read file error: read notes: is a directory 2023-7-28 21:0:53 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:35 收藏

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Threat actors seeking new ways to get their creations past victims’ defenses are increasingly turning to sending ransomware through URLs. They are also using increasingly dynamic behaviors to deliver their ransomware. In addition to treading the well-worn path of using polymorphic versions of their ransomware, threat actors often rotate hostnames, paths, filenames or a combination of all three to widely distribute ransomware.

We’ll show our findings on how threat actors are distributing ransomware via URLs, as well as discussing the following aspects of this data:

- How threat actors are abusing hosting providers and top level domains

- How threat actors are abusing public hosting, social media and sharing services

- How threat actors rotate hostnames, paths or filenames in URLs using several case studies

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers with Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security subscriptions are protected against malicious ransomware campaigns similar to the ones described in this article. All the mentioned ransomware samples are also covered by WildFire products.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Ransomware, Web Hosting |

Table of Contents

Prevalence of Web Browsing-Delivered Ransomware

Delivery Protocol of Ransomware

Ransomware Family Distributions

Web Hosting Infrastructure

Domain Distribution

Abuse of Public Hosting, Social Media and Sharing Services

Ransomware Campaigns and Case Studies

Rotating Ransomware Using the Same URL

Rotating Hostnames for the Same Ransomware File

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Indicators of Compromise

URLs

SHA-256 Hashes

Prevalence of Web Browsing-Delivered Ransomware

Delivery Protocol of Ransomware

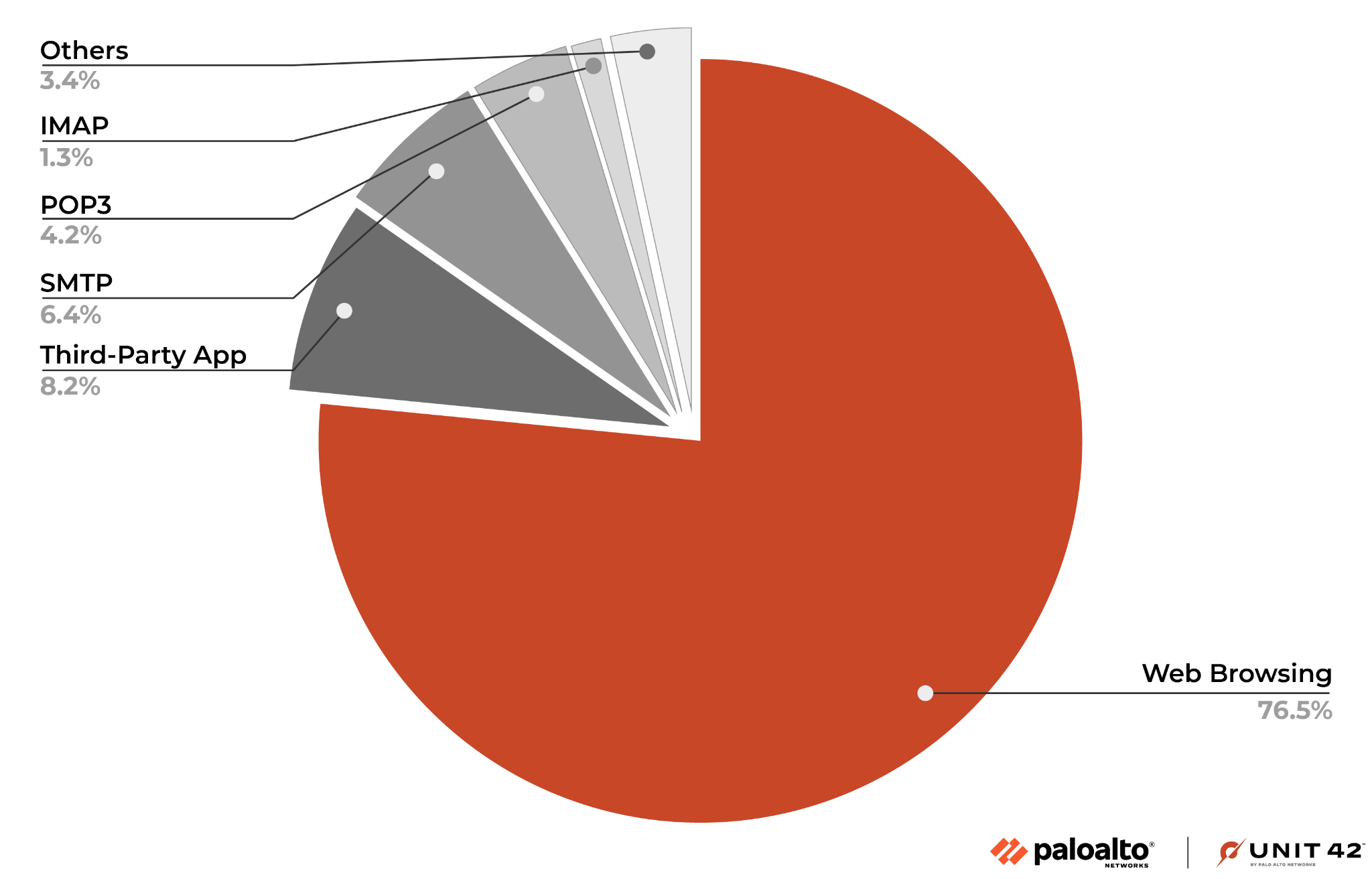

The three most popular methods of delivery for ransomware are through URLs, emails and third-party apps. People encounter ransomware delivered by URLs when they browse a site themselves, or if malware or other software surreptitiously placed on a compromised system accesses it. Ransomware delivered through email arrives as an attachment in the email itself rather than a ransomware URL included in the body of an email.

In 2021, Unit 42 published an article discussing trends in ransomware delivery methods. At that time, email attachments (e.g., SMTP and POP3 protocols) were the most widely-used channel for distributing ransomware. More recently, our analysis of ransomware samples from the entire year of 2022 revealed a shift in the primary entry vector for ransomware infections (as shown in Figure 1). URL or web browsing has emerged as the leading method for ransomware delivery, accounting for over 77% of cases.

Ransomware delivery through emails has decreased in prevalence to be the second most popular method, comprising almost 12% of the total.

Within the URLs that are used to deliver ransomware, we observed some notable trends including ransomware hosting URLs being used in various polymorphic forms to increase the agility of attacks. For example, threat actors have been observed both rotating different URLs to host the same ransomware (e.g., hxxp://oddsium[.]com/g76dbf and hxxp://clicktoevent[.]com/g76dbf?lrebib=kvqqhaohs) and using the same URL to deliver different ransomware (e.g., rgyui[.]top/dl/build.exe). We discuss various recent tactics in detail in the ransomware campaigns and case studies section below.

Ransomware Family Distributions

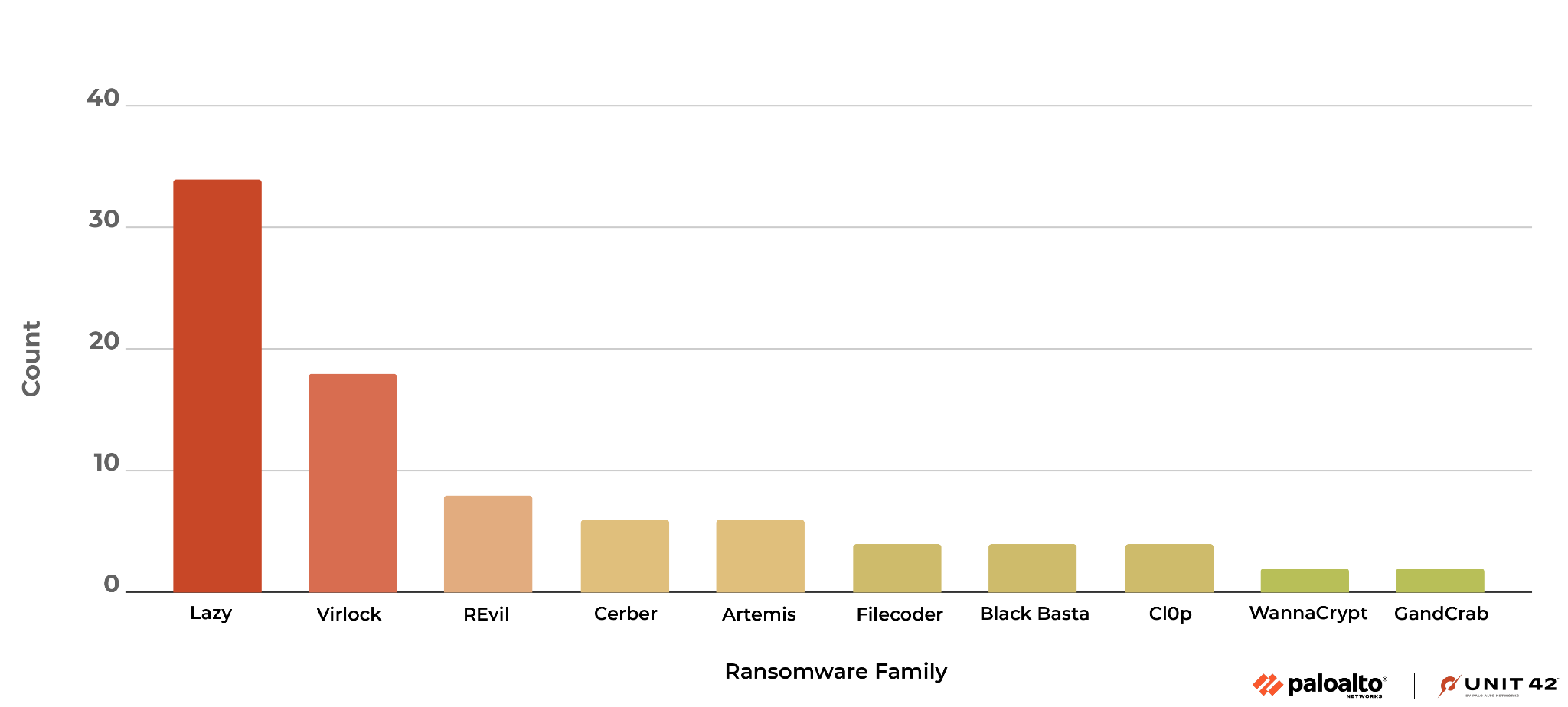

We also observed a variety of different families in the traffic we captured with our URL-based ransomware detection service. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the URLs in the top 10 ransomware families we observed in the last quarter of 2022. Lazy and Virlock ransomware, which have been in circulation for years, made up over 50% of the ransomware we observed.

Web Hosting Infrastructure

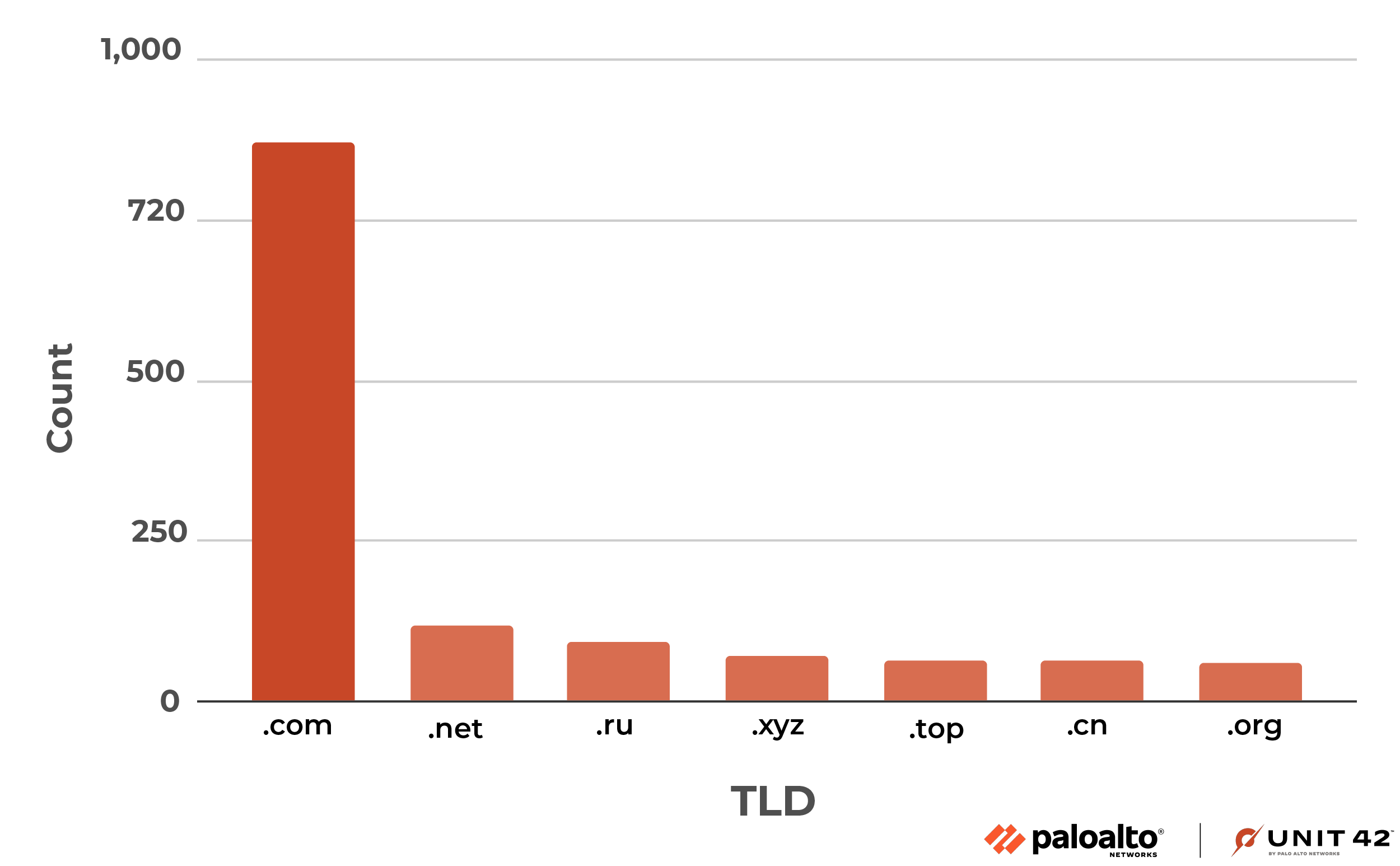

Between October and December 2022, our Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security services detected over 27,000 unique URLs and hostnames hosting ransomware. In this section, we analyze and provide insights into the hosting infrastructure of 7,000 random samples from these ransomware hosting URLs, which consist of 3,335 domains.

Domain Distribution

As we analyzed the hosts of ransomware URLs, we were concerned to see that (as of the end of December 2022) more than 20% of the URLs we observed were still active days or weeks after our detectors flagged them. Most of these URLs are compromised websites, and have likely gone undetected by site owners.

Figure 3 shows the most commonly abused top-level domains (TLDs), where the count shows the number of second level domains (2LDs). Aside from the expected abuse of generic top-level domains (gTLDs) (e.g., .com, .net, .org, .xyz, .top and .mobi) due to them comprising the lion’s share of the domain market, it is noteworthy to observe that attackers also abused country code top-level domains (ccTLDs) including .ru, and .cn, possibly indicating that these countries have less strict policies in place for registration of domains.

Abuse of Public Hosting, Social Media and Sharing Services

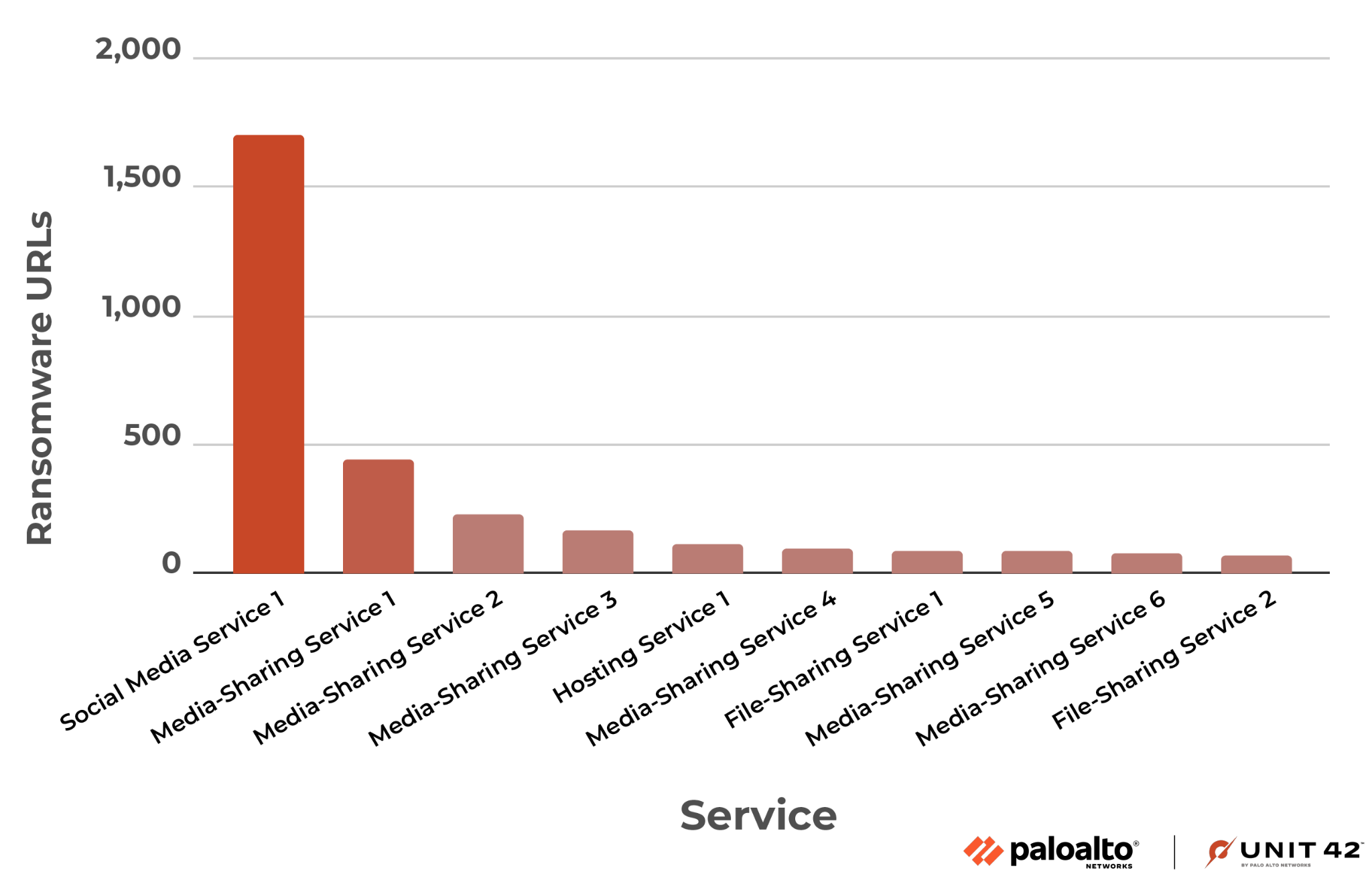

Threat actors often abuse, take advantage of or subvert legitimate products for malicious purposes. This does not necessarily imply a flaw or malicious quality to the legitimate product being abused.

Figure 4 shows the most commonly abused public hosting, social media and sharing services. Attackers usually create subdomains or paths under these popular services to reach a wider audience and to stay under the radar. These URLs are likely to fall through the cracks of many existing URL blocking services due to the good reputation involved with these services.

We analyzed the remaining 641 second-level domains hosting ransomware that are not abusing public hosting, social media or sharing services. We observed that 64% (547) of these domains were registered two or more years earlier and, according to passive DNS footprints, these domains were visited on average 215,892 times in the last six months.

Long lived domains coupled with consistently high DNS footprints indicate that these were compromised benign domains. Attackers take advantage of the trust in these websites to slip through people’s defenses.

Ransomware Campaigns and Case Studies

We observed a lot of different threat actors exhibiting differing campaign behaviors within our detections. For some campaigns, the attackers rotated different ransomware files with the same URLs. For other campaigns, the attackers rotated different URLs delivering the same ransomware.

Some attackers rotate both URLs and ransomware files. The same ransomware can be delivered through multiple URLs, and the same URL can deliver multiple ransomware variants, or even other types of malware (e.g., wipers, stealers or loaders).

Rotating Ransomware Using the Same URL

During our analysis of ransomware campaigns, we observed instances where a single URL or a group of URLs consistently delivers ransomware with a different SHA-256 hash value with each visit. This technique likely serves to evade hash-based blocking efforts.

In some cases, a single URL is used to distribute hundreds of distinct versions of ransomware. For example, in one STOP/DJVU ransomware campaign we captured, we identified over 800 different ransomware samples delivered through 14 different URLs.

Example URLs:

- miiwes[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- rgyui[.]top/dl/build.exe

- rgyui[.]top/dl/build2.exe

- rgyui[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- uaery[.]top/dl/build.exe

- uaery[.]top/dl/build2.exe

- uaery[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/build.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/build2.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- ex3mall[.]com/files/1/build3.exe

- spaceris[.]com/files/1/build3.exe

- bihsy[.]com/files/1/build3.exe

- ugll[.]org/files/1/build3.exe

SHA-256 hashes for example ransomware files delivered:

- 0708d5027c26f96f5bf81b373348346149511a4b9f11391a979159185371bcc5

- 9921cc50e6272053814c7fe2ab5ae566a9deaebc9c0412c8b518313eee65d9d9

- d05a67845680af53a1efe0d852aa7ab85ad97e76cc8aaa62b1aad70288665026

We also observed that some of the attackers use stealers and loaders (e.g., Racoon Stealer and Smoke Loader) as the initial stepping stones for the ransomware attack. With stealers deployed on a compromised environment, ransomware actors are enabled to get access to the environment.

Below is one loader campaign we identified, which is associated with the ransomware campaign above.

For example, the loader with SHA-256 4e1f743b60d65732d43e6a8c064016369a2cb6d03e81e04e114ed6a31297a2a7 is delivered through https://privacy-tools-for-you-780[.]com/downloads/toolspab3.exe. During execution, it contacts zerit[.]top/dl/buildz.exe from the above ransomware campaign to load ransomware binaries.

Similar to the ransomware delivery campaign above, the attacker keeps rotating the loader samples with a limited number of URLs. One URL could trigger the download of hundreds of different loader samples when visited at different times.

Example URLs:

- https://coin-coin-coin-2[.]com/downloads/toolspab2.exe

- https://coin-coin-coin-2[.]com/downloads/toolspab4.exe

- https://data-host-file-16[.]com/downloads/toolspab2.exe

- https://host-coin-data-1[.]com/downloads/toolspab1.exe

- https://privacy-tools-for-you-453[.]com/downloads/toolspab4.exe

- https://privacy-tools-for-you-780[.]com/downloads/toolspab3.exe

We observed that all the domains are registered with the same email radamir[.][email protected][.]com. Using this information allowed us to identify other malicious infrastructure and malware delivery URLs related to this activity.

While most of the URLs mentioned above are hosted on public cloud infrastructure, the attacker is using geographically distributed locations, such as 34[.]69[.]12[.]51 (in Iowa), 34[.]65[.]61[.]83 (in Europe) and 34[.]106[.]70[.]53 (in Utah), possibly to increase the coverage and agility of the attack.

All of these domains are also related to a threat actor called superstar75737 who sold access to Raccoon Stealer logs on a Russian-speaking cybercrime forum, exploit[.]in, in November 2022.

Example SHA-256 hash values of the malware delivered by this campaign:

- 168d41799cdb359a86c7e28e4b3eee3494270ec6e2884452dd61134b627b1c68

- 8a56cecfe36b7c105401fd246f8f3ba97bdc4d1db776eaa4991fcedf8aaaaa52

- ff6d6f616687fac25a1d77e52024838239e9a3bbb7b79559b0439a968ac384fe

- ba8533bd8118ec6881e25e4af2e2101996b4a9aef3f1f1931423bff03da0ace5

- 4e1f743b60d65732d43e6a8c064016369a2cb6d03e81e04e114ed6a31297a2a7

Rotating Hostnames for the Same Ransomware File

Another tactic frequently used by attackers is to distribute the same ransomware binary from different hostnames. It’s possible that this is done to avoid static blocklist-based URL blocking services and to evade takedown.

The following example shows a campaign (TeslaCrypt) that uses this tactic, possibly to evade detection.

Example URLs for the first campaign with the same SHA-256:

- http://oddsium[.]com/g76dbf

- http://veterinary-surgeons[.]net/g76dbf?grpvldcmq=pnstptslwh

- http://clicktoevent[.]com/g76dbf?lrebib=kvqqhaohs

SHA-256: 12d3077c923bc12aff8c2f3d04f96db427d841b185fa84a0a151d882cb3f08f8

This sample was originally observed in 2016. However, it is still being actively reused with new delivery URLs.

Conclusion

As ransomware operators continue to probe victim’s defenses using a revolving set of tactics, these threats require a defense-in-depth strategy where both binaries and URLs are analyzed to proactively detect ransomware to keep networks secure.

We observed a wide variety of tactics threat actors used to distribute ransomware on the web. Ransomware binaries are often delivered from compromised websites, which should serve as a reminder for site administrators to maintain up-to-date web applications to minimize the impact of known vulnerabilities.

Since its inception in October 2022, the Palo Alto Networks Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security product releases have automatically blocked over 2,000 sessions involving ransomware URLs daily. Our models also detect over 600 ransomware URLs per day.

In fact, over 49% of those ransomware URLs detected by our service are blocked from our customer traffic before reaching their devices. This indicates that our detectors identify active ransomware that is currently in circulation.

Our recent product release of a ransomware category of URLs is part of a continuous effort by Palo Alto Networks to secure our customers by more deeply analyzing URLs. This adds to the portfolio of static/dynamic analysis and deep learning-based detection of ransomware capabilities we already provide.

We have also trained a deep-learning model to identify ransomware based on the lexical patterns in the URLs. The model can search for words or chunks of text that frequently appear in malicious campaigns.

An added benefit of using these lexical similarities is that newly detected ransomware URLs can be traced back to patterns in the training samples. This serves as an explanation for detections and helps to identify campaigns of newly detected URLs.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers with Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security subscriptions are protected against malicious ransomware campaigns similar to the ones described in this blog. All the mentioned ransomware samples are also covered by WildFire products.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kyle Wilhoit and Doel Santos for their assistance in verifying ransomware samples and for their valuable feedback. We would also like to thank Billy Melicher, Alex Starov, Wenjun Hu, Billy Hewlett and Daiping Liu for their valuable feedback and support.

Indicators of Compromise

URLs

Teslacrypt Campaign URLs

- oddsium[.]com/g76dbf

- clicktoevent[.]com/g76dbf?lrebib=kvqqhaohs

- http://veterinary-surgeons[.]net/g76dbf?grpvldcmq=pnstptslwh

- rgyui[.]top/dl/build.exe

AI-Detected URLs for MSIL.Blocker, Xorist and Hidden Tear Ransomware

- s25[.]stazeni[.]ua[.]rs/download/ill2a7r2hsyufadaluvhv71xuuhubneg

- s30.stazeni[.]ua[.]rs/download/p1rcwy69oe09csyefqj4j9fmhmx1hamq

- s24.stazeni[.]ua[.]rs/download/5pg08rc9pxvy743ncrn30d2zylf2l12a

- s20.stazeni[.]ua[.]rs/download/z2guqagslno4pb06hnpuy1ocf7wstfxf

URLs for STOP/DJVU Ransomware/Stealer

- miiwes[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- rgyui[.]top/dl/build.exe

- rgyui[.]top/dl/build2.exe

- rgyui[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- uaery[.]top/dl/build.exe

- uaery[.]top/dl/build2.exe

- uaery[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/build.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/build2.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

- ex3mall[.]com/files/1/build3.exe

- spaceris[.]com/files/1/build3.exe

- bihsy[.]com/files/1/build3.exe

- ugll[.]org/files/1/build3.exe

Smoke Loader Campaign URLs

- https://privacy-tools-for-you-780[.]com/downloads/toolspab3.exe

- https://coin-coin-coin-2[.]com/downloads/toolspab2.exe

- https://coin-coin-coin-2[.]com/downloads/toolspab4.exe

- https://data-host-file-16[.]com/downloads/toolspab2.exe

- https://host-coin-data-1[.]com/downloads/toolspab1.exe

- https://privacy-tools-for-you-453[.]com/downloads/toolspab4.exe

- https://privacy-tools-for-you-780[.]com/downloads/toolspab3.exe

- zerit[.]top/dl/buildz.exe

SHA-256 Hashes

MSIL.Blocker

- 647b12dd3809b62d8b051ec643a1c5d26c32ec3397266c76e6f58e3894e39c4b

Xorist Ransomware

- 08c524509178aa6a93de9861790804266289fbed704af269f3c4ddde75518b15

- d1ad11b98dd193b107731349a596558c6505e51e9b2e7195521e81b20482948d

Hidden Tear Ransomware

- 87102e5614509da4c59b134861130708f239b68d1e062d08d1e71464c8041326

STOP/DJVU Ransomware/Stealer

- 0708d5027c26f96f5bf81b373348346149511a4b9f11391a979159185371bcc5

- 9921cc50e6272053814c7fe2ab5ae566a9deaebc9c0412c8b518313eee65d9d9

- d05a67845680af53a1efe0d852aa7ab85ad97e76cc8aaa62b1aad70288665026

Smoke Loader

- 4e1f743b60d65732d43e6a8c064016369a2cb6d03e81e04e114ed6a31297a2a7168d41799cdb359a

- 86c7e28e4b3eee3494270ec6e2884452dd61134b627b1c688a56cecfe36b7c105401fd246f8f3ba9

- 7bdc4d1db776eaa4991fcedf8aaaaa52ff6d6f616687fac25a1d77e52024838239e9a3bbb7b79559

- b0439a968ac384feba8533bd8118ec6881e25e4af2e2101996b4a9aef3f1f1931423bff03da0ace5

Teslacrypt

- 12d3077c923bc12aff8c2f3d04f96db427d841b185fa84a0a151d882cb3f08f8

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh