An important concept in Usable Security is whether a given UI represents a “security surface.” Formally, a security surface is a User Interface component in which the user is presented with information they rely upon to make a security decision. For example, in the browser, the URL in the address bar is a security surface. Importantly, a spoofing issue in a security surface usually represents a security vulnerability.

Just as importantly, not all UI surfaces are security surfaces. There are always many other UI surfaces in which similar information may be presented that are not (and cannot be) security surfaces.

Unfortunately, knowing which surfaces are security surfaces and which are not is simultaneously

- Critically important – If you think an untrustworthy surface is trustworthy, you might get burned.

- Unintuitive – There’s usually no indication that a surface is untrustworthy.

Eight years ago, Chromium wrote a document listing the Chrome browser’s security surfaces. Approximately no one has ever seen it.

Non-Security Surfaces

Perhaps the most famous non-security surface is the “status bubble” shown at the bottom left of the browser window that’s designed to show the user where a given link will go:

There are many reasons why this UI cannot be a security surface.

The primary issue is that it’s below the line-of-death, in a visual area of the page that an attacker can control to paint anything they like. The line-of-death is a major reason why many UIs cannot be considered security surfaces — if an attacker has control over what the user sees, a UI cannot be “secure.”

But even without that line-of-death problem, there are other vulnerabilities: most obviously, JavaScript can cancel a navigation when it begins, or it can rewrite the target of a link as the user clicks on it. Or the link could point to a redirector site (e.g. bit.ly) rather than the ultimate destination. etc.

Challenging Security Surfaces: The “URL Bar”

Perhaps the most complicated security surface in existence is the browser’s address bar, known in Chromium-based browsers as the “Omnibox”.

That omnibox naming reflects why this is such a tricky security surface: Because it tries to do multiple things: It tries to be a security surface which shows the current security context of the currently-loaded page (e.g. https://example.com), but it also tries to be a information surface which shows the full URL of the page (e.g. https://example.com/folder/page.html?query=a#fragment), and it tries to be an input surface that allows the user to input a new URL or search query. Only certain portions of the URL information are security-relevant, and the remainder of the URL could be used to confuse the user about the security-relevant parts.

Making matters even more complicated, the omnibox also has to deal with asynchronicity — what should be shown in the box when the user is in the middle of a navigation, where the user’s entered URL isn’t yet loaded and the current URL isn’t yet unloaded?

Windows LNK Inspection

Earlier this year, a security vulnerability report was filed complaining that Windows File Explorer would not show the full target of a .lnk file if the target was longer than 260 characters.

The reporter complained that without accurate information in the UI, a user couldn’t know whether a LNK file was safe.

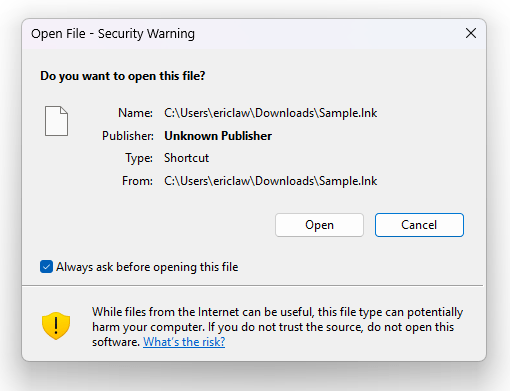

This is true, but it’s also the case that the user isn’t being asked to make a security decision in this dialog; the UI where the user is asked to make a security decision doesn’t even show the target at all:

Even in the exceptionally unlikely event that a user uses Explorer’s LNK inspection UI, very few users could actually make a safe determination based on the information within. Ultimately the guidance in the Security Warning prompt is the right advice: “If you do not trust the source, do not open.”

The Windows team ended up fixing the display truncation earlier this year, but not as a security fix, just a general quality bug fix.

Impatient optimist. Dad. Author/speaker. Created Fiddler & SlickRun. PM @ Microsoft 2001-2012, and 2018-, working on Office, IE, and Edge. Now working on Microsoft Defender. My words are my own, I do not speak for any other entity. View more posts