文章描述了一次成功的跨站脚本(XSS)攻击测试过程。作者通过修改POST请求中的用户输入字段,在目标应用中注入恶意代码,并成功触发alert弹窗显示document.domain。过程中克服了输入过滤机制的限制,展示了多种绕过方法的有效性。 2025-8-14 13:29:48 Author: redsiege.com(查看原文) 阅读量:8 收藏

by Larry Ellis

Background

Coming off my time in the defensive world in the military, I’ve always had an interest in web application testing. Flipping the script from out-thinking an attacker to out-thinking a developer was always an enticing concept to me. I’ve tried the Hack the Box, TryHackMe, and “juice shop” types of exercises in a training environment. However, in the real world, finding the same vulnerabilities was a struggle.

My curse has always been all of my user input injection attempts were properly sanitized and/or validated by the in-scope web applications. Also, I lacked knowledge of advanced user input filtering bypass concepts commonly used to evade most web frameworks. Finally, my time spent on research, and hands-on training, paid off during a recent engagement. In this blog post, I’m going to go through the steps I used to eventually conquer the site and alert document.domain.

Setting The Stage

The target was an application used to display images and items in a matrix. The user could pull, for example, an image of an abdomen with some sort of genetic deficiency.

When the matrix is generated by clicking the “generate matrix” button, the request was sent via a POST request with the checkbox information in the payload of the POST. The checkbox information was also visible in the inspect-element pane of the web browser.

There are different methods to inject XSS, including POST and GET. Here, we have an editable field that’s processed via a POST request. This sounds like a promising candidate for a cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability.

The Exploit

First, let’s try to get it to alert something to the browser window. Keep in mind, we don’t have to rely on only alert() for this to work. Console.log() can also be used in the same way and is more likely to be allowed due to developers needing a way to debug their code.

![]()

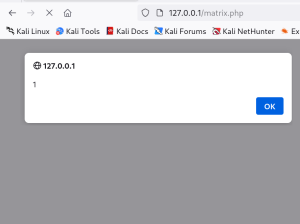

Modified Attribute

Success!

Great! After generating the matrix with our edited input, we were able to coerce the application into alerting to our screen the number 1. In this specific case, no part of the input was changed inside of the quotes and was interpreted literally behind the scenes. But what does that really do for us? We need to attempt to alert something like document.domain to demonstrate code execution actually ran on the affected application.

But here lies the issue!

When switching from a simple alert like “1” to alerting document.domain, nothing alerts to the screen.

![]()

Document.Domain

It appears the application is checking for document.domain, either because we’re still inside the quotes of the name attribute, or because of the “onload” event handler we’re using.

In the past, I would have chalked this up to input being caught or not being able properly escape HTML tagging and just been happy with the fact that an alert was generated at all. However, it dawned on me that if we could escape the quotes and change our event handler type, that could be enough to fool whatever was in place to catch me and alert document.domain.

![]()

New Event Handler

When crafting this new payload, the first step was to close out the current quote and tag using a quote. Then, we create our own brand-new HTML image tag with a bad source. When the application attempts to render our image, it will error due to a bad source, causing the on-error event handler to trigger; in our case, alerting document.domain.

document.domain

Success! Using a different event handler and escaping the quotes, we were able to dodge whatever mechanism was stopping document.domain from being revealed!

Wrapping Up

When hunting for user input vulnerabilities like cross-site scripting, it’s important to remember there’s more than one way we can get events to trigger, and different methods of dodging input sanitization to demonstrate the vulnerability does exist and its associated impact. A great free tool can be found here, to help you discover different ways of testing user input vulnerabilities.

Remember on your next engagement to try several different methods of escaping HTML entities before throwing in the towel.

About Larry Ellis, Security Consultant

Larry Ellis has worked in IT and Security for 10 years in rolls such as Help Desk, Incident Response and Security Operations. He built the mission qualification training used by Air Force Incident Responders to prepare them to detect and respond to Nation State Threats. He also won the Air Force’s “Outstanding Cyber Warfare Airman” award for his contributions in defending the Korean Peninsula. Larry enjoys translating his defensive knowledge base to offensive security – bridging the gap in tactics, techniques and procedures between the two worlds.

Changing Directions: Attacking with Open Redirects

By Red Siege | August 7, 2025

by Stuart Rorer Open Redirection Whenever I think of open redirection, I think of Super Mario games and the green plumbing pipes. By hopping into one I can easily transport […]

Learn More

Eagle Eye: Efficient Directory and File Enumeration

By Red Siege | August 7, 2025

by Stuart Rorer Hide and Seek I always loved playing hide and seek as a kid, our house had a laundry chute in the upstairs bathroom which made it easy […]

Learn More

Penetration Testing in SDLC

By Red Siege | July 2, 2025

by Douglas Berdeaux Determining where in your software development lifecycle (SDLC) to have a penetration test carried out can be tricky. This article aims to guide new development shops at […]

Learn More

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh