嗯,用户让我总结一下这篇文章的内容,控制在一百个字以内,而且不需要用“文章内容总结”之类的开头。直接写描述就行。 首先,我得通读一下这篇文章。看起来是关于一个Linux后门的分析,叫做TinySHell。文章里提到这个后门是一个轻量级的ELF二进制文件,用来隐藏元数据,连接到C2服务器,并执行命令或者启动远程shell。它的设计很隐蔽,适合长期间谍活动。 接下来,文章详细介绍了如何提取这个后门的配置信息。他们用到了capa、Capstone和LIEF这几个工具。capa用来检测能力,识别二进制的功能;Capstone用于反编译和分析指令;LIEF则用来提取加密字符串。 具体步骤是这样的:首先用capa找到RC4加密函数的位置,然后用Capstone分析指令,找到RC4密钥和加密数据的位置。接着用LIEF提取.rdata节中的加密数据,并解密得到配置信息,比如C2地址和端口。 总结一下,这篇文章展示了如何结合静态分析工具和行为规则匹配来提取恶意软件的配置信息。这对于安全分析来说非常重要,因为配置信息通常包含攻击者的指令和目标服务器的信息。 现在要把这些内容浓缩到100字以内。要抓住关键点:TinySHell后门、轻量级设计、隐藏机制、配置提取方法、使用的工具(capa、Capstone、LIEF)、以及提取过程中的步骤(定位RC4函数、获取密钥、解密数据)。 可能的结构是:介绍后门及其特性,然后说明如何通过工具提取配置信息,并强调这种方法的有效性。 最后检查一下字数是否符合要求。 </think> 文章介绍了一种基于开源后门TinySHell的轻量级Linux后门,其设计隐蔽且持久,通过RC4加密隐藏配置数据。文章详细描述了利用capa、Capstone和LIEF等工具提取后门配置的过程,包括定位RC4解密函数、获取密钥及解密C2服务器信息的方法。 2025-12-22 09:32:13 Author: blog.sekoia.io(查看原文) 阅读量:5 收藏

In the third part of our series ‘Advent of Configuration Extraction’, we dissect a lightweight Linux backdoor, that is derived from an open-source backdoor called TinySHell. It is designed to provide silent, persistent remote access to compromised servers. The malware consists of a stripped ELF binary that hides most identifying metadata, a networking component that connects to its command-and-control server using a custom authentication protocol, and a backdoor module capable of executing commands or spawning a remote shell. Its simplicity, minimal footprint, and removal of recognizable strings make it highly stealthy and effective for long-term espionage activities.

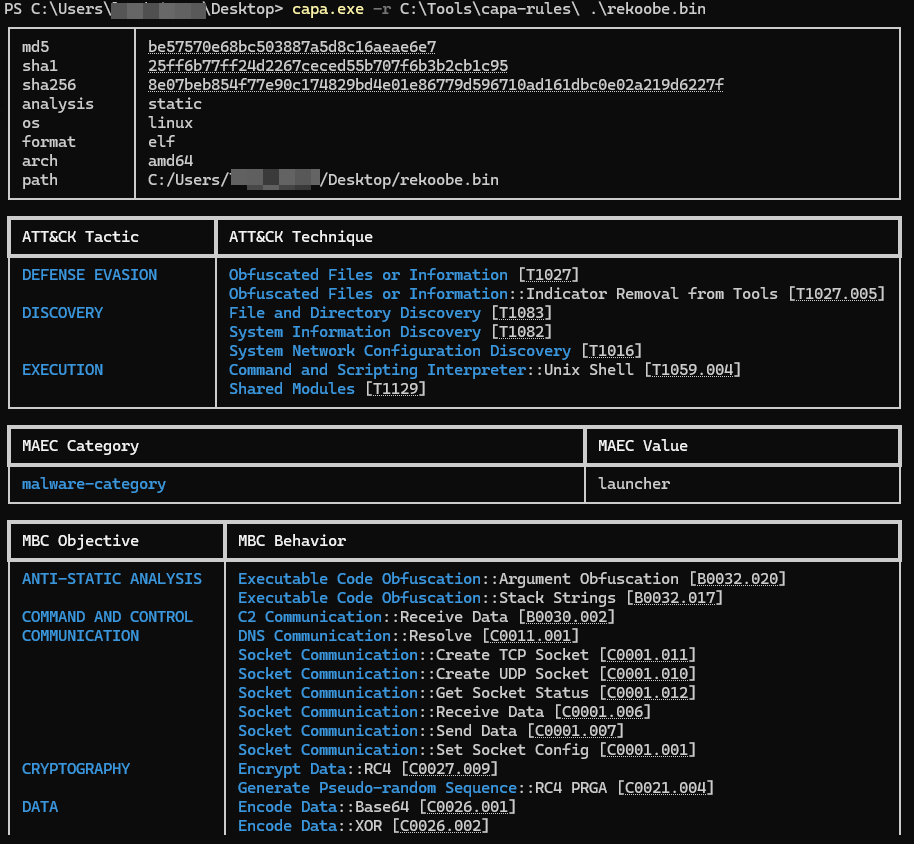

The sample 8e07beb854f77e90c174829bd4e01e86779d596710ad161dbc0e02a219d6227f available on Malware Bazaar is used to highlight the configuration extraction development process.

Before digging into the main topic of this report, this section makes a rapid tour of capa, in order to understand the central piece of the configuration extractor.

FLARE capa is an open-source capability detection tool for malware analysis that identifies what a binary does rather than how it is implemented. It can work standalone or integrate with disassembly frameworks like IDA or Ghidra. capa statically analyzes executables (PE, ELF, Mach-O, shellcode), extracts features such as API calls, strings, instructions, control flow patterns, and embedded data, and matches them against human-readable YAML rules describing high-level behaviors (e.g., process injection, keylogging, persistence). Rules are evaluated hierarchically across multiple scopes (instruction, basic block, function, file), producing a concise list of detected capabilities.

Each rule explicitly defines the scope at which it applies, meaning all required features must be present within the same instruction, basic block, function, or the entire file. This scoping model prevents unrelated features from being incorrectly combined across different parts of the binary and enables precise behavioral attribution (e.g., identifying a specific function responsible for injection). Rules express feature requirements using declarative logic constructs (AND, OR, NOT), quantifiers (e.g., “N or more occurrences”), and optional conditions. capa also supports rule dependencies, allowing complex capabilities to be composed from simpler ones by referencing other rules. During analysis, capa extracts features once, then evaluates rules bottom-up from lower to higher scopes, caching matches and resolving dependencies to produce explainable results with clear evidence linking each detected capability to the underlying code locations.

The backdoor obfuscates its string using RC4 encryption. This routine is invoked multiple times throughout the binary to retrieve various pieces of information, such as Linux file path, Command-and-Control (C2) configuration data and feature activation flags. As mentioned earlier, the malware binary is stripped, meaning that no symbols are available to help identify functions of interest during the configuration extraction process.

The extractor approach differs from those presented in the previous articles [Part-1, Part 2]. Since the string containing the C2 is obfuscated using RC4, the primary strategy consists of locating the corresponding decryption function within the binary. To achieve this, the extractor relies on capa. Then, the extractor leverages Capstone to manipulate the instructions to retrieve the decryption key and finally it uses LIEF to extract the encrypted strings.

Locate RC4 function

As a first step, the standalone capa tool can be used, or alternatively its plugin version in a decompiler, to understand what to look for and in which context the targeted function operated. By inspecting the FLARE-capa view in IDA, the tool matches one of its rules named “encrypted data using RC4 PRGA” and returns the address of the corresponding function (in this sample, 0x402c81).

Based on the plugin results, it is possible to clearly determine where and how the RC4 function is used. This is achieved by identifying cross-references to the function and analyzing its callers to determine the arguments, how they are supplied, and where the corresponding data are stored within the binary.

CAPA Instrumentation

To locate the RC4 function, the extractor relies on the Python package flare-capa. In order to keep the pipeline lightweight and maintainable, not all default capa rules are loaded. However, to obtain a functional flare-capa setup in Python, the extractor requires a minimal subset of rules, specifically:

- “encrypt data using RC4 PRGA”

- “calculate modulo 256 via x86 assembly”

- “contain loop”

The “contain loop” and “calculate modulo 256 via x86 assembly” rules are mandatory, as the RC4 rule depends on them for correct matching. These rules can be imported as shown below:

import textwrap

from pathlib import Path

import capa.main

import capa.rules

import capa.loader

import capa.engine

import capa.features.common

import capa.features.address

rc4_capa_rules = [

capa.rules.Rule.from_yaml(

textwrap.dedent(

""" <edited encrypt data using RC4 PRGA>

""")

),

capa.rules.Rule.from_yaml(

textwrap.dedent(

""" <edited contain loop>

""")

),

capa.rules.Rule.from_yaml(

textwrap.dedent(

""" <edited calculate modulo 256 via x86 assembly>

""")

),

]

rules = capa.rules.RuleSet(rc4_capa_rules)

extractor = capa.loader.get_extractor(

Path(ELF_PATH),

"auto",

"auto",

capa.main.BACKEND_VIV,

[],

should_save_workspace=False,

disable_progress=True,

)

capabilities = capa.capabilities.common.find_capabilities(

rules, extractor, disable_progress=True

)

meta = capa.loader.collect_metadata(

[], Path(ELF_PATH), "auto", "auto", [], extractor, capabilities

)

meta.analysis.layout = capa.loader.compute_layout(

rules, extractor, capabilities.matches

)

for name, value in capabilities.matches.items():

if name == "encrypt data using RC4 PRGA":

for match in value:

print(f"address of the RC4 function is 0x{match[0]:x}")Code 1. Code to use capa rule within Python script

In this context, only the RC4 capa rule is relevant. This is why the extractor embeds only a limited subset of capa rules. In a more global use case—such as a generic file classification or signature-based analysis—the full default set of capa rules should be imported and leveraged to provide an initial overview of a new sample.

Play around with RC4

The RC4 identification represents an important initial milestone. However, the extractor still requires an understanding of how the RC4 key and the encrypted data are passed to this function. Figure 2 illustrates the instructions that precede the call to the RC4 decryption routine. Basically, by looking at one of the cross-references to the RC4 function in a disassembler (e.g.: 0x402c81).

The function takes three arguments:

- The address of the data to be decrypted.

- The length of the encrypted data.

- The RC4 key.

As shown by Figure 3, the key is constructed as a stack-string and its address is supplied to the function via a (LEA) instruction. Consequently, the extractor targets a sequence of instructions that move immediate values—interpreted as string fragments—onto the stack.

For this, the extractor uses Capstone to disassemble the binary and provides Python objects to play with. Firstly, it lists the cross-references to the RC4 function by enumerating each instruction until a call instruction is found whose target is the RC4 function identified previously. Then it reads the instructions which precedes the call to find the stack-string containing the RC4 key. Since the key is represented as a string, it can be reconstructed by identifying mov instructions that write immediate values to stack offsets, for example:

potential_rc4_keys = defaultdict(bytes)

for offset, insn in enumerate(self.instructions):

if insn.id == X86_INS_CALL:

if (insn.operands[0].type == X86_OP_IMM

and insn.operands[0].imm == self.rc4_function_address):

# this is the equivalent of searching for x-refs to the RC4 function

for index, prev in enumerate(self.instructions[offset::-1]):

if prev.id == X86_INS_MOV:

if len(prev.operands) != 2:

continue

op1, op2 = prev.operands

if op1.type == X86_OP_MEM and op2.type == X86_OP_IMM:

if op2.imm >= 0 and op2.imm <= 255:

# ensure its is a valide key

potential_rc4_keys[

op1.mem.base

] += op2.imm.to_bytes()

if index > 50:

break

if any(

map(lambda x: x.startswith(b"\x00"), potential_rc4_keys.values())):

break

Code 2. Python snippet to list x-ref to the RC4 function and search for stack string instructions

Note that, the identified key are stored backwards as the instructions that build the key are read this way, the extractor adds a short intermediate hack to put them in the correct order.

Where is Blob?

At this step of the process, the extractor is able to identify the RC4 function and retrieve the key that is shared for all encrypted strings. Then, it requires enumerating the encrypted blobs, in particular the one containing the C2 address.

To achieve this, the extractor can adopt one of two strategies:

- Apply the same backward-analysis approach used for the RC4 key, extracting the encrypted data address from the instructions preceding each RC4 function call.

- Identify the memory region where the encrypted data are stored.

In the analyzed samples, the encrypted data are conveniently stored contiguously in the .rdata (read-only data) section. For this reason, the extractor follows the second approach which is the simplest one.

To do so, it uses Lief to retrieve the data of the specific .rdata section, then the extractor splits them on null bytes. Each string is decrypted using the decryption routine provided by malduck. Malduck is a Python package that compiles various implementations used for malware analysis such as cryptography, compression, hashing algorithms, etc…

The configuration is stored in a string that has the following format:

<C2 address>:<C2 port>;<flag 1>;<flag 2>;<flag 3>;

Once the extractor finds a decrypted string that matches this format, a straightforward function parses the string to retrieve only the indicator of compromise.

In this report, we presented a complete configuration extraction pipeline for the backdoor, highlighting how capa can be effectively embedded into a Python-based extractor to identify cryptographic routines in stripped binaries. By leveraging a minimal subset of capa rules, the approach remains lightweight while still providing precise detection of the RC4 decryption function used to protect configuration data.

The extractor combines Capstone for disassembly and cross-reference analysis, and targeted backward instruction tracing to reconstruct stack-based RC4 keys and locate encrypted data.

Finally, by identifying and decrypting the obfuscated configuration blobs—stored contiguously in the .rdata section in the analyzed samples—the extractor successfully recovers elements such as the C2 server configuration.

The complete code of this extractor is available on our github repository.

This fourth article concludes the Sekoia.io TDR Advent of Config Extractor series and illustrates how combining focused static analysis techniques with behavioral rule matching can significantly streamline malware configuration extraction workflows.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh