What is Smishing?You will no doubt be familiar with phishing, which consists of sendin 2024-2-5 12:35:41 Author: www.vaadata.com(查看原文) 阅读量:3 收藏

What is Smishing?

You will no doubt be familiar with phishing, which consists of sending malicious emails to encourage people to perform sensitive actions, such as entering their credentials on a fake authentication page.

Smishing is very similar, except that the attacker does not send emails, but text messages, hence the name smishing. Essentially, smishing is nothing more and nothing less than SMS phishing.

Broadly speaking, smishing is a social engineering technique which uses a pretext to influence its victims and push them into action, via the SMS channel. In addition, phishing by SMS or email can be used for “mass” scams or more targeted attacks, as we will see later.

How to Identify a Smishing Attack?

Before going into detail about a concrete example of a grey box smishing campaign carried out as part of a social engineering penetration test, let’s take a look at some of the factors that need to be taken into account when identifying a malicious SMS.

The sender’s number

In the majority of Smishing attacks, the sender’s phone number is completely unknown to the recipient, which should be enough to set off alarm bells.

The telephone code – for example +33 for France, +1 for the United States and Canada, or +258 for Mozambique – may be more or less suspect.

To give text messages more weight, the attacker can try to spoof a number familiar to the victim. For example, there are platforms for sending SMS messages or even placing calls from a virtual number. The attacker can then choose the number before launching the attack.

It goes without saying that a text message is already more credible if it appears to come from a local number – i.e. one that is geographically close to us, in the same country or even the same town. With a bit of luck, the attacker can even spoof a number that is close to one known by his victim – with only a few digits difference.

Spoofing a familiar brand is another interesting alternative for attackers. It is common, for example, to receive a legitimate SMS from one’s own bank with the name of the organisation displayed instead of a phone number.

The attacker may also choose to send the SMS using a name rather than a traditional number. Depending on the nationality of the recipients, certain restrictions may apply, in particular certain names may be reserved in certain countries to prevent them from being spoofed. Spoiler alert: this is not the case everywhere!

Key points to remember:

- The sender’s number is not necessarily a foreign or inherently suspect number. Attackers can spoof a number familiar to their victims to lower their level of vigilance.

- In some cases, it is possible to spoof a well-known brand name and display an entity name in place of the phone number, making the attacks even more credible.

In short, the identity of the sender – be it a brand name or a phone number – should not be the sole criterion for determining whether an SMS is legitimate or not.

Content of the SMS

As well as the identity of the sender, which is naturally the first thing we look out for when we receive an SMS, there are certain clues in the body of the message itself that should warn us.

The pretext (Call-To-Sensible-Action)

The notion of pretext is not specific to smishing, but is a crucial element of any social engineering attempt, as it is what incites the victim to perform the sensitive action desired by the attacker.

For example, in a targeted attack aimed at a company’s employees, the attacker might use a VPN update as a pretext to get them to enter their credentials on a fake authentication page under his control.

To achieve its objective and spur users into action, the pretext must use various psychological levers to deceive their vigilance. It is often based on a sense of urgency (e.g. “please update within 48 hours or your account will be deactivated”), curiosity (“so-and-so has just shared the following folder with you”), familiarity (especially if the attacker impersonates a familiar sender), or even authority (if the presumed sender happens to be the company’s manager or IT department).

In the case of smishing, the attacker delivers his pretext by sending an SMS to his victims. The content of the message itself contains the request, which constitutes the essential part of the pretext, but other elements also play a part in the development of a good pretext (for example, the identity of the sender, the period during which the SMS is sent, etc.).

Links

Whether the attacker is distributing malware via an online platform or stealing login credentials, he will usually include at least one link to a domain under his control in the body of the SMS. However well-crafted the pretext, analysing this link properly – which takes a few minutes at most – can make all the difference.

To analyse a link, you first need to understand the concept of a domain name and the different levels that make it up.

Take, for example, the (legitimate) sub-domain login.microsoftonline.com. It breaks down as follows:

- The “.com” part corresponds to what is known as the Top-Level Domain (or TLD). Note that some TLDs are in two parts (such as “.co.uk”), but in the majority of cases the TLD is located after the last dot.

- Directly below the “microsoftonline” TLD is the Second-Level Domain (SLD). Together, the SLD and the TLD form what is commonly known as the domain name (here microsoftonline.com) – more precisely, it is the “TLD + 1”, since it includes the TLD plus the level immediately below it (i.e. the SLD)…

- Everything that follows (in this case “login“) identifies the sub-domain. There is no limit to the number of components (levels): auth.login.microsoftonline.com is an equally valid sub-domain.

As we have already said, a phishing link (most of the time) points to a malicious domain – i.e. a domain that is not the legitimate one (e.g. oultook.com instead of outlook.com).

As well as inverting, replacing or omitting characters in the legitimate domain name (a technique known as “typosquatting”), attackers use a number of other tricks to fly under the radar.

In the same spirit, “combosquatting” is the combination of a keyword and the legitimate domain (for example accounts–google.com instead of accounts.google.com). Changing the TLD is another possibility (e.g. gmail.co instead of gmail.com).

In all cases, you need to check whether the domain name (in the sense of “TLD + 1”) is legitimate or not. Here’s a quick test: what do you think of paypal.securelogin.com, for example?

Key points to remember:

- In most cases, the attacker’s aim will be to get you to perform a sensitive action (downloading a file or authenticating yourself on a more or less dubious website, for example). To do this, they will use certain psychological tricks to try to trick you into taking swift action.

- Systematically analyse the links received by SMS (by email or otherwise, incidentally), and in particular their domain name (“TLD + 1”).

Example of a Smishing Attack Carried Out During a Social Engineering Penetration Test

Now that we’ve looked at the clues you need to look out for to identify a smishing attempt, we’re going to put them into practice with an attack scenario, inspired by one of our audits.

Grey box Smishing campaign

In this example, we will be in a “grey box” condition, i.e. the business phone numbers of the employees to be targeted will have been provided to us by our customer, Koogivi.

It should be noted that in a “black box” condition – i.e. in the conditions of an external attacker with no information about the company – the search for the numbers to be targeted requires a more or less lengthy intermediate stage, as the numbers could potentially be divulged in several ways.

If an online platform is hacked, for example – which happens frequently – it is not uncommon to find contact information (including mobile numbers) in leaked data made public or sold on the dark web. More simply, LinkedIn profiles or email signatures can contain this type of information.

Reconnaissance

The reconnaissance phase is an important first step in our audits and, more generally, in any cyberattack, because it enables us to make an inventory of a company’s exposed assets and identify the most critical ones. It can also identify certain external services that are also potential entry points.

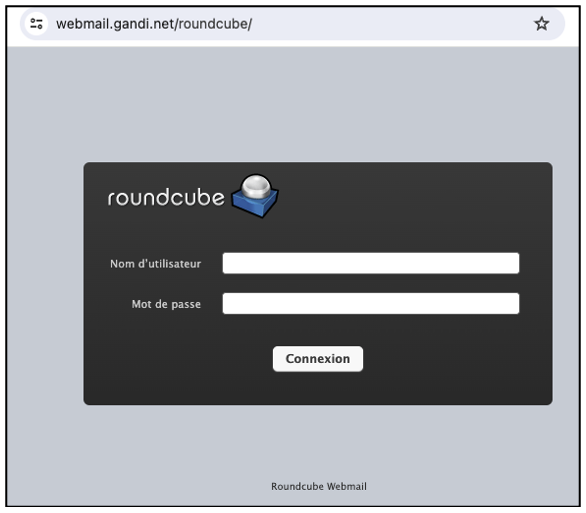

For example, let’s suppose that during our reconnaissance phase, we notice that Koogivi uses Gandi as its mail server (information revealed by MX records, for example). The webmail authentication page is as follows:

It goes without saying that webmail is an interesting point of entry for an attacker, as accessing it allows them to get their hands on potentially sensitive information – not to mention the fact that webmail passwords can give access to other internal (or external) platforms if they are re-used elsewhere.

Setting up the scenario

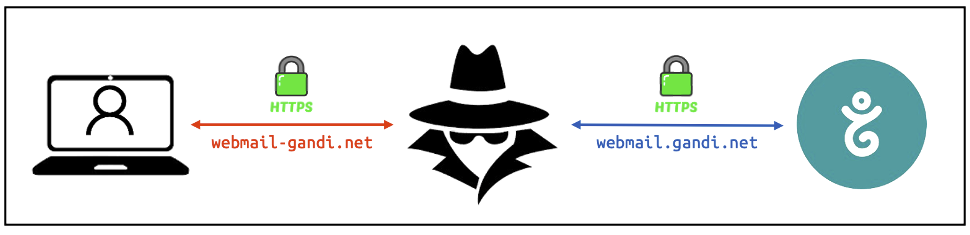

Once the target platform has been identified, the next step is to clone the authentication page. We won’t go into (too much) technical detail on this one, but you should be aware that certain techniques allow attackers to get their victims to interact not with a classic clone, but with the real application, thus bypassing most 2 factor authentication methods.

The idea is for the attacker to place himself in the middle of the interaction between his victim and the legitimate application (in short, in a man in the middle position), as shown in the diagram below:

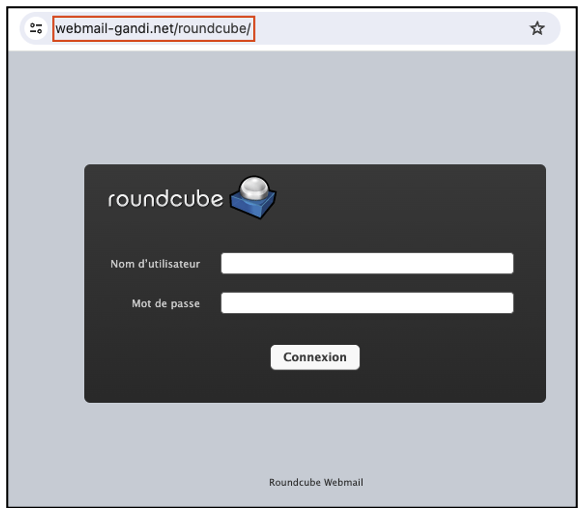

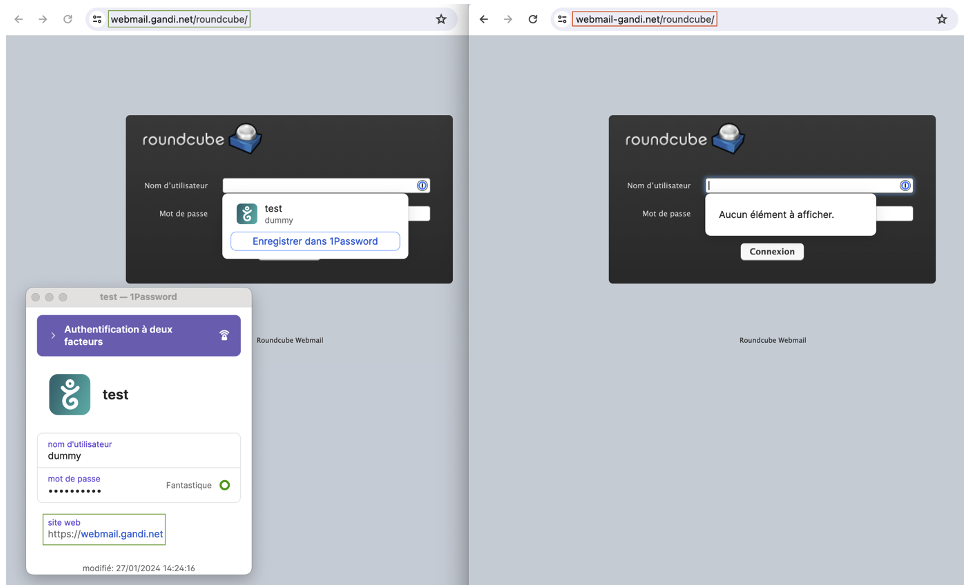

As you will have noticed, the malicious (“combosquatted”) domain we have chosen is webmail-gandi.net, which spoofs the legitimate webmail.gandi.net subdomain that hosts the legitimate authentication page. By proxying traffic between the victim and the legitimate application, the attacker can retrieve login credentials, including 2 factor authentication codes if any.

Once the malicious server has been configured, the fake login page looks like this:

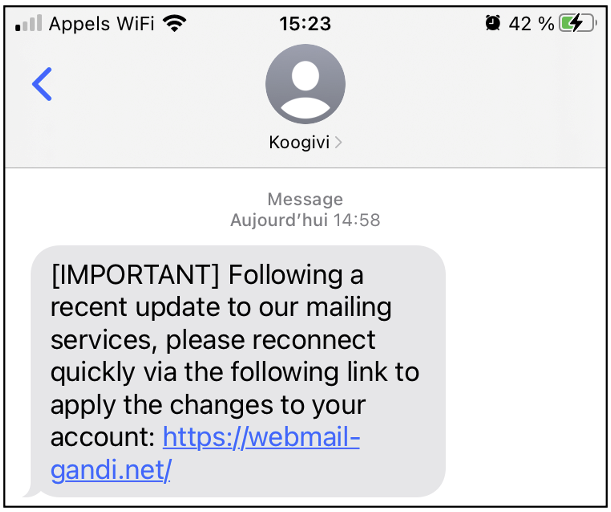

And that’s it! All that’s left is to send the SMS messages using a relevant and convincing pretext to encourage the recipients to connect to the fake webmail.

Execution and analysis

Combining everything we’ve just seen, here’s what the attack could look like:

The result is quite realistic, but let’s not be too quick to fall for it, and let’s take a look at the few clues we mentioned in this article:

- The sender ID is “Koogivi” and not a standard phone number. This is certainly the most convincing element of the pretext, but as we said above, the identity displayed to the recipient of the SMS is not infallible proof.

- The pretext plays on the notion of urgency in a fairly obvious way (with “[IMPORTANT]” and “quickly”) and will be all the more credible if Koogivi is used to communicating with its employees by SMS. If this isn’t the case, an email might be more effective than a text message (although not necessarily: if you change the message a little to say that the messaging service is unavailable, the choice of medium will make more sense). In any case, the right thing to do (easier said than done, I agree) would be to contact Koogivi’s IT department to make sure the request is legitimate, preferably using an alternative channel (in person or by email, for example).

- Finally, the link points to a domain combining combosquatting (a combination of “gandi.net”, which is the legitimate domain, and a keyword relevant to the pretext, in this case “webmail”) and typosquatting (the legitimate sub-domain is “webmail.gandi.net”, while the malicious domain is “webmail-gandi.net”). The right thing to do? Pay attention to the domain name (think “TLD + 1”), which in our case is “webmail-gandi.net” and not simply “gandi.net” (for the more adventurous, a quick WHOIS search on this domain name shows that webmail-gandi.net is not a domain registered by “Gandi SAS”).

How to Protect Yourself Against Smishing (and Phishing)?

Finally, let’s summarise the anti-*ishing hygiene rules we’ve just seen.

A quick aside: why “*-ishing”? Because the best practices that follow are applicable to all social engineering vectors – whether phishing by email, SMS (or more precisely smishing), Teams or post (and I could go on).

Generally speaking, our recommendations cover two main areas: awareness-raising and technical measures.

Raising risk awareness

Let’s start with the right reflexes that all employees should be aware of. First of all, to identify smishing attacks, you need to systematically take the time to analyse the key clues:

- The identity of the sender: who is sending me this message? As we have seen, it may be a telephone number (perhaps even a contact already registered) or a brand name (such as “LCL” or “Koogivi”). In any case, you shouldn’t rely on it blindly. Especially if the request is sensitive, it’s better to be safe than sorry and contact the supposed sender – if he or she isn’t a complete stranger (in which case, it goes without saying that it’s better to move on and ignore or even delete the SMS); preferably using an alternative channel to ensure that the request is indeed legitimate (by email, for example, or in person if possible).

- The pretext (and beyond that the action requested): is the request sensitive – could it have security repercussions? For example, am I being asked to connect somewhere by following a given link, or am I being asked to download a file onto my computer? What psychological tricks are being used to encourage me to take action? Is there a sense of urgency? But be careful! I’m not saying that a sensitive request necessarily indicates an attempt of *-ishing, but that we need to be vigilant whenever we are asked to take a sensitive action by SMS, email, telephone or other means.

- The link (or links): whether it appears to point to an internal site (spoofing a company domain) or to an external site (for example Gandi or OVH webmail), you need to take a little time to consider whether the domain name (the famous “TLD + 1”) is legitimate or not. Keeping in mind the common tricks (typosquatting, combosquatting, changing the TLD, etc.) used by attackers can certainly be useful, but the best reflex is undoubtedly not to follow a link received by SMS (email or other) and to prefer to use your browser’s favourites (you still need to have some for common applications). Another good reflex to adopt, for example before entering your login details somewhere, is always to check in the navigation bar the address of the application to which the link has redirected you after clicking – the best thing to do is not to click of course, but if you do click, it’s not (yet) too late as long as the login form has not been sent. Differences (more or less subtle) in the interface can (and should) also give cause for concern. For the record, we sometimes disable certain buttons on the interface to force a particular action.

To err is human, and all it takes for the attack to succeed is for the pretext to resonate with what the recipient expects or is in the process of doing. You may not believe me, but anyone can be fooled, and I would go even further: adopting this mindset is one of the surest ways of remaining vigilant and not erring on the side of overconfidence. In any case, you also need to make your employees aware of the right reflexes to adopt in the event of an attack:

- Communication is key. In the event of an attack, warning colleagues, for example, so that they don’t get trapped, can make all the difference. For the record, during a phishing campaign, one of our customers told us that warnings were exchanged internally on Slack just a few minutes after the emails had been sent. Excellent reflex! It goes without saying that for this to work, you need to have communication tools in place and your staff need to be used to using them.

- Communication during the attack is important, but communication after the attack is at least as important. For example, if an employee enters their login details where they shouldn’t have (although you still need to know this), you need to react as quickly as possible to prevent the compromise from spreading. Revoking the compromised session (by logging out) and changing the password are good reflexes, as is notifying the technical department so that they can investigate. In all cases, doing nothing gives the attacker an advantage. Once again, for this to work, there needs to be a culture of benevolence so as not to stigmatise employees. Anyone can be fooled (and statistically some attacks will succeed, so be prepared).

Anti-phishing technical measures

Now that we’ve looked at awareness-raising measures for employees, let’s move on to technical measures to reduce the risk of smishing:

- Implement 2 factor authentication for sensitive applications. Although certain techniques can be used to bypass it (man in the middle phishing, for example), securing authentication with a second factor remains an essential step. If the attacker gets hold of credentials – by whatever means (clone phishing, data leakage, purchase on the dark web, for example) – the password alone will not suffice in the presence of 2 factor authentication.

- Using a password manager (such as 1Password, KeePass, etc.) will enable you to have strong, unique passwords for each platform. In addition to robustness, the non-reuse of passwords is important, because otherwise, if an attacker recovers a password (valid on any site), he can potentially use it to compromise several accounts (on completely different sites). The ability to associate the generated identifiers also indirectly enables fraudulent sites to be detected, as shown in the following screenshot, where the (test) identifier is proposed by the password manager browser extension on the legitimate site (left), but not on the malicious site (right):

As you can see, the password manager also supports multi-factor authentication (the 2FA code will be generated by 1Password in this case). To talk more specifically about smishing, setting up a password manager on a mobile phone depends on the access you want. It may be preferable for certain applications to be accessible only from a computer.

The distinction between business and personal phones must also be taken into account. It is undesirable for passwords to sensitive applications to be stored on a personal device, which is undoubtedly less secure than a business device.

In conclusion, there are a number of good habits that all employees should adopt in a climate of goodwill. At the same time, technical measures can be taken to limit the risk of smishing and phishing in general.

Author: Benjamin BOUILHAC – Pentester @Vaadata

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh