Executive SummaryRussia’s Fo 2023-7-12 18:0:21 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:37 收藏

Executive Summary

Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service hackers, which we call Cloaked Ursa (aka APT29, UAC-0029, Midnight Blizzard/Nobelium, Cozy Bear) are well known for targeting diplomatic missions globally. Their initial access attempts over the past two years have predominantly used phishing lures with a theme of diplomatic operations such as the following:

- Notes verbale (semiformal government-to-government diplomatic communications)

- Embassies’ operating status updates

- Schedules for diplomats

- Invitations to embassy events

These types of lures are generally sent to individuals who handle this type of embassy correspondence as part of their daily jobs. They are meant to entice targets to open the files on behalf of the organization they work for.

Recently, Unit 42 researchers observed instances of Cloaked Ursa using lures focusing on the diplomats themselves more than the countries they represent. We have identified Cloaked Ursa targeting diplomatic missions within Ukraine by leveraging something that all recently placed diplomats need – a vehicle.

We observed Cloaked Ursa targeting at least 22 of over 80 foreign missions located in Kyiv. While we don’t have details on their infection success rate, this is a truly astonishing number for a clandestine operation conducted by an advanced persistent threat (APT) that the United States and the United Kingdom publicly attribute to Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).

Our assessment that Cloaked Ursa is responsible for these lures is based on the following:

- Similarities to other known Cloaked Ursa campaigns and targets

- Use of known Cloaked Ursa TTPs

- Code overlap with other known Cloaked Ursa malware

These unconventional lures are designed to entice the recipient to open an attachment based on their own needs and wants instead of as part of their routine duties.

The lures themselves are broadly applicable across the diplomatic community and thus are able to be sent and forwarded to a greater number of targets. They’re also more likely to be forwarded to others inside of an organization as well as within the diplomatic community.

Overall, these factors increase the odds of a successful compromise within targeted organizations. While not likely to fully supplant diplomatic operations-themed lures, these lures focusing on individuals do provide Cloaked Ursa with new opportunities and a broader range of susceptible potential espionage targets.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the types of threats discussed in this article by products including:

- Cortex XDR

- WildFire

- Cloud-Delivered Security Services for the Next-Generation Firewall, including Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security

If you believe you have been compromised, the Unit 42 Incident Response team can provide a personalized response.

Table of Contents

BMW for Sale

Turkish Diplomats: Humanitarian Assistance for Earthquake

Conclusion

Indicators of Compromise

Samples

URLs

Known Email Senders

BMW Payload: Dropbox and MS Graph API Tokens and Secrets

Additional Resources

Appendix

Technical Analysis of BMW Campaign

Technical Analysis of Turkey Campaign

BMW for Sale

One of the most recent of these novel campaigns that Unit 42 researchers observed appeared to use the legitimate sale of a BMW to target diplomats in Kyiv, Ukraine, as its jumping off point.

The campaign began with an innocuous and legitimate event. In mid-April 2023, a diplomat within the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs emailed his legitimate flyer to various embassies advertising the sale of a used BMW 5-series sedan located in Kyiv. The file was titled BMW 5 for sale in Kyiv - 2023.docx.

The nature of service for professional diplomats is often one that involves a rotating lifestyle of short- to mid-term assignments at postings around the world. Ukraine presents newly assigned diplomats with unique challenges, being in an area of armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

How do you ship personal goods, procure safe accommodations and services, and arrange for reliable personal transportation while in a new country? The sale of a reliable car from a trusted diplomat could be a boon for a recent arrival, which Cloaked Ursa viewed as an opportunity.

We assess that Cloaked Ursa likely first collected and observed this legitimate advertising flyer via one of the email’s recipients’ mail servers being compromised, or by some other intelligence operation. Upon seeing its value as a generic yet broadly appealing phishing lure, they repurposed it.

Two weeks later, on May 4, 2023, Cloaked Ursa emailed their illegitimate version of this flyer to multiple diplomatic missions throughout Kyiv. These illegitimate flyers (shown in Figure 1) use benign Microsoft Word documents of the same name as that sent by the Polish diplomat.

The key difference with these illegitimate versions is that if a victim clicks on a link offering “more high quality photos,” a URL shortener service (either t[.]ly or tinyurl[.]com) will redirect them to a legitimate site. This site would have been coopted by Cloaked Ursa, resulting in the download of a malicious payload.

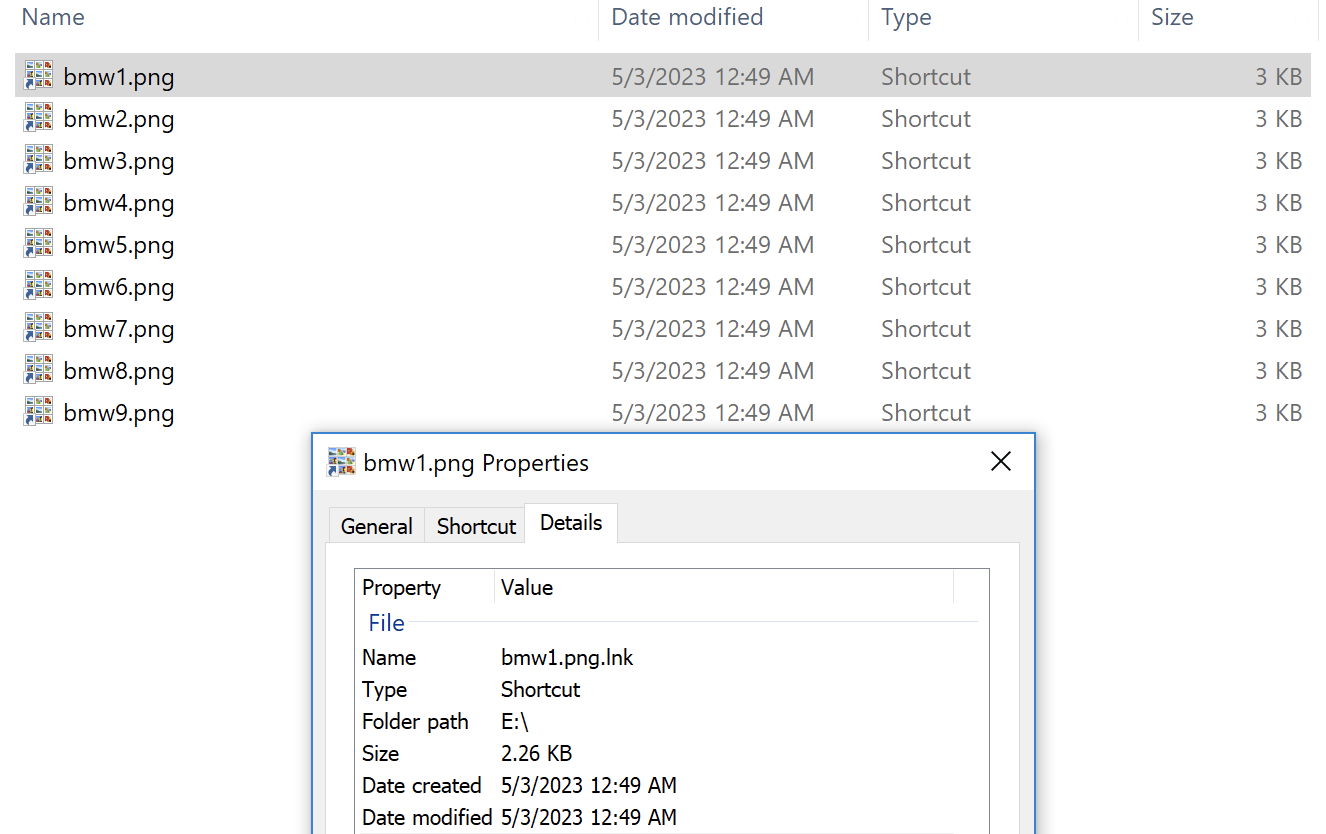

When a victim attempts to view any of the “high quality photos” (shown in Figure 2) in the download, the malware executes silently in the background while the selected image displays on the victim’s screen.

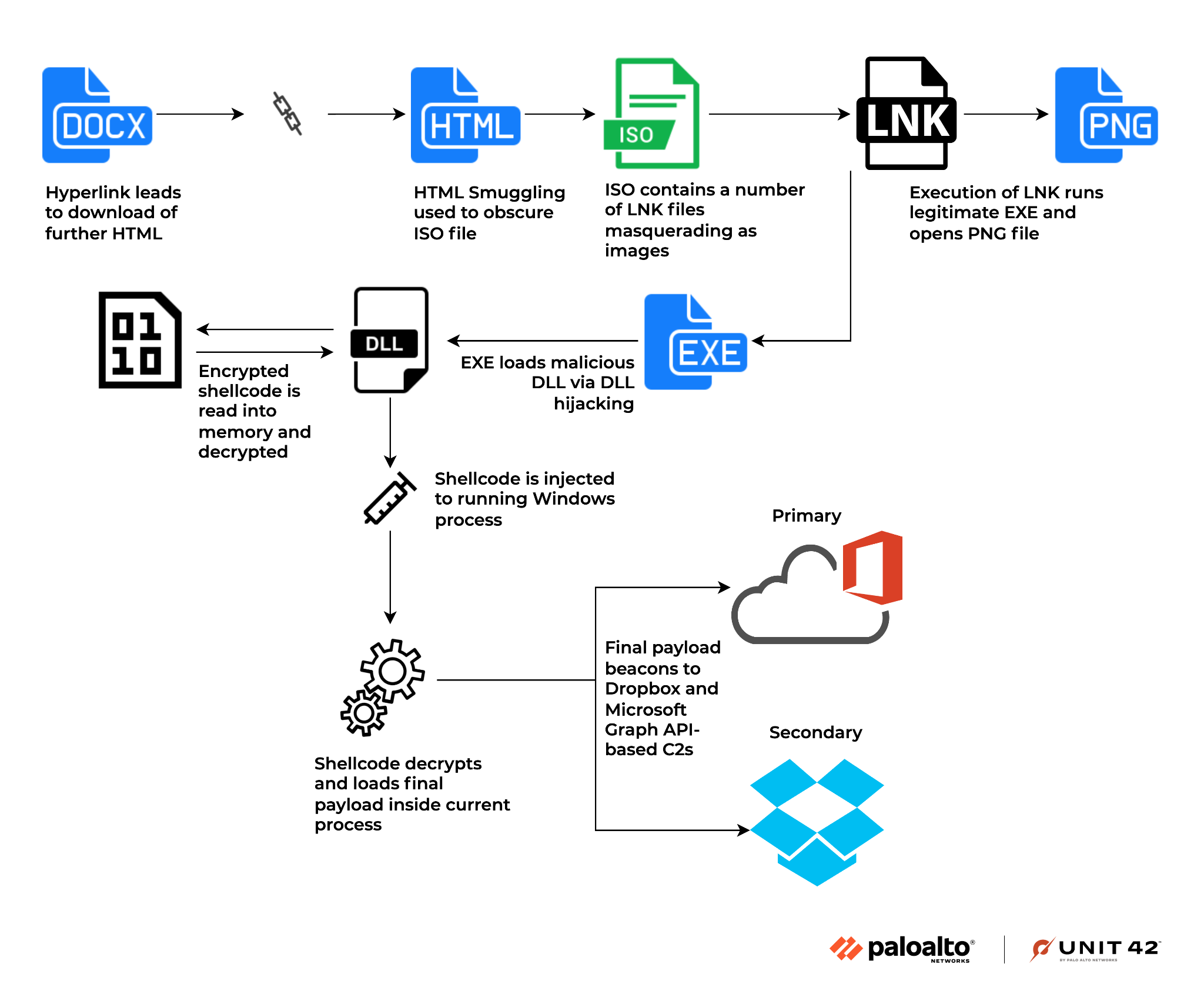

Figure 3 illustrates the full execution flow.

These pictures are actually Windows shortcut files masquerading as PNG image files.

We’ve observed two versions of these illegitimate flyers. The only difference between the two is the shortened URL used in each case. The URLs ultimately redirect the victim to the same coopted site (hxxps://resetlocations[.]com/bmw.htm).

At the time of this writing, one of the flyer versions (SHA256: 311e9c8cf6d0b295074ffefaa9f277cb1f806343be262c59f88fbdf6fe242517) is detected as malicious by multiple vendors according to VirusTotal, while the other version (SHA256: 8902bd7d085397745e05883f05c08de87623cc15fe630b36ad3d208f01ef0596) is not detected. For a full overview of the malware, please refer to the Appendix.

Overall, we observed Cloaked Ursa targeting at least 22 of over 80 foreign missions located in Kyiv in this campaign, as shown in Table 1. The actual number targeted is likely higher. This is staggering in scope for what generally are narrowly scoped and clandestine APT operations.

|

Known Embassies in Kyiv Targeted by Cloaked Ursa in BMW Campaign |

||

|

|

|

Table 1. Known embassy targets of BMW campaign.

For the activity we observed, Cloaked Ursa used publicly available embassy email addresses for approximately 80% of the targeted victims. The remaining 20% consisted of unpublished email addresses not found on the surface web.

This indicates that attackers likely also used other collected intelligence to generate their victim target list, to ensure they were able to maximize their access to desired networks. The majority of the targeted organizations in this campaign were embassies. However, we also observed Cloaked Ursa targeting both Turkish Ministry of Trade representatives in Ukraine (via their ticaret[.]gov[.]tr work emails) and their embassy in the BMW campaign.

While there were a handful of emails sent directly to individuals’ work addresses within the campaign, the majority of the targeted emails consisted of general inboxes for the embassy, such as [email protected][.]gov[.]xx. Despite the thought and detail put into targets for this campaign, at least two of the email addresses contained errors and never reached the intended targets. Overall, the use of these group inboxes likely increased the odds of the emails being reviewed and passed on to individuals within the embassies looking for transportation.

With a few of the embassies we observed being targeted, this was done via group emails hosted on free online webmail services. While these services offer some protection, they also outsource a portion of the security provided to targeted organizations and their employees to external entities. The use of free online webmail could have the unintended consequence of increasing a diplomatic organization’s difficulty in observing and understanding the totality of threats targeting it while also increasing its attack surface.

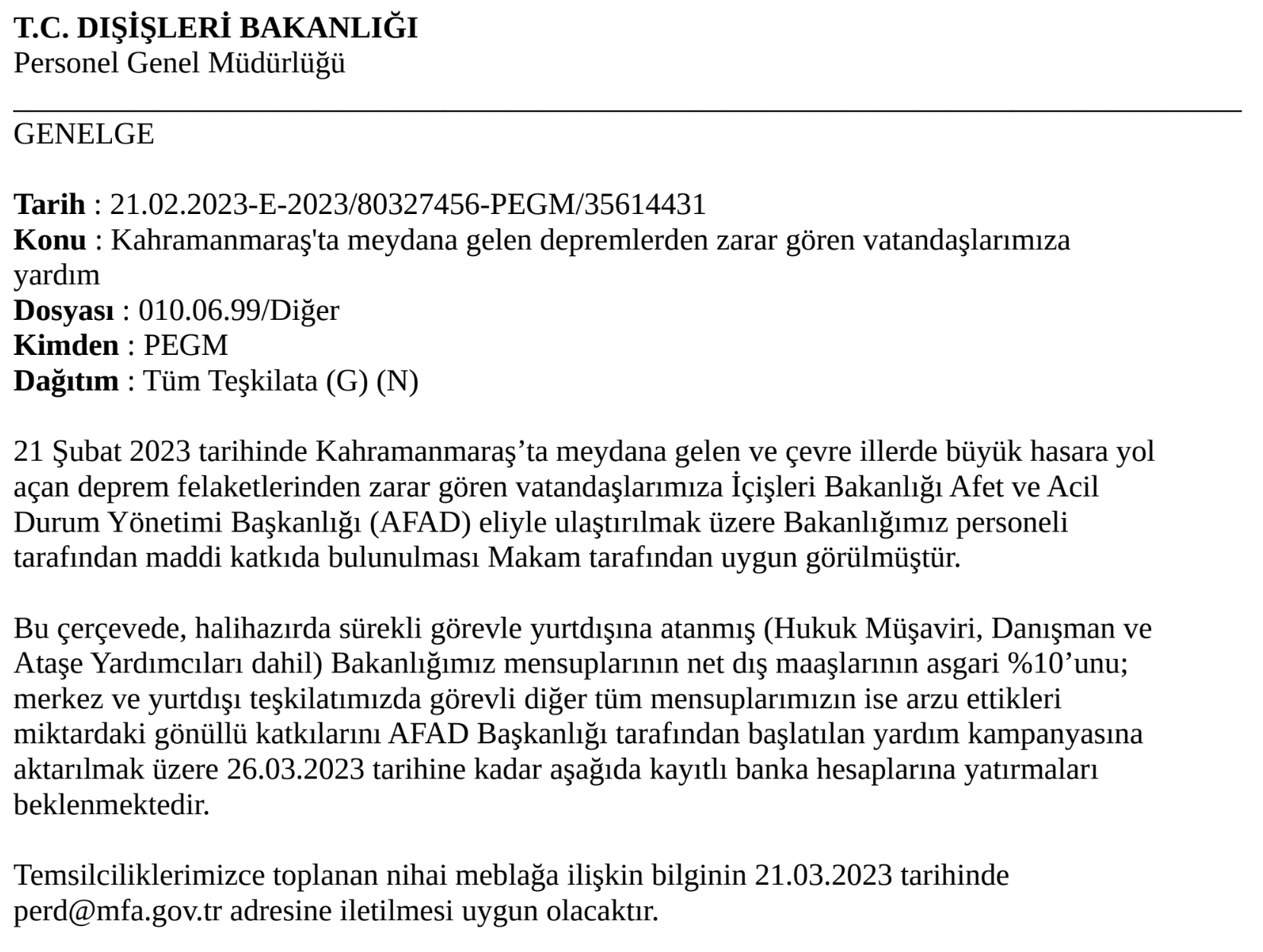

Turkish Diplomats: Humanitarian Assistance for Earthquake

Another of the novel Cloaked Ursa campaigns we observed likely targeted the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) earlier in 2023, within a February to March timeframe. While we were unable to obtain the malicious email lure associated with this campaign, we know that it related to a document that purported to be Turkish MFA guidance on humanitarian assistance pertaining to the Feb. 21, 2023, earthquake in Turkey. The earthquake in late February further ravaged a region already devastated by a massive earthquake two weeks earlier, which ultimately killed more than 50,000 and displaced more than 5.9 million people.

We were able to determine this second campaign targeting the MFA based on a PDF (shown in Figure 4) that was contained in a downloaded payload (SHA256: 0dd55a234be8e3e07b0eb19f47abe594295889564ce6a9f6e8cc4d3997018839 – for a full overview of the malware, please refer to the Appendix).

Not one to let a disaster and the highly sympathetic charge it generates go to waste, Cloaked Ursa likely saw a lure providing MFA guidance on humanitarian support for this tragedy as a way to ensure a high level of interest from their targets – these recipients would feel a patriotic obligation and would understand the MFA’s expectations to support their nation and its victims. In addition, given the timely and momentous nature of the lure, it was almost certainly forwarded by concerned employees to others in their organization who would be interested in the guidance.

Conclusion

Diplomatic missions will always be a high-value espionage target. Sixteen months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, intelligence surrounding Ukraine and allied diplomatic efforts are almost certainly a high priority for the Russian government.

As the above campaigns show, diplomats should appreciate that APTs continually modify their approaches – including through spear phishing – to enhance their effectiveness. They will seize every opportunity to entice victims into compromise. Ukraine and its allies need to remain extra vigilant to the threat of cyber espionage, to ensure the security and confidentiality of their information.

Recommendations

- Train newly assigned diplomats and employees to a diplomatic mission on the cybersecurity threats for the region prior to their arrival. This training should include the specific tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by APTs in that region.

- Always take extra precautions to observe URL redirection when using URL-shortening services.

- Always be cautious of downloads, even from seemingly innocuous or legitimate sites. APTs routinely co-opt legitimate sites or services for malicious purposes.

- Always take extra precautions with attachments that require a web browser to open. These types of attachments include the following file extensions: .hta, .htm, .html, .mht, .mhtml, .svg, .xht and .xhtml.

- Always verify file extension types to ensure you are opening the type of file you intend to. If the file extension does not match, or if it is attempting to obfuscate its nature, it is very likely malicious.

- When received as an attachment to an email, or when downloaded from a link within an email, always look for hidden files and directories in archives such as those with the extensions .zip, .rar, .7z, .tar and .iso. The presence of hidden files or directories could indicate the archive is malicious.

- Consider disabling JavaScript as a rule.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the types of threats discussed in this article by products including:

- Cortex XDR

- WildFire

- Cloud-Delivered Security Services for the Next-Generation Firewall, including Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks disclosed this activity to Microsoft and Dropbox.

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Samples

- 311e9c8cf6d0b295074ffefaa9f277cb1f806343be262c59f88fbdf6fe242517

- 8902bd7d085397745e05883f05c08de87623cc15fe630b36ad3d208f01ef0596

- 47e8f705febc94c832307dbf3e6d9c65164099230f4d438f7fe4851d701b580b

- 79a1402bc77aa2702dc5dca660ca0d1bf08a2923e0a1018da70e7d7c31d9417f

- 38f8b8036ed2a0b5abb8fbf264ee6fd2b82dcd917f60d9f1d8f18d07c26b1534

- 706112ab72c5d770d89736012d48a78e1f7c643977874396c30908fa36f2fed7

- c62199ef9c2736d15255f5deaa663158a7bb3615ba9262eb67e3f4adada14111

- cd4956e4c1a3f7c8c008c4658bb9eba7169aa874c55c12fc748b0ccfe0f4a59a

- 0dd55a234be8e3e07b0eb19f47abe594295889564ce6a9f6e8cc4d3997018839

- 60d96d8d3a09f822ded0a3c84194a5d88ed62a979cbb6378545b45b04353bb37

- 03959c22265d0b85f6c94ee15ad878bb4f2956a2b0047733edbd8fdc86defc48

URLs

- hxxp://tinyurl[.]com/ysvxa66c

- hxxp://t[.]ly/1IFg

- hxxps://resetlocations[.]com/bmw.htm

- hxxps://tinyurl[.]com/mrxcjsbs

- hxxps://simplesalsamix[.]com/e-yazi.html

- hxxps://www.willyminiatures[.]com/e-yazi.html

Known Email Senders

- [email protected][.]com

- [email protected][.]pl

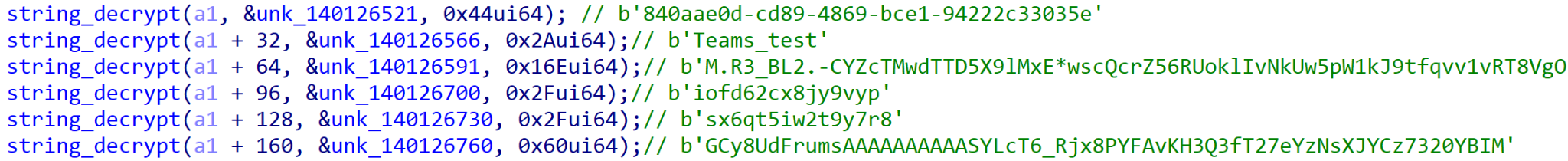

BMW Payload: Dropbox and MS Graph API Tokens and Secrets

- Teams_test

- 840aae0d-cd89-4869-bce1-94222c33035e

- M.R3_BL2.-CYZcTMwdTTD5X9lMxE*wscQcrZ56RUoklIvNkUw5pW1kJ9tfqvv1vRT8VgOb8uXtJTPB3E2CKV!pmm4V6DF8TRvo60QFCxMnUAnuv3jJ78TqHMdxPHONUDeI!B4DbLyg6ZjPZzghLXtmTZqzxOfpCUInOnhFJGoiL6kob7hKVhxm2dJQ9whK9zORxKg0FAnmd0tAR9lKJJaIUkVLcQ939EG2EKG9xsVVWwL04kX0092j7r2jo0rQR9Nqe4DuG0cRAMoODktAbTiuIsehkO5bM0ZuHsDuRr6mMoJrpwbqP0nt5PqJ*E7TS2scdYYOxnQ0mQ$$

- iofd62cx8jy9vyp

- sx6qt5iw2t9y7r8

- GCy8UdFrumsAAAAAAAAAASYLcT6_Rjx8PYFAvKH3Q3fT27eYzNsXJYCz7320YBIM

Turkey MFA Payload: Dropbox and MS Graph API Tokens and Secrets

- e0f94357-98c9-475d-94eb-27b6c74a6429

- mytestworkapp1

- M.R3_BL2.-CUanxFBYCxVzJ6hwSYPoLZ49NQ3X*y5rETt!aN*487MvafwQFn7kevSiXUwpGnHaquakM8vH6iESLDlXP38hmqQn98rRLvOzWwlKmD!8Xb5yEewCaa13S4Y1VyTIswo54Ez5ihRdUYCkYxkidMsZBn5!4icBZKpwC9hDW6G8OLcj8c2ZDtl8kUJ5PaX5TTDgXRzYdLPcqJFiNREjNg0*L569xMG1D14JpmjuO3HLBN2OclUv6c9FeuRwe5EuHA9aKhdqWkdjxWbnGGMgn9SnyDF7VSVCYT0*KBPNE!WYm*CXbE4jNTqJnkyPzvDJtj0OoA$$

- 3a1n71ujslwse9v

- 75vedbskd505jyk

- Hd0j7avNBxsAAAAAAAAAARq2fs5Ei8Z0-ahPPeB1McEek6NMzkGRmYHuxjsCZTfE

Additional Resources

- Espionage Campaign Linked to Russian Intelligence Services – Cybersecurity Emergency Response Team Poland (CERT.PL)

Cloaked Ursa / APT29 Phishing Tweet (March 10, 2023) – Palo Alto Networks, Unit 42 - IOCs: Cloaked Ursa / APT29 Phishing Tweet (March 10, 2023) – Palo Alto Networks, Unit 42

- Russian APT29 Hackers Use Online Storage Services, DropBox and Google Drive – Palo Alto Networks, Unit 42

Appendix

Technical Analysis of BMW Campaign

The hyperlinks found within the malicious BMW 5 for sale in Kyiv - 2023.docx flyers (SHA256: 311e9c8cf6d0b295074ffefaa9f277cb1f806343be262c59f88fbdf6fe242517 and (SHA256: 8902bd7d085397745e05883f05c08de87623cc15fe630b36ad3d208f01ef0596) lead to a site (hxxps://resetlocations[.]com/bmw.htm) that was offline in mid-June, but they originally retrieved a large HTA file. (SHA256: 47e8f705febc94c832307dbf3e6d9c65164099230f4d438f7fe4851d701b580b) This HTA file contains roughly 10 MB of Base64-encoded and XORed data, followed by JavaScript code.

The JavaScript code would first make a request to the same domain on the URI kll.php, before decoding the embedded data mentioned above and triggering the browser to download it using msSaveOrOpenBlob, or a mix of createElement and createObjectURL should msSaveOrOpenBlob fail. The downloaded file is assigned the name bmw.iso (SHA256: 79a1402bc77aa2702dc5dca660ca0d1bf08a2923e0a1018da70e7d7c31d9417f), matching the theme seen thus far.

Once downloaded, execution is reliant on the user clicking the downloaded file, which mounts the disk image to the system and opens up Windows File Explorer. This reveals nine total files masquerading as images, which are instead LNK shortcut files (shown in the execution flow diagram in Figure 3).

A hidden folder named $Recycle.Bin is created alongside the LNK files. This folder contains the real PNG images as well as three DLLs, an encrypted payload and a legitimate copy of Microsoft Word named windoc.exe.

If one of the LNK files is clicked, the following command line is executed. Note that the image name is changed depending on the LNK file clicked:

![]()

While windoc.exe is not malicious, it does attempt to load several DLLs on runtime and falls victim to DLL hijacking. As a result, it will load two of the three DLLs within its current directory, namely APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64.dll (SHA256: 38f8b8036ed2a0b5abb8fbf264ee6fd2b82dcd917f60d9f1d8f18d07c26b1534) and MSVCP140.dll. (SHA256: 706112ab72c5d770d89736012d48a78e1f7c643977874396c30908fa36f2fed7). The third DLL (Mso20Win32Client.dll) does not appear to be essential to the malware’s functioning and is added so that windoc.exe runs correctly, similarly to the DLL described below.

MSVCP140 is not digitally signed, but does not contain any malicious functionality. It appears to only contain a select few exports from a legitimate copy of MSVCP140. It’s likely that this was included to execute windoc.exe on systems that did not have Microsoft Visual C++ Redistributables – at least enough so that it would load APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64.

APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64, on the other hand, is a fairly obfuscated DLL. It leverages a large number of unnecessary assembly instructions, including the following, likely hindering decompilation efforts and slowing down analysis:

- Psllq

- Emms

- Pcmpeqd

- Punpckhbw

APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64 contains a number of anti-analysis techniques, including the following:

- Making sure its process name is set to windoc.exe

- Checking that the system has more than one processor

- Leveraging NtQueryObject to search for any existing Debug Objects, to check for the existence of a debugger

If these checks are all passed, the sample will proceed to open the encrypted payload file found within the ISO file, in this case named ojg2.px. (SHA256: c62199ef9c2736d15255f5deaa663158a7bb3615ba9262eb67e3f4adada14111). Once read into memory, it will decrypt the file using an XOR operation, which results in a secondary shellcode layer.

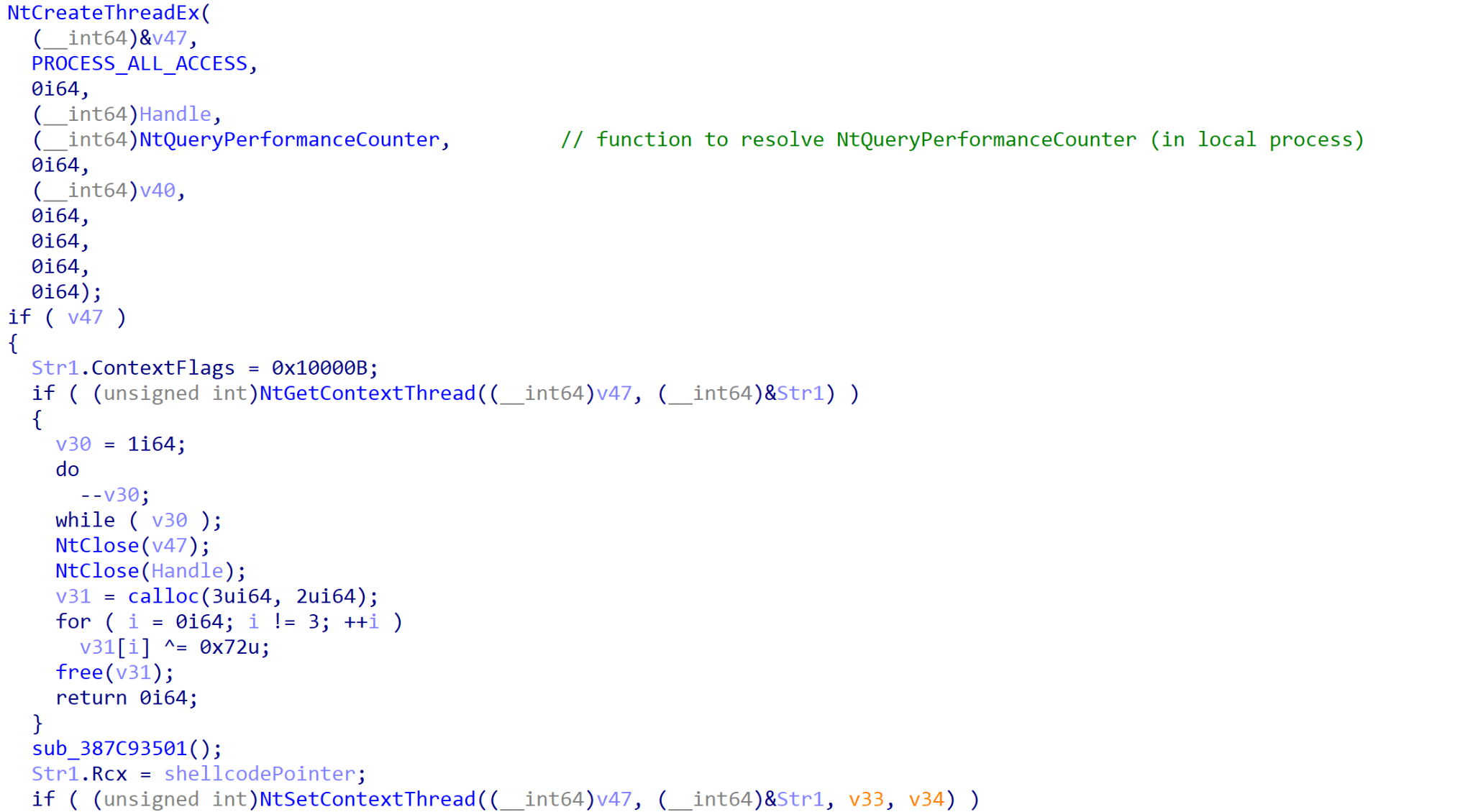

The shellcode is then injected into the first two active Windows processes that it can inject into, such as taskhost.exe or sihost.exe, using a technique that is somewhat similar to one previously used by Cloaked Ursa (as recently described by the Military Counterintelligence Service and CERT.PL).

First, the shellcode is mapped and copied into the remote process using NtMapViewOfSection before a new remote thread is created in a suspended state using NtCreateThreadEx. The interesting aspect of this injection technique is that instead of the created thread pointing to the shellcode entry point or any Windows API, it is given a start address of a function within the APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64 process. It’s possible that the authors did this to evade monitoring tools from identifying a newly created thread pointing to malicious shellcode.

Before the thread is resumed with NtResumeThread, APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64 will use NtGetContextThread and NtSetContextThread to modify the RCX register (which will contain the thread entry) to point to the entry point of the shellcode.

This results in the resumed thread calling RtlUserThreadStart, which will move the value in the RCX register to R9 before calling it, thus triggering the shellcode.

The goal of the shellcode is to extract the final executable file payload in memory and transfer execution to it. This payload is the final sample in the infection chain and is responsible for handling communication to and from the command and control (C2) server.

The final payload contains a large array of obfuscation techniques, including string encryption and junk functions, as well as modifying exception handling structures to place “try and except” clauses part way through assembly instructions. This effectively breaks the instructions when disassembling, as many disassemblers will take these structure values into consideration when parsing a binary file. This results in a mangled control flow graph and failed decompilation due to the modifications in the exception handling structures.

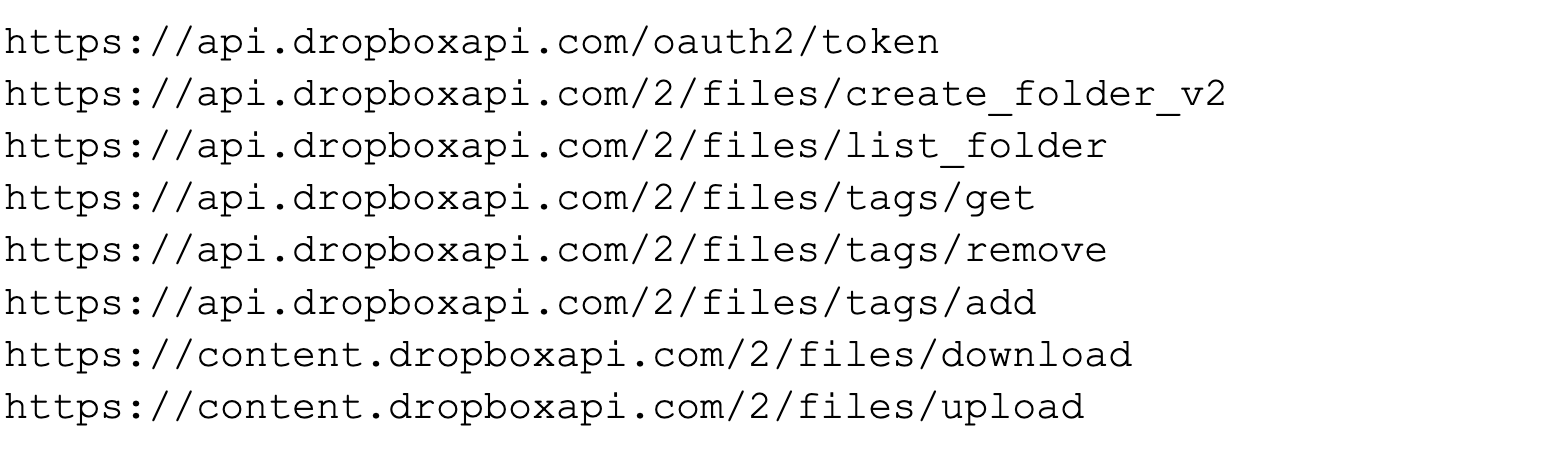

For communication, the payload uses both the Microsoft Graph and Dropbox API. Cloaked Ursa has previously leveraged Dropbox as a C2 server. However, Cloaked Ursa’s use of Microsoft Graph API to facilitate C2 communications appears to be a relatively new addition to their toolkit.

In addition to the string encrypted tokens and API keys required to communicate with these platforms, there is another string that stands out (shown in Figure 6), used when communicating with the Microsoft Graph API: Teams_test.

Given that the Graph API allows for interacting with a number of different Microsoft 365 Services including Microsoft Teams, it’s possible that this was an initial test for communicating via Teams or the Graph API.

If communication fails via the Graph API several times, communication via Dropbox is attempted. Several decrypted strings in the binary provide insight into the use of Dropbox for communication:

Previously, Cloaked Ursa-linked payloads that communicate with Dropbox had wrapped communications in a packet that resembled an MP3 file. The MP3 magic bytes (ID3\x04\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00#TSSE) were prepended to the encrypted data and uploaded to Dropbox as an MP3 file.

In this sample, it appears that they have opted to use BMP files. The threat actor-owned C2 will upload commands to Dropbox that are wrapped in the BMP format. These commands are retrieved by the payload and then parsed, decrypted and executed. Any data that the payload uploads to Dropbox will also be encrypted and wrapped in the BMP format.

In terms of handled commands, the payload accepts five possible requests from the C2 server, as described in the table below.

| Command Value | Command Description |

| 0 | Inject shellcode into explorer.exe or smartscreen.exe |

| 1 | Execute specified command with CMD.exe |

| 2 | Read from local file |

| 3 | Write data to local file |

| 4 | Spawn and inject code into WerFault.exe |

Table 2. Commands handled by sample.

Based on the lack of additional commands, it’s likely this is merely a loader for a further sample. As of mid-June, the Dropbox and Graph API credentials are no longer valid, preventing access to any information that was uploaded to either platform.

Technical Analysis of Turkey Campaign

We identified an additional sample with similar characteristics to other attributed Cloaked Ursa campaigns, which we believe to have been targeting the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We did not observe the lure or lures used in this campaign, but we are able to identify the attack chain after the original lure. We assess that the original lure enticed the target to click on hxxps:// simplesalsamix[.]com/e-yazi.html. The URL is no longer active, but it originally retrieved an HTTP smuggling file named e-yazi.html (SHA256: cd4956e4c1a3f7c8c008c4658bb9eba7169aa874c55c12fc748b0ccfe0f4a59a).

The downloaded file is assigned the name e-yazi.zip. (SHA256: 0dd55a234be8e3e07b0eb19f47abe594295889564ce6a9f6e8cc4d3997018839). This sample contains five files.

Once again, a legitimate WinWord.exe binary was found within the archive, named e-yazi.docx.exe. However, whitespace was added between the .docx and .exe, resulting in the file appearing as a document file.

Alongside the WinWord.exe, a file named APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64.dll (SHA256:

60d96d8d3a09f822ded0a3c84194a5d88ed62a979cbb6378545b45b04353bb37

) was present once again, as well as a file named okxi4t.z (SHA256: 03959c22265d0b85f6c94ee15ad878bb4f2956a2b0047733edbd8fdc86defc48). This file is similar to the previously mentioned ojg2.px in that it contains encrypted shellcode.

On execution of WinWord.exe, APPVISVSUBSYSTEMS64.dll is sideloaded and (assuming the standard anti-analysis checks were passed) it would open and read the data from okxi4t.z before decrypting it and injecting it into the first running process it can.

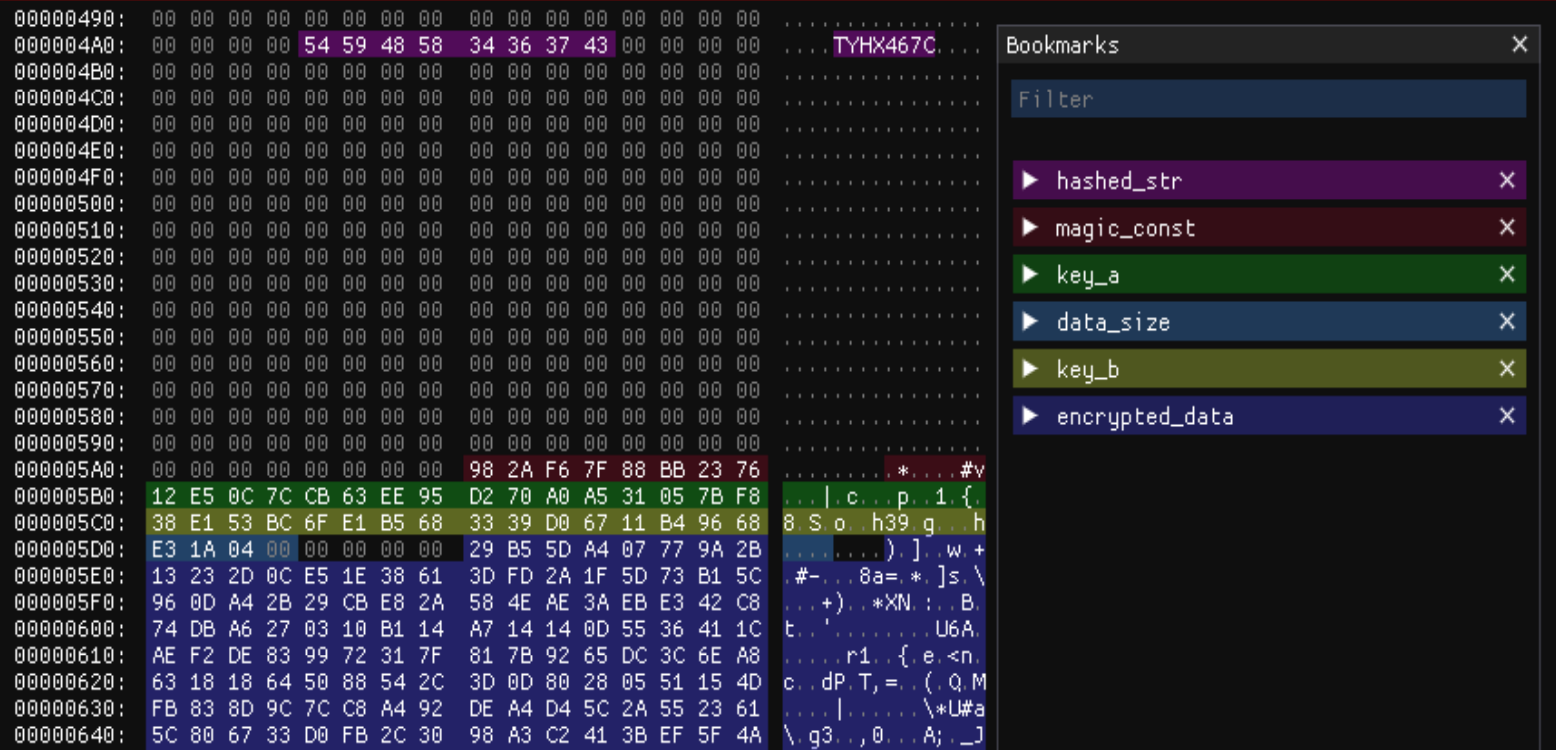

The injected shellcode shares a number of similarities with code seen in the BMW-related sample, such as the following:

- General execution flow

- Functionality to unhook numerous Windows API calls

- Its obfuscation techniques

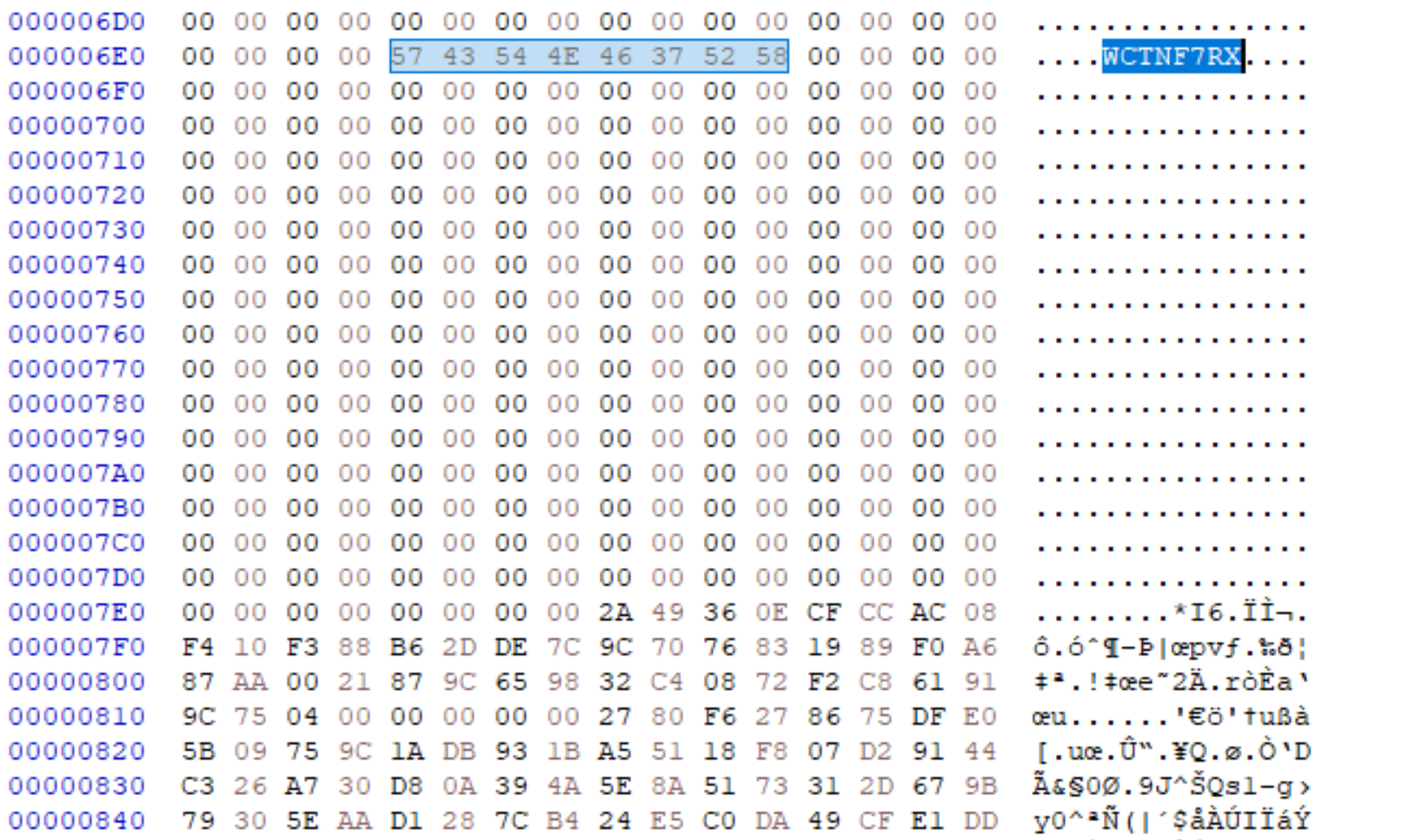

We were also able to confirm that the shellcode contained overlaps with the fourth-stage shellcode dropper loader, shown in Figure 7, as described in the Cloaked Ursa QUARTERRIG malware report by Military Counterintelligence Service and CERT.PL. The same algorithm and payload structure can be seen within the injected shellcode, as shown in Figure 8, aside from minor differences such as the values of the magic_const and hashed_str.

The final payload within this infection chain is somewhat similar to the BMW-linked final payload, in that it leverages both Microsoft Graph API and the Dropbox API for C2 communication. Instead of Teams_test being the project name, it’s set to mytestworkapp1. The hard-coded API tokens are also different from the initially analyzed sample.

Similar obfuscation was employed within this sample, including string encryption and control flow obfuscation via abusing the exception handling structures. However, there are no junk functions added to the sample, resulting in a much smaller file size of 498 KB.

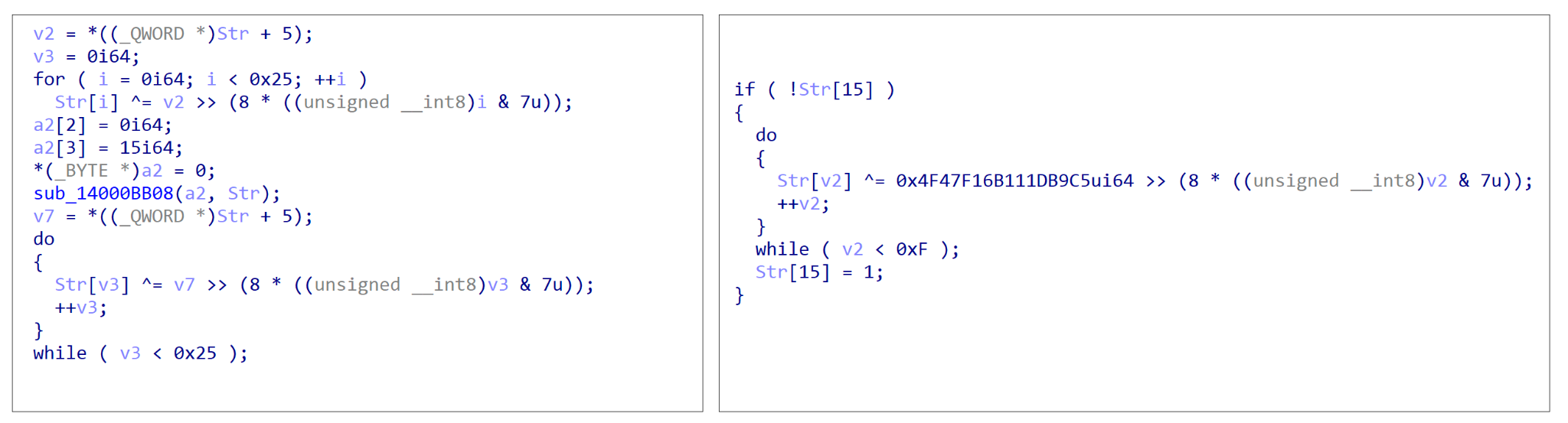

It’s worth noting that the string encryption algorithms appear to line up with those seen within the Cloaked Ursa SNOWYAMBER and QUARTERRIG malware reports by the Military Counterintelligence Service and CERT.PL. Many of the string decryption functions leverage inline assembly keys (as seen in Figure 9), while the rest retrieve keys from the .rdata directory.

It’s clear that Cloaked Ursa remains dedicated to identifying legitimate platforms to host their C2 servers, based on their usage of the Microsoft Graph API within these two samples, as well as past reports describing C2 communication via Notion and Google Drive.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh