文章描述了通过 Azure Active Directory 中的 Global Administrator 角色滥用权限的风险。攻击者可通过密码喷射获取 Office 365 全局管理员账户,并利用该账户在 Azure 中获得管理权限。这可能导致攻击者控制 Azure 虚拟机和 Active Directory 域控制器,进而引发全面的安全威胁。 2020-5-27 19:17:0 Author: adsecurity.org(查看原文) 阅读量:3 收藏

While Azure leverages Azure Active Directory for some things, Azure AD roles don’t directly affect Azure (or Azure RBAC) typically. This article details a known configuration (at least to those who have dug into Azure AD configuration options) where it’s possible for a Global Administrator (aka Company Administrator) in Azure Active Directory to gain control of Azure through a tenant option. This is “by design” as a “break-glass” (emergency) option that can be used to (re)gain Azure admin rights if such access is lost. In this post I explore the danger associated with this option how it is currently configured (as of May 2020). The key takeaway here is that if you don’t carefully protect and control Global Administrator role membership and associated accounts, you could lose positive control of systems hosted in all Azure subscriptions as well as Office 365 service data. Note: Most of the research around this issue was performed during August 2019 through December 2019 and Microsoft may have incorporated changes since then in functionality and/or capability.

Attack Scenario: In this scenario, Acme has an on-premises Active Directory environment. Acme embraced Azure Infrastructure as a Service (IAAS) as an additional datacenter and deployed Domain Controllers to Azure for their on-prem AD (as their “cloud datacenter”). Acme IT locked down the DCs following hardening advice and limited Azure administration to the VMs hosting the DCs. Acme has other sensitive applications hosted on servers in Azure. Acme signed up for Office 365 and started a pilot. All of the Active Directory and Exchange admins (and many other IT admins) are granted temporary Global Administrator (aka Global Admin or GA) rights to facilitate the pilot.

Screenshot captured September 2019

The Attack: The attacker password sprays the Acme Office 365 environment and identifies a Global Admin account that doesn’t have MFA (multi-factor authentication). Since less than 10% of Global Admins have MFA configured, this is a real threat.

The attacker creates a new Global Admin account (or leverages an existing account). In this example, the Office 365 Global Admin account “AzureAdmin” is compromised.

Attacker Moves from Office 365 Global Admin to Shadow Azure Subscription Admin

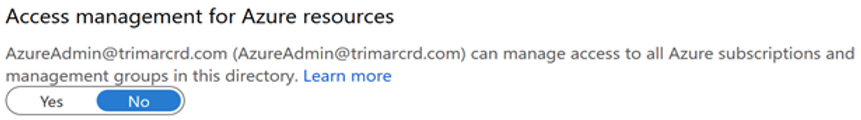

The attacker sets this account to be able to “Access management for Azure resources” by toggling the “No” to “Yes”. While this option is configured in the Directory Properties section, this is actually a per account configuration option. This “magic button” provides the ability to manage Azure roles, but no direct Azure rights (to VMs).

According to Microsoft documentation, toggling this option from No to Yes, adds the account to the User Access Administrator role in Azure RBAC at the root scope (which has control over all subscriptions in the tenant). This option is only available to accounts that are members of the Global Administrator role.

What’s interesting is that if this option is toggled to “Yes” that the account is removed from the Global Administrator role, the Azure RBAC role remains and is not removed. In fact, the account can’t toggle this option back to “No” until it has Global Admin rights again.

The attacker determines that Acme has a few on-prem AD Domain Controllers in Azure. In order to exploit this configuration the attacker decides to create a new account and use that one to access Azure. With Azure access management enabled for the attacker-controlled account (called “hacker” so I wouldn’t forget which account I was using), this account can logon to the Azure subscription management and modify roles.

Monitoring for changes to the root Azure RBAC group “User Access Administrator” is a bit complicated since there doesn’t seem to be any way to view this in the Azure portal. The primary method to review is through Azure CLI.

Once there is an account identified that needs to be removed, it must be removed using the Azure CLI (since this is a root level role).

If one attempts to remove an account from the subscription role, the following message appears since it must be removed at the root level.

Let’s pause here for a moment and recap the configuration so far.

- The attacker compromises a Global Admin account by password spraying Acme’s Office 365 tenant and finds one with a bad password (& no MFA).

- The attacker authenticates with this account and leverages the account rights to either create another account used for the attack or use the compromised account.

- The attacker toggles the “Access management for Azure resources” option to “yes” which adds the Azure AD account to the Azure RBAC role “User Access Administrator” at the root level which applies to all subscriptions.

- User Access Administrator provides the ability to modify any group membership in Azure.

- The attacker can now set any Azure AD account to have privileged rights to Azure subscriptions and/or Azure VMs.

Attacker updates Azure role membership to run commands on Azure VM(s): Setting “Owner” rights to this account is obvious (and is possible as is adding an account to Virtual Machine Administrator). This would result in an attacker controlled account having full access to Azure VMs.

While exploring the various Azure RBAC roles, I realized a more stealthy method is “Virtual Machine Contributor” which sounds pretty innocuous.

Virtual Machine Contributor, according to the Azure roles description: (https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/role-based-access-control/built-in-roles#virtual-machine-contributor) “lets you manage virtual machines, but not access to them, and not the virtual network or storage account they’re connected to.” [quote excerpted in September 2019]

This sounds like very limited access to the Azure VM until you consider the ability to run PowerShell (as System) on the VM. This right is Microsoft.Compute/virtualMachines/runCommand/action which is included in Virtual Machine Contributor.

This includes the ability to re-enable the Administrator account. Which on a Domain Controller in Azure, this would be the RID 500 account for the domain.

Once the attacker can run PowerShell on the Azure VM, they can execute commands as System. I added the obvious “hacker” account and a secondary one that looks “normal” (maybe?) called “Azure AD Service Account. Both of these can run PowerShell commands.

In this example, I run a PowerShell command to run “net localgroup” which updates the local Administrators group. When this is executed on a Domain Controller, this applies to the domain Administrators group. This will happen on the Azure based DC, then replicate to the DCs on-prem.

I then run the Active Directory module PowerShell command to get the membership of the domain Administrators group and we can see that the account was added.

Assuming PowerShell logging is enabled (and sent to the SIEM), it’s possible to see this command execution. Based on my experience, this isn’t common.

Once the attacker can run PowerShell as System on the Azure VM, they can extract anything from the cloud hosted Domain Controller, including the krbtgt password hash which means total compromise of the on-premises Active Directory environment. In this example, the attacker runs a one-liner Invoke-Mimikatz PowerShell command that dumps the password hash of the AD krbtgt password hash. Note that the way I run it here, this would require internet access. However, it would be possible to obfuscate and host Invoke-Mimikatz on a compromised system on the corporate network and leverage that instead.

Conclusion: The customer is hosting on-premises Active Directory Domain Controllers in the Azure cloud.The customer also has Office 365 with admin accounts that are not appropriately protected. The attacker password sprays the company’s accounts and identifies the password for an Office 365 Global Administrator. With this account, the attacker pivots to Azure and runs PowerShell on the Azure VM which hosts the company’s on-prem Active Directory Domain Controllers. The PowerShell command can update the domain Administrators group in Active Directory or event dump the krbtgt password hash which enables the attacker to create Kerberos Golden Tickets offline and then use forged Kerberos TGT authentication tickets against the on-prem AD environment to access any resource.

Why is this issue important?

- Customers usually have no expectation that an Office 365 Global Administrator has the ability to control Azure role membership by flipping an option on the account (under Directory Properties of all places).

- Microsoft documented Global Administrator as an “Office 365 Admin”, not as an Office 365 and Azure administrator (or at least having that capability.

- Office 365 (Azure AD) Global Administrators can gain Azure subscription role administration access by toggling a single switch.

- This issue involves Azure AD since that component provides the Global Admin the ability to gain Azure role administrator rights as well as Azure since there is no additional step or notification that an Office 365 Global Administrator has selected this option.

- Azure doesn’t have great granular control over who can run commands on Azure VMs that are sensitive like Azure hosted Domain Controllers (or other applications hosted on customer Azure VMs).

- An attacker can compromise an Office 365 Global Administrator, toggle this option to become the Azure IAM “User Access Administrator”, then add any account to another Azure IAM role in a subscription, and then toggle the option back to “No” and the attacker account from the User Access Administrator IAM role with minimal logging and nothing clearly identifying in Azure AD that “Access management for Azure resources” was modified for an account and no default Azure logging alerts to this.

- Once the “Access management for Azure resources” bit is set, it stays set until the account that toggled the setting to “Yes” later changes it to “No”.

- Removing the account from Global Administrators does not remove this access either.

Logging & Detection As of early 2020, it’s not possible to check for Azure AD accounts with this “Access management for Azure resources” bit set (either via the Azure AD portal or programmatically). Furthermore, it’s not possible to remove this setting as an Azure AD Global Administrator even if it could be detected on another account. Only the account that sets it can remove it. There appears to be no clear logging of any of this activity (in Office 365, Azure AD, or Azure logs) as I walked through my attack chain on this. The only clear detection I could identify is by monitoring the Azure RBAC group “User Access Administrator” membership for unexpected accounts.

Detection Key Points:

- Can’t detect this setting on Azure AD user accounts using PowerShell, portal, or other method.

- No Office 365/Azure AD logging I can find that states that an Azure AD account has set this bit (“Access management for Azure resources”).

- No Audit Logs logging that clearly identifies this change.

- Core Directory, DirectoryManagement “Set Company Information” Log shows success for the tenant name and the account that performed it. However, this only identifies that something changed relating to “Company Information” – no detail logged other than “Set Company Information” and in the event the Modified Properties section is empty stating “No modified properties”.

- No default Azure logging after adding this account to the VM Contributor role in Azure.

Azure AD to Azure Mitigation:

- Monitor the Azure AD role “Global Administrator” for membership changes.

- Enforce MFA on all accounts in the Global Administrator role.

- Control the Global Administrator role with Azure AD Privileged Identity Manager (PIM).

- Monitor the Azure RBAC role “User Access Administrator” for membership changes.

- Ensure sensitive systems like Domain Controllers in Azure are isolated and protected as much as possible. Ideally, use a separate tenant for sensitive systems.

MSRC Reporting Timeline:

- Reported to Microsoft in September 2019.

- MSRC responds in early October 2019: “Based on [internal] conversations this appears to be By Design and the documentation is being updated. “

- Sent MSRC additional information in mid October 2019 after a day of testing detection and potential logging.

- MSRC responds that “most of what you have is accurate”

- Sent MSRC update in late January 2020 letting them know that I would be submitting this as part of a larger presentation to Black Hat USA & DEF CON.(2020).

- MSRC acknowledges.

- Sent MSRC notification that I would be sharing this information in this blog.

- MSRC Security incident still open as of May 2020.

I was informed by Microsoft during my interactions with MSRC that they are looking into re-working this functionality to resolve some of the shortcomings I identified.

(Visited 1 times, 1 visits today)

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh