文章探讨了生成式AI和智能体AI的快速发展及其带来的安全治理挑战。强调非人类身份(NHI)的安全管理至关重要,包括API密钥、服务账户等。作者指出,尽管AI工具提升了效率,但缺乏严格的治理措施可能导致严重漏洞。建议采用零信任架构、短期凭证和权限细分来降低风险,并通过跨团队协作和标准化方法加强治理能力。 2026-1-9 16:39:47 Author: securityboulevard.com(查看原文) 阅读量:4 收藏

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a broad field with many practical applications. Over the past few years, we have seen explosive growth in generative AI, driven by systems like ChatGPT, Copilot, and other interactive tools that help developers write code and users create content. More recently, we have also seen the rise of "Agentic AI," in which orchestrators coordinate actions across one or more AI agents to perform tasks on behalf of a user.

While that can sound futuristic, even here in 2026, the reality is a little simpler.

AI systems, no matter how they are deployed, are just processes running on machines. They may live on a laptop, in a container, inside a virtual machine, or deep in a cloud environment. Fundamentally, they are software executing instructions, albeit probabilistic ones rather than hard-coded deterministic programs. And like every other subsystem we have ever built, they need a way to communicate safely.

This is where our real problem begins.

As we rush to adopt agentic AI, we are repeating a familiar mistake. We are focusing on capability and speed while leaving non-human identity (NHI) security and governance as an afterthought, by connecting AI tools to sensitive systems (repos, cloud, ticketing, secrets) without consistently applying least privilege. That gap has existed for years with CI systems, background jobs, service accounts, and automation.

Agentic AI is not inventing the gap, but it is quickly widening it.

Trust Decides Everything

Security in any system, whether it is a chatbot, a CI worker, or a long-running daemon, eventually boils down to trust.

Who is making the request? What are they allowed to do? And under what specific conditions?

Modern architectures focus on "zero trust," but many of these systems still rely on a single fragile factor for access: long-lived secrets, often taking the form of API keys or never-expiring certificates. The risk really comes from keeping static tokens in environment variables, dotfiles, build logs, or shared vault paths accessible to many processes, including AI tools. When those access keys leak, anyone who finds or steals them can grab everything the secret allows access to, until someone notices.

What zero trust actually requires is separation of concerns.

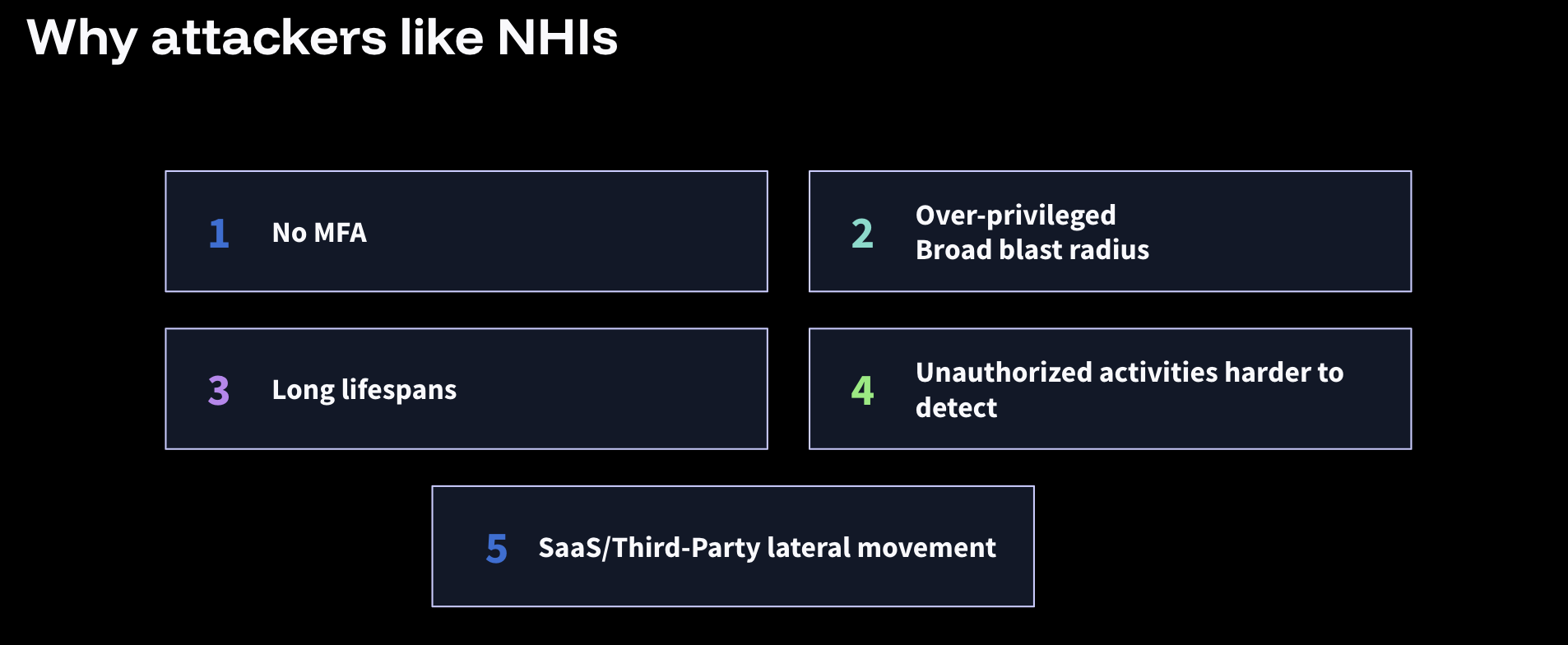

Authentication should prove that an entity is who or what it claims to be. Authorization should define exactly what that entity is allowed to do. Without that separation, we end up granting broad, standing permissions that are difficult to track, difficult to revoke, and extremely attractive to attackers.

This is the heart of non-human identity (NHI) governance. NHIs are broadly defined as anything that is not a human but still authenticates and connects to other running systems. This includes bots, scripts, workloads, service accounts, and CI jobs. And now, that list includes agents and agentic systems.

The control plane is the same. Identity, ownership, lifecycle, and permissions. Agentic AI, fundamentally, does not alter this reality. Under the hood, these systems are all advanced math, running on a chip somewhere.

What feels different is how we interact with them. We give them names like Claude and Cursor. We assign them personalities. We treat them like coworkers rather than workloads.

That anthropomorphization subtly shifts how we, as humans, think about trust and responsibility.

Ironically, that shift can be helpful.

Agents: NHIs in CI Pipelines, Terminals, and Browsers

Once you start treating an agent like an actor, not too dissimilar from a human, it becomes easier to apply time-tested identity patterns. OAuth, a delegated authorization standard, and OpenID Connect, the identity layer on top of OAuth, exist because we learned, over decades, that standing privilege does not securely scale. Short-lived, verifiable credentials usually beat permanent keys. Scoped permissions beat “just give it access” every time, from a safety perspective.

This "agents as if they were human actors" analogy does break down in some key places, though. For example, since agents have no fingerprints or ability to stop and pull out their phone, traditional multi-factor authentication cannot be bolted onto a background process. But the core idea holds: every entity accessing a system should be provable, attributable, and constrained.

That becomes obvious when you follow agents into the environments where they actually operate.

Where CI Meets The Robot

Continuous integration pipelines are no longer just build scripts. It is the complex dance where code becomes reality, pulling in dependencies, relying on task runners, and hopefully passing thorough testing and review processes.

If an agent can read a failing build, modify code, open a pull request, and iterate until green, that is a productivity win. It also means the agent needs access to repositories, build logs, artifacts, and sometimes deployment pathways. CI already has a history of being over-permissioned because teams value uptime and speed over locked-down security postures.

Agents tend to inherit that bias. “Give it what it needs” becomes “give it everything so it does not block the sprint.”

Agents In The Command Line

In terminals, the risk is less glamorous and more common. Terminals are full of implicit trust, which looks like environment variables, config files, copied tokens, and debugging output. These habits all made sense when only a human was driving or could access the guarded developer's machine.

Agents in a terminal context can act quickly, which is the point. They can also surface secrets quickly, copy them into logs, paste them into tickets, or echo them into places you did not intend, as we saw in repeated attacks across 2025, such as Nx's S1ngularity and Shai Hulud. It’s enough to have secrets stored in places that are routinely copied, logged, or shared during debugging. Agentic tools can increase the volume and speed of this copying, which raises the likelihood of accidental exposure unless guardrails, including redaction, scanning, and review, are in place.

You do not need sci-fi for things to go wrong. You just need carelessness with credentials and a system that rewards moving fast.

On Your Behalf Across The Internet

In browsers, the stakes are higher because browser agents often operate within authenticated sessions. This is the sharp edge of “acting on your behalf.” If an agent can click around internal tools, approve actions, download data, or change configuration through an admin console, the question is which identity is it using? What permissions does it have? Can you reconstruct what happened later and tune for those edge cases?

This is why framing agents as NHIs is so useful. It avoids the fantasy. It forces the boring questions:

- Who owns the agent, and who gave it those permissions?

- What is its lifecycle?

- What is it allowed to do, precisely?

- How do we observe and audit its actions?

If you cannot answer those, your organization is not “doing agentic AI.” It is running ungoverned automation at scale. And that is dangerous.

Governance that scales starts with inventory and alignment

Treating NHIs, including AI agents, with rigor sounds obvious until you try to do it. The hard part is not the principle. It is the grind.

The work starts with understanding what you already have. Inventory is unavoidable.

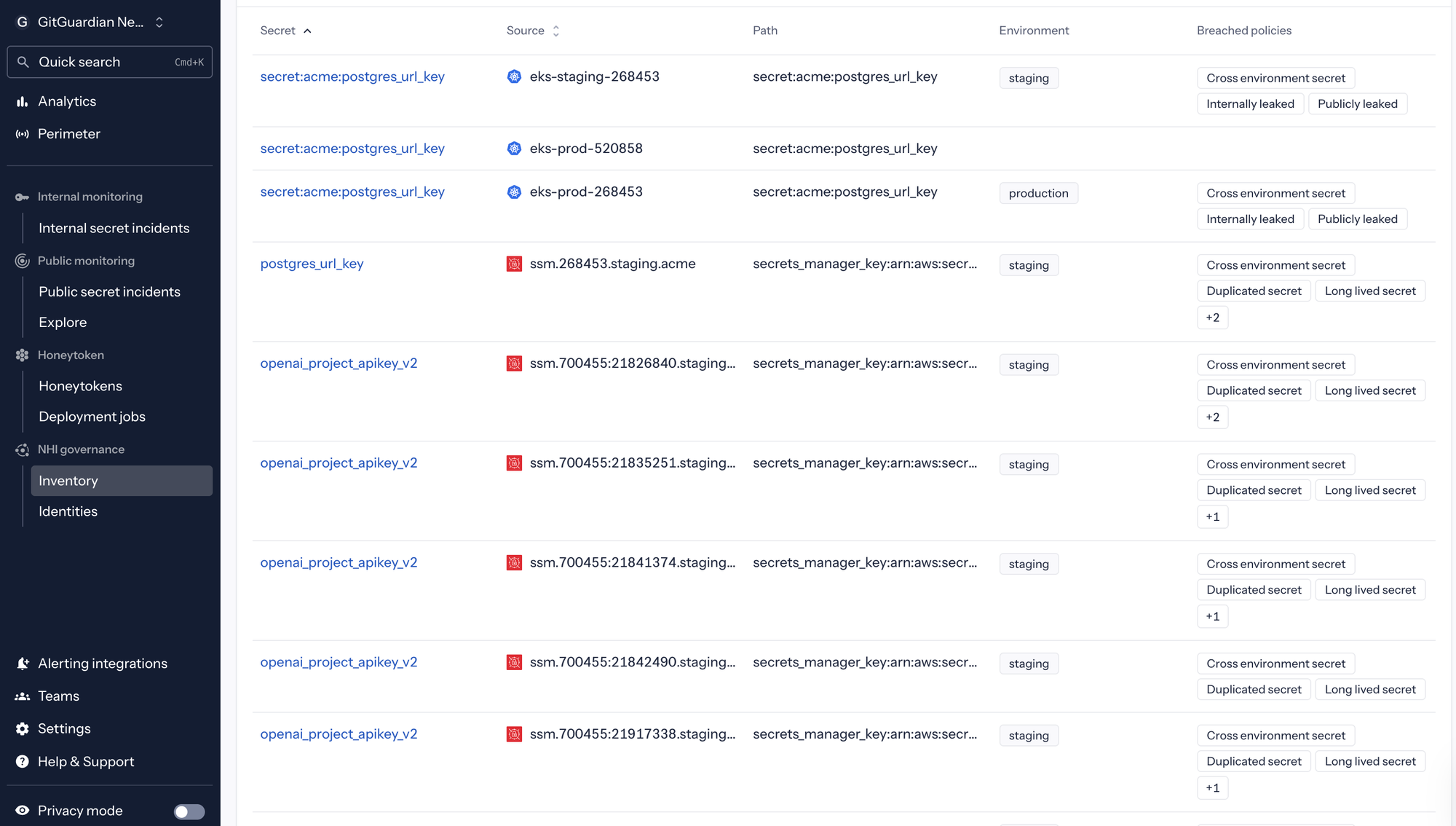

There is no shortcut around accounting for existing credentials, services, agents, and automations. This traditionally has been slow, difficult, and often uncomfortable work, especially in legacy environments. But it is also where progress begins, because you cannot reduce risk you cannot see.

Inventory also forces a second reality into the open: accountability for permissions.

Who Owns That Agent?

If an agent can access a system, that access was provisioned by someone: either explicitly, via tokens, OAuth grants, service accounts, or implicitly, by running inside an already-authenticated session. The governance challenge is ensuring every access path has a named owner, least-privilege scope, auditability, and a rotation/revocation process

While it would be convenient to have a person to blame, like the developer who set everything up and then left, the reality of ownership and accountability is more nuanced and requires a shift in how we think about responsibility models.

Every team needs to be accountable for rotation, revocation, and incident response. This is the difference between governance and hope. When ownership is unclear, offboarding fails, cleanup stalls, and leaks become prolonged incidents.

There is also the organizational challenge and reality that, to get NHI governance under control, it will require creative collaboration across traditionally siloed parts of the business. No single team can own identity and access management at scale across all humans, workloads, agents, and whatever evolves next.

Who Accounts For That Agent's Access?

IAM, DevSecOps, security, platform, and development teams all touch this problem from different angles. Success depends on alignment around shared north stars, not isolated tooling decisions made under delivery pressure.

For years, non-human identity evolved bottom-up. Developers solved immediate problems with whatever mechanism worked. That flexibility helped systems scale, but it also created fragmentation, duplication, and governance gaps. As agentic AI becomes operationally significant and strategically imperative, the pendulum is swinging back.

Compliance, auditability, and cost control are pushing organizations toward more standardized approaches.

The good news is that the ecosystem is catching up. Workload identity, short-lived credentials, and policy-driven access are no longer niche ideas. They are becoming default building blocks.

Tools that help organizations discover and govern secrets and NHIs, including GitGuardian’s NHI Security and Governance platform, are moving from “nice-to-have” to foundational. Not because they are trendy, but because you cannot govern what you cannot find, and you cannot respond to leaks without context.

What We Should Learn From Agentic AI About NHIs

Agentic AI is a forcing function. It is showing us, in bright light, the identity failures we have tolerated for years. What’s new is how quickly a mis-scoped token, inherited session, or leaky log can be exercised.

Any entity that can act on your behalf must be treated with the same seriousness as human access, regardless of whether it runs for a millisecond or maintains a long-lived connection.

Transformation will not happen overnight. Inventory, cleanup, and migration take time. They have to scale across teams and technologies. That is normal. Plan for it.

Alignment matters more than tools. Without shared strategy and governance, agentic AI will simply accelerate the same failures we have been living with, including long-lived keys, unclear ownership, broad standing permissions, and poor offboarding. Those, in turn, lead to more breaches and incidents.

All non-human identities face the same fundamental problems. They all need verifiable identity, least-privilege access, and continuous oversight. Agentic AI is not a special case. It is a stress test.

The teams that succeed will be the ones that treat it that way, early, and build the governance that makes speed survivable.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from GitGuardian Blog - Take Control of Your Secrets Security authored by Dwayne McDaniel. Read the original post at: https://blog.gitguardian.com/what-ai-agents-can-teach-us-about-nhi-governance/

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh