2021-06-27 09:00:00 Author: arthurchiao.github.io(查看原文) 阅读量:180 收藏

Published at 2021-06-27 | Last Update 2021-06-27

TL; DR

- Some beginner-level BPF programs

- A containerized playground to exercise step by step

- tc/kernel code analysis to explain how things work in the underlying

- TL; DR

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Drop specific traffic with BPF: coding & testing

- 3 How does it work in the underlying? Dig inside

- 4 XDP version

- 5 Conclusion

- References

The superpower of being able to dynamically program the datapath of Linux kernel makes BPF/XDP an excellent tool for implementing efficient L3-L7 firewalls.

While it has already been used this way in production at large scale [2] - which indicates the maturity of technology - it’s still not clear to many network engineers and developers that how does this facility actually works in the underlying.

This post hopes to fill the gap by providing some simple but practical examples, and a containerized environment to carry out the experiments step by step.

1.1 BPF/XDP in a nutshell

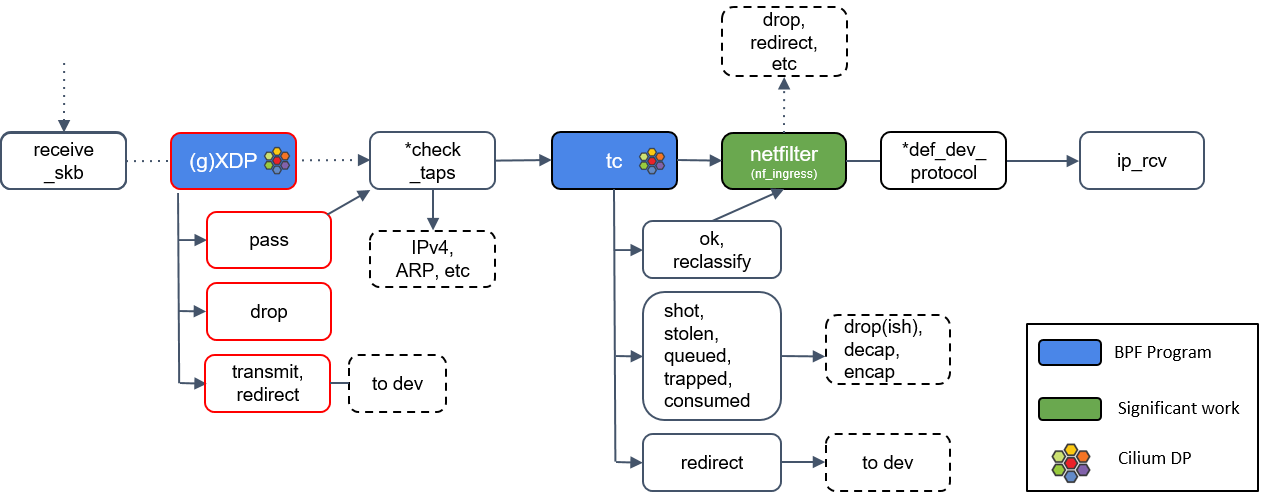

This post aims to be a practical guide, so we try to explain how BPF/XDP works with the simplest words. As shown below, kernel embeds some hooking points in its network processing path. Each hooking point can be viewed as a sandbox,

Fig 1. Network processing path and BPF hooking points

-

By default, no code in the sandboxs, it’s empty. Kernel processing steps in this case:

- Processing stage 1

- Sandbox processing: do nothing (allow any, effectively)

- Processing stage 2

-

When users inject their code into the sandboxs, the overall processing logic will be changed. Logic now:

- Processing stage 1

- Sandbox processing: executing user code (may modify the input packets), returning a verdict to the kernel, indicating how to process the packet in the next (e.g. drop/continue/redirect)

- Doing something according to the verdict returned by step 2

1.2 Environment info

Basic info:

- Ubuntu:

20.04 - Docker:

19.03.13 - Clang:

10.0.0-4ubuntu1 - tc (iproute2):

tc utility, iproute2-ss200127

arping

(node) $ sudo apt install -y arping

nsenter-ctn

This is a a wrapper around nsenter, which

executes commands in the specified container's namespace</code>:

# Example: nsenter-ctn <ctn-id> -n ip addr show eth0

function nsenter-ctn () {

CTN=$1 # Container ID or name

PID=$(sudo docker inspect --format "{{.State.Pid}}" $CTN)

shift 1 # Remove the first arguement, shift remaining ones to the left

sudo nsenter -t $PID $@

}

Put it into your ~/.bashrc then

(node) $ source ~/.bashrc

1.3 Playground setup

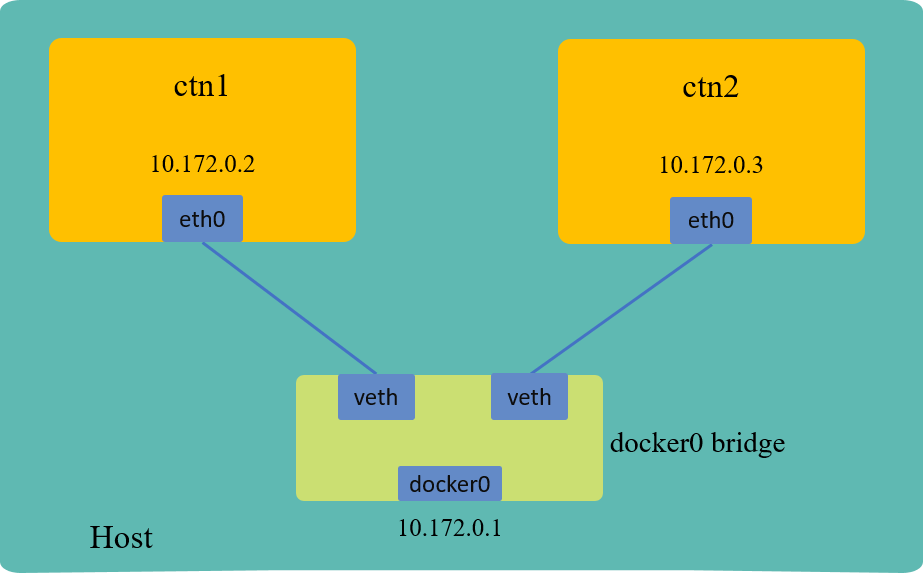

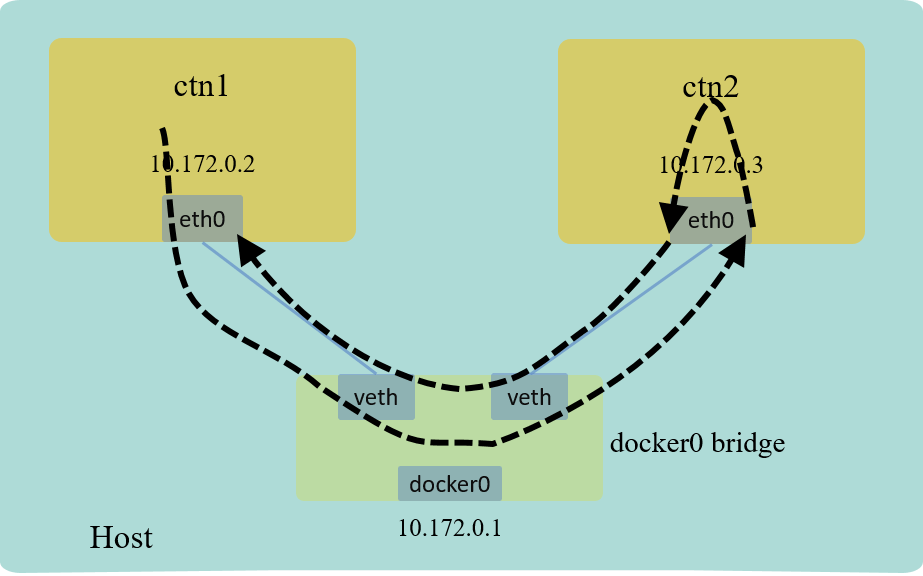

For ease of exercising, we’ll setup a containerized environment. Creating two containers, one used as client and the other as server, topology shown as below:

Fig 2. Playground used in this post

With default configurations, each container will get an IP address from docker, and be connected to the default Linux bridge

docker0.

Commands:

# Create client container

(node) $ sudo docker run --name ctn1 -d alpine:3.12.0 sleep 30d

# Create server container: listen at 0.0.0.0:80 inside the container, serving HTTP

(node) $ sudo docker run --name ctn2 -d alpine:3.12.0 \

sh -c 'while true; do echo -e "HTTP/1.0 200 OK\r\n\r\nWelcome" | nc -l -p 80; done'

Check the ip addresses of the containers:

# nsenter-ctn <container ID/Name> -n <command>

# -n: enter the network namespace of the container

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n ip a

68: eth0@if69: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

inet 172.17.0.2/16 brd 172.17.255.255 scope global eth0

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n ip a

70: eth0@if71: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

inet 172.17.0.3/16 brd 172.17.255.255 scope global eth0

1.4 Connectivity test

Now verify that client can reach the server, with connectivity test tools working at different network layers:

Fig 3. Connectivity test

L2 test with arping (ARP)

arping server IP from client:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n arping 172.17.0.3

Unicast reply from 172.17.0.3 [02:42:ac:11:00:03] 0.009ms

Unicast reply from 172.17.0.3 [02:42:ac:11:00:03] 0.015ms

^CSent 2 probe(s) (1 broadcast(s))

L2 connectivity OK!

And we can also capture the traffic inside ctn2:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tcpdump -i eth0 arp

15:23:52.634753 ARP, Request who-has 172.17.0.3 (Broadcast) tell 172.17.0.2, length 28

15:23:52.634768 ARP, Reply 172.17.0.3 is-at 02:42:ac:11:00:03 (oui Unknown), length 28

...

L3 test with ping (ICMP)

Similar as the L2 test, but with the ping command:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n ping 172.17.0.3 -c 2

64 bytes from 172.17.0.3: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.064 ms

64 bytes from 172.17.0.3: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.075 ms

L3 connectivity OK!

L4/L7 test with curl (TCP/HTTP)

Fire a HTTP GET request with the curl command:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n curl 172.17.0.3:80

Welcome

L4/L7 connectivity OK!

The captured traffic inside ctn2:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tcpdump -nn -i eth0

15:44:10.192949 IP 172.17.0.2.52748 > 172.17.0.3.80: Flags [S], seq 294912250

15:44:10.192973 IP 172.17.0.3.80 > 172.17.0.2.52748: Flags [S.], seq 375518890, ack 294912251

15:44:10.192987 IP 172.17.0.2.52748 > 172.17.0.3.80: Flags [.], ack 1, win 502

15:44:10.193029 IP 172.17.0.2.52748 > 172.17.0.3.80: Flags [P.], seq 1:75, ack 1: HTTP: GET / HTTP/1.1

15:44:10.193032 IP 172.17.0.3.80 > 172.17.0.2.52748: Flags [.], ack 75, win 509

15:44:10.193062 IP 172.17.0.3.80 > 172.17.0.2.52748: Flags [P.], seq 1:28, ack 75: HTTP: HTTP/1.0 200 OK

...

Now let’s write some simple BPF programs.

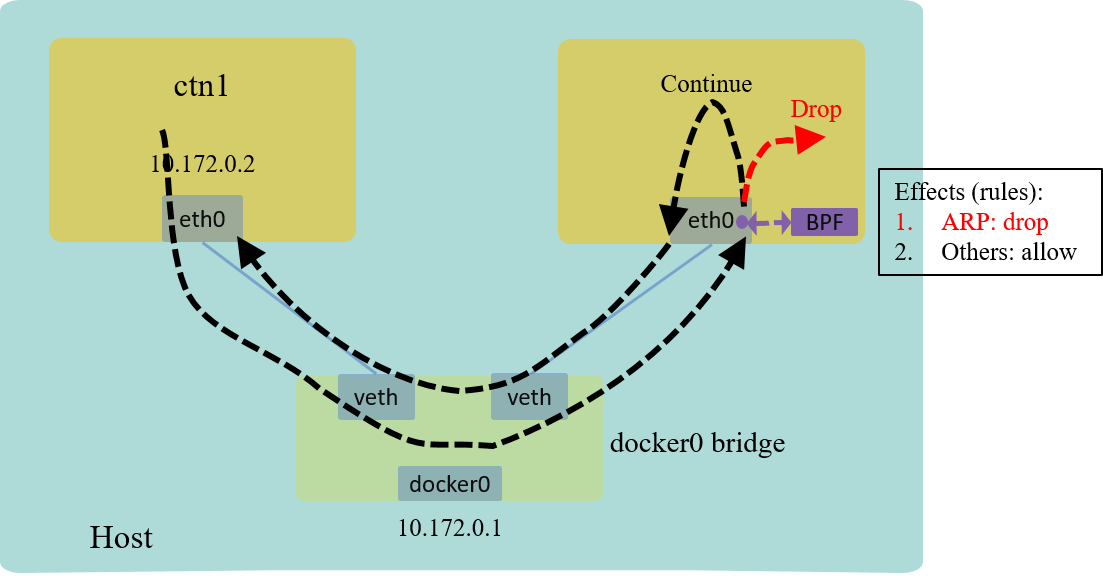

2.1 L2 example: drop all ARP packets

Source code: drop-arp.c

As the following snippet shows, this example turns out to be extreamly simple, consisting of only 10+ lines of C code:

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <linux/pkt_cls.h>

#include <linux/if_ether.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

__attribute__((section("ingress"), used))

int drop(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

void *data = (void*)(long)skb->data;

void *data_end = (void*)(long)skb->data_end;

if (data_end < data + ETH_HLEN)

return TC_ACT_OK; // Not our packet, return it back to kernel

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

if (eth->h_proto != htons(ETH_P_ARP))

return TC_ACT_OK;

return TC_ACT_SHOT;

}

Some explanations:

- Specify a section name (

section("ingress")) for the program, which will be used in later’s loading process; - For each packet (

skb), locate the memory address that holds the starting address of the ethernet header; - Retrieve the next-proto-info in ether header,

- if

h_proto == ARP, return a flag (TC_ACT_SHOT) dictating the kernel to drop this packet, - otherwise, return a

TC_ACT_OKflag indicating the kernel to continue its subsequent processing.

- if

The above code will act as a "filter" to filter the given traffic/packets, let’s see how to use it.

Compile, load, and attach to kernel hooking point

The following commands compile the C code into BPF code, then load it into

the ingress hook of ctn2’s eth0 interface:

# Compile to BPF code

(node) $ clang -O2 -Wall -target bpf -c drop-arp.c -o drop-arp.o

# Add a tc classifier

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tc qdisc add dev eth0 clsact

# Load and attach program (read program from drop-arp.o's "ingress" section) to eth0's ingress hook

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tc filter add dev eth0 ingress bpf da obj drop-arp.o sec ingress

# Check the filter we've added just now

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tc filter show dev eth0 ingress

filter protocol all pref 49152 bpf chain 0

filter protocol all pref 49152 bpf chain 0 handle 0x1 drop-arp.o:[ingress] direct-action not_in_hw id 231 tag c7401029d3d4561c jited

Effectively, this will filter all the inbound/ingress traffic to ctn2.

Refer to other posts in this site about how tc classifier (

clsact) works.

Test

Now repeat our L2 connectivity test:

(ctn1) / # arping 172.17.0.3

ARPING 172.17.0.3 from 172.17.0.2 eth0

^CSent 4 probe(s) (4 broadcast(s))

It becomes unreachable!

The captured traffic inside ctn2:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tcpdump -i eth0 arp

16:02:03.085028 ARP, Request who-has 172.17.0.3 (Broadcast) tell 172.17.0.2, length 28

16:02:04.105954 ARP, Request who-has 172.17.0.3 (Broadcast) tell 172.17.0.2, length 28

...

But ping (ICMP) and curl (HTTP/TCP) still OK:

/ # ping 172.17.0.3

PING 172.17.0.3 (172.17.0.3): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 172.17.0.3: seq=0 ttl=64 time=0.068 ms

64 bytes from 172.17.0.3: seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.070 ms

^C

Note: ARP entry to ctn2 should exist before this testing (not be GC-ed), otherwise ping and curl will also fail, as L3-L7 communications also rely on the MAC address in the ARP entry.

$ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n arp -n Address HWtype HWaddress Flags Mask Iface 172.17.0.3 ether 02:42:ac:11:00:03 C eth0

Explanation

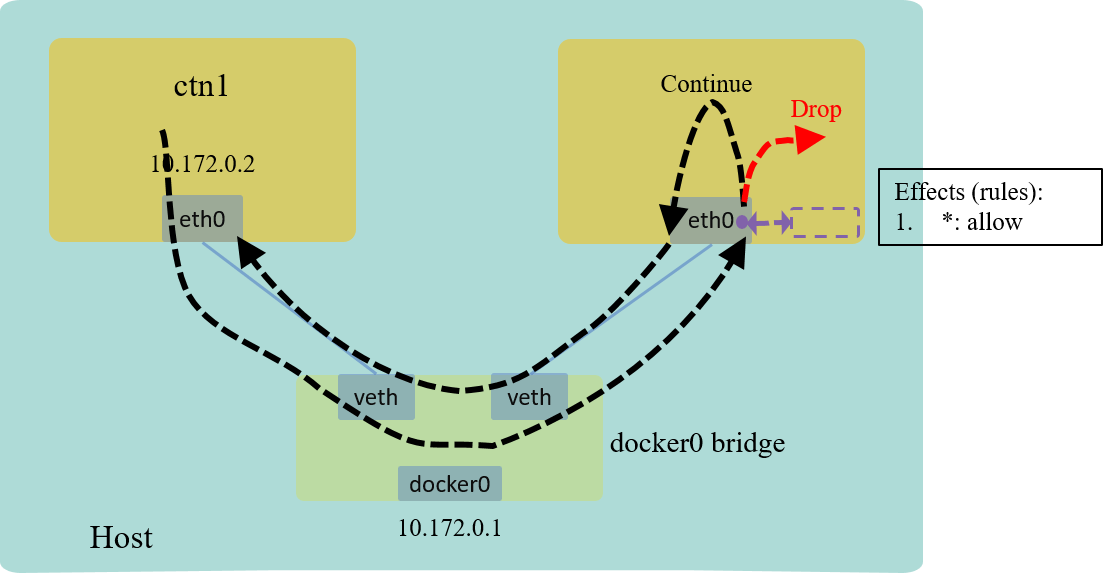

With the above code and with our testing, we’ve got a simple firewall to drop all ARP packets for ctn2’s ingress traffic. This is realized by loading our BPF program to the ingress hook of the network interface:

Fig 4. L2 example: drop all ARP traffic

Cleanup

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tc qdisc del dev eth0 clsact 2>&1 >/dev/null

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tc filter show dev eth0 ingress

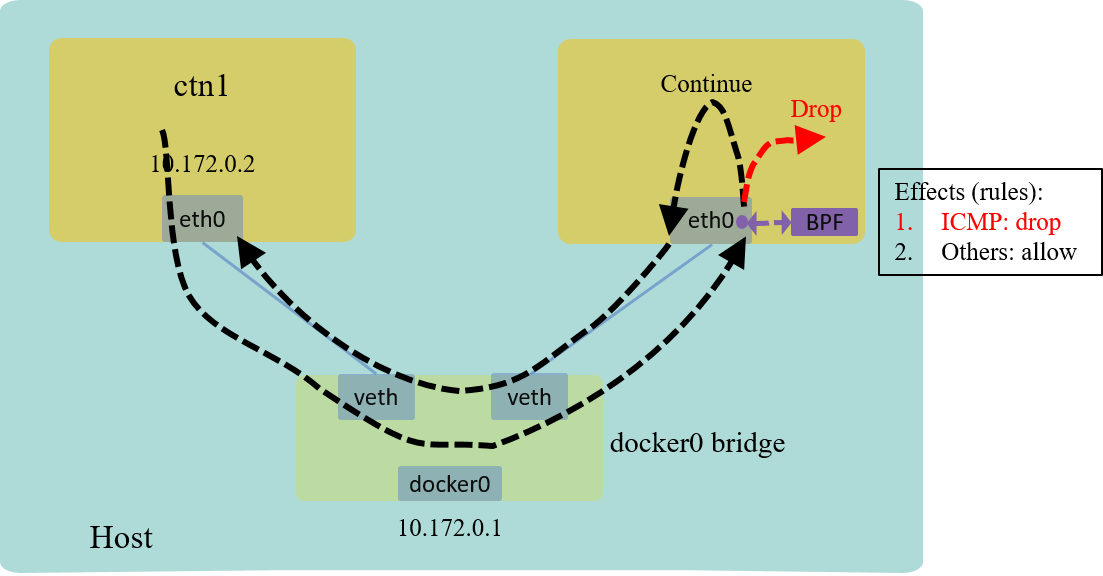

2.2 L3 example: drop all ICMP packets

Source code: drop-icmp.c

This example is quite similar with the previous one, except that we need to parse to IP header:

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <linux/pkt_cls.h>

#include <linux/if_ether.h>

#include <linux/ip.h>

#include <linux/tcp.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

__attribute__((section("ingress"), used))

int drop(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

const int l3_off = ETH_HLEN; // IP header offset

const int l4_off = l3_off + sizeof(struct iphdr); // L4 header offset

void *data = (void*)(long)skb->data;

void *data_end = (void*)(long)skb->data_end;

if (data_end < data + l4_off)

return TC_ACT_OK;

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

if (eth->h_proto != htons(ETH_P_IP))

return TC_ACT_OK;

struct iphdr *ip = (struct iphdr *)(data + l3_off);

if (ip->protocol != IPPROTO_ICMP)

return TC_ACT_OK;

return TC_ACT_SHOT;

}

Compile, load, and attach to kernel hooking point

Compile and load the program with the same commands in the previous example.

Test

Test with the same commands as in the previous section.

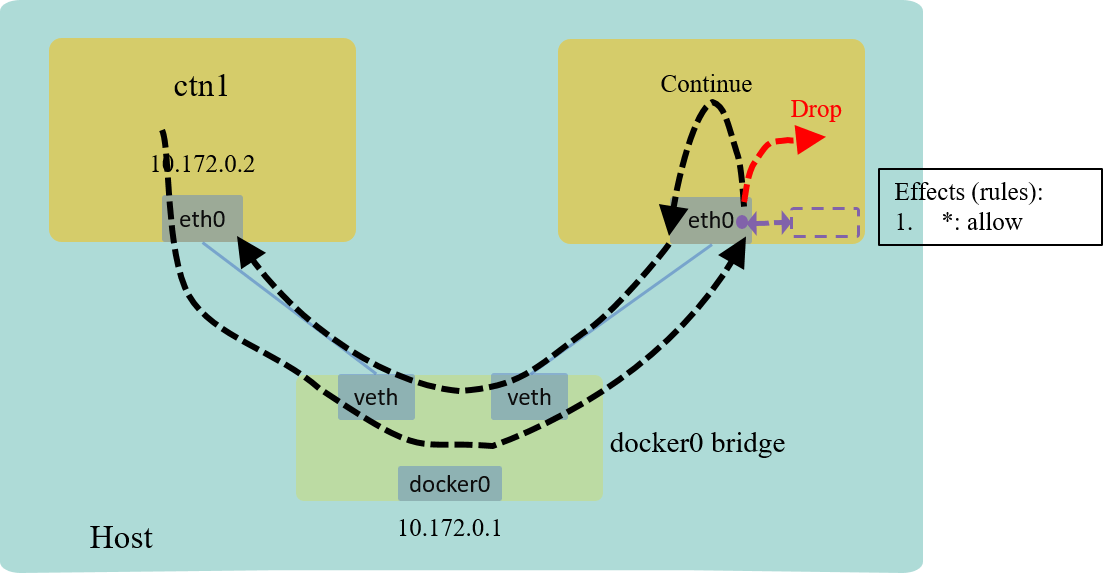

Explanation

The effect looks like below:

Fig 5. L3 example: drop all ICMP traffic

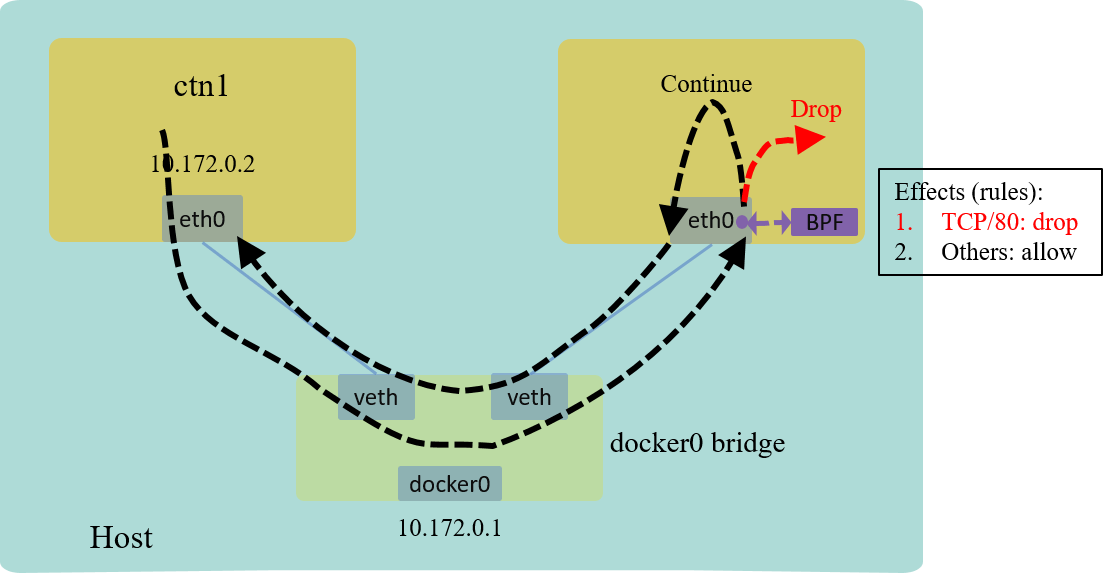

2.3 L4 example: drop TCP/80 packets only

Code: drop-tcp.c

Again, this example is quite similar with the previous ones, except that we need to parse to TCP header to get the destination port information.

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <linux/pkt_cls.h>

#include <linux/if_ether.h>

#include <linux/ip.h>

#include <linux/tcp.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

__attribute__((section("ingress"), used))

int drop(struct __sk_buff *skb) {

const int l3_off = ETH_HLEN; // IP header offset

const int l4_off = l3_off + sizeof(struct iphdr); // TCP header offset

const int l7_off = l4_off + sizeof(struct tcphdr); // L7 (e.g. HTTP) header offset

void *data = (void*)(long)skb->data;

void *data_end = (void*)(long)skb->data_end;

if (data_end < data + l7_off)

return TC_ACT_OK; // Not our packet, handover to kernel

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

if (eth->h_proto != htons(ETH_P_IP))

return TC_ACT_OK; // Not an IPv4 packet, handover to kernel

struct iphdr *ip = (struct iphdr *)(data + l3_off);

if (ip->protocol != IPPROTO_TCP)

return TC_ACT_OK;

struct tcphdr *tcp = (struct tcphdr *)(data + l4_off);

if (ntohs(tcp->dest) != 80)

return TC_ACT_OK;

return TC_ACT_SHOT;

}

Test: TCP/80 traffic being dropped

curl from client container, we’ll find that it hangs there:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n curl 172.17.0.3:80

^C

Check the traffic inside ctn2:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn2 -n tcpdump -nn -i eth0

16:23:48.077262 IP 172.17.0.2.52780 > 172.17.0.3.80: Flags [S], seq 2820055365, win 64240, options [mss 1460,sackOK,TS val 3662821781 ecr 0,nop,wscale 7], length 0

16:23:49.101081 IP 172.17.0.2.52780 > 172.17.0.3.80: Flags [S], seq 2820055365, win 64240, options [mss 1460,sackOK,TS val 3662822805 ecr 0,nop,wscale 7], length 0

16:23:51.143643 IP 172.17.0.2.52780 > 172.17.0.3.80: Flags [S], seq 2820055365, win 64240, options [mss 1460,sackOK,TS val 3662824847 ecr 0,nop,wscale 7], length 0

^C

As shown above, the TCP packets got dropped: client retransmitted many times, until timed out.

Test: TCP/8080 traffic not dropped

Now let’s start another HTTP server inside ctn2, to verify that HTTP traffic at other TCP ports is still ok.

# Start another server, listen at :8080

(node) $ sudo docker exec -it ctn2 sh

/ # while true; do echo -e "HTTP/1.0 200 OK\r\n\r\nWelcome" | nc -l -p 8080; done

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: 172.17.0.3:8080

User-Agent: curl/7.68.0

Accept: */*

Now curl the new service from client:

(node) $ nsenter-ctn ctn1 -n curl 172.17.0.3:8080

Welcome

Successful!

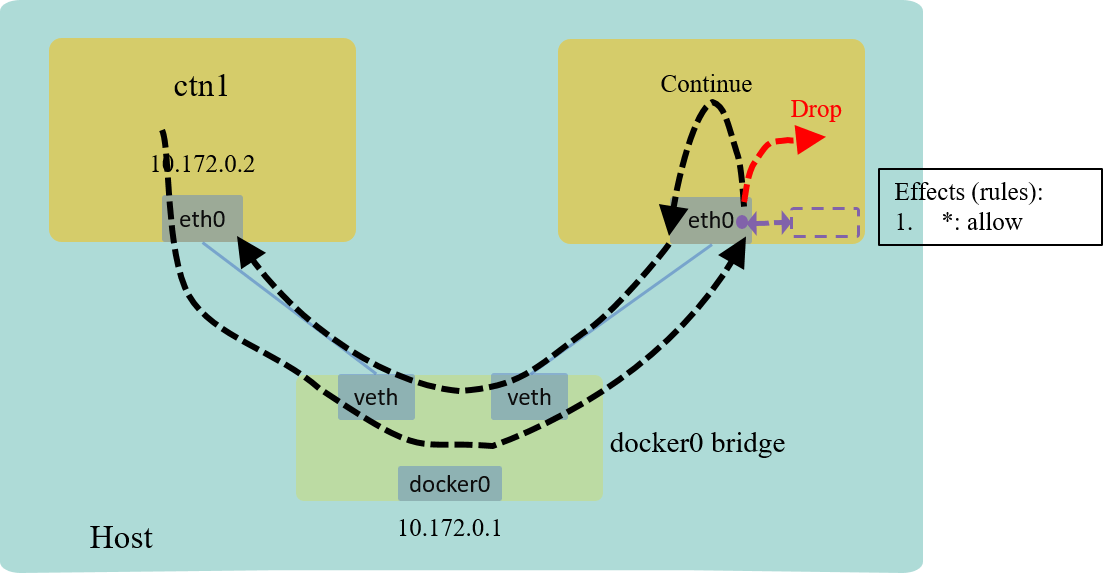

Explanation

The effect:

Fig 6. L4/L7 example: drop all TCP/80 traffic

2.4 Tear down playground

(node) sudo docker rm -f ctn1 ctn2

2.5 Summary

In the above, we showed three toy examples to drop specific traffic. These programs are not that useful til now, but, by combining the following filtering and hooking stuffs, they could evolve to a real firewalling program.

Filtering more fields

For real firewalling purposes, we should perform the filtering with more conditions, such as:

- Source and/or destination MAC addresses

- Source and/or destination IP addresses

- Source and/or destination TCP ports

- Or even L7 conditions, such as method (

GET/POST/DELETE), routes (/api/public,/api/private)

All these information are accessible (from skb) in BPF programs’s context.

Hooking at more places

We could attach BPF programs at other hooking points, not just the ingress one.

Beside, we could also attach programs at other network devices, for example,

at the corresponding vethxx devices of ctn2, which will achieve the exactly

same effects. Actually this is how Cilium does in it’s default datapath mode

(veth pair mode) [1].

Making filtering conditions configurable

This can be achieved with BPF maps, but that’s out of the scope of this post.

Previous sections demonstrate that our BPF code works. But how does that work in the underlying? This section digs into the hidden part, specifically, we’ll see:

- How does the BPF code get injected into the kernel hooking point, and

- Where exactly does the BPF code get triggered for execution.

3.1 Loading BPF into kernel part 1: tc front end processing

Loading BPF code into kernel further splits into two part:

- TC frontend (userspace): convert user commands into a netlink message and send it to kernel

- BPF backend (kernel space): process the netlink request, finish the loading/attaching job

This section explores the first part.

Source code

tc code is included in the iproute2 package:

$ git clone https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/network/iproute2/iproute2.git

$ cd iproute2

Calling stack

Take the following command as example,

$ tc filter add dev eth0 ingress bpf da obj drop-arp.o sec ingress

Below is the calling stack:

// Calling stack of parsing and executing the following tc command:

// $ tc filter add dev eth0 ingress bpf da obj drop-arp.o sec ingress

main // tc/tc.c

|-do_cmd // tc/tc.c

|-if match(*argv, "filter")

return do_filter // tc/filter.c

/

/--/

/

do_filter // tc/filter.c

|-if match(*argv, "add")

return tc_filter_modify // tc/filter.c

/

/--/

/

tc_filter_modify // tc/filter.c

|-struct {

| struct nlmsghdr n; // netlink message header

| struct tcmsg t; // tc message header

| char buf[];

|} req = {

| n.nl.msg_type = "add",

| }

|

|-Parse CLI parameters: "dev eth0 ingress"

|

|-q->parse_fopt "bpf da obj drop-arp.o sec ingress"

| |-bpf_parse_opt // tc/f_bpf.c

|

|-rtnl_talk // lib/libnetlink.c

|-__rtnl_talk // lib/libnetlink.c

|-__rtnl_talk_iov // lib/libnetlink.c

|-sendmsg

Explanations

The above frontend processing logic explains itself clearly:

- Parse CLI parameters from user inputs (

tccommands) - Init a netlink message with those parameters

- Send the netlink message to kernel

On receiving the message, kernel will do the subsequent things for use - we’ll see in the next section.

Netlink is used to transfer information between the kernel and user-space processes. It consists of a standard sockets-based interface for user space processes and an internal kernel API for kernel modules.

Netlink is not a reliable protocol. It tries its best to deliver a message to its destination(s), but may drop messages when an out-of-memory condition or other error occurs [3].

See datapath: Set timeout for default netlink socket for an example on how netlink message loss leads to problems.

3.2 Loading BPF into kernel part 2: kernel backend processing

Netlink message handlers registration

During kernel initialization, the net subsystem will register many callbacks, which will be called when certain events received, such as

- tc qdiscs themselves

- tc qdisc

add/del/getevent callbacks - tc filter

add/del/getevent callbacks

as shown below:

// net/sched/sch_api.c

static int __init pktsched_init(void)

{

register_pernet_subsys(&psched_net_ops);

register_qdisc(&pfifo_fast_ops);

register_qdisc(&pfifo_qdisc_ops);

register_qdisc(&bfifo_qdisc_ops);

register_qdisc(&pfifo_head_drop_qdisc_ops);

register_qdisc(&mq_qdisc_ops);

register_qdisc(&noqueue_qdisc_ops);

// tc qdisc add/del/get callbacks

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_NEWQDISC, tc_modify_qdisc, NULL, 0);

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_DELQDISC, tc_get_qdisc, NULL, 0);

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_GETQDISC, tc_get_qdisc, tc_dump_qdisc, 0);

// tc filter add/del/get callbacks

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_NEWTCLASS, tc_ctl_tclass, NULL, 0);

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_DELTCLASS, tc_ctl_tclass, NULL, 0);

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_GETTCLASS, tc_ctl_tclass, tc_dump_tclass, 0);

}

Trigger tc_ctl_tclass() on receiving “tc filter add” messages

On receiving the "add filter" netlink message sent by tc, handler

tc_ctl_tclass() will be called:

// net/sched/sch_api.c

static int tc_ctl_tclass(struct sk_buff *skb, struct nlmsghdr *n, struct netlink_ext_ack *extack)

{

nlmsg_parse(n, sizeof(*tcm), tca, TCA_MAX, rtm_tca_policy, extack);

dev = __dev_get_by_index(net, tcm->tcm_ifindex);

// Step 1. Determine qdisc handle X:0

portid = tcm->tcm_parent;

clid = tcm->tcm_handle;

qid = TC_H_MAJ(clid);

// Step 2. Locate qdisc

q = qdisc_lookup(dev, qid);

// Step 3. Insert BPF code into hook

new_cl = cl;

cops->change(q, clid, portid, tca, &new_cl, extack); // -> cls_bpf_change()

tclass_notify(net, skb, n, q, new_cl, RTM_NEWTCLASS);

/* We just create a new class, need to do reverse binding. */

if (cl != new_cl)

tc_bind_tclass(q, portid, clid, new_cl);

out:

return err;

}

It parses tc parameters from netlink message, then call cops->change()

method to inject the specified BPF code into the correct hooking point.

Here, the change() method points to cls_bpf_change():

// net/sched/cls_bpf.c

static int cls_bpf_change(struct net *net, struct sk_buff *in_skb,

struct tcf_proto *tp, unsigned long base,

u32 handle, struct nlattr **tca, void **arg, bool ovr, struct netlink_ext_ack *extack)

{

struct cls_bpf_head *head = rtnl_dereference(tp->root);

struct cls_bpf_prog *oldprog = *arg;

struct nlattr *tb[TCA_BPF_MAX + 1];

struct cls_bpf_prog *prog;

nla_parse_nested(tb, TCA_BPF_MAX, tca[TCA_OPTIONS], bpf_policy, NULL);

prog = kzalloc(sizeof(*prog), GFP_KERNEL);

tcf_exts_init(&prog->exts, TCA_BPF_ACT, TCA_BPF_POLICE);

if (handle == 0) {

handle = 1;

idr_alloc_u32(&head->handle_idr, prog, &handle, INT_MAX, GFP_KERNEL);

} else if (!oldprog) {

idr_alloc_u32(&head->handle_idr, prog, &handle, handle, GFP_KERNEL);

}

prog->handle = handle;

cls_bpf_set_parms(net, tp, prog, base, tb, tca[TCA_RATE], ovr, extack);

cls_bpf_offload(tp, prog, oldprog, extack);

if (!tc_in_hw(prog->gen_flags))

prog->gen_flags |= TCA_CLS_FLAGS_NOT_IN_HW;

if (oldprog) {

idr_replace(&head->handle_idr, prog, handle);

list_replace_rcu(&oldprog->link, &prog->link);

tcf_unbind_filter(tp, &oldprog->res);

tcf_exts_get_net(&oldprog->exts);

tcf_queue_work(&oldprog->rwork, cls_bpf_delete_prog_work);

} else {

list_add_rcu(&prog->link, &head->plist);

}

*arg = prog;

return 0;

errout:

tcf_exts_destroy(&prog->exts);

kfree(prog);

return ret;

}

For our case here, cls_bpf_change()’s logic:

- Allocate memory for the BPF program,

- Append the program to the handler list at the corresponding hook with

list_add_rcu().

3.3 Kernel datapath: inbound handling entrypoint __netif_receive_skb_core()

BPF classifier callbacks registration

clsact is a TC classifier, again, it registers its handlers during module init:

// net/sched/cls_bpf.c

static struct tcf_proto_ops cls_bpf_ops __read_mostly = {

.kind = "bpf",

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.classify = cls_bpf_classify,

.init = cls_bpf_init,

.destroy = cls_bpf_destroy,

.get = cls_bpf_get,

.change = cls_bpf_change,

.delete = cls_bpf_delete,

.walk = cls_bpf_walk,

.reoffload = cls_bpf_reoffload,

.dump = cls_bpf_dump,

.bind_class = cls_bpf_bind_class,

};

static int __init cls_bpf_init_mod(void)

{

return register_tcf_proto_ops(&cls_bpf_ops);

}

module_init(cls_bpf_init_mod);

Calling into tc filtering framework

When kernel processing an ingress packet, it will come to the __netif_receive_skb_core()

method, then the call stack:

__netif_receive_skb_core

|-sch_handle_ingress

|-tcf_classify

|-tp->classify

|-cls_bpf_classify

|-BPF_PROG_RUN

|-// our bpf code

The method itself:

// net/dev/core.c

static int __netif_receive_skb_core(struct sk_buff *skb, bool pfmemalloc,

struct packet_type **ppt_prev)

{

trace_netif_receive_skb(skb);

if (skb_skip_tc_classify(skb))

goto skip_classify;

list_for_each_entry_rcu(ptype, &ptype_all, list) {

if (pt_prev)

ret = deliver_skb(skb, pt_prev, orig_dev);

pt_prev = ptype;

}

list_for_each_entry_rcu(ptype, &skb->dev->ptype_all, list) {

if (pt_prev)

ret = deliver_skb(skb, pt_prev, orig_dev);

pt_prev = ptype;

}

#ifdef CONFIG_NET_INGRESS

if (static_branch_unlikely(&ingress_needed_key)) {

skb = sch_handle_ingress(skb, &pt_prev, &ret, orig_dev);

if (!skb)

goto out;

if (nf_ingress(skb, &pt_prev, &ret, orig_dev) < 0)

goto out;

}

#endif

skb_reset_tc(skb);

skip_classify:

...

drop:

out:

return ret;

}

static inline struct sk_buff *

sch_handle_ingress(struct sk_buff *skb, struct packet_type **pt_prev, int *ret,

struct net_device *orig_dev)

{

#ifdef CONFIG_NET_CLS_ACT

struct mini_Qdisc *miniq = rcu_dereference_bh(skb->dev->miniq_ingress);

skb->tc_at_ingress = 1;

switch (tcf_classify(skb, miniq->filter_list, &cl_res, false)) {

case TC_ACT_OK:

case TC_ACT_RECLASSIFY:

...

default:

break;

}

#endif /* CONFIG_NET_CLS_ACT */

return skb;

}

// net/sched/sch_api.c

/* Main classifier routine: scans classifier chain attached

* to this qdisc, (optionally) tests for protocol and asks specific classifiers. */

int tcf_classify(struct sk_buff *skb, const struct tcf_proto *tp, struct tcf_result *res, bool compat_mode)

{

for (; tp; tp = rcu_dereference_bh(tp->next)) {

err = tp->classify(skb, tp, res);

if (err >= 0)

return err;

}

return TC_ACT_UNSPEC; /* signal: continue lookup */

}

Executing our BPF code

Finally, for our case, tp->classify is initialized as cls_bpf_classify:

// net/sched/cls_bpf.c

static int cls_bpf_classify(struct sk_buff *skb, const struct tcf_proto *tp,

struct tcf_result *res)

{

struct cls_bpf_head *head = rcu_dereference_bh(tp->root);

bool at_ingress = skb_at_tc_ingress(skb);

struct cls_bpf_prog *prog;

list_for_each_entry_rcu(prog, &head->plist, link) {

qdisc_skb_cb(skb)->tc_classid = prog->res.classid;

if (tc_skip_sw(prog->gen_flags)) {

filter_res = prog->exts_integrated ? TC_ACT_UNSPEC : 0;

} else if (at_ingress) {

__skb_push(skb, skb->mac_len);

bpf_compute_data_pointers(skb);

filter_res = BPF_PROG_RUN(prog->filter, skb);

__skb_pull(skb, skb->mac_len);

} else {

bpf_compute_data_pointers(skb);

filter_res = BPF_PROG_RUN(prog->filter, skb);

}

if (prog->exts_integrated) {

res->class = 0;

res->classid = TC_H_MAJ(prog->res.classid) | qdisc_skb_cb(skb)->tc_classid;

ret = cls_bpf_exec_opcode(filter_res);

if (ret == TC_ACT_UNSPEC)

continue;

break;

}

if (filter_res == 0)

continue;

if (filter_res != -1) {

res->class = 0;

res->classid = filter_res;

} else {

*res = prog->res;

}

ret = tcf_exts_exec(skb, &prog->exts, res);

if (ret < 0)

continue;

break;

}

return ret;

}

where the method calls BPF_PROG_RUN() to execute our BPF code.

So finally, this ends our journey!

4.1 Intro

XDP happens before BPF hooking points, so it’s more efficient - even the skb

hasn’t benn allocated when XDP programs are triggered.

Borrow a picture from [4,5]:

XDP needs hardware (NIC) support.

4.2 Code (TODO)

TODO: more elaborations on this section.

5.1 tcpdump hooking point

tcpdump happens before tc-bpf hooking point, but after XDP hooking point. That’s why we could capture the traffic in section 2, but would not if we’re running XDP ones.

5.2 Netfilter framework

Netfilter is another hooking and filtering framework inside Linux kernel, and is widely used (e.g. with iptables frontend).

BPF hooking happens before netfilter, and is more efficient than the later. For example, it is possible now to entirely bypass the netfilter framework in Cilium.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh