Webshells are malicious scripts/programs that are uploaded to compromised web servers. Most webs 2025-11-26 00:46:25 Author: www.hexacorn.com(查看原文) 阅读量:14 收藏

Webshells are malicious scripts/programs that are uploaded to compromised web servers. Most webshells are written in JSP, ASP, PHP and they are interpreted by a dedicated script processor/interpreter executed by the web server (f.ex. Apache, IIS, Tomcat). The results of that processing are rendered into a content that is sent back to the client – typically a web browser, but more advanced offensive tools may choose a different communication protocol.

Once a webshell is installed, it allows the attacker to use the compromised web server for various purposes. The attacker can use it to steal web server data and code, attack other systems, act as a proxy, host phishing content/landing zones, give hacktivists an ability to deface a web site, impersonate web server owner, and do many other things…

The reason I talk about them in this series is because sandboxes don’t handle webshells well. And yes, analysing webshells is actually not an easy task, in general…

First the good news. There are still many cases today where very well-known webshells are being used by attackers, attackers who are not making any effort to change the code of these classic web shells.

Then the worse news: it is becoming more and more common nowadays that many of the web shells are obfuscated, code-protected (various wrappers and extensions), password-protected, many rely on POST instead of GET requests (which means that the parameters included in POST requests are usually not logged by the web server), and some more advanced webshell payloads can be very well hidden inside the legitimate server-side code (making them harder to spot). As you can imagine, manual webshell analysis of these more complicated cases is very time-consuming and non-trivial. This is because in most these cases there it now the authentication bit that we need to take care of… In other words, when you access a more modern webshell today, you often need to provide a password, token, secret to access that particular webshell’s GUI. So, if it is not included in an outer code layer of a webshell, we need to either find it via opportunistic hash cracking, leak, or, if lucky, borrow it from other researchers who were luckier and somehow got a hold of it… Anyone having an experience manually analysing webshells like this knows that it is a very time consuming game, and one that doesn’t necessary guarantee the positive outcome…

Luckily, not all cases are like this.

Many of the old-school webshells will still load and execute their code with no problem, they don’t include any guardrails, and are often instantly rendering a user-friendly interface, presenting its features to a curious analyst in their full glory.

Additionally, a lot of webshell functionality existing today is often… accidental. Many web developers don’t have any cybersecurity experience, they don’t validate the input, they don’t sanitize the output and happily include code in their creations that takes whatever the input user-controlled parameters provide, and push it directly to some very dangerous shell functions that can be easily fooled into running some unexpected code…

And this is why sandboxes should be used to analyse web-server code; same as they analyze traditional executables.

We can argue that at the very basic level, sandbox webshell (or, more precisely: web server code) analysis should:

- provide at least a screenshot of how the suspicious script is being rendered by a browser,

- allow the analyst to inspect the code, ideally, unwrapped,

- highlight references to GET and POST variables, and

- perhaps support interactive analysis by letting the analyst play around with the sample during the session, and allow them to send hand-crafted GET or POST requests (if lucky, manual code analysis can help to discover required credentials that will grant access to the web shell’s GUI).

So, with that… let’s look at some very practical aspects of web server code analysis from a sandbox designer’s perspective. Depending on the file type, we need to create an environment within the test system that is able to execute/interpret scripts on a server-side (web server running locally), and then present the results of script execution on a client side (browser), and then combine them to present the final results to the sandbox user.

Analysis of JSP scripts

- Download and install the latest Java Development Kit.

- Download and install the latest Apache Tomcat installer.

- Now you can access Tomcat Web Server on http://localhost:8080/.

- You can drop a JSP sample in c:\Program Files\Apache Software Foundation\Tomcat <version>\webapps\test\<file>.jsp, and access it via http://localhost:8080/test/<file>.jsp.

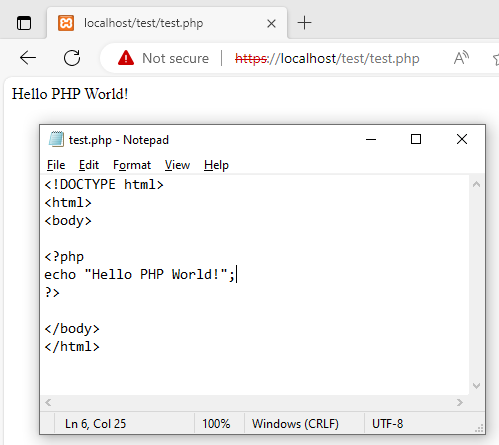

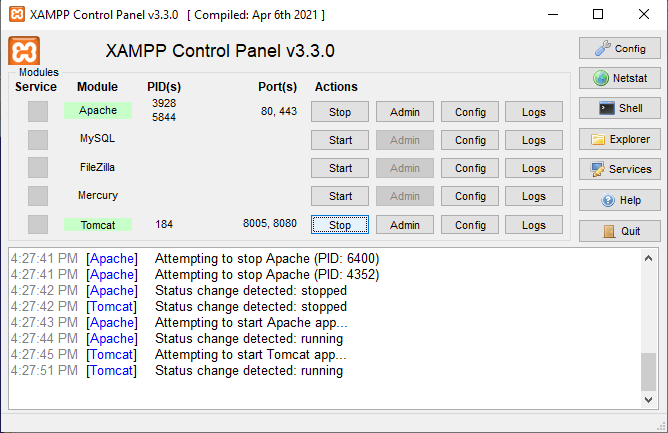

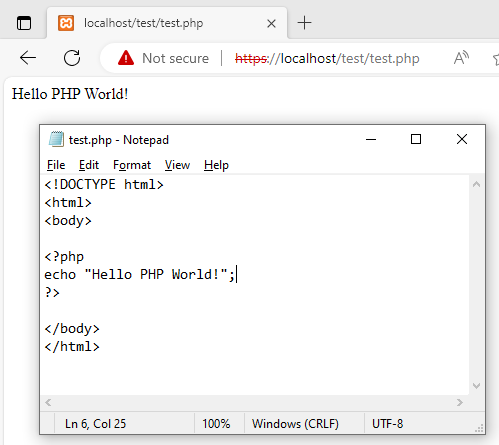

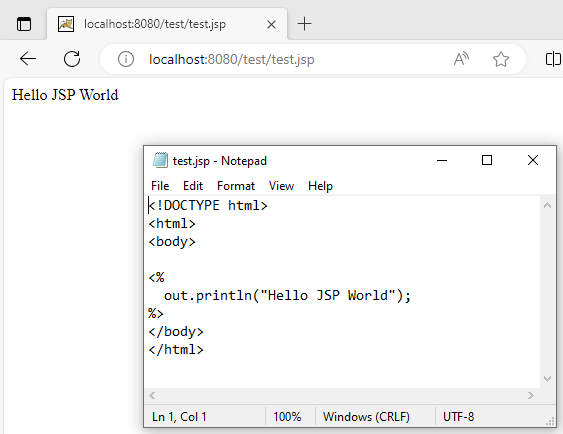

Analysis of JSP and PHP scripts

- Download and install the latest Java Development Kit.

- Download and install the latest XAMPP.

- Now you can access Apache Server on http://localhost/ and https://localhost/, and then Tomcat Web Server on http://localhost:8080/.

- You can drop PHP sample into c:\xampp\htdocs\test\<file>.php and access it via http://localhost/test/<file>.php and https://localhost/test/<file>.php.

- You can drop JSP sample into c:\xampp\tomcat\webapps\test\<file>.jsp and access it via http://localhost:8080/test/<file>.jsp.

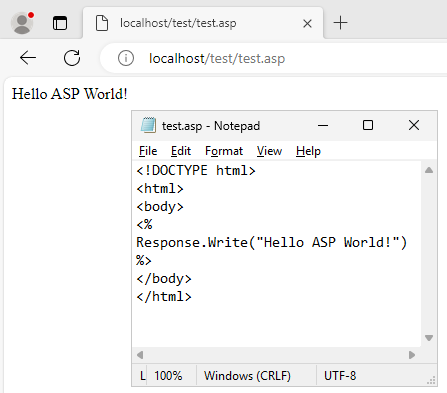

Analysis of ASP scripts

- Install Windows Server of your choice, f.ex. Windows Server 2025.

- Install IIS and ASP support following this guide or others.

- Now you can access IIS Web Server on http://localhost/.

- You can drop ASP sample into c:\inetpub\wwwroot\test\<file>.asp and access it via http://localhost/test/<file>.asp.

Running possible web server scripts under Apache, Tomcat, IIS servers in an automatic fashion is cool, but we know it is just the first piece of puzzle.

If we are lucky, and the web server script code is not obfuscated, we can make an attempt to analyze its code, even if in a rudimentary way. The goal is to discover the following:

- is the code recognized by any yara rule?

- does the script expect GET, POST, or both requests ?

- how are these retrieved? (there are multiple ways to do it f.ex. $_GET, $_SERVER[‘QUERY_STRING’] in PHP)

- what are the names of parameters passed to the script ?

- is the code obfuscated/wrapped/hidden/protected?

- can we analyze the script code to understand if there are any:

- hardcoded values in it, possibly usernames/passwords

- hashes of hardcoded values in it, possibly of usernames/passwords

- URLs/IPs it is connecting to

- files it writes to

- references to known webshell functions that help to compress/decompress, code/decode data&code, execute/interpret code f.ex. base64_decode/base64_encode, gzdeflate/gzinflate, str_rot13, eval, system, etc.,

- references to string/character/hexadecimal/decimal/octal manipulation functions that are often used by webshells to construct dynamic code,

- references to functions that may shed light on the code functionality f.ex. file operations, directory operations, file downloading/uploading, program execution, privilege escalation, etc.,

- references to known webshell authors, ASCII ART of hacking groups, etc.

As you can see, there are many ways to improve our webshell sandbox analysis experience…

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh