To misquote William Gibson: “The past is still here with us, just unevenly distributed.” I have 2022-3-22 03:0:0 Author: www.tbray.org(查看原文) 阅读量:21 收藏

To misquote William Gibson: “The past is still here with us, just unevenly distributed.” I have a story to tell that stars Sergei Rachmaninoff and me. It starts just before 1900 in Moscow. My part ends around 1972 in the mountains of Lebanon, looking down over Beirut and the blue Mediterranean. It doesn’t have to do with computers and nothing in it matters to anyone living except me, but maybe you’ll enjoy a faintly exotic musical echo from a long time ago a long way away.

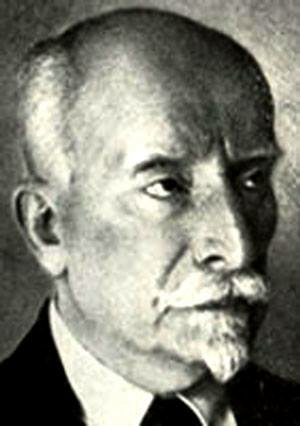

In 1900, Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943), pictured in 1897, was in rough shape. Which is surprising, given that in 1892 he’d graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the highest possible mark and a “Great Gold Medal”. He had a brief moment in the sun, enjoying a summer-of-1893 retreat in Kharkiv, a name much in the news as I write. But then in 1893 his hero Tchaikovsky died and then his First Symphony got brutal reviews, and a serious case of composer’s block silenced his musical output. Rachmaninoff was reduced to giving lessons to pay the rent.

Enter Dahl · Meet Nikolai Dahl (Николай Владимирович Даль) (1860-1939), a Russian Empire physician who studied psychology in France after graduating from Moscow University. A lover of music and competent violist, he was hired by Rachmaninoff in January 1900. Between then and April, a daily program of hypnosis and other supportive therapies had good effect, leading to the composition of the famous and much-played Piano Concerto #2, premiered in October 1901 and dedicated to Dahl.

Dahl had a son, also named Nikolai, whose life intersected mine.

But before we leap forward in time, let history record that Rachmaninoff’s story had a mostly happy ending, in that he kept on writing and playing music until his last days, seemed reasonably satisfied with life, and was never broke. Some regret that performing (he was a hell of a piano player) was more lucrative than composing and thus we are left with less of his music, which is almost all pretty great, than we might have wished.

Professor Dale · In 1962, when I was seven, my father graduated from Oregon State University with a Ph.D. in Agriculture and accepted a faculty appointment at the American University of Beirut (everyone says AUB).

At some point in my youth, music lessons were thought appropriate and I was asked which instrument. When I said “something that plays low notes” they decided that my hands were too small for double bass, so I took up cello. When I bothered to practice I made good progress.

Some years later my parents were looking for a new cello teacher, and someone suggested “Professor Dale”, who lived up in the mountains. Specifically in Brummana, a pleasant and verdant town overlooking Beirut from the slopes of Mount Lebanon. Its climate is pleasantly moderate in summer; that and the view have made it long-time escape for residents of hot climates around the Middle East.

So I became a student of Professor Dale — yes, the son of the physician who treated Rachmaninoff. I don’t know why or when his surname’s spelling changed. More on him later but first, the question of travel.

The road to Brummana · I was a sixteen-year-old kid in Beirut and needed to get a half-hour’s drive up the mountainside for my cello lesson. It was pretty easy, because of the service option. A service (a French word, rhymes with “bear lease”) is a taxi with a fixed route, either circular inside the city or back-and-forth between two points. You could hail them anywhere on their route, you’d be one of up to five passengers, and the price was the same no matter where you got off or on. And it was cheap.

At this point in time basically all the services were “Ponton” style Mercedes sedans with bench seats front and back; thus room for five paying customers.

Photo: Lothar Spurzem, CC BY-SA 2.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

Every town in Lebanon had a designated corner in Beirut where its services left from. Brummana’s was in the Burj, the old downtown that used to be a warren of fantastically picturesque souks (bazaars) full of gold and spices and colors and stories. That was until it was shelled flat during the Lebanese Civil War, I forget whether it was by the asshole Phalangists or the asshole Islamists, now it’s a totally boring mall. But I digress.

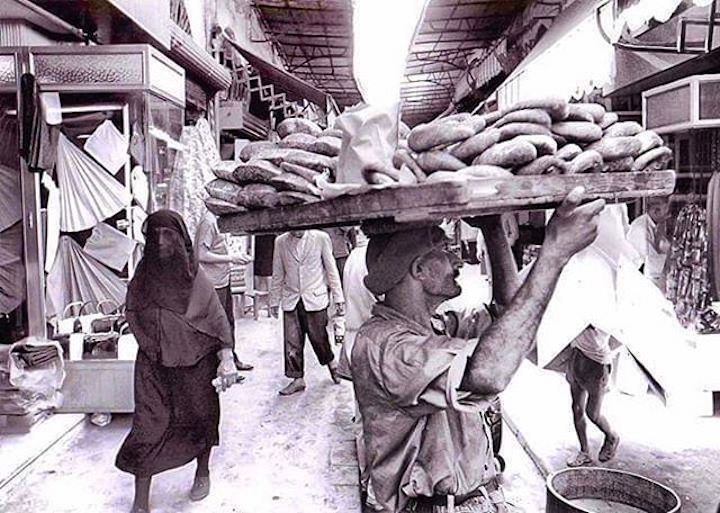

Souk Ayass in 1966. Photo: Mounir Diab, CC BY-SA 4.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

Anyhow, I’d take my cello downtown on the city bus (cost: pennies), stroll over to the Brummana corner, and catch the next service, they left all the time. My Arabic wasn’t great but plenty good enough to say the equivalent of “C’mon man don’t gimme that, I know the right price.” Nobody’s feelings were hurt, I was a blond foreigner and presumably clueless until I proved I wasn’t. The right price was something like the equivalent of $2 for a half-hour ride. Those Mercedes trunks were cavernous, there was always room for the cello. No driver ever seemed to find it weird when I asked him to pop the lid for the instrument.

I told the driver where in Brummana to pull over, the Professor’s place was only aa couple blocks from the highway, and after my lesson I’d stroll back up to the highway and flag a downhill service. At the time, it never struck me that any of this was exotic.

The Professor’s story · With Professor Dale (I never called him anything else) I spoke French; the natural second (perhaps first) language of a pre-Revolutionary Russian aristocrat. He told me that he’d been Second Cello in the Kyiv Opera before the revolution, then he’d had to run for his life. He ended up in Bombay, where there were no orchestra jobs, so he taught himself saxophone and worked in a nightclub playing jazz. “Mais je n'aime pas cette sensibilité musicale des N*, ni ces rythmes” he said — I’m pretty sure “N*” is That Word en français. I’m not going to defend his language, he was 80-ish in 1971 and it might not have occurred to him to deny racism.

I gather that after Bombay he lived in South America for a while; he showed me pictures of he and his wife, young and glamorous on horseback on the Pampas. He never said how he came to the mountains of Lebanon but later I found out; his father, Rachmaninoff’s guy, had settled in Beirut in 1925 and died there in 1939. He played viola in the AUB orchestra, an ensemble in which I briefly played cello; there’s another connection.

Professor Dale loved to ramble on about music; I remember few of the stories. But I remember his repeated criticism of my fingering, his explanation that in the German style, the fingers of the left hand hit the strings like little hammers, while in the French style, they caress them like lovers. And the French style was really much to be preferred. Couldn’t and can’t disagree but to this day I hit the strings a little hard.

Manuscript and Ruth · One time the Professor had a favor to ask. He had a Rachmaninoff manuscript score (I forget of what), and he understood that my father was a Professor and that at the University there would be these new-fangled “Xerox machines”; could I get him a copy? My family was terribly impressed. It never dawned on me to keep one for myself.

It turns out that as I write this there’s a living link to Rachmaninoff. Pianist Ruth Slenczynska, now 97, studied with him, and has just released a new album, featuring Rachmaninoff of course.

Ruth Slenczynska in 1957. Photo: James J. Kriegsmann,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

You can watch a concert she gave just last month and if you do, your mind is connecting through just one other’s to the nineteenth century.

Later on · A colleague of my Dad’s in the faculty of Agriculture had a daughter who also became a student of Professor Dale and was happy to drive us up to Brummana once a week, so I didn’t have to take the service any more. Professor Dale’s wife (always and only “Madame”) was very happy to entertain the Agriculture prof and the student not being taught on the porch swing, serving tea and gateaux while we took in the lavish view down over the pine forests to the jewel-blue sea. Then Professor Dale would join us for more tea and company.

The cello is still in my living room. It is of Czech manufacture, dating from between the wars, so nearing its hundredth year. It sounds fine when I play it, which is rarely; these days I engage in West-African and Afro-Cuban percussion once or twice a week.

I’m going to close with a couple of pictures my Dad took. This is an impromptu quartet that happened one time on the back porch of our family’s temporary residence at the Faculty of Agriculture’s experimental farm, out in the Beka’a valley, not far from the Syrian border.

It’s a historical curiosity, not really much of a picture. But Dad was a good photographer and that day he also got this.

Thank you for listening.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh