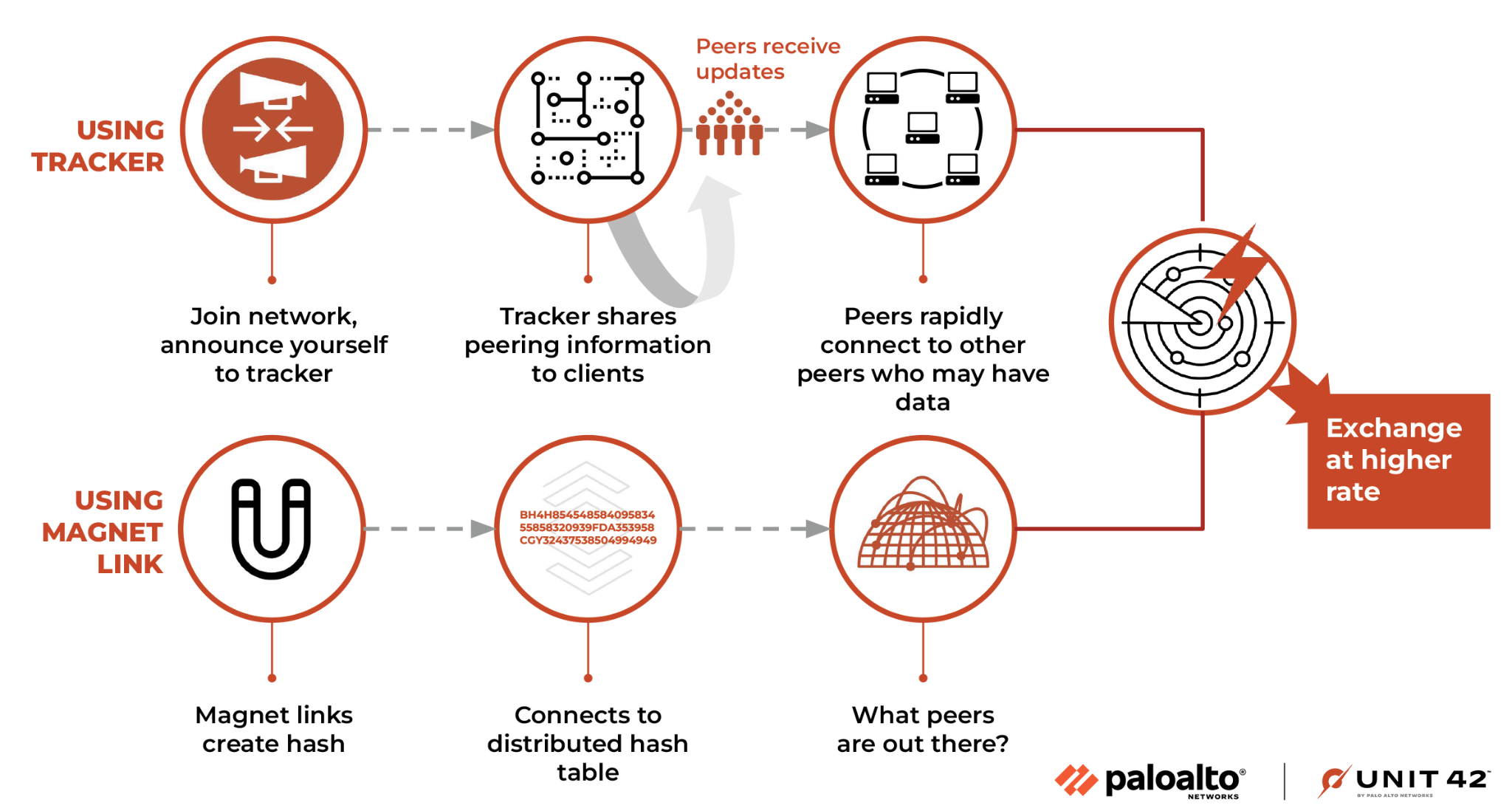

There are two types of “torrents” you should know about. There is the usual torrent file itself, which most people are familiar with, and the magnet links. A torrent file will include a piece of information about a tracker, and when you join the torrent, you will announce yourself to the tracker.

This tracker then will share peering information to the clients, so they can periodically receive updates about other peers who might have pieces of the data they are trying to download. This allows the peers to rapidly connect to multiple other peers and begin exchanging the data at a higher rate.

Trackers are great for normal exchanges, but they may not be the best for operational security because they provide a list of the peers.

Magnet links are similar to a torrent file, but they typically do not have any tracker-related information. Instead, when a client loads a magnet link, it will contain a hash calculated from a number of facets of the file, which is used to uniquely identify the data the torrent represents.

This trackerless torrent works by connecting to one of the distributed hash table (DHT) nodes and effectively asking that node what peers it knows about, so you have someone to begin exchanging information with. This process is shown below in Figure 4.

These peers can then exchange information about other peers they know about, and they can begin building out the web of connections that will eventually speed up the download process.

This decentralized approach is what CL0P has chosen for their data distribution.

The Plan

Of course, this trackability is not news to anyone who has ever used BitTorrent before. Authorities, law firms and others have used this mechanism to track peers connecting to torrents for piracy-related activities for years.

You might remember in the late 1990s when the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) took legal action against Napster. What followed was years of individuals being sued for participating in these peering exchanges because these organizations could identify the IP addresses of the connected peers.

So what makes this any different? The main differentiating factor here is that we’re not dealing with one torrent for one stolen movie, but hundreds of individual torrents. These torrents each require an initial seed for peers to connect to, to begin downloading and exchanging the data. This creates a window of opportunity wherein only one peer will have 100% of the file while the rest of the peers are downloading the pieces of it.

The name of the game with identification is speed, and two factors play into this. First, the speed in which you can join this decentralized swarm. Second, the speed in which you peer with the initial 100% seeder.

Neither of these factors are terribly reliable when dealing with just one torrent. However, it paints a much different picture when you look at things from a 10,000 foot view with all the torrent data combined.

Admittedly, I was a little late to start this research and missed the first days of their announcements before I took an interest in it. This means that I joined the torrents later in their lifecycle and the resulting 100% peers are not as reliable as the original seeders. To counteract this effect, I looked at all the peers across the torrents as the threat actors released them and cross-referenced with the older torrents. This allowed me to see which ones are likely “real” seeders vs. other people who have downloaded the data.

Before moving on, I need to include just one quick caveat here. Many people download these data leaks for various reasons. Sometimes it’s for nefarious reasons such as credential harvesting, IP theft or further exploitation of the victim.

However, there are a number of other entities that download this data with good intentions. They use it to further help the victim or other organizations, or for research. While I cannot infer intent, I can at least compare the behavior of both groups of entities to understand what a “seeder” looks like versus someone downloading it for other reasons.

The Approach

Like I mentioned before, speed is essential. There is a small window of time to join a torrent and with each passing second the likelihood of finding the original seeder diminishes. To address this problem, I need to constantly monitor their leak sites for new announcements and then use the magnet link to begin the peering process.

Once connected to the torrent, I can sit in the swarm and monitor for peers until I find the first one displaying a 100% complete status. At this point, I log the information and remove myself from the swarm.

In an effort to protect the innocent, I have changed all the victim organization names to Pokémon, which also happens to align with the theme of trying to capture and collect all the seeders! Standard legal disclaimer: The listed organizations are not associated with Nintendo – we’re just big fans and enjoy a fun analogy.

When I’m connected to a torrent, this is what the ideal output will look like.

| $ cat pikachu.out | |||||

| Address | Flags | Done | Down | Up | Client |

| 81.19.135.21 | DEHI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Transmission 3.00 | |||||

This output should include the following:

- IP address of the connected peer

- Flags for the peer status

- Percentage complete

- Up/down speeds

- Torrent client

In this case, the flags DEHI mean that:

- I am (D)ownloading from the peer

- Using an (E)ncrypted connection

- I learned of the peer via a D(H)T node as opposed to peer exchange

- The peer is an (I)ncoming connection

All this data is useful for analysis.

In this case, I was connected to a single peer that had 100% completion right after the announcement was made and thus I can reliably assume this is an original seeder. I’ll come back to this later and discuss this particular IP address at length.

These next two are examples of when I was late to the party and did not get enough reliable information to make any determinations with this data alone.

| $ cat squirtle.out | |||||

| Address | Flags | Done | Down | Up | Client |

| 5.62.43[.]184 | D?EHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | µTorrent 3.6.0 |

| 85.12.61[.]195 | TDHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | qBittorrent 4.5.4 |

| 96.241.165[.]117 | TDHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | BitWombat 1.3.0.2 |

| 113.30.151[.]125 | TD?EHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | BitTorrent 7.0.0 |

| 151.20.161[.]85 | DEHI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Transmission 2.93 |

| 178.62.25[.]161 | TDHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | qBittorrent 4.4.1 |

| 183.60.144[.]94 | TDHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | libtorrent (Rasterbar) 2.0.7 |

| 187.170.4[.]251 | DEHI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Transmission 2.93 |

| 192.142.226[.]133 | D?EHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | µTorrent 3.6.0 |

| 195.94.15[.]255 | D?EHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | µTorrent 3.6.0 |

| 223.109.147[.]211 | TDHI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | libtorrent (Rasterbar) 2.0.7 |

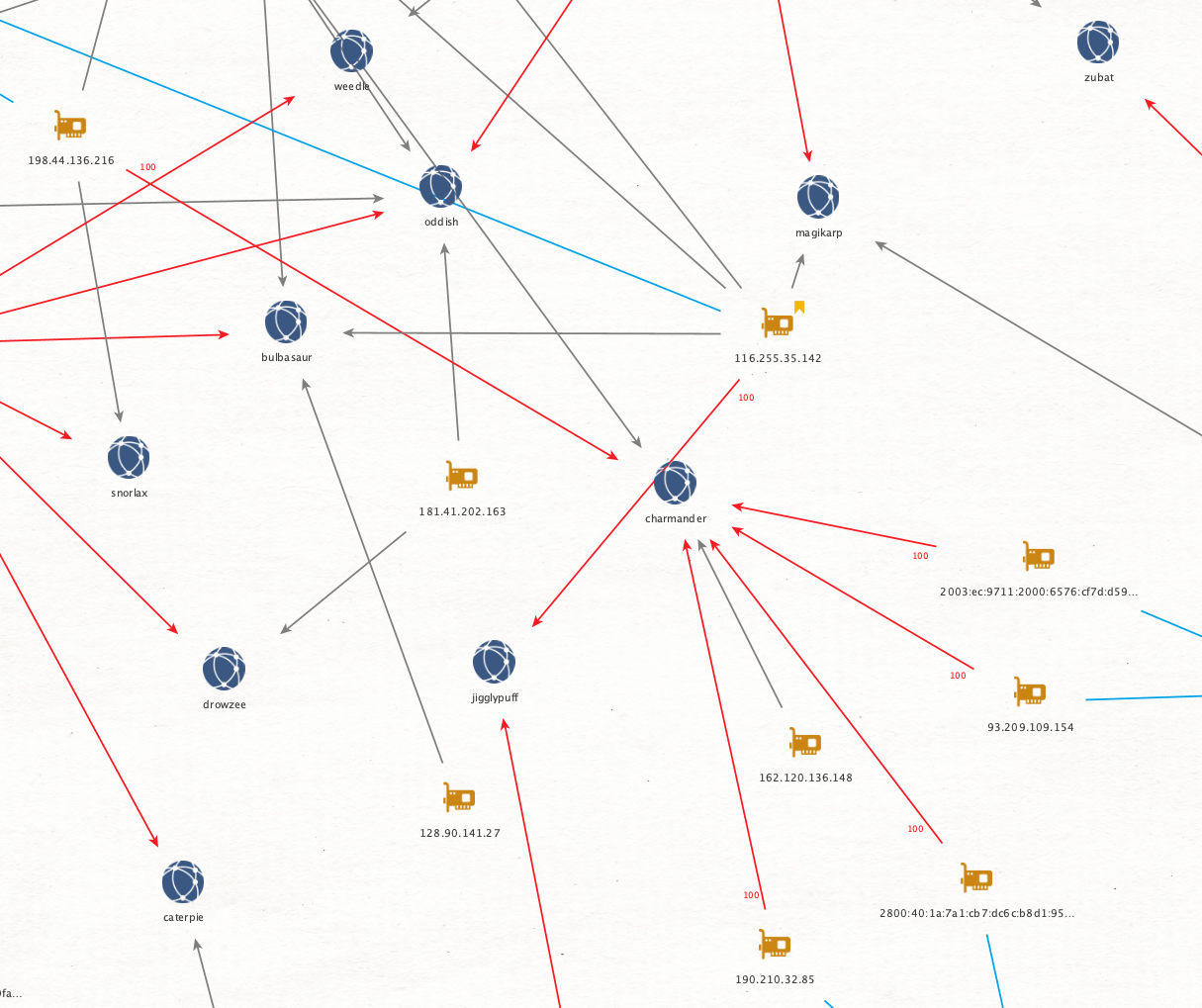

| $ cat charmander.out | |||||

| Address | Flags | Done | Down | Up | Client |

| 2003:ec:9711:2000:6576:cf7d:d597:cb42 | TDEI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Transmission 4.03 |

| 2800:40:1a:7a1:cb7:dc6c:b8d1:9593 | TDEH | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | qBittorrent 4.6.0 |

| 2a01:e0a:aa4:7b30:c87b:ad9b:7a44:2692 | TDEH | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | qBittorrent 4.5.4 |

| 93.209.109[.]154 | DEI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Transmission 4.03 |

| 162.120.136[.]148 | TD?EH | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | µTorrent 3.6.0 |

| 190.210.32[.]85 | DEHI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | qBittorrent 4.6.0 |

| 198.44.136[.]216 | TDEHI | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | qBittorrent 4.5.4 |

In both of these instances, there are multiple peers with 100% completion and so, on the surface, this information is useless. However, it becomes considerably less useless when you begin mapping out all the peers from hundreds of torrents.

Mapping Peers and Pokémon

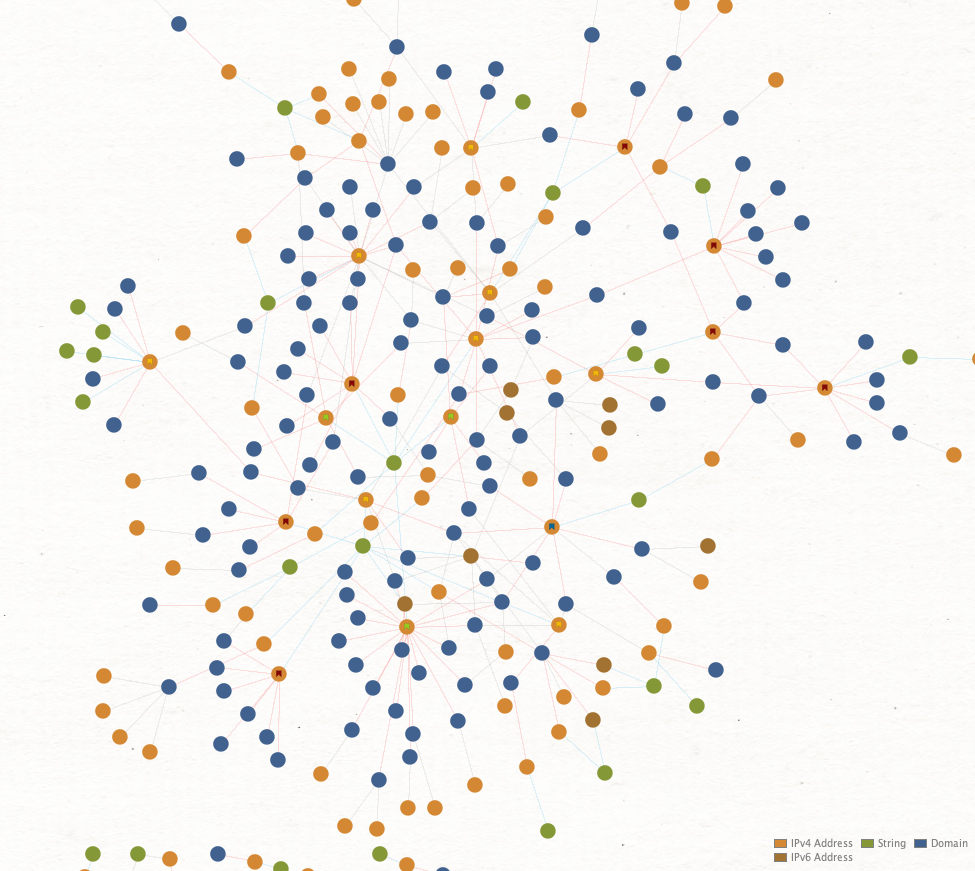

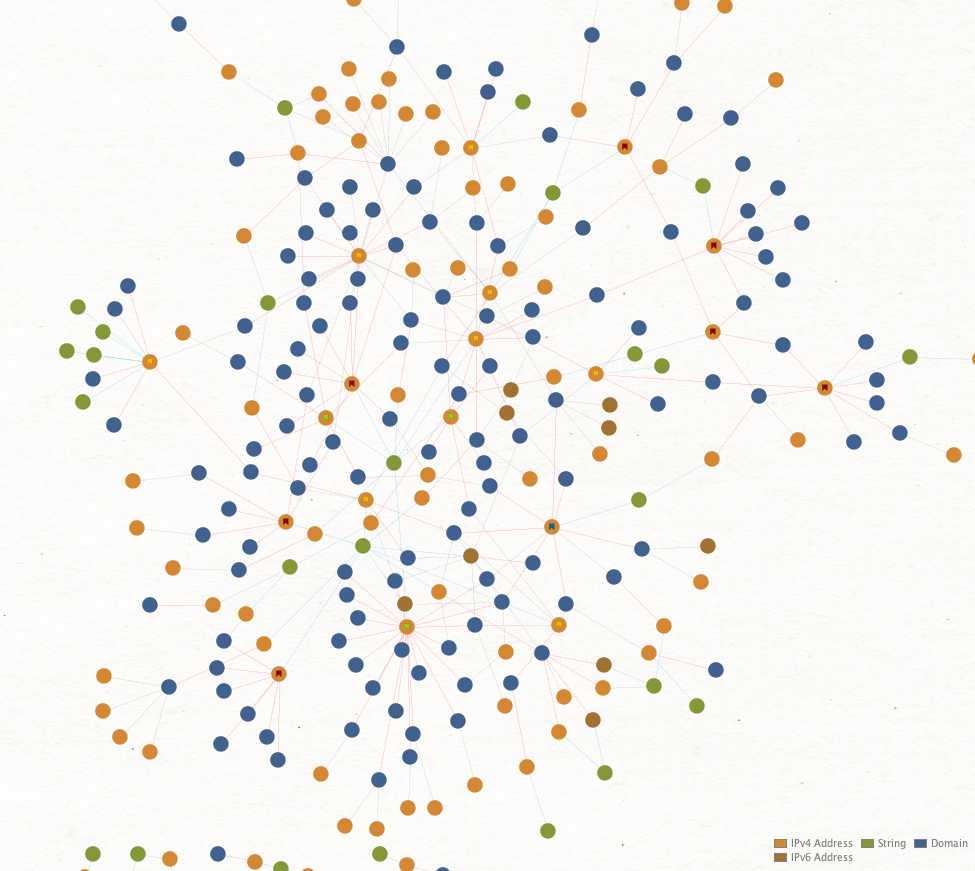

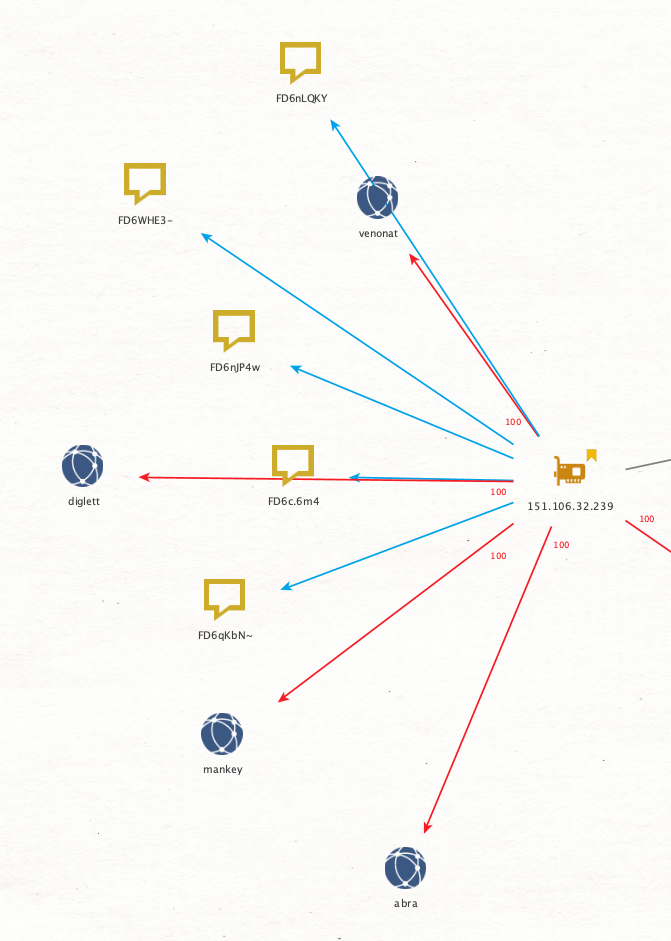

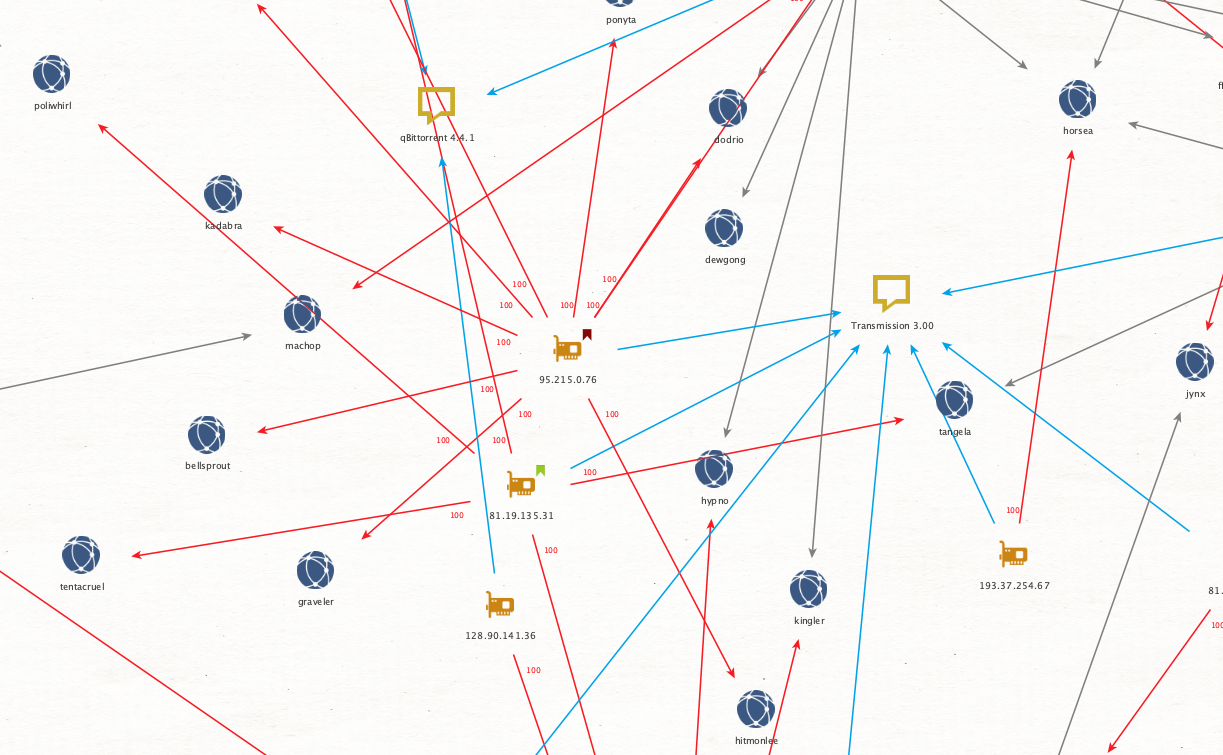

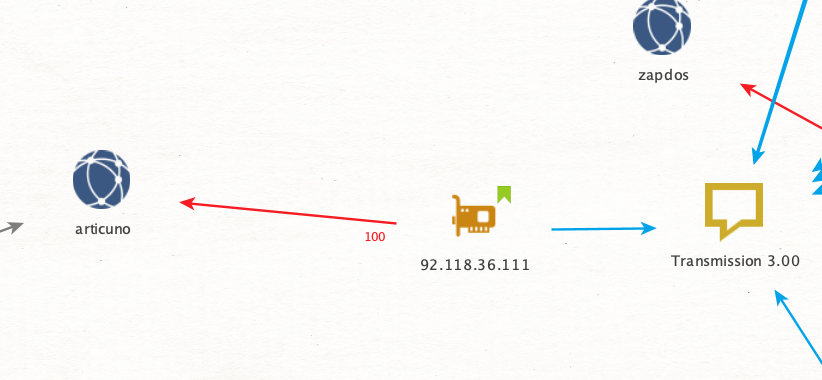

What you end up with after linking some of these data points is a web of connections that we can visualize for better analysis.

Figure 5 focuses on three different data points:

- The address of the peer

- The victim

- The client observed as in use

From there, I connected each node based on the amount of observed data the peer had at the time of logging. Then I color-coded the links as shown in Figure 5, so the 100% links stand out. This allows for quick inspection to identify addresses, which fall into one of three categories:

- A confirmed original seeder

- A potential original seeder

- Nonoriginal seeders

Looking at Charmander again you’ll note two gray lines pointing toward it. These are sub-100% links (I coded all the 100% links red). The blue links connect a peer to their observed client string, seen in Figure 6.

By going through the process of adding each host, when we switch from looking at the victim to the peers, patterns start to appear that draw immediate attention and make me feel like Charlie from Always Sunny in Philadelphia conspiratorially drawing connections!

If a host has all 100% links but a low volume, such as only 2-4, then I consider them a potential seeder. If a host has all 100% links but a high volume, then I consider them just a potential original seeder. Any host who has any sub-100% links, I consider them a nonoriginal seeder.

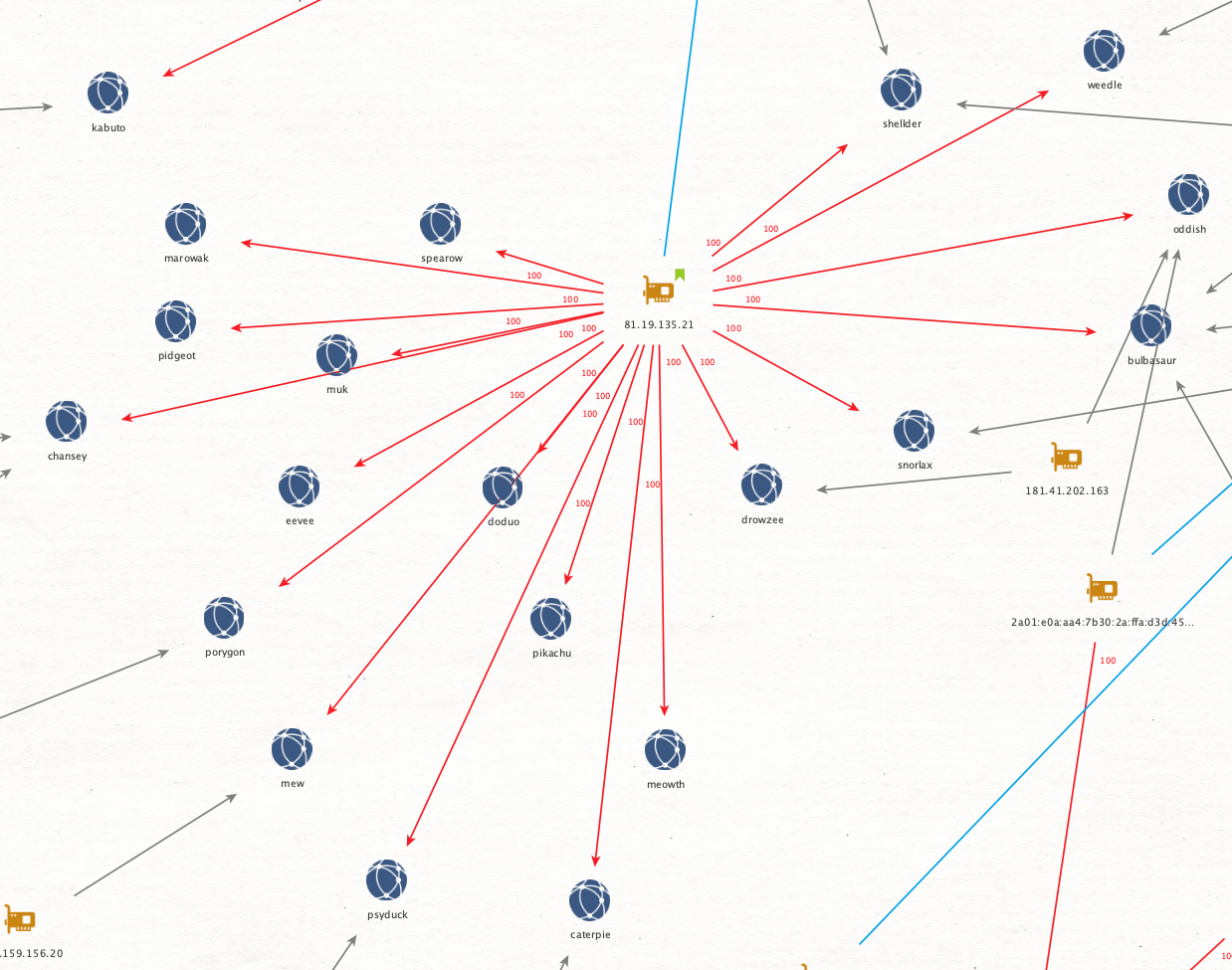

Circling back to the previous IP address 81.19.135[.]21 (shown in Figure 7) we can see what a highly probable original seeder looks like.

A highly probable original seed is characterized not only by having a high volume of 100% seeds, but also by being the only logged peer for a number of victims. Furthermore, patterns start to emerge between the clusters of peers.

For example, the majority of hosts that I believe are original seeders all use the Transmission 3.00 client string, further binding their activity together. Whereas a host with a relatively unique client string that isn’t observed much (like the one in Figure 8) makes me lean more toward them being an entity that is just downloading all the data for other reasons, and that they have completed their downloads.

All this is to say that these data points allow me to then filter and weed out the less interesting peers quickly so that I can focus my attention on the ones that matter.

This individual shown in Figure 9 even changes their client string with every torrent. This adds weight to the supposition that they are not an original seeder, even though they were seeding a lot of the data by the time I peered with them.

By looking at the data and applying the above logic, I’m able to overcome some of the previous issues we discussed, where I hadn’t started collecting data until after they started releasing the torrents.

In total, I was able to identify five hosts that I believe have a high likelihood of being original seeders in this dataset, along with two that will likely become future seeders. This warranted a deeper dive.

Gotta Catch Em All!

Seed Group 1

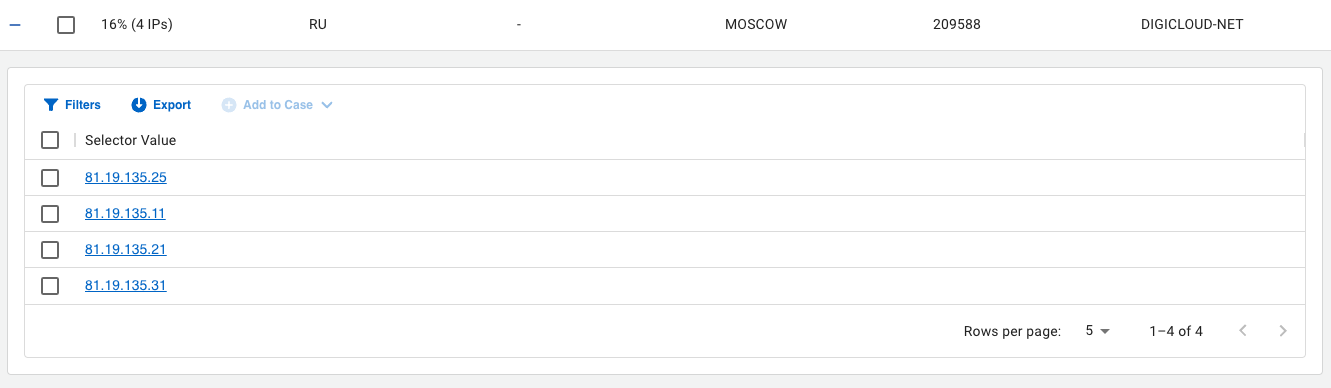

One pattern that stood out almost immediately was that three of the IP addresses are seemingly on the same network.

- 81.19.135[.]21

- 81.19.135[.]25

- 81.19.135[.]31

All three of these IP addresses exist within the same subnet on AS 209588 owned by FlyServers, which is a VPS hosting company. The IPs are geolocated to Moscow, Russia. Each exhibits interesting characteristics that further connect them together making a strong case for them being actor controlled.

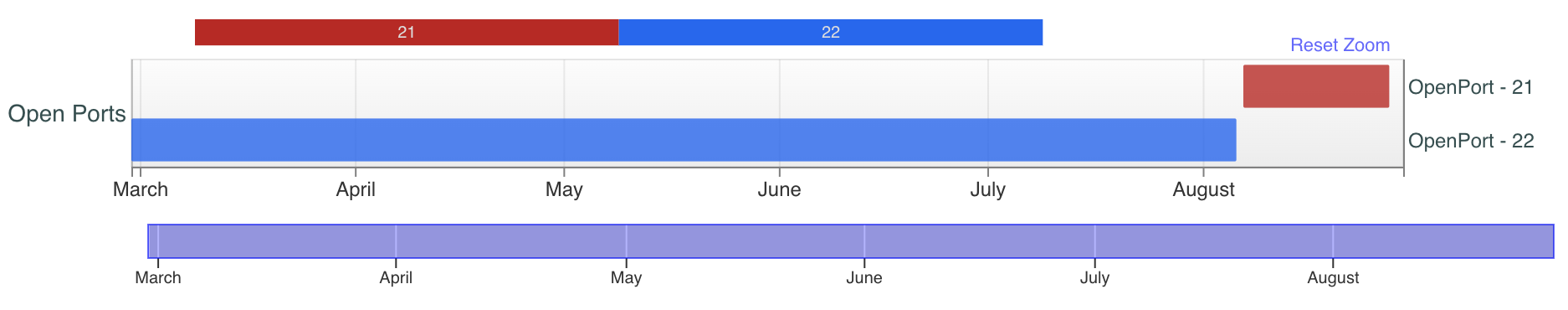

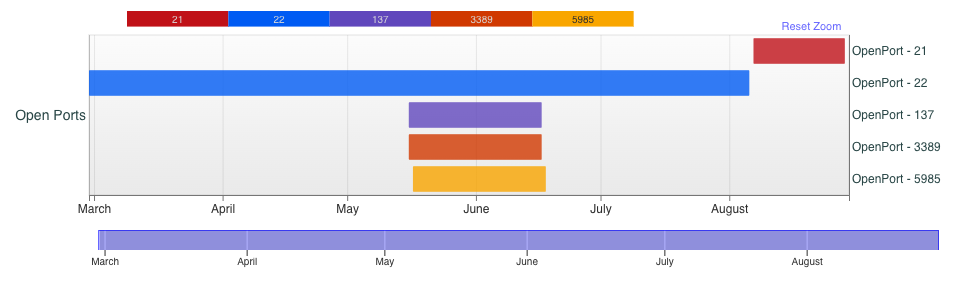

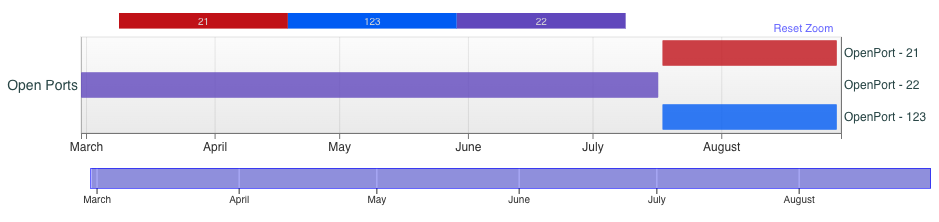

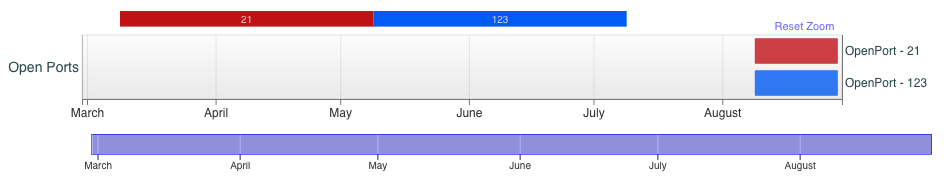

For example, note the pattern shown in Figures 10 and 11, as it relates to SSH availability and FTP availability for the first two IP addresses:

For the IP ending in 21, SSH ports stopped responding on Aug. 6, 2023, and FTP ports started responding on Aug. 7, 2023. For the IP ending in 25, we see SSH stop on Aug. 6, 2023, and FTP open on the same day.

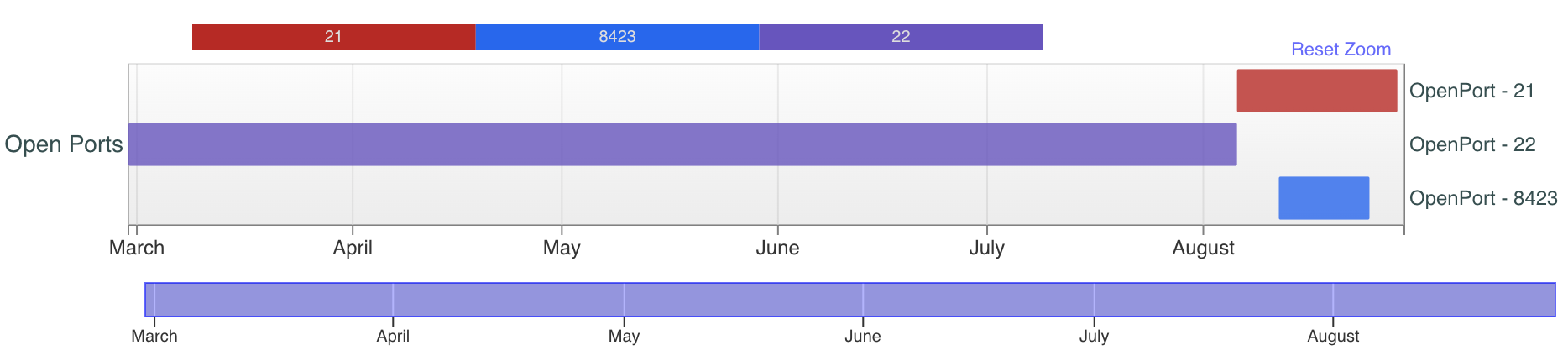

Similarly, for the IP ending in 31 shown in Figure 12, while we did not have visibility of SSH, we can see the FTP also opened up on August 6.

The servers are running vsFTPd 3.0.3 and OpenSSH_8.4p1. The brief visibility on TCP/8423 for the IP ending in 25 reveals it transitioned to running SSH on a nonstandard port.

To confirm the seeding servers were different entities, as opposed to being the same box behind some sort of load-balancing service, I looked at the TLS certificates in use by vsFTPd. They were all self-signed:

- 81.19.135[.]21 = 44102.example.ru, valid from Aug 06 2023 22:49:51 GMT-0400

- 81.19.135[.]25 = 14868.example.ru, valid from Aug 05 2023 23:48:55 GMT-0400

- 81.19.135[.]31 = 33916.example.ru, valid from Aug 05 2023 23:48:08 GMT-0400

I included the initial date for the certificate. As you can see, they are roughly an hour apart from each other. This implies that CL0P was prestaging these boxes about 10 days before they planned to release their first magnet links and five days before they publicly announced their intention to shift to this distribution method.

Using these patterns, I extended my search for certificates with an example.ru in their Common Name (CN) value that were observed to have FTP. I identified another host on this same subnet (shown in Figure 13) that exhibits similar features but has not yet shown up in the peering information.

You can see the same behavior where visibility is lost on the SSH port on Aug. 6, 2023, and the FTP port becomes active on Aug. 7, 2023. This aligns with the rest of what we’ve observed.

- 81.19.135[.]11 = 43577.example.ru, valid from Aug 06 2023 23:03:31 GMT-0400

Also notable on this host is the presence of Windows services two months earlier, as shown in Figure 14. This implies that the VPS was repurposed from Windows to a *nix-based machine within that time frame.

There is a lot of orchestration required to effectively host as much data as they’ve stolen. It might be that the IP address ending in 11 is being prepped to host further victim files.

The two IP addresses ending in 25 and 31 have victims that were announced early in the release process, either on August 15 or a few days after. Whereas the IP address ending with 21 started to get usage on victim announcements beginning on August 24, and it has almost four times the number of observed victims as the others. This could just be a result of my ability to observe them, but it could also imply something is different about this box.

Seed Group 2

Another IP that stands out was also mentioned by Gary Warner on LinkedIn, who was looking at the same type of information regarding CL0P seeds. Below is a snippet from his post:

After Cl0p decided that no one was able to download their stolen data via .onion servers, they migrated to using bitTorrent.

Of course the problem with using bitTorrent, is that it becomes painfully obvious where the bad guys are hosting the stolen data. If one accesses the TORRENT and there is only one IP address offering 100% of the data, for the LARGER data sets, that is almost certainly hosting that the criminal acquired to serve the file from. (Not true for the tiny data sets -- for those the criminal can wait a short time for others to have 100% of the file and then disconnect their original location.)

Currently the main locations for "100%" sets are:

95.215.0[.]76 = AS34665 Petersburg Internet, St. Petersburg Russia

(hosting company offerings at pindc[.]ru)

I believe Highlander rules apply here and we might have to battle in a Pokémon gym later!

This IP address 95.215.0[.]76, shown in Figure 15, shares some similarities with the previous cluster. Specifically the usage of a BitTorrent client with the string Transmission 3.00 was in use, and the hosting provider is another Russian company.

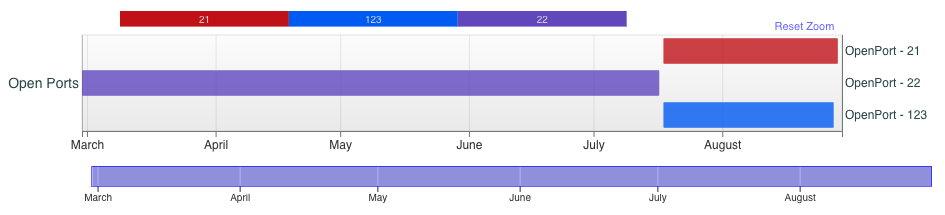

Sure enough, this seeding server (shown in Figure 16) exhibits behavior akin to the other cluster as it relates to services as well. However, the activity occurs almost a month before the other cluster. SSH services were observed up until July 17 and FTP services began appearing on July 18.

This is presumably an older box, and it also uses a different set of services to host FTP, leveraging ProFTPD. Likewise, the VPS is hosted in Saint Petersburg, Russia and it is announced from AS 34665 for Petersburg Internet Network (PIN) Datacenter.

This IP shares the below SSH Key with the IP address 95.215.1[.]221.

ecdsa-sha2-nistp256 AAAAE2VjZHNhLXNoYTItbmlzdHAyNTYAAAAIbmlzdHAyNTYAAABBBNos5CNsQHUKlXJSFDJKtPB/4FlkqW6R0crEQaONn3TJ2TICxQRUTh8DgITlLcidJf0pnn0zVMWwE6PsWDI3eZU=

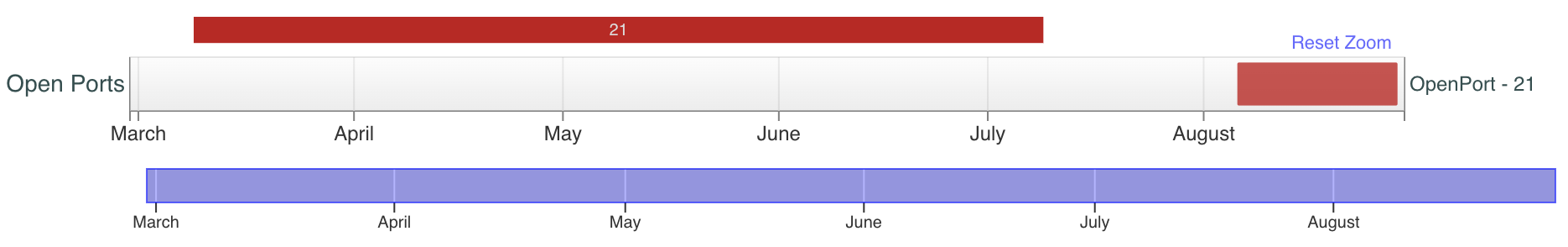

While I have not yet observed this IP address as a peer in my collection, I don’t know whether this is due to a visibility issue or that the box has yet to be used for hosting. It does share the same notable behavior with SSH and FTP, as shown in Figure 17.

Seed Group 3

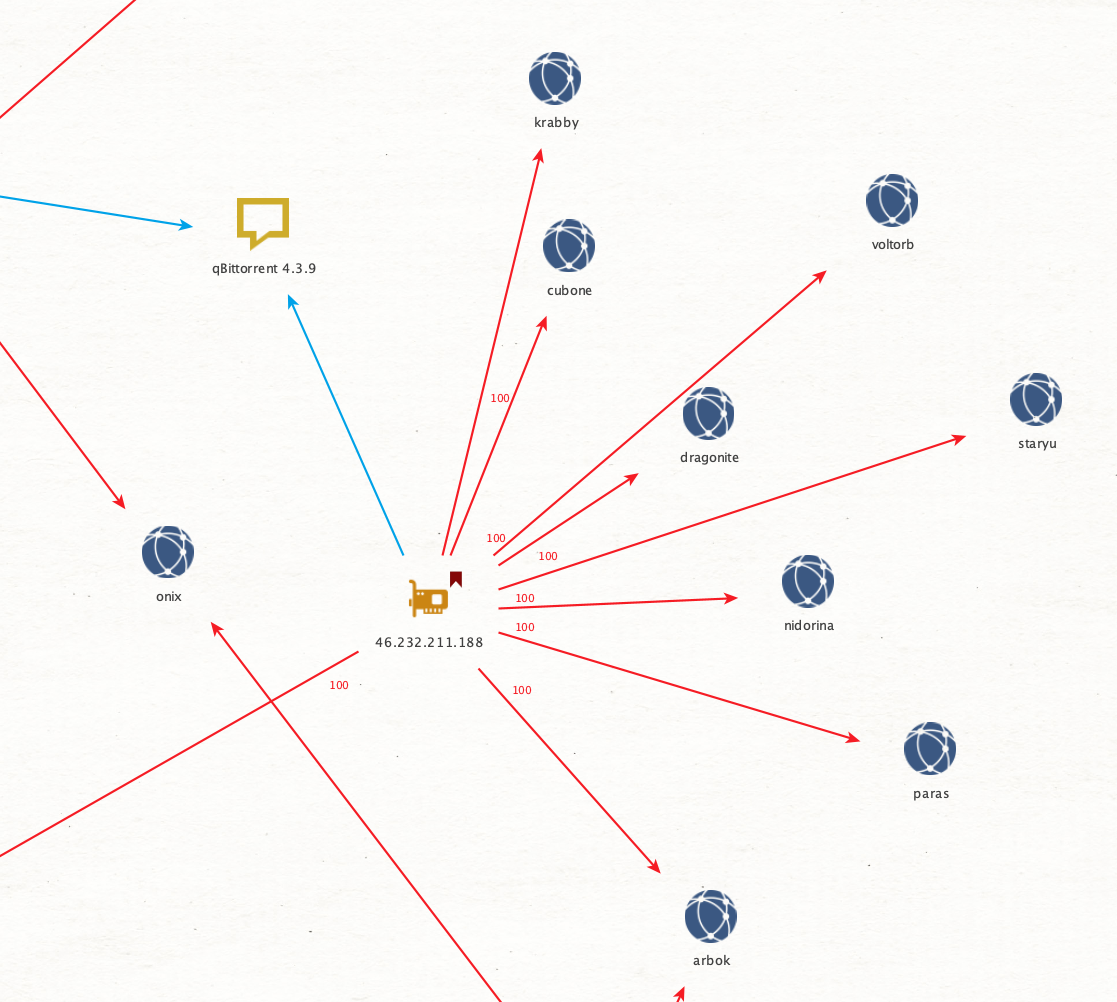

Applying these patterns to the other peers I’ve collected, the IP address 92.118.36[.]111 shown in Figure 18 stands out.

In this case, I’ve only observed it seeding a single torrent for Articuno at 100%. It’s located in Amsterdam, announced from AS 209132 for StreamHost.

Where this torrent aligns is that it uses the Transmission 3.00 client string, and it has similar FTP access beginning on August 9 (as shown in Figure 19).

One last note I’ll make is that while searching for this IP address, I stumbled across an AbuseIPDB report for the next IP ending in 112, shown in Figure 20. It showed a report of this address scanning for the MOVEit vulnerability in early June 2023, which is the vulnerability CL0P leveraged to steal all this data.

![Image 20 is a screenshot of abuse reports for IP address 92.118.36[.]112. This IP address has been reported a total of 203 times from 5 distinct sources. 92.118.36[.]112 was first reported on November 15, 2022, and the most recent report was two months ago. Old reports: the most recent abuse report for this IP addresses from two months ago. It is possible that this IP address is no longer involved in abusive activities. There's a table that includes the reporter, the date, the comment, and the categories. These the reporter is from America and their username is AdamCySec, the date is 06 June 2023, the comment is MOVEit vulnerability scanning, and the category is hacking.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/word-image-130278-20-1.png)

Whether this is related or not is unknown, but it’s an interesting coincidence if not.

Conclusion

By tracking and analyzing these types of shifts in leak site methodology, it gives us a unique insight into what a threat actor's mindset could be. By understanding the problem they face and how they are trying to solve it, it provides us with an opportunity for further analysis and research.

In this case, the result of this research is a handful of hosting servers out of Russia that hold enormous amounts of stolen victim data. We can expect much more to come in the following weeks.

Seed boxes are always worth keeping an eye on. When the adversary's mind is focused elsewhere, it’s a ripe environment for mistakes that lead to leaving us vital clues.

As for their trade craft, we know these threat actors are likely leveraging FTP to transfer the stolen files to the seed boxes. We also know that general visibility of SSH access shuts off immediately prior to the FTP services going live. This could mean multiple things, but top of mind is that they are likely prestaging the stolen data on the servers for quite some time before they make the announcement of the magnet link.

Likewise, the distribution of victim data across the seed boxes does not align with their announcement schedule. This would add weight to the theory that the data has persisted on the box for a while prior to the torrent’s creation. This could potentially be a technique they use to avoid seed tracking by having different victims announced at the same time yet seeded from different boxes.

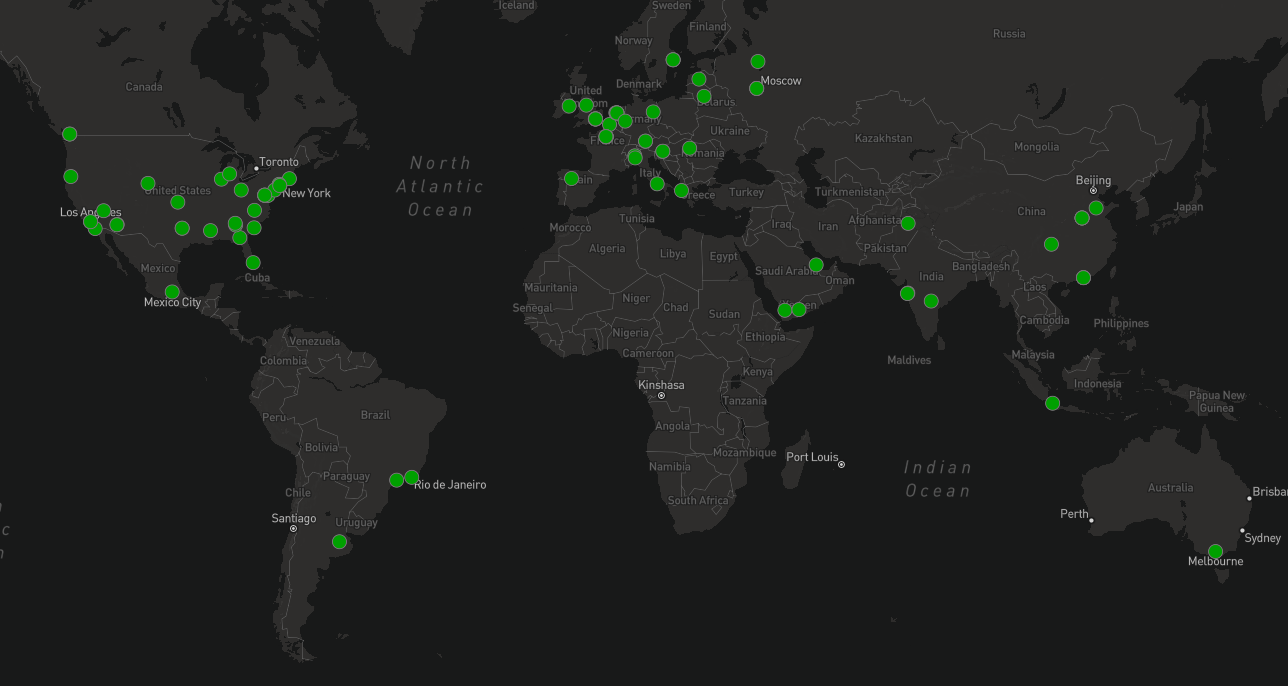

Before I sign off, I want to provide some additional observations of the collected data as it stands on Aug. 30, 15 days after this activity began.

The total number of original seeders is five.

- 81.19.135[.]21 (20 observed victims)

- 81.19.135[.]25 (5 observed victims)

- 81.19.135[.]31 (6 observed victims)

- 95.215.0[.]76 (9 observed victims)

- 92.118.36[.]111 (1 observed victim)

The total number of unobserved but likely seeders is two.

- 81.19.135[.]11

- 95.215.1[.]221

The total number of magnet links (each a victim): 192

The total number of successful 100% peering logs: 146

The total number of peers I connected with: 115

The top five peering clients for seeders are as follows:

- qBittorrent 4.5.4 (9)

- Transmission 3.00 (7)

- qBittorrent 4.4.1 (4)

- Transmission 2.9.3 (4)

- µTorrent 3.6.0 (4)

Figure 21 shows the distribution of peers, which is fairly global.

While I was not able to obtain all the file meta data before identifying a 100% seed and disconnecting, I did collect stats on what I observed.

In total, I received file data of just 41 of the victims (less than one-third of what I observed) totaling over 1.1 TB of data. The highest total file size I observed for any one victim was 127 GB with the low end being 2.8 MB and an average of 31 GB per victim.

There are many more victims to be released, and CL0P has remained relatively consistent in their release of their data, making good on all their threats. Additionally, some torrents for “well-known Pokémon” (in this analogy) were much more popular than others. Companies need to be aware that even if they do not pay the ransom, their data is a hot commodity for numerous reasons. None of those reasons are likely to be in their best interest.

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Protections and Mitigations

Palo Alto Networks customers can leverage a variety of product protections and updates to identify and defend against this threat.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Cortex XDR and XSIAM

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection from CL0P ransomware and other malware through Cortex XDR. Cortex XDR and XSIAM agents also help protect against post-exploitation activities associated with the MOVEit vulnerability using Behavioral Threat Protection, Anti-Webshell Protection and multiple additional security modules.

Additionally, Cortex Analytics has multiple detection models that help detect post-exploitation activities, with other relevant coverage by the Identity Analytics and Identity Threat Detection and Response (ITDR) modules.

Cortex Xpanse

Cortex Xpanse customers can identify external facing instances of the application through the “MOVEit Transfer” attack surface rule. The rule is available to all customers with a default state of “On.”

Cortex Xpanse has also released a new event in our Threat Response Center focused on the management of MOVEit exposures and additional remediation guidance and threat details related to MOVEit Transfer.

All Cortex Xpanse detection capabilities are also available for XSIAM customers who also have the ASM module.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh