2022-6-13 23:11:50 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:47 收藏

Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference for 2022 has just closed out and with it we have had our first look at macOS 13, aka macOS Ventura, slated for public release in the last quarter of 2022. As usual, Apple has added some headline-grabbing new features such as the Stage Manager viewing mode and the ability to use Quick Look in Spotlight search results, but there are more interesting – and potentially disruptive – changes with macOS Ventura that have received less attention. In this post, we highlight seven major changes that will be of interest to enterprise security teams and Mac administrators.

1. Ventura Hardware Limitations | Can Your Enterprise Macs Run macOS 13?

A new OS can sometimes mean new hardware for those that want to adopt it and any security improvements it may promise, and Ventura drops support for more Mac hardware than any other recent version of macOS.

You’ll need a machine that’s no older than 2017, and in the case of the MacBook Air and the Mac Mini models, advance that one more year to 2018. For Mac Pro owners, you’ll need something newer than the iconic “trash can” version – only Mac Pro’s from 2019 onwards support macOS 13 Ventura.

Here’s the full list of Macs that support macOS 13 Ventura:

- MacBook 2017 and later

- MacBook Pro 2017 and later

- iMac 2017 and later

- iMac Pro 2017

- MacBook Air 2018 and later

- Mac Mini 2018 and later

- Mac Pro 2019 and later

2. Gatekeeper in Ventura – Fortified, But Still Flawed

Gatekeeper is Apple’s first line of defence in its model of check, block and remove. Whereas MRT.app has traditionally dealt with removal and XProtect with blocking certain kinds of common malware, Gatekeeper’s role is to ensure that when users execute some code, that code meets the local system policy. The policy includes checks such as whether the code is validly signed and whether it has been tampered with in certain ways.

Prior to Ventura, these checks are only performed the first time the code is run. That means a malicious actor or malicious process could still alter the code of apps and executables after they have passed their first Gatekeeper check.

Now in Ventura, Gatekeeper’s responsibilites have been extended to include checking that notarized apps have also not been modified subsequently to that first launch by unauthorized processes. Apple says that Gatekeeper will allow apps to be modified by some processes – a vital function for things such as updates – but those processes need to be explicitly allowed by the developer.

This is welcome news, and it should help fight malicious hijacking of legitimate apps already on the user’s system. However, the Gakeeper check here is overridable by users. When an unauthorized modification is attempted, Gatekeeper throws a warning and asks the user if they want to allow it in System Settings.

Expect to see some creative social engineering attempts around this weak spot, as well as some intensive scrutiny by security researchers. Based on previous macOS architecture, we would anticipate that this “user consent” will be under the control of the notoriously buggy TCC framework.

3. Paths to Persistence – Warnings for Login Items, LaunchAgents and LaunchDaemons

Perhaps one of the biggest – or at least most noticeable – changes to both security and the user experience is the change to the venerable old System Preferences application. Renamed and redesigned, System Preferences app is now ‘System Settings.app’.

The iOS-style makeover will be controversial among long-time Mac users. Some will say a redesign was well overdue and that the iOS styling adds consistency to the ‘Apple experience’, while others will argue that a UI designed for touch doesn’t transition well to a keyboard-based form factor. However you feel about it, what is certain is that you’ll need to use the search field to find your way around in the list-based interface.

From a security angle, one new feature is that users can now manage Login Items, LaunchAgents and LaunchDaemons all from a single place. Previously, the only visibility into items that execute when the device starts up or the user logs in required finding hidden directories in the Finder, using the Terminal, or relying on 3rd party software. This has always been problematic, particularly with LaunchAgents, since any process can add a persistence item without authorization from or notification to the user.

Now in macOS Ventura, not only can users see which items are set up for persistence, they can also control them from a single place in System Settings. Importantly, when apps add a LaunchAgent, LaunchDaemon or Login Item, the system now generates a notification alert (or two…).

As LaunchAgents are the single most widely used means of persistence by macOS malware, this can only be a good thing. The extra visibility and control over this process is certainly a good thing from a security perspective, and this is a long overdue and important improvement to macOS security that we welcome.

Inevitably, however, there are caveats that enterprise teams need to be aware of. This extra security to protect against malware and misuse will also impact the vast majority of software that uses these items legitimately. First, there are the extra alerts to work through and dismiss. In some cases, as in our example above, one installation may produce more than one alert. Secondly, and perhaps more worryingly, users may not understand the impact of disabling such items in System Settings.

If your organization uses essential software with such persistence mechanisms, you will want to figure out what kind of support calls you might receive if a user disables these. At present, it is not clear whether the final release of Ventura will include the ability to lock down these items via MDM or some other mechanism to prevent users disabling critical software.

4. Passkeys – Is It the Beginning of the End for Phishing Attacks on macOS?

In collaboration with Google, Microsoft and other industry players, Apple has been working on a new logon technology for web and other remote services called ‘passkeys’. Passkeys are meant to replace passwords and to overcome the multiple security problems that passwords present. Passwords are easily phished from users or stolen from servers and provide the gateway to account takeover and enterprise compromise.

Passkeys aima to solve the problems with passwords. They are essentially a form of public-private key encryption, with a private key generated and held securely on the user’s device and a public key on the server. Each passkey is generated by the device and guaranteed to be strong and only ever used for a single account. Users don’t need to remember them as the device will allow the user to choose available passkeys automatically when they try to log onto a service. Touch or FaceID is used to verify that the person accessing the passkey is the owner of the account.

To make passkeys as portable as passwords, however, they need to be synced across a user’s devices, and that means – at least in Apple’s case – via iCloud Keychain. So long as a user has one device with them that has passkeys stored, they can use that device to log in to shared or public computers by means of authentication via QR codes. Interestingly, the devices presenting and scanning the QR codes need to be in close physical proximity – in fact, within Bluetooth range of each other – making email and other common phishing techniques “impossible”.

Apple says that “entire categories of security problems, like weak and reused credentials, credential leaks, and phishing, are just not possible anymore” with passkeys. We hope that’s true, but of course we will have to see how attackers adapt to – or bypass – this security innovation.

5. Wave Goodbye to Captchas (And Thanks for All The Bridges)

Aside from Passkeys, macOS Ventura aims to improve the logon experience of users accessing remote servers by bringing an end to the need for the dreaded “Captchas”.

Seriously, Google? pic.twitter.com/j0PArdxuZw

— Justin Searls (@searls) July 5, 2018

Captchas are meant to prevent robots and automated scripts from attempting to access services that should only be accessed by actual human beings, and they are in widespread use as part of the fight against fraud. As almost anyone who has ever used one will attest, however, they can be frustratingly difficult at times. They also present issues for Accessibility and can negatively impact certain kinds of users. On top of that, Apple says, CAPTCHAs tend to be used with tracking or device fingerprinting technologies such as IP capture, posing a risk to privacy.

With macOS 13 Ventura, Apple has introduced Private Access Tokens in the hope that these will eventually make Captchas a thing of the past. While the technical details of how PATs work is one we’ll leave for the developer documentation, the takeaway for users is that as developers begin to adopt PATs in their apps and on their servers, the prevalence of CAPTCHAs on macOS should begin to dwindle.

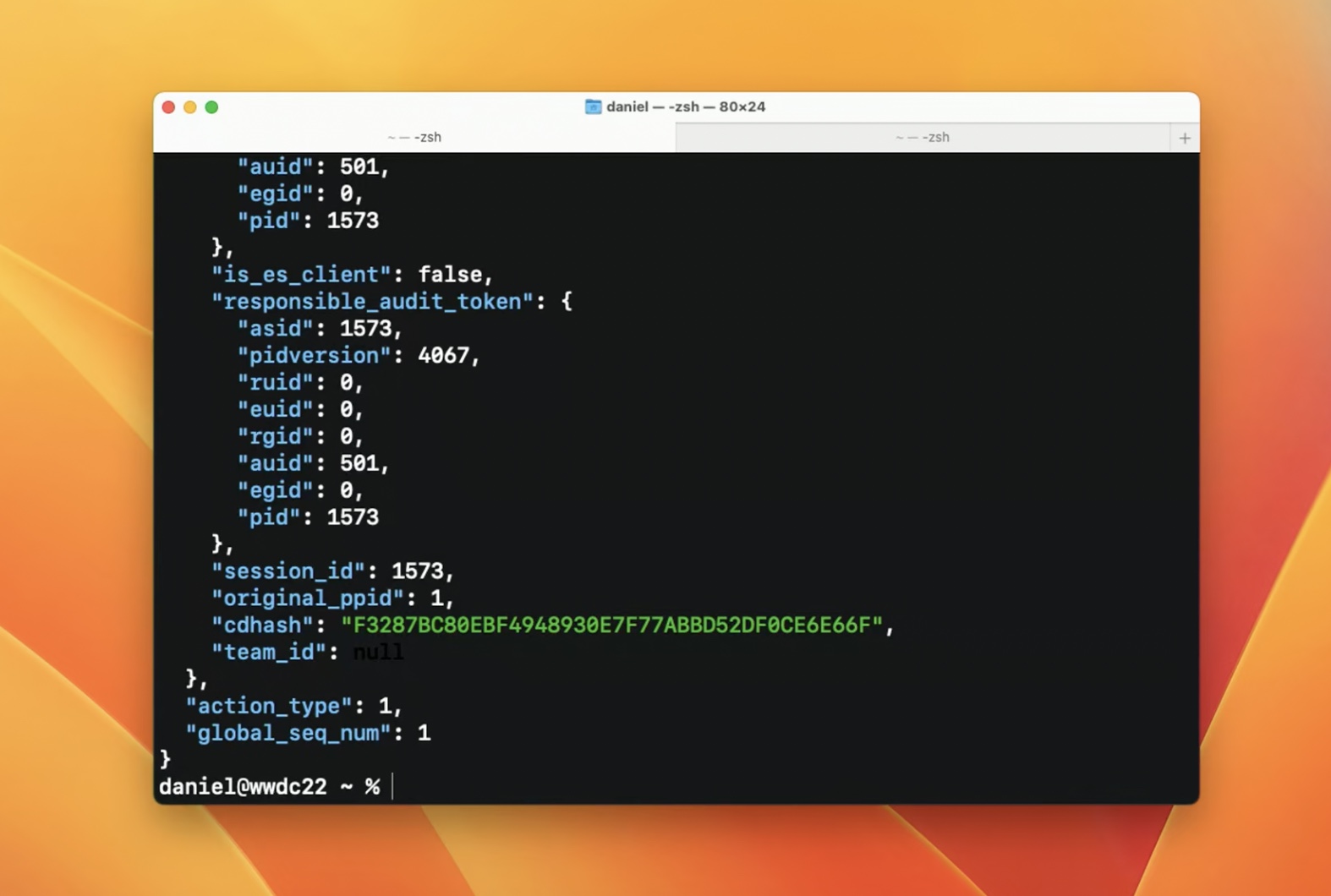

6. ESLogger | Visibility for Security Researchers

One of the things we, and we suspect many security-focused IT teams, are excited about in macOS Ventura is the potential of the new ESLogger command line tool. It’s not often that Apple gives us new tools to play with that are specifically targeted at security, but ESLogger looks like it may be extremely useful for security practitioners, malware analysts and threat detection engineers.

As per the tools man page, ESLogger interfaces with the Endpoint Security framework to log ES events, which can be output to file, stdout or the unified logging system.

Apple has also renewed its commitment to 3rd party security products by adding further NOTIFY events to the ES framework, and ESLogger supports all 80 NOTIFY events that are now available in macOS Ventura. ESLogger offers much needed and convenient visibility into security-relevant events for researchers without needing to deploy a full ES client.

7. Improved DNS Security With DNSSEC

With macOS 13, Apple has brought in support for developers wishing to use DNSSEC and DNS with DDR in their applications. As most security teams know, DNS is fraught with problems due to the fact that it can be easily snooped and spoofed. That’s because DNS neither supports encryption nor authorization, making it possible for attackers to conduct attacks like DNS Cache poisoning, in which an attacker switches the genuine DNS data for a particular website and redirects requests from a client app to a site controlled by the attacker.

With DNNSSEC (Domain Name Security), developers can now ensure that their apps are only talking to who they are meant to be talking to and that data they receive has not been intercepted and changed along the way.

According to Apple, “DNSSEC protects data integrity by attaching signatures in responses. If a response is altered by an attacker, the signature of the altered data will not match the original one. In that case, the client can detect the altered response and discard it.”

DNSSEC is a specification created by the IETF. Apple says that while a number of DNS service providers already support it, client support is not widespread. With DNSSEC now being supported in both macOS Ventura and iOS 16, it’s hoped that this will accelerate adoption and decrease the number of attacks through this vector.

Conclusion

With this latest iteration of macOS, Apple has made some bold – and, in general, largely welcome – security improvements. Of these, the two most important being that Gatekeeper now checks that previously approved code hasn’t been subsequently modified and that users receive UI notifications when Login Items, LaunchAgents or LaunchDaemons are added. There are, of course, other ways for malware to persist in macOS, and we are sure it won’t be long before creative malware authors start utilizing them.

In that regard, it is also important to see that Apple has renewed its commitment to 3rd party security tools with further events added to the ES framework, and we look forward to seeing how ESLogger will help our researchers in their investigations and malware analysis going forward.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh